Gorringesc2016outofthecheris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

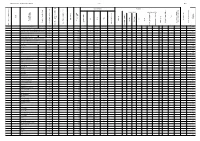

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Building Maintenance Sub Division No

Building Maintenance Sub Division No. I, Madurai. R.P.B. Page 1 . Nature of Elements Book Value Electrical Rs.(b) External Services Rs.(c) Etc., Total District Remarks area in Sq.m.area (Constructed by) (Constructed Wall Roof Floor Height of Storey of Height Occupying Department Occupying SubsidaryBuilding Lifts Dismenssion plinth Name of Building of Name / Roads Civil Rs. (A) (A) Rs. Civil A.C Units A.C Cold Storage Type Foundation of Survey No., DoorVillage No., Survey No., Head of Account under Account of Head which SCost of Subsquent of SCost Additions funds Allotted for Construction for funds Allotted Assessed Standard Rent FR 45 A/FR 45B FR45 Rent Standard Assessed Total Rs. [a+b+c] Rs. Total No. of Storeys Present / Ultiimate / Present Storeys of No. Year of Construction Acquistion / Year Windows And Ventilators Wiring Fixtures Fitting & Sl. No . of Building of . No Sl. Subsidary / Building Type Building of Framed / Load Bearing Electrical Including Electrical Transformers Water Supply Drainage Water Arrangements & 1 Madurai (North Sub Dn.) Bldgs.Mtce. 1017 / 2, 1021, 1022, 10231963 1 92.40 BW in CM Madras Terrace Cement floor PWD PWD Section Office (North Building of) (Bldgs. Mtce.Sub Dn.No.I, Madurai.) 1960 1 102.80 ..do.. AC Sheet --- ..do.. ..do.. Madurai Division Office (Buildings Maintenance Dn., Madurai 1971 1 469.00 ..do.. RCC --- ..do.. ..do.. (Spl. Bldgs.Circle) Bldgs. (M&C) Circle No.I, Madurai - 2.Office building 1974 1 455.00 ..do.. ..do.. --- ..do.. ..do.. Electrical Division Office Bldg. GF 1977 2 242.28 ..do.. ..do.. --- ..do.. ..do.. Buildings Maintenance Circle No.II, Madurai Office Building FF only 1 240.00 ..do. -

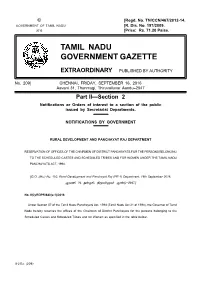

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price: Rs. 4.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 27] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JULY 11, 2012 Aani 27, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2043 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT CONTENTS Pages. Pages. COMMERCIAL TAXES AND REGISTRATION HOME DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT (S.C.) Tamil Nadu Value Added Tax Act—Appointment of Award of the Fire Service Medal for Meritorious Thiru K. Naganathan, Special Judge as the Service on the occasion of the Republic Chairman of the Tamil Nadu Sales Tax Appellate Day, 2012. .. .. .. .. 324 Tribunal, Chennai .. .. .. 316 Award of the President’s Police Medal for ENVIRONMENT AND FOREST DEPARTMENT Distinguished Service and Police Medal Notifications under the Tamil Nadu Forest Act— for Meritorious Service on the occasion of the Republic Day, 2012 .. .. Declaration of Forest Block as Reserved Forests 324-325 Appointment of Special Tahsildar as Settlement Officer District Forest Officer, HOME, PROHIBITION AND EXCISE Personal Assistant (General) to the Collectors DEPARTMENT of certain Districts .. .. .. 316-323 Amendments to Tamil Nadu Prohibition Act. 325-326 Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act— Nomination of certain person as an official member of Tamil Nadu Pollution Control ªî£Nô£÷˜ ñŸÁ‹ «õ¬ôõ£ŒŠ¹ˆ 323 ªî£Nô£÷˜ ñŸÁ‹ «õ¬ôõ£ŒŠ¹ˆ Board .. .. .. .. ¶¬ø HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Industrial Disputes Act—Disputes between Workmen and Managements referred to Bharathiar University Act.—Nomination of certain Labour Courts for Adjudication .. .. 326 persons as members to the syndicate of the Bharathiar University, Coimbatore for certain period . -

