The Minimalist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Threats of Partisanship to Minnesota's Judicial Elections George W

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 | Issue 2 Article 9 2008 The Threats of Partisanship to Minnesota's Judicial Elections George W. Soule Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Soule, George W. (2008) "The Threats of Partisanship to Minnesota's Judicial Elections," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 2, Article 9. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Soule: The Threats of Partisanship to Minnesota's Judicial Elections 8. SOULE - ADC.DOC 2/3/2008 3:54:10 PM THE THREATS OF PARTISANSHIP TO MINNESOTA’S JUDICIAL ELECTIONS George W. Soule† I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................702 II. THE FOUNDATION OF MINNESOTA’S JUDICIAL SELECTION SYSTEM ...................................................................................702 III. THE MODERN JUDICIAL SELECTION SYSTEM..........................704 A. Growth of the Minnesota Judiciary ..................................... 704 B. Minnesota Commission on Judicial Selection ...................... 705 C. Judicial Elections............................................................... 707 D. The Model of Non-Partisanship -

Application for the Position Member

Application for the position Member Part I: Position Sought Agency Name: Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board Position: Member Part II: Applicant Information Name: George William Soule Phone: (612) 251-5518 County: Hennepin Mn House District: 61B US House District: 5 Recommended by the Appointing Authority: True Part III: Appending Documentation Cover Letter and Resume Type File Type Cover Letter application/pdf Resume application/pdf Additional Documents (.doc, .docx, .pdf, .txt) Type File Name No additional documents found. Veteran: No Answer Part V: Signature Signature: George W. Soule Date: 2/15/2021 2:08:59 PM Page 1 of 1 February 2021 GEORGE W. SOULE Office Address: Home Address: Soule & Stull LLC 4241 E. Lake Harriet Pkwy. Eight West 43rd Street, Suite 200 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Work: (612) 353-6491 Cell: (612) 251-5518 E-mail: [email protected] LEGAL EXPERIENCE SOULE & STULL LLC, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 2014- BOWMAN AND BROOKE LLP, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 1985-2014 Managing Partner (Minneapolis office), 1996-1998, 2002-2004, 2007-10 TRIBAL COURT JUDGE White Earth Court of Appeals, 2012 - Prairie Island Indian Community Court of Appeals, 2016 - Fond du Lac Band Court of Appeals, 2017- Lower Sioux Indian Community, 2017 - GRAY, PLANT, MOOTY, MOOTY & BENNETT, Minneapolis, Minnesota Associate, Litigation Department, 1979-1985 Admitted to practice before Minnesota courts, 1979, Wisconsin courts, 1985, United States -

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: the Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: The Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court Rebecca Sherman Submitted to Professor Penny A. Hazelton to fulfill course requirements for Current Issues in Law Librarianship, LIS 595, and to fulfill the graduation requirement of the Culminating Experience Project for MLIS University of Washington Information School Seattle, Washington May 13, 2013 I. INTRODUCTION It has been twenty years since researches gave up the right to patent the World Wide Web and made the source code publicly available.1 Since entering the public domain, the web has revolutionized the way people get information. Although electronic databases such as Westlaw and Lexis have been around since the 70s, they have been transformed to keep pace with developments on the web. Google searching has become so popular that electronic databases are now being redesigned to emulate Google.2 Consider the Google-like search boxes in WestlawNext and Lexis Advance. As a result of the web and increasingly sophisticated databases, attorneys today no longer need to sift through heaps of books at the library. They have virtual access to information anytime and anywhere. Law is a profession that is highly dependent on information. The medium through which information is conveyed undoubtedly has effects on the way the law is understood. Where legal information once existed in a self-contained domain, today it can be found online amidst a universe of information.3 This change of access has raised some concerns. Professor Ellie -

