Bachelor Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Report

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Country Report Egypt April 2013 Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square London E14 4QW United Kingdom _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For 60 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Economist Intelligence Unit Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square The Economist Group London 750 Third Avenue E14 4QW 5th Floor United Kingdom New York, NY 10017, US Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Hong Kong Geneva Economist Intelligence Unit Economist Intelligence Unit 60/F, Central Plaza Rue de l’Athénée 32 18 Harbour Road 1206 Geneva Wanchai Switzerland Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Tel: (41) 22 566 2470 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 Fax: (41) 22 346 93 47 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] This report can be accessed electronically as soon as it is published by visiting store.eiu.com or by contacting a local sales representative. The whole report may be viewed in PDF format, or can be navigated section-by-section by using the HTML links. -

EU-Egypt Task Force - Co-Chairs Conclusions

EU-Egypt Task Force - Co-chairs conclusions The first meeting of the joint Egypt-European Union (EU) Task Force took place on 14th November in Cairo as agreed on the occasion of the visit of President Mohamed Morsi to Brussels on 13th September. The Task Force was launched by Egyptian Foreign Minister Mohamed Kamel Amr and Catherine Ashton, EU High Representative/Vice president and was inaugurated by Egypt's Prime Minister H.E. Dr. Hisham Kandil. Ministers of the Egyptian Government, European Foreign Ministers, EU Commissioners, Members of Parliament, President of the EIB, International Financial Institutions’ senior officials, business leaders, the Secretary General of the UfM, as well as representatives from civil society, participated in the Task Force. The Task Force was the occasion for the EU to send a strong political message in support of the democratic reform process Egypt has embarked on following the 25th January 2011 revolution, in which the Egyptian people demanded their legitimate political and socio-economic rights, particularly freedom, social justice, dignity and prosperity. A new era in EU-Egypt relations for a closer partnership A new era in the relationship between the EU and the new Egypt has started. As equal partners, with common aspirations and values, we are willing to work as closest allies. This mutually-beneficial partnership is based on solid co- ownership, mutual respect and complementarity of interests. It aims at ensuring sustainable inclusive economic growth and socio-economic development, through creating jobs, promoting investment, trade, tourism, technology transfer, know-how and innovation. In support of the ongoing democratic transformation, Egypt and the EU will work together to overcome the socio-economic challenges, thus setting an example for the region and beyond. -

The Impact of the Arab Spring on Tourism Deniz Ferreira De Arruda

Facultat de Turisme Memòria del Treball de Fin de Grau The Impact of the Arab Spring on Tourism Deniz Ferreira de Arruda Grau de Turisme Any acadèmic 2018-19 DNI de l‟alumne: Y3467563M Treball tutelat per Lara Ezquerra Guerra Departament d‟Economia de l‟Empresa S'autoritza la Universitat a incloure aquest treball en el Repositori Autor Tutor Institucional per a la seva consulta en accés obert i difusió en línia, Sí No Sí No amb finalitats exclusivament acadèmiques i d'investigació. Paraules clau del treball: Arab Spring, crises, uprising, tourism Abstract The events of the Arab Spring have put the spotlights on North Africa and the Middle East as long-term dictators were right away removed from office and a democratic wave hit the region. Notwithstanding, the outcomes of the Arab Spring revolutions are yet to be defined, what we can determine from the uprisings is that those collective attitudes played a major role in inserting serious challenges to existing political systems. Over the past years Egypt has suffered many crises such as wars, terrorist attacks, internal political tensions and brutal changes in government. As a consequence, all of these had a negative effect on the flow of tourism into the country. This work examines the importance of the dramatic events as a result of these widespread protests and their impact on the status quo especially with regard to tourism in Egypt. 2 Table of Content Abstract 2 Table of Content 3 Index of Figures 4 1. Introduction 5 1.2 Objectives 5 2. Arab Spring 6 2.1 Geographical location 6 2.2 Origin and its course 6 2.3 Consequences of the Arab Spring 7 2.3.1 Tunisia 7 2.3.2 Egypt 8 2.3.3 Other countries 8 3. -