Reservations of Offices

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2016 [Price: Rs. 71.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 209] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2016 Aavani 31, Thunmugi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2047 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ DEPARTMENT RESERVATION OF OFFICES OF THE CHAIRMEN OF DISTRICT PANCHAYATS FOR THE PERSONS BELONGING TO THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES AND FOR WOMEN UNDER THE TAMIL NADU PANCHAYATS ACT, 1994. [G.O. (Ms.) No. 102, Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (PR-1) Department, 16th September 2016, ÝõE 31, ¶¡ºA, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´-2047.] No. II(2)/RDPR/640(a-1)/2016 Under Section 57 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act, 1994 (Tamil Nadu Act 21 of 1994), the Governor of Tamil Nadu hereby reserves the offices of the Chairmen of District Panchayats for the persons belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and for Women as specified in the table below:- II-2 Ex. (209) 2 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY THE TABLE RESERVATION OF OFFICES OF CHAIRMEN OF DISTRICT PANCHAYATS Sl. Category to which reservation is Name of the District No. made (1) (2) (3) 1 The Nilgiris ST General 2 Namakkal SC Women 3 Tiruppur SC Women 4 Virudhunagar SC Women 5 Tirunelveli SC Women 6 Thanjavur SC General 7 Ariyalur SC General 8 Dindigul SC General 9 Ramanathapuram SC General 10 Kancheepuram General Women 11 Tiruvannamalai -

Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU

pincode officename districtname statename 600001 Flower Bazaar S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Chennai G.P.O. Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Govt Stanley Hospital S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mannady S.O (Chennai) Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Sowcarpet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Anna Road H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Chintadripet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Madras Electricity System S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Park Town H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Edapalayam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Madras Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Ripon Buildings S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mandaveli S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Vivekananda College Madras S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mylapore H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Tiruvallikkeni S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Chepauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Madras University S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Parthasarathy Koil S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Greams Road S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 DPI S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Shastri Bhavan S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Teynampet West S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600007 Vepery S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Ethiraj Salai S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore ND S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600009 Fort St George S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur North S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Sembiam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600012 Perambur Barracks S.O Chennai -