Get Document

State of Minnesota Canvassing Report Report of the Votes Cast for Federal Partisan Offices, State Partisan Offices, and State Judicial Offices At the State General Election held Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Compiled from the Statements of the County Canvassing Boards and Incorporating the Changes to the Votes Counted For Candidates for Offices Reviewed at the 2010 Post Election Review Held in All the Counties of Minnesota Minnesota State Canvassing Report State General Election Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Minnesota Voter Statistics County Registered as of Registered on Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Total Voting 7am Election Day Regular Federal Only Presidential AITKIN 10,160 517 644 3 0 7,425 ANOKA 193,058 12,434 5,848 45 0 131,703 BECKER 18,865 941 938 0 0 11,904 BELTRAMI 24,832 1,982 1,028 4 0 16,187 BENTON 20,987 1,658 572 0 0 13,827 BIG STONE 3,594 98 159 2 0 2,233 BLUE EARTH 38,456 3,315 1,137 2 0 22,565 BROWN 14,706 1,092 586 1 0 10,517 CARLTON 19,785 1,110 725 4 0 13,780 CARVER 53,165 3,607 1,943 1 0 37,198 CASS 17,978 950 1,170 1 0 13,081 CHIPPEWA 7,164 393 272 0 0 4,905 CHISAGO 31,252 2,283 1,175 2 0 22,990 CLAY 31,100 2,530 1,082 3 0 19,273 CLEARWATER 4,779 336 231 0 0 3,590 COOK 3,467 156 275 2 0 2,858 COTTONWOOD 6,469 410 262 0 0 4,657 CROW WING 38,079 2,580 2,367 15 0 27,658 DAKOTA 237,746 16,316 10,426 28 0 162,919 DODGE 10,906 967 284 1 0 7,988 DOUGLAS 23,234 1,149 1,306 0 0 15,669 11/22/2010 7:44:33 AM Page 1 of 172 FARIBAULT 8,860 533 369 1 0 6,595 FILLMORE 12,757 869 352 0 0 8,466 FREEBORN 18,716 1,003 -

SUPREME COURT CALENDAR February 2021

STATE OF MINNESOTA IN SUPREME COURT SUPREME COURT CALENDAR February 2021 Please note the following time allotments for oral argument unless otherwise ordered by the Court: appellants are limited to 35 minutes and respondents are limited to 25 minutes. COURT CONVENES AT 9:00 A.M. (unless otherwise noted) Attorneys who will be arguing cases scheduled on this calendar should complete and return the argument appearance form attached at the end of this calendar. Attorneys in all cases scheduled for oral argument must check in with the Marshal in the courtroom to which the case is assigned (Capitol or Judicial Center), or virtual, if applicable, no later than 8:40 a.m. Counsel should be present and be prepared to begin whenever their case is called. Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea Justice G. Barry Anderson Justice Natalie E. Hudson Justice Margaret H. Chutich Justice Anne K. McKeig Justice Paul C. Thissen Justice Gordon L. Moore, III 2 En Banc Oral Case Number Date Location In re Petition for Disciplinary Action against A19-1461 2/03/21 Judicial Center, Barry L. Blomquist (Virtual) Roach, et al. v. Alinder, et al., Gary A19-2083 2/02/21 Judicial Center, Heitkamp Construction (Virtual) State v. Boss A19-1671 2/03/21 Judicial Center, (Virtual) State v. Friese A19-0451 2/01/21 Judicial Center, (Virtual) State v. Khalil A19-1281 2/04/21 Judicial Center, (Virtual) State v. McCoy A20-0485 2/02/21 Judicial Center, (Virtual) State v. Montano A20-0756 2/01/21 Judicial Center, (Virtual) 3 MINNESOTA JUDICIAL CENTER Monday, February 1, 2021 En Banc Oral State of Minnesota, Keith Ellison Respondent, Minnesota Attorney General Saint Paul, Minnesota Mark A. -

Introduction

Law Raza Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 3 2010 Introduction Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawraza Recommended Citation (2010) "Introduction," Law Raza: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawraza/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Raza by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law VOLUME 1 Spring 2010 P ART 1 The William Mitchell Law Raza Journal Founding Editor-in-Chief PABLO SARTORIO Editor-in-Chief DUCHESS HARRIS Faculty Advisor J. DAVID PRINCE Advisory Board Editors HON . PAUL ANDERSON NATALIA DARANCOU WILLOW ANDERSON CRAIG GREEN TAMARA CABAN -RAMIREZ GRETA E. HANSON SAM HANSON ANDREW T. POOLE HON . HELEN MEYER SIOBHAN TOLAR HON . ELENA OSTBY ROBERT T. TROUSDALE PETER REYES MAJ . PETER SWANSON HON . EDWARD TOUSSAINT JR. THE WILLIAM MITCHELL LAW RAZA JOURNAL VOLUME 1 Spring 2010 P ART 1 INTRODUCTION In his seminal essay, “Nuestra America” (“Our America”), the 19th century Cuban writer and revolutionary Jose Marti issued a clarion call to the people of Central and South America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean: Lo que quede de aldea en América ha de despertar. Estos tiempos no son para acostarse con el pañuelo en la cabeza, sino con las armas en la almohada… las armas del juicio, que vencen a las otras. Trincheras de ideas valen más que trincheras de piedra…. -

