Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application for the Position Member

Application for the position Member Part I: Position Sought Agency Name: Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board Position: Member Part II: Applicant Information Name: George William Soule Phone: (612) 251-5518 County: Hennepin Mn House District: 61B US House District: 5 Recommended by the Appointing Authority: True Part III: Appending Documentation Cover Letter and Resume Type File Type Cover Letter application/pdf Resume application/pdf Additional Documents (.doc, .docx, .pdf, .txt) Type File Name No additional documents found. Veteran: No Answer Part V: Signature Signature: George W. Soule Date: 2/15/2021 2:08:59 PM Page 1 of 1 February 2021 GEORGE W. SOULE Office Address: Home Address: Soule & Stull LLC 4241 E. Lake Harriet Pkwy. Eight West 43rd Street, Suite 200 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 Work: (612) 353-6491 Cell: (612) 251-5518 E-mail: [email protected] LEGAL EXPERIENCE SOULE & STULL LLC, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 2014- BOWMAN AND BROOKE LLP, Minneapolis, Minnesota Founding Partner, Civil Trial Lawyer, 1985-2014 Managing Partner (Minneapolis office), 1996-1998, 2002-2004, 2007-10 TRIBAL COURT JUDGE White Earth Court of Appeals, 2012 - Prairie Island Indian Community Court of Appeals, 2016 - Fond du Lac Band Court of Appeals, 2017- Lower Sioux Indian Community, 2017 - GRAY, PLANT, MOOTY, MOOTY & BENNETT, Minneapolis, Minnesota Associate, Litigation Department, 1979-1985 Admitted to practice before Minnesota courts, 1979, Wisconsin courts, 1985, United States -

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: the Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court

Assessing the Changing Nature of Authority in the Web Age: The Citation Practices of Minnesota Supreme Court Rebecca Sherman Submitted to Professor Penny A. Hazelton to fulfill course requirements for Current Issues in Law Librarianship, LIS 595, and to fulfill the graduation requirement of the Culminating Experience Project for MLIS University of Washington Information School Seattle, Washington May 13, 2013 I. INTRODUCTION It has been twenty years since researches gave up the right to patent the World Wide Web and made the source code publicly available.1 Since entering the public domain, the web has revolutionized the way people get information. Although electronic databases such as Westlaw and Lexis have been around since the 70s, they have been transformed to keep pace with developments on the web. Google searching has become so popular that electronic databases are now being redesigned to emulate Google.2 Consider the Google-like search boxes in WestlawNext and Lexis Advance. As a result of the web and increasingly sophisticated databases, attorneys today no longer need to sift through heaps of books at the library. They have virtual access to information anytime and anywhere. Law is a profession that is highly dependent on information. The medium through which information is conveyed undoubtedly has effects on the way the law is understood. Where legal information once existed in a self-contained domain, today it can be found online amidst a universe of information.3 This change of access has raised some concerns. Professor Ellie -

Get Document

State of Minnesota Canvassing Report Report of the Votes Cast for Federal Partisan Offices, State Partisan Offices, and State Judicial Offices At the State General Election held Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Compiled from the Statements of the County Canvassing Boards and Incorporating the Changes to the Votes Counted For Candidates for Offices Reviewed at the 2010 Post Election Review Held in All the Counties of Minnesota Minnesota State Canvassing Report State General Election Tuesday, November 2, 2010 Minnesota Voter Statistics County Registered as of Registered on Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Absentee Ballots Total Voting 7am Election Day Regular Federal Only Presidential AITKIN 10,160 517 644 3 0 7,425 ANOKA 193,058 12,434 5,848 45 0 131,703 BECKER 18,865 941 938 0 0 11,904 BELTRAMI 24,832 1,982 1,028 4 0 16,187 BENTON 20,987 1,658 572 0 0 13,827 BIG STONE 3,594 98 159 2 0 2,233 BLUE EARTH 38,456 3,315 1,137 2 0 22,565 BROWN 14,706 1,092 586 1 0 10,517 CARLTON 19,785 1,110 725 4 0 13,780 CARVER 53,165 3,607 1,943 1 0 37,198 CASS 17,978 950 1,170 1 0 13,081 CHIPPEWA 7,164 393 272 0 0 4,905 CHISAGO 31,252 2,283 1,175 2 0 22,990 CLAY 31,100 2,530 1,082 3 0 19,273 CLEARWATER 4,779 336 231 0 0 3,590 COOK 3,467 156 275 2 0 2,858 COTTONWOOD 6,469 410 262 0 0 4,657 CROW WING 38,079 2,580 2,367 15 0 27,658 DAKOTA 237,746 16,316 10,426 28 0 162,919 DODGE 10,906 967 284 1 0 7,988 DOUGLAS 23,234 1,149 1,306 0 0 15,669 11/22/2010 7:44:33 AM Page 1 of 172 FARIBAULT 8,860 533 369 1 0 6,595 FILLMORE 12,757 869 352 0 0 8,466 FREEBORN 18,716 1,003 -