District Profile 2014-15

DISTRICT PROFILE 2014-15 MADURAI DISTRICT OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS, MADURAI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 2014-15 Madurai Dist Tamilnadu 1. GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION 2014-15 2011 North Latitude between 9o30'00" and 10 o30'00" 8o5' and 13o35" 76o15' and East Longitude between 77o00'00" and 78o30'00" 80o20' 2. AREA and POPULATION 2011 Census 2011 Census i.Area in Square km. 3741.73 130058 ii.Population 3038252 72147030 (a) Males 1526475 36137975 (b) Females 1511777 36009055 (c) Rural 1191451 37229590 (d) Urban 1846801 34917440 iii.Density/Sq.km. 812 555 iv.Literates 2273430 40524545 a. Males (%) 89.72 86.77 b. Females (%) 77.16 73.14 v.Main Workers 1173902 27942181 a.Total Workers 1354632 32884681 b.Male Workers 902704 21434978 c.Female Workers 451928 11449703 d.Cultivators 81352 3855375 e.Agricultural Labourers 287731 7234101 f.Household Industry 39753 1119458 g. Other Workers 765066 15733247 h.MarginalWorkers 180730 4942500 vi.Non-Workers 1683620 39262349 vii.Language spoken in the District & Tamil,Telugu,Sourastra, English, State Hindi, Malayalam, Gujarathi 3. VITAL STATISTICS 2014-15 2012 i Births (Rural) 28483 ii Deaths (Rural) 11963 iii Infant Deaths (Rural) 416 iv Birth Rate (per1000population) (a) Rural 16.00 15.8 (b) Urban - 15.6 v Death Rate (per1000 population) (a) Rural 13.4 8.2 (b) Urban - 6.4 vi IMR (a) Rural 14.6 24 (b)Urban - 18 Madurai Dist Tamilnadu 2014-15 vii Expectation of life at birth 2011-15 (a) Male 68.70 68.60 (b) Female 71.54 71.80 No. of deaths of women due to Viii 23 problems related to child birth (a) At the time of delivery -- -- (b) During Pregnancy -- -- (c) After child birth (with in 42 days) -- -- 4 TEMPERATURE (IN CELCIOUS) 2012-13 a)Plains (2014-15) i. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Janarthanan, Dhivya (2019) The country near the city : social space and dominance in Tamil Nadu. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30970 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. The Country near the City: Social Space and Dominance in Tamil Nadu Dhivya Janarthanan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of Sociology and Anthropology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London ABSTRACT The Country near the City: Social Space and Dominance in Tamil Nadu Recent anthropological, geographical, and historical studies have exorcised the conceptualisation of space as an empty container. Yet the anthropology of space often limits itself to examining representations of space instead of comprehending the wider spectrum of relations and processes that produce social space itself. Within the field of South Asian ethnography, this has, combined with the rejection of the ‘legacies’ of village studies, cast a shadow over the village as an ontologically and epistemologically relevant category. -

Water Resources Atlas Madurai District

WATER RESOURCES ATLAS OF MADURAI DISTRICT (Sedapatti Block) Conceptualised & Edited by Dr. Chandra Mohan B. I.A.S District Collector Madurai Communication Cell District Rural Development Agency Madurai WATER RESOURCES ATLAS OF MADURAI DISTRICT CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION I 2. IRRIGATION OF TANKS AND PONDS IN TAMIL NADU I - III 2.1 Indigenous Water harvesting structure I 2.2 Declining Local Management II 2.3 Village Ponds and Ooranies II 2.4 Tanks becoming an Endangered species II 2.5 Reviving Tank Systems. III 3. PERSPECTIVE PLANNING FOR WATER RESOURCES DE- VELOPMENT III - V 3.1 Need for information Systems III 3.2 Need for basic data on Tanks and Ponds in each district III 3.3 Data Collection process and Block-wise compilation of data. III - IV 3.4 Salient Features of Madurai District V 4. NATURE OF DATA AVAILABLE IN THIS ATLAS V 5. PROFILE OF SEDAPATTI BLOCK VI 6. MADURAI DISTRICT PANCHAYAT UNIONS VII 7. sedapatti PANCHAYAT UNION VIII 8. SL. village NAMES No 1 Elumalai 1 - 32 2 Mellapuram 33 - 54 3 Soolapuram 55 - 72 4 Seelanaickanpatti 73 - 90 5 Peraiyampatti 91 - 104 6 Uthapuram 105 -124 7 E.Kottaipatti 125 - 136 8 MellaThirumanikam 137 - 146 9 Thirumanikam 147 - 160 10 Thadiyampatti 161 - 170 11 Manibamettupatti 171 - 174 12 Vannankulam 175 - 194 13 Athikaripatti 195 - 206 14 Periyakkattalai 207 - 214 15 Chinnakkattalai 215 - 220 16 Perungamanallur 221 - 234 17 Kallappanpatty 235 - 250 18 Poosalapuram 251 - 258 19 Sembarani 259 - 266 20 Kuppalnatham 267 - 280 21 Sedapatti 281 - 290 22 Avalaseri 291 - 298 23 Jambalapuram 299 - 308 24 Kathuvarpatti 309 - 318 25 Kudipatti 319 - 328 26 Pappinaickanpatti 329 - 346 27 Thulukkuttinaickanur 347 - 360 28 Vettilpatty 361 - 366 29 Vandari 367 - 374 30 Saptur 375 - 390 31 Athipatti 391 - 422 32 Kudiseri 423 - 444 33 Mangalarevu 445 - 456 34 Nagayapuram 457 - 458 WATER RESOURCES ATLAS OF MADURAI DISTRICT 1. -

