External Development Finance Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accessbank Template CI Conform W/O Content

Offgrid Power Forum / Intersolar 21 June 2016 AccessHolding: Basic Facts German stock corporation (AG) created in 2006 Purpose: setting up small business banks in emerging markets „House Bank“ for MSME and low/middle-income households Full range of financial services but focus on business lending: Commercial bank license Core product: cash flow based lending to micro and small businesses Holding approach: Developing centralized core bank holding functions to support the emerging network Strategic Investor: AccessHolding aims to acquire majority stake Regional Clusters Responsible banking Commercial targets but long-term investment horizon: break-even in Y3-4; RoE of > 20% from Y5 on 27-Jun-16 #2 KPIs per December 2015 Paid-up capital of EUR 87.2 million Currently 10 financial institutions 8 banks & 2 MFOs 9 majority - owned Expansion plan for 14 institutions until 2021 Total Assets: EUR 1.2bn, Gross Loan Portfolio: EUR 0.9bn 570 thousand loans outstanding (95% for small business purpose) Average outstanding loan balance EUR 1,598 56% of the loan clients live in rural areas, usually with bad or no energy supply ~ 8,000 employees in 191 branches Two in three branches are located in rural areas 27-Jun-16 #3 History of Network Development Acquisition of AB Azerbaijan AB Tanzania AB Liberia AB Zambia MFO CREDO AH Share 16.5% AH Share 50.7% AH Share 55.6% AH Share 51.0% AH Share 60.2% Fitch Rating: BBB- Oct. 2002 Nov. 2007 Jan. 2009 Oct. 2011 Oct. 2014 Feb. 2007 Nov. 2008 Apr. 2010 Dec. 2013 Jan. 2015 Acquisition of AB Madagascar AB Nigeria -

Rwanda Economic Update

Public DisclosureRwand aAuthorized's Financial Sector AssePublicts, Rw Disclosuref billion Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 2 1 1 , , , 0 5 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 6 The Role of a Deeper and More Diversified Financial Sector Financing Development 2 0 June 2015|EditionNo.8 1 3 $41 1960 G D P p e 97842-RW r 2000 C $207 a p i t a 2013 $639 Rwanda Economic Update Financing Development The Role of a Deeper and More Diversified Financial Sector TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... i Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................ ii Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................ iv Part 1: Recent Economic Developments and Prospects ............................................................................................ 1 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2. Real Sector ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. External Sector .................................................................................................................................................. -

Career Opportunity

CAREER OPPORTUNITY AB Bank Rwanda Limited has been operating in Rwanda since January 2014. It is a member of an international network of commercial banks providing banking services to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises and private individuals in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Since the start of operations, AB Bank Rwanda has been growing remarkably in number of clients and staff. To further facilitate the growth of our client base and branch network we are now seeking motivated professionals to join us. With this in mind, applicants will need to demonstrate willingness to: • Find solutions for challenges in a changing market and work environment • Contribute to the growth of the bank • Understanding excellent customer service We are now seeking staff for the following position: I Job Description Overall Job Function Bring institution’s information security risks under explicit management control through the establishment and implementation of the Information Security Management System (ISMS). JOB TITLE: INFORMATION SECURITY OFFICER (ISO) LOCATION: KIGALI, RWANDA DEPARTMENT: IT START DATE: DD/MM/201Y POSITION HELD BY: FIRST NAME, SECOND NAME SUPERVISES: NONE AB INFORMATION SECURITY COMMITTEE & AH REPORTS TO: DEPUTIZED BY: NONE INFORMATION SECURITY MANAGER Key Responsibilities People Competencies • • Ability to communicate effectively with colleagues in various business project plan within given time- and budget limits; disciplines and IT regarding technical and business banking issues in English • Leading of formal approval process -

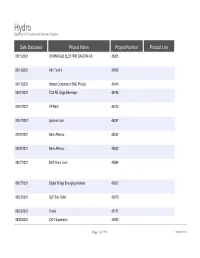

Date Disclosed Project Name Project Number Product Line 09/15/2021 OSMANGAZI ELEKTRIK DAGITIM AS 45265