The Minimalist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court1

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 2 Article 10 2011 Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The inimM alist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court Carol Weissenborn Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Weissenborn, Carol (2011) "Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The inimM alist Architecture of the Minnesota Supreme Court," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 37: Iss. 2, Article 10. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Weissenborn: Rocks rather than Cathedrals: The Minimalist Architecture of the ROCKS RATHER THAN CATHEDRALS: THE MINIMALIST ARCHITECTURE OF THE MINNESOTA SUPREME COURT1 Carol Weissenborn† I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 883 II. BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 884 A. A Voting Bloc .................................................................... 884 B. A Distinct Philosophy ........................................................ 886 III. STATE V. PECK: WORDS AS ROCKS ........................................... 891 IV. BRAYTON V. PAWLENTY: REORDERING THE ROCKS .................. 896 -

103 Editions Produced to Date

149 editions produced to date (revised 9-11-07) (1) Juvenile Court Hon. Robert Blaeser, Presiding Judge, Juvenile Court Hon. Denise Reily, Judge, Hennepin County Juvenile Court (taped 12-14-00) (2) Family Court Hon. Charles A. Porter, Jr., Presiding Judge, Hennepin County Family Court Hon. Diana Eagon, Judge, Hennepin County District Court (taped 12-14-00) (3) A Citizen's View of the Courts Bob Lurtsema, former Minnesota Viking Mark S. Thompson, Judicial District Administrator, Hennepin County District Court (taped 1-18-01) (4) JUSTice FOR KIDS / State Wards Advocacy Project Hon. Lucy Wieland, Assistant Chief Judge, Hennepin County District Court Lori A. Wagner, Esq., Faegre & Benson law firm Dianne C. Heins, Esq., Faegre & Benson law firm (taped 1-18-01) (5) Community Court Hon. Richard Hopper, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Elisabeth Steinberg, Project Coordinator, Hennepin County Community Court (taped 1-18-01) (6) Race, civil rights and the justice system - Part One Hon. Walter F. Mondale, former Vice President of the United States Hon. Tanya Bransford, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Leonardo Castro, Hennepin County Public Defender (taped 2-22-01) (7) Race, civil rights and the justice system- Part Two Hon. Tanya Bransford, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Leonardo Castro, Hennepin County Public Defender (taped 2-22-01) (8) Juries Hon. Myron Greenberg, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Sue MacPherson, Esq., Senior Trial Consultant, National Jury Project (taped 2-22-01) (9) DWI Hon. Stephen Swanson, Judge, Hennepin County District Court Sharon K. Gehrman-Driscoll, Director and Victim Advocate, Minnesotans for Safe Driving Tony Kresser, Career Probation Officer, Hennepin County Department of Community Corrections (taped 2-22-01) (10) Drug Court Hon. -

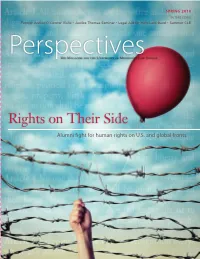

Perspectives the MAGAZINE for the UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL PERSPECTIVES the MAGAZINE for the UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL

FALL 2013 NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE FALL 2013 FALL 421 Mondale Hall PAID 229 19th Avenue South TWIN CITIES, MN Minneapolis, MN 55455 PERMIT NO. 90155 Perspectives THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL PERSPECTIVES THE MAGAZINE FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL LAW THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA FOR THE MAGAZINE PLEASE JOIN US AS WE CELEBRATE THE LAW SCHOOL AND ITS ALUMNI DURING A WEEKEND OF ACTIVITIES FOR THE ENTIRE LAW SCHOOL COMMUNITY. IN THIS ISSUE Law in Practice Course Gives 1Ls a Jump-Start Law School Celebrates 125 Years Theory in Practice: Steve Befort (’74) Alumni News, Profiles and Class Notes Pre-1959 1979 1994 2004 Spring Alumni Weekend is about returning FRIDAY, APRIL 25: to remember your years at the Law School All-Alumni Cocktail Reception and the friendships you built here. We SATURDAY, APRIL 26: encourage those of you with class reunions Alumni Breakfast, CLE, Career Workshop, in 2014 to honor your special milestone Pre-1964 Luncheon, and Individual Class Reunions by making an increased gift or pledge to EARTH, WIND the Law School this year. Special reunion events will be held for the classes of: 1964, 1969, 1974, 1979, 1984, 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004, and 2009 law.umn.edu & LAWYERS For additional information, or if you are interested in participating in the planning of your class reunion, please contact Dinah Zebot, Director of Alumni Relations & Annual Giving, at 612.626.8671 or [email protected] The Evolving Challenges of Environmental Law www.community.law.umn.edu/saw DEAN BOARD OF ADVISORS David Wippman James L. -