List of Polling Stations for 197 Usilampatti Assembly Segment Within the 33 Theni Parliamentary Constituency

List of Polling Stations for 197 Usilampatti Assembly Segment within the 33 Theni Parliamentary Constituency Whether for All Polling Location and name of building in Voters or Men Sl.No Polling Areas station No. which Polling Station located only or Women only 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 Pt. Union Middle School, ,North 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Uthappanaickanur Ward 1 , All Voters facing, South west Building, 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS Uthappanaickanur-625537 2 2 Pt. Union Middle School, ,South 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Uthappanaickanur Ward 2 , All Voters Concrete Building 2.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Vadipatti Ward 1 , Uthappanaickanur-625537 3.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Uthappanaickanur , 4.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Usilampatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 3 3 Pt. Union Middle School, ,South 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Uthappanaickanur Ward 2 , All Voters West Terraced Building, 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS Uthappanaickanur - 625537 4 4 Pt. Union Middle School, ,East 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Maruthampatti Ward 1 , All Voters Side New Addl. 2.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Sakkiyar Street Ward 2 , Building,,Uthappanaickanur - 3.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Ayenkovilpatti Ward 3 , 625537 4.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Kulathupatti Ward 4 , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 5 5 Pt. Union Ele.School, ,Addl. 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur (P) Pudukkottai Ward 4 , All Voters R.C.C Building,Facing West 2.Uthappanaicanur (R.V)Uthappanaicanur(P) Kannimarpuram Ward 4 , U.Pudukottai - 625537 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 6 6 Pt.Union Ele.School ,Addl. 1.Uthappanaickanur (R.V) Uthappanaickanur(P) Mondikundu Ward 1 , All Voters R.C.C. -

District Profile 2015-16

DISTRICT PROFILE 2015-16 MADURAI DISTRICT OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS, MADURAI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 2015-16 Madurai Dist Tamilnadu 1. GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION 2015-16 2015-16 North Latitude between 9o30'00" and 10 o30'00" 8o5' and 13o35" 76o15' and East Longitude between 77o00'00" and 78o30'00" 80o20' 2. AREA and POPULATION 2011 Census 2011 Census i.Area in Square km. 3741.73 130058 ii.Population 3038252 72147030 (a) Males 1526475 36137975 (b) Females 1511777 36009055 (c) Rural 1191451 37229590 (d) Urban 1846801 34917440 iii.Density/Sq.km. 812 555 iv.Literates 2273430 40524545 a. Males (%) 89.72 86.77 b. Females (%) 77.16 73.14 v.Main Workers 1173902 27942181 a.Total Workers 1354632 32884681 b.Male Workers 902704 21434978 c.Female Workers 451928 11449703 d.Cultivators 81352 3855375 e.Agricultural Labourers 287731 7234101 f.Household Industry 39753 1119458 g. Other Workers 765066 15733247 h.MarginalWorkers 180730 4942500 vi.Non-Workers 1683620 39262349 vii.Language spoken in the District & Tamil,Telugu,Sourastra, English, State Hindi, Malayalam, Gujarathi 3. VITAL STATISTICS 2015-16 2013 i Births (Rural) 25800 -- ii Deaths (Rural) 10734 -- iii Infant Deaths (Rural) 415 -- iv Birth Rate (per1000population) (a) Rural 15.25 15.7 (b) Urban 16.64 15.5 v Death Rate (per1000 population) (a) Rural 6.46 8.1 (b) Urban 4.39 6.3 vi IMR (a) Rural 16.6 24 (b)Urban 10.6 17 1 Madurai Dist Tamilnadu 2015-16 vii Expectation of life at birth 2011-15 (a) Male 68.60 68.60 (b) Female 71.80 71.80 No. -