Hydro Based on IFC Investment Services Projects Date Disclosed Project Name Project Number Product Line 09/15/2021 OSMANGAZI ELEKTRIK DAGITIM AS 45265 09/13/2021 A91 Fund II 45858 09/13/2021 Khaadi Corporation SMC Pvt Ltd 45445 09/07/2021 FCS RE Kings Beverage 44796 09/07/2021 AP Bank 45736 09/07/2021 Ipoteka Loan 45287 09/02/2021 Bank Alliance 45832 09/02/2021 Bank Alliance 45832 08/27/2021 BOP Omni Loan 43584 08/27/2021 Digital Bridge Emerging Markets 45362 08/23/2021 GyT Sub. Debt 43670 08/23/2021 Toters 45171 08/20/2021 CIDT Expansion 45030 Page 1 of 1790 09/24/2021 Hydro Based on IFC Investment Services Projects Company Name Country Sector OSMANGAZI ELEKTRIK Turkey Infrastructure DAGITIM AS A91 EMERGING FUND II India Funds LLP KHAADI SMC PVT. LTD. Pakistan Tourism, Retail, and Property KINGS BEVERAGES PVT Sierra Leone Agribusiness and Forestry LIMITED AGROPROSPERIS BANK, Ukraine Financial Institutions PAT IPOTEKA BANK JSC Uzbekistan Financial Institutions MORTGAGE BANK BANK ALLIANCE PUBLIC Ukraine Financial Institutions JOINT STOCK COMPANY BANK ALLIANCE PUBLIC Ukraine Financial Institutions JOINT STOCK COMPANY Omni S.A Credito Brazil Financial Institutions Financiamento e Investimento DIGITAL COLONY Latin America Region Telecommunications, Media, and Technology ACQUISITIONS BANCO G AND T Guatemala Financial Institutions CONTINENTAL S.A. TAN HOLDING SAL Lebanon Tourism, Retail, and Property COMPAGNIE IVOIRIENNE Cote D'Ivoire Agribusiness and Forestry Page 2 of 1790 09/24/2021 Hydro Based on IFC Investment Services Projects Environmental -

Capacity Building It’S in Our DNA Capacity Building – It’S in Our DNA

Capacity Building It’s In Our DNA Capacity Building – It’s In Our DNA Capacity Building – It’s In Our DNA Promoting local bank staff, and training them for their new roles, has always been part of our DNA in the AccessGroup. From our early days, in markets as diverse as Azerbaijan and Mozambique, we have always prioritised internal promotion over external recruitment. In doing this, we have always believed in the power of training to bring talented local staff to the competence levels demanded by their new roles. Initially, this capacity building was conducted locally by each network financial in- stitution’s (NFI’s) learning and development function. However, we soon found that we needed a more formal, standardised approach to ensure quality and network- wide consistency. Consequently, in May 2014, we inaugurated AccessCampus, our learning centre in Berlin. ACCESSCAMPUS Despite its success in providing capacities, skills and self-confidence to our middle and upcoming AccessCampus is a dynamic, flexible learning senior managers across the network, we were and development programme, held in three faced with two challenges. Firstly, we saw that blocks of two weeks over 18 months, aimed at while we have been able to capacitate middle our network’s future leaders. Its curriculum is management, the NFIs also had real capacity adjusted regularly to reflect the changing needs building needs at lower levels. Secondly, this of our NFIs and market requirements. Its stand- also became evident in the declining qualifica- ardised approach means we can guarantee that tions of candidates for AccessCampus. future leaders in every bank receive the same high-quality training experience. -