Unallotment Conflict in Minnesota 2009-2010

Unallotment Conflict in Minnesota 2009-2010 Peter S. Wattson Senate Counsel State of Minnesota June 3, 2010 Contents Page Introduction ...........................................................1 I. The Statute - Minn. Stat. § 16A.152, subd. 4 .................................1 II. Governor’s Actions of May 2009 ..........................................2 III. Allotment Reductions of July 2009 .........................................2 IV. The Complaint - Brayton v. Pawlenty, November 3, 2009 ......................3 V. The Decision - Brayton v. Pawlenty, May 5, 2010 .............................4 VI. Close of the 2010 Legislative Session .......................................6 VII. Impact of Brayton v. Pawlenty on the Legislative Process ......................7 i ii Introduction This paper summarizes the conflict that has played out over the last year between the Minnesota Legislature and the Governor concerning the power of the Governor to reduce spending to prevent a deficit without the approval of the Legislature. It discusses the statute that gives the Governor, acting through the Commissioner of Management and Budget, the authority to reduce spending allotments in order to prevent a deficit; the Governor’s actions at the close of the legislative session in May 2009; the allotment reductions of July 2009; one of the lawsuits that challenged two of those reductions; the Supreme Court decision of May 2010; and the impact of that decision on the close of the 2010 legislative session. I. The Statute - Minn. Stat. § 16A.152, subd. 4 What -

Pocket Edition 2019.Indd

Minnesota Legislative Manual Blue Book 2019-2020 Pocket Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS Minnesota Facts .......................................................................................................... 3 State Symbols .............................................................................................................. 4 State Historic Sites ...................................................................................................... 7 State Song ................................................................................................................... 8 State Parks ................................................................................................................... 9 National Parks ........................................................................................................... 10 Vital Statistics............................................................................................................ 11 Higher Education ...................................................................................................... 13 Civic Engagement ..................................................................................................... 14 Flag Etiquette ............................................................................................................ 15 Pledge of Allegiance .................................................................................................. 15 National Anthem ..................................................................................................... -

MJB Report to the Community 2012

Report to the Community The 2012 Annual Report of the Minnesota Judicial Branch Minnesota Judicial Branch • 25 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. • Saint Paul, MN 55155 Letter from the Chief Justice Dear fellow Minnesotans, I am pleased to present the 2012 Minnesota Judicial Branch Annual Report to the Community, which details the progress we have made on our ongoing efforts to improve the delivery of justice in our state. Over the past year we have continued to expand and improve our sharing of case information with our justice system partners, including beginning work on an updated system for timely sharing of court issued orders for protection with law enforcement agencies. By the end of 2012, the Judicial Branch was generating 1.4 million data exchanges per month with government agencies. The past year also saw the expansion of eFiling (electronic case initiation and updating) and eService. eFiling and eService for civil and family cases was made mandatory for attorneys and government agencies in district courts in Hennepin and Ramsey counties beginning September 1, 2012, and expanded on a voluntary basis to courts in Cass, Clay, Dakota, Faribault, Morrison and Washington counties. eFiling and eService is just one piece of our ambitious eCourtMN initiative, an effort to convert from paper to electronic court records. I am proud of the work our judges and employees did in 2012 to develop new and more effective ways to fulfill our mission of providing timely justice to the people of Minnesota, and I hope you find this report informative and useful. Sincerely, Lorie S. -