103 Editions Produced to Date

149 editions produced to date (revised 9-11-07) (1) Juvenile Court Hon. Robert Blaeser, Presiding Judge, Juvenile Court Hon. Denise Reily, Judge, Hennepin County Juvenile Court (taped 12-14-00) (2) Family Court Hon. Charles A. Porter, Jr., Presiding Judge, Hennepin County Family Court Hon. Diana Eagon, Judge, Hennepin County District Court (taped 12-14-00) (3) A Citizen's View of the Courts Bob Lurtsema, former Minnesota Viking Mark S. Thompson, Judicial District Administrator, Hennepin County District Court (taped 1-18-01) (4) JUSTice FOR KIDS / State Wards Advocacy Project Hon. Lucy Wieland, Assistant Chief Judge, Hennepin County District Court Lori A. Wagner, Esq., Faegre & Benson law firm Dianne C. Heins, Esq., Faegre & Benson law firm (taped 1-18-01) (5) Community Court Hon. Richard Hopper, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Elisabeth Steinberg, Project Coordinator, Hennepin County Community Court (taped 1-18-01) (6) Race, civil rights and the justice system - Part One Hon. Walter F. Mondale, former Vice President of the United States Hon. Tanya Bransford, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Leonardo Castro, Hennepin County Public Defender (taped 2-22-01) (7) Race, civil rights and the justice system- Part Two Hon. Tanya Bransford, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Leonardo Castro, Hennepin County Public Defender (taped 2-22-01) (8) Juries Hon. Myron Greenberg, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Sue MacPherson, Esq., Senior Trial Consultant, National Jury Project (taped 2-22-01) (9) DWI Hon. Stephen Swanson, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Sharon K. Gehrman-Driscoll, Director and Victim Advocate, Minnesotans for Safe Driving Tony Kresser, Career Probation Officer, Hennepin County Department of Community Corrections (taped 2-22-01) (10) Drug Court Hon. -

Perspectives the MAGAZINE for the UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL PERSPECTIVES the MAGAZINE for the UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL

FALL 2013 NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE FALL 2013 FALL 421 Mondale Hall PAID 229 19th Avenue South TWIN CITIES, MN Minneapolis, MN 55455 PERMIT NO. 90155 Perspectives THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL PERSPECTIVES THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL LAW THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA FOR THE MAGAZINE PLEASE JOIN US AS WE CELEBRATE THE LAW SCHOOL AND ITS ALUMNI DURING A WEEKEND OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE ENTIRE LAW SCHOOL COMMUNITY. IN THIS ISSUE Law in Practice Course Gives 1Ls a Jump-Start Law School Celebrates 125 Years Theory in Practice: Steve Befort (’74) Alumni News, Profiles and Class Notes Pre-1959 1979 1994 2004 Spring Alumni Weekend is about returning FRIDAY, APRIL 25: to remember your years at the Law School All-Alumni Cocktail Reception and the friendships you built here. We SATURDAY, APRIL 26: encourage those of you with class reunions Alumni Breakfast, CLE, Career Workshop, in 2014 to honor your special milestone Pre-1964 Luncheon, and Individual Class Reunions by making an increased gift or pledge to EARTH, WIND the Law School this year. Special reunion events will be held for the classes of: 1964, 1969, 1974, 1979, 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004, and 2009 law.umn.edu & LAWYERS For additional information, or if you are interested in participating in the planning of your class reunion, please contact Dinah Zebot, Director of Alumni Relations & Annual Giving, at 612.626.8671 or [email protected] The Evolving Challenges of Environmental Law www.community.law.umn.edu/saw DEAN BOARD OF ADVISORS David Wippman James L. -

Unallotment Conflict in Minnesota 2009-2010

Unallotment Conflict in Minnesota 2009-2010 Peter S. Wattson Senate Counsel State of Minnesota June 3, 2010 Contents Page Introduction ...........................................................1 I. The Statute - Minn. Stat. § 16A.152, subd. 4 .................................1 II. Governor’s Actions of May 2009 ..........................................2 III. Allotment Reductions of July 2009 .........................................2 IV. The Complaint - Brayton v. Pawlenty, November 3, 2009 ......................3 V. The Decision - Brayton v. Pawlenty, May 5, 2010 .............................4 VI. Close of the 2010 Legislative Session .......................................6 VII. Impact of Brayton v. Pawlenty on the Legislative Process ......................7 i ii Introduction This paper summarizes the conflict that has played out over the last year between the Minnesota Legislature and the Governor concerning the power of the Governor to reduce spending to prevent a deficit without the approval of the Legislature. It discusses the statute that gives the Governor, acting through the Commissioner of Management and Budget, the authority to reduce spending allotments in order to prevent a deficit; the Governor’s actions at the close of the legislative session in May 2009; the allotment reductions of July 2009; one of the lawsuits that challenged two of those reductions; the Supreme Court decision of May 2010; and the impact of that decision on the close of the 2010 legislative session. I. The Statute - Minn. Stat. § 16A.152, subd. 4 What -