List of Polling Stations for 197 உசிலம்பட்டி Assembly Segment Within the 33 ேதன� Parliamentary Constituency

List of Polling Stations for 197 உசிலம்பட்டி Assembly Segment within the 33 ேதன Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling Location and name of building Polling Areas Whether for All station in which Polling Station Voters or Men No. located only or Women only 12 3 4 5 1 1 Pt. Union Middle School, Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Uthappanaickanur Ward 1, All Voters ,Eastern Side, North Asbestos Roofed Building, Uthappanaickanur-625537 2 2 Pt. Union Middle School, 1. Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Uthappanaickanur Ward 2, All Voters Eastern Side, North Asbestos 2.Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Vadipatti Ward 1 Roofed Building, Uthappanaickanur-625537. 3 3 Pt. Union Middle School, , 1.Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Uthappanaickanur Ward 2 All Voters South West Terraced Building, Uthappanaickanur - 625537 4 4 Pt. Union Middle School, , Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Maruthampatti Ward 1, All Voters East Side New Addl. Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Sakkiyar Street Ward 2, Building,,Uthappanaickanur - Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Ayenkovil Patti Ward 3, 625537 Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanacikanur (p) - Kulathupatti Ward 4, Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanacikanur (p) - Uthappanaickanur Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanacikanur (p) - Usilampatti 5 5 Pt. Union Ele.school, , addl. Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Pudukkottai Ward 4, All Voters R.C.C Building, U.Pudukottai - Uthappanaicanur (p) - Kannimarpuram Ward 4 625537 6 6 Pt.Union Ele.School ,addl. Uthappanaickanur (r.v) Uthappanaickanur(p) - Mondikundu Ward 1, Uthappanaickanur All Voters R.C.C. Building, Mondikundu - (r.v) Uthappanaickanur (p) - Muppidaripatti Ward 2 625537 Page Number : 1 of 49 List of Polling Stations for 197 உசிலம்பட்டி Assembly Segment within the 33 ேதன Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling Location and name of building Polling Areas Whether for All station in which Polling Station Voters or Men No. -

Madurai District

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 TOTAL POPULATION AND POPULATION OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES FOR VILLAGE PANCHAYATS AND PANCHAYAT UNIONS MADURAI DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS TAMILNADU ABSTRACT MADURAI DISTRICT No. of Total Total Sl. No. Panchayat Union Total Male Total SC SC Male SC Female Total ST ST Male ST Female Village Population Female 1 Madurai East 36 1,37,440 69,590 67,850 33,110 16,718 16,392 58 29 29 2 Madurai West 29 85,771 43,063 42,708 23,777 11,807 11,970 339 182 157 3 Thiruparankundram 38 1,69,335 85,548 83,787 25,632 12,805 12,827 1,447 732 715 4 Melur 36 1,28,717 64,787 63,930 24,477 12,431 12,046 207 95 112 5 Kottampatti 27 1,14,339 57,342 56,997 17,058 8,632 8,426 6 2 4 6 Vadipatti 23 73,498 36,977 36,521 20,440 10,161 10,279 1,136 577 559 7 Alanganallur 37 88,785 44,649 44,136 19,462 9,768 9,694 1,335 694 641 8 Usilampatti 18 73,405 37,664 35,741 11,919 6,120 5,799 161 80 81 9 Chellampatti 29 87,132 44,634 42,498 15,065 7,562 7,503 14 10 4 10 Sedapatti 31 96,182 48,574 47,608 28,270 14,306 13,964 139 67 72 11 Thirumangalam 38 1,05,038 53,186 51,852 22,112 11,032 11,080 2 2 - 12 T.