The Work of General Counsel

FALL 2008 IN THIS ISSUE Dean Wippman Installed • Lawyers in Love • Law School’s 120th Anniversary The Work of General Counsel Alumni report satisfaction in being part of a company’s development and success. DEAN ALUMNI BOARD David Wippman Term ending 2009 DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS James Bender (’81) Cynthia Huff Elizabeth Bransdorfer (’85) (Secretary) Judge Natalie Hudson (’82) SENIOR EDITOR Chuck Noerenberg (’82) Judith Oakes (’69) Corrine Charais Patricia O’Gorman (’71) DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS Term ending 2010 AND ANNUAL GIVING Grant Aldonas (’79) Anita C. Foster Austin Anderson (’58) Justice Paul Anderson (’68) CONTRIBUTING WRITERS David Eldred (’02) Corrine Charais Dave Kettner (’98) Anita Foster Rebecca Egge Moos (’77) Karen Hansen Judge James Rosenbaum (’69) Katherine Hedin Rachna Sullivan (’96) Evan Johnson Frank Jossi Term ending 2011 Jeffrey P. Justman J. Charles Bruse (’71) John Karalis William Drake (’66) Elizabeth Larsen Joan Humes (’90) (President) Cathy Madison E. Richard Larson (’69) Scotty Mann Jeannine Lee (’81) Marc Peña Marshall Lichty (’02) Joy Petersen Thor Lundgren (’74) Pamela Tabar Judge Peter Michalski (’71) Fordam Wara (’03) COVER ILLUSTRATION Stephen Webster PHOTOGRAPHERS Rick Dublin Mike Ekern Jayme Halbritter Josh Kohanek Mike Minehart Tim Rummelhoff Cory Ryan DESIGNER Carr Creatives Perspectives is a general interest magazine published in the fall and spring of the academic year for the University of Minnesota Law School community of alumni, friends, and supporters. Letters to the editor or any other communication regarding content should be sent to Cynthia Huff ([email protected]), Director of Communications, University of Minnesota Law School, 229 19th Avenue South, N225, Minneapolis, MN 55455. -

Spring 2010 U.S

IN THIS ISSUE SPRING 2010 School w ota La ota nes Min of y sit ver Uni the for e Magazin The Alumni fight for human rights on U.S. and global fronts. Former Justice O’Connor Visits • Justice Thomas Seminar • Legal Aid for Mille Lacs Band • Summer CLE Rights on Their Side S P R I N G 2 0 1 0 Perspectives FORMER JUSTICE O’CONNOR VISITS • JUSTICE THOMAS SEMINAR• LEGAL AID FOR MILLE LACS BAND www.law.umn.edu PAID U.S. Postage Permit No. 155 Nonprofit Org. Minneapolis, MN N225 Mondale Hall 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Partners in Excellence Annual Fund Update Dear Friends and Fellow Alumni: As National Co-Chairs of this year’s Partners in DEAN LAW ALUMNI BOARD AND Excellence annual fund drive, we are pleased that many David Wippman BOARD OF VISITORS 2009-10 of you have chosen to benefit the Law School with Grant Aldonas (’79) your generosity through gifts to the Law School Fund. ASSISTANT DEAN AND Deborah Amberg (’90)† In this time of varied economic challenges, you have CHIEF OF STAFF Austin Anderson (’58) recognized the importance of contributing to the Law Nora Klaphake Justice Paul Anderson (’68) School, particularly in light of rapidly dwindling state Former Chief Justice support. We thank all of you who have given so far DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Russell Anderson (’68) and wish to specially acknowledge the generosity of Cynthia Huff Albert (Andy) Andrews (’66)† this year’s Fraser Scholars and Dean’s Circle donors James J. Bender (’81) (through April 15, 2010). -

A Tribute to the Honorable Helen Meyer Eric S

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 39 | Issue 5 Article 11 2013 A Tribute to the Honorable Helen Meyer Eric S. Janus Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Janus, Eric S. (2013) "A Tribute to the Honorable Helen Meyer ," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 39: Iss. 5, Article 11. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol39/iss5/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Janus: A Tribute to the Honorable Helen Meyer A TRIBUTE TO THE HONORABLE HELEN MEYER † Eric S. Janus When Justice Helen Meyer stepped off the Minnesota Supreme Court last year, the court lost a distinctive and valuable voice. But her vision for our justice system and our society will continue. She leaves a legacy that will improve the lives of children for generations to come. Appointed to the supreme court by Governor Jesse Ventura in 2003, Helen Meyer brought a new perspective to that tribunal. As a trained social worker, she had worked with youth in locked psychiatric wards, seeing firsthand the effects of abuse, neglect, and chemical dependency, and the importance of appropriate interventions. Years later, Chief Justice Lorie Gildea would observe, “She worked with people who will never be in more need of the commitment and strength of a wise, resourceful advocate, and she answered that call.”1 But the social work role was not enough, so she turned to law.