Pocket Edition 2019.Indd

Minnesota Legislative Manual Blue Book 2019-2020 Pocket Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS Minnesota Facts .......................................................................................................... 3 State Symbols .............................................................................................................. 4 State Historic Sites ...................................................................................................... 7 State Song ................................................................................................................... 8 State Parks ................................................................................................................... 9 National Parks ........................................................................................................... 10 Vital Statistics............................................................................................................ 11 Higher Education ...................................................................................................... 13 Civic Engagement ..................................................................................................... 14 Flag Etiquette ............................................................................................................ 15 Pledge of Allegiance .................................................................................................. 15 National Anthem ..................................................................................................... -

The Work of General Counsel

FALL 2008 IN THIS ISSUE Dean Wippman Installed • Lawyers in Love • Law School’s 120th Anniversary The Work of General Counsel Alumni report satisfaction in being part of a company’s development and success. DEAN ALUMNI BOARD David Wippman Term ending 2009 DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS James Bender (’81) Cynthia Huff Elizabeth Bransdorfer (’85) (Secretary) Judge Natalie Hudson (’82) SENIOR EDITOR Chuck Noerenberg (’82) Judith Oakes (’69) Corrine Charais Patricia O’Gorman (’71) DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Term ending 2010 AND ANNUAL GIVING Grant Aldonas (’79) Anita C. Foster Austin Anderson (’58) Justice Paul Anderson (’68) CONTRIBUTING WRITERS David Eldred (’02) Corrine Charais Dave Kettner (’98) Anita Foster Rebecca Egge Moos (’77) Karen Hansen Judge James Rosenbaum (’69) Katherine Hedin Rachna Sullivan (’96) Evan Johnson Frank Jossi Term ending 2011 Jeffrey P. Justman J. Charles Bruse (’71) John Karalis William Drake (’66) Elizabeth Larsen Joan Humes (’90) (President) Cathy Madison E. Richard Larson (’69) Scotty Mann Jeannine Lee (’81) Marc Peña Marshall Lichty (’02) Joy Petersen Thor Lundgren (’74) Pamela Tabar Judge Peter Michalski (’71) Fordam Wara (’03) COVER ILLUSTRATION Stephen Webster PHOTOGRAPHERS Rick Dublin Mike Ekern Jayme Halbritter Josh Kohanek Mike Minehart Tim Rummelhoff Cory Ryan DESIGNER Carr Creatives Perspectives is a general interest magazine published in the fall and spring of the academic year for the University of Minnesota Law School community of alumni, friends, and supporters. Letters to the editor or any other communication regarding content should be sent to Cynthia Huff ([email protected]), Director of Communications, University of Minnesota Law School, 229 19th Avenue South, N225, Minneapolis, MN 55455. -

Spring 2010 U.S

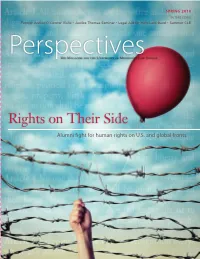

IN THIS ISSUE SPRING 2010 School w ota La ota nes Min of y sit ver Uni the for e Magazin The Alumni fight for human rights on U.S. and global fronts. Former Justice O’Connor Visits • Justice Thomas Seminar • Legal Aid for Mille Lacs Band • Summer CLE Rights on Their Side S P R I N G 2 0 1 0 Perspectives FORMER JUSTICE O’CONNOR VISITS • JUSTICE THOMAS SEMINAR• LEGAL AID FOR MILLE LACS BAND www.law.umn.edu PAID U.S. Postage Permit No. 155 Nonprofit Org. Minneapolis, MN N225 Mondale Hall 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Partners in Excellence Annual Fund Update Dear Friends and Fellow Alumni: As National Co-Chairs of this year’s Partners in DEAN LAW ALUMNI BOARD AND Excellence annual fund drive, we are pleased that many David Wippman BOARD OF VISITORS 2009-10 of you have chosen to benefit the Law School with Grant Aldonas (’79) your generosity through gifts to the Law School Fund. ASSISTANT DEAN AND Deborah Amberg (’90)† In this time of varied economic challenges, you have CHIEF OF STAFF Austin Anderson (’58) recognized the importance of contributing to the Law Nora Klaphake Justice Paul Anderson (’68) School, particularly in light of rapidly dwindling state Former Chief Justice support. We thank all of you who have given so far DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Russell Anderson (’68) and wish to specially acknowledge the generosity of Cynthia Huff Albert (Andy) Andrews (’66)† this year’s Fraser Scholars and Dean’s Circle donors James J. Bender (’81) (through April 15, 2010).