Regmifa Annual Rapport 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 REGIONAL MSME INVESTMENT FUND FOR SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA S.A., SICAV-SIF 2 REGMIFA TABLE OF CONTENTS 07 23 GREETINGS PERFORMANCE Letter from the Chairman Development Impact and Social Performance 09 25 Letter from the Investment Manager Outreach to End-Borrowers 27 13 Portfolio Environmental and Social STRATEGY Responsibility Rating 2016 Fund and Fund Structure 29 15 Fund Investment and Partner Lending Technical Assistance Facility Institution Development 37 Technical Assistance Facility 19 OVERVIEW 2016 Highlights 43 20 AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Market Overview and Outlook 77 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Organizational Structure and Investment Manager 79 Governance and Contacts 82 Abbreviations 3 REGMIFA ABOUT REGMIFA REGMIFA’s mission is to foster economic development in AS OF DECEMBER 2016 sub-Saharan Africa by supporting financial institutions that serve micro, small and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs) while simultaneously observing the principles of additionality GROSS ASSET VALUE and sustainability. USD 133.7 MILLION Launched in May 2010, the Regional MSME Investment Fund for sub-Saharan Africa SA, SICAV-SIF, is a Luxembourg-based investment fund that seeks to foster economic development and prosperity in sub-Saharan Africa. To this end, the Fund NET ASSET VALUE provides medium- to long-term debt financing in local currency to Partner Lending Institutions (PLIs) that serve MSMEs. USD 118.9 MILLION Complementary to the Fund’s investment activities, a specific Technical Assistance (TA) Facility focuses on providing technical support to client institutions. It was set up as an OUTSTANDING PORTFOLIO entity independent from the Fund and structured as a fiduciary (NOMINAL AT DISBURSEMENT) agreement under Luxembourg law in July 2010. -

Brd Annual Report 2020

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPOSITIONING FOR GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPANY OVERVIEW 04 FOREWORD Chairman Board of Directors’ statement 06 Chief Executive Officer’s report 08 GOVERNANCE OVERVIEW 12 Statement on Corporate Governance 12 Board and Executive Committee profiles 17 INSTITUTIONAL PERFORMANCE REVIEW 25 Financial performance Review 26 Operational performance report 28 Impact and sustainability highlights 31 Corporate Social Responsibility highlights 34 Stakeholder engagement highlights 35 BRD’s Outlook: Fitch Rating: B+/Stable 38 Risk Management Report 40 Strategy insights and outlook 42 Our Partners 48 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR 50 ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 Directors’ Report 54 INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Independent Auditor’s Report 59 Financial statements 64 REPOSITIONING FOR GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY 3 COMPANY OVERVIEW The Development Bank of Rwanda (BRD) Plc is Rwanda’s only national Development Finance Institution with the mandate to support the development of the private sector with a focus on priority sectors aligned to the national strategic goals. The Bank which marked 53 years in existence this year, has contributed to the country’s economic growth through financial and non-financial investments in key growth areas and progressively realigns itself to ensure relevance, competitiveness, and sustainability of its operations. The Bank offers short, medium- and long-term financing to small, medium, and large enterprises at attractive rates. OUR OUR VISION MISSION To be an innovative and A trusted strategic partner sustainable provider of for Rwanda’s development development finance for that offers financial socio-economic impact solutions for enhanced value to our stakeholders. OUR STRATEGIC THEMES OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS Continuous improvement Forming strategic of our credit and risk partnerships to deliver our management system, financial mandate is a key component performance and customer of our core activities. -

The Marketplace for Nutritious Foods: Rwanda Landscape Report

Commissioned by GAIN THE MARKETPLACE FOR NUTRITIOUS FOODS RWANDA LANDSCAPE REPORT Conducted By: Elizabeth Rogers Consulting Updated: March 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES & TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................................................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 6 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 2. UNDERSTANDING THE BURDEN OF MALNUTRITION: NUTRITION SITUATION ................................... 10 2.1 FOOD SECURITY ................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 STUNTING -

Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Annual Report Fy 2020

RWANDA NGURIZA NSHORE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2020 October 1, 2019 – September 30, 2020 Project Period of Performance: April 2018 - 2023 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content discussed is the sole responsibility of DAI and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. Program Title: Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID Rwanda Contract Number: 72069618C00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Contracting Officer Rep.: Fina Kayisanabo Activity Manager: Nadine Manzi, interim acting Chief of Party Date of Publication: October 30, 2020 Author: The Nguriza Nshore Team This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content discussed is the sole responsibility of DAI and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Activity Objectives ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Component I: Expand the Capacity of FIs and NBFIs to Finance SMEs and Agribusinesses ............... 4 Component 2: Increase private and commercial investment into SMEs and agribusinesses ............... 6 Component 3: Strengthen the policy environment -

Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Annual Report Fy19

RWANDA NGURIZA NSHORE ANNUAL REPORT FY19 October 1, 2018 – September 30, 2019 Project Period of Performance: April 2018 - 2023 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content discussed is the sole responsibility of DAI and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. ANNUAL REPORT YEAR 2, FISCAL YEAR 2019 (OCTOBER 1, 2018 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2019) Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Program Title: Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID Rwanda Contract Number: 72069618C00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Contracting Officer Rep.: Clementine Mukeka Activity Manager: Mark Rostal Date of Publication: October 30, 2019 Author: The Nguriza Nshore Team This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content discussed is the sole responsibility of DAI and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government RWANDA NGURIZA NSHORE | ANNUAL REPORT FY 2019 feedthefuture.gov CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... i EVALUATION OF PROGRAM AREAS ........................................................................................................... 1 ACTIVITY OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................. -

Ifc Mobile Money Scoping Country Report: Rwanda

IFC MOBILE MONEY SCOPING COUNTRY REPORT: RWANDA Margarete Biallas (with assistance from Alana Fook) RWANDA SUMMARY CURRENT MOBILE MONEY SOLUTIONSCurrently 6 mobile money solutions offered; 3 MNO offerings (largest), 3 Bank offerings. POPULATION 12.98 million MOBILE PENETRATION 9 million mobile subscribers (80% penetration according to RURA) FINANCIALLY INCLUDED POPULATION 38% through financial institutions, 42% overall, 18% through mobile accounts [Source: World Bank FINDEX] PERCENT UNDER POVERTY LINE 39.1% (2015) [Source: CIA] ECONOMICALLY ACTIVE POPULATION Labour force: 5.9 million (2015) [Source: CIA] ADULT LITERACY 70.5% (2015) [Source: CIA] MOBILE NETWORK OPERATORS MTN 34% market share Tigo 31% market share Airtel 20% market share KT Rwanda Networks 6% market share OVERALL READINESS RANKING 3 (moderate) Market Readiness Rwanda’s regulation and policies promote digital financial Regulation 4 services and discourage the use of cash. Financial inclusion in the country has shown significant Financial Sector 2 improvement in the last 4 years, primarily because of Telecom Sector 4 mobile money. However, the financial sector currently Distribution 3 does not offer competitive agent banking solutions. Market participants all agree that strong customer Market Demand 3 education and marketing is required. Macro-economic Overview Regulations Financial Sector Telecom Sector Other Sectors Digital Financial Services Landscape MOBILE BANKING MARKET POTENTIAL Key Country Statistics Insights ▪ Population: 12.98 million1 ▪ Two-thirds of the adult population -

RWANDA BANKING and INVESTMENT ANALYSIS Fueling Enterprise Innovation, Growth and Job Creation

RWANDA BANKING AND INVESTMENT ANALYSIS Fueling Enterprise Innovation, Growth and Job Creation This publication was produced by the USAID Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Project under Contract No. 720-696-18-C00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. RWANDA BANKING AND INVESTMENT ANALYSIS Fueling Enterprise Innovation, Growth and Job Creation Program Title: USAID Nguriza Nshore Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID Rwanda Contract Number: 720-696-18-C00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: September 10, 2018 Authors: Colleen Green and Robin Young Other contributors: Michael Baingana, Nadine Umuyana, Travis Massar and Guthrie Renwick This publication was produced by the USAID Rwanda Nguriza Nshore Project under Contract No. 720-696-18-C00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 UNDER COMPONENT 3: 3 INTRODUCTION 4 BACKGROUND ON NGURIZA NSHORE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE ANALYSIS 5 METHODOLOGY