Egypt Weekly Newsletter January 2014, 4Th Quarter

EGYPT WEEKLY NEWSLETTER JANUARY, 2014 (4th QUARTER) CONTENT 1. Political Overview………..........01 2. Economic Overview……..….…..01 3. Banking…………………….……..….04 4. Subsidy………………………………..05 5. Investment……………………..…..06 6. Food Industry………………....….06 7. Energy..….……………………………07 8. IT & Telecom……..…..…………...08 9. Construction..………………………09 10. International Trade..….………10 Compiled by Thai Trade Center, Cairo POLITICAL OVERVIEW Egypt Police General Killed as al-Seesi Weighs Presidency Source: Egypt Indepdent, January 27, 2014 Gunmen killed a senior Egyptian police official a day after the military endorsed a possible presidential run by Defense Minister Abdelfatah al-Seesi. Assailants on a motorcycle shot Major General Mohamed al-Saeed, director of the Interior Ministry’s technical office, said Ahmed Dawoud, an officer at the Giza investigations unit. A day earlier, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces said that the public wants al-Seesi, who hasn’t announced his plans, to run for election and it’s up to him to “shoulder the responsibility.” The assassination spotlights the security woes that have fueled calls for al-Seesi, who ousted Islamist President Mohamed Mursi in July, to run for the top job. His critics accuse him of leading the bloodiest crackdown against Islamists in decades since Mursi’s ouster, and say the country is turning back into a police state. Mursi went on trial today in the second of four criminal cases against him. “Al-Seesi has a strong support base pushing for him to run,” said Islam Al Tayeb, a research analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London . “And if he runs, he will highly likely win.” ECONOMIC OVERVIEW Egypt Central Bank receives additional $2 billion from Saudi Arabia Source: Egypt Economist, January 28, 2014 Egypt's Central Bank (CBE) received $2 billion from Saudi Arabia, the Egyptian daily Al-Mal reported on Wednesday. -

Page 01 Dec 05.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Thursday 5 December 2013 1 Safar 1435 - Volume 18 Number 5904 Price: QR2 Record-breaking G) facility will produce 110,000 boe (barrels of oil equivalent) per day Engine problems eck Floating LNG facility floating LNG Flare thwart Team ship launched Qatar re uble- to scale Business | 20 Sport | 24 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Qatar, Turkey sign energy deal Met forecasts Commercial foggy morning, low visibility hubs planned DOHA: It will be foggy early this morning with low visibil- ity at places, the Meteorology Department said in its forecast yesterday. in Doha, Rayan Visibility could be as low as one kilometre at places but the mist would clear as the day breaks. Al Khor will be the coolest Move may push rents up place in the country with the minimum temperature forecast DOHA: The Ministry of Street, has been earmarked for at 15 degrees Celsius. Municipality and Urban conversion. In Al Murra in Al The day temperatures is Planning has announced plans Rayan municipality, Al Faroosia expected to be 24 degrees C. to convert several major areas Street has been chosen for con- Elsewhere in the country, day of Doha and some in the neigh- version into a commercial area. and night temperatures would bouring municipality of Al In Al Aziziya suburb, which vary between 18 and 27 degrees Rayan into commercial hubs. is also in Al Rayan municipal- C, except in Dukhan and Abu Shops, showrooms and offices ity, Othman bin Affan Street has Samra where the minimum tem- will be located on both sides of been identified for development perature forecast is 15 degrees the proposed hubs to be known into a commercial hub. -

Egypt's Interim Cabinet: Challenges and Expectations | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2106 Egypt's Interim Cabinet: Challenges and Expectations by Adel El-Adawy Jul 23, 2013 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Adel El-Adawy Adel El-Adawy was a 2013-2014 Next Generation Fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis Cairo's formation of a new cabinet marks the first step toward transition to an elected government. gypt's new interim cabinet held its first official session on July 21, and the mere fact that a new government is E in place will plant the first seeds of stability. Yet this cabinet is unique from a historical perspective, as its agenda has already been established by the military with the agreement of all political forces except the Muslim Brotherhood: namely, to oversee the rapid political transition to an elected government. In the past, especially under Hosni Mubarak, the cabinet's agenda was shaped by the presidency, but current interim president Adly Mansour is a pure figurehead without any political agenda or leverage. Instead, the military has set a defined transitional roadmap and will make sure the civilians in the cabinet follow it. All ministers understand the parameters under which they are allowed to operate and will not deviate from them. RETURN OF THE OLD GUARD T he cabinet's makeup does not carry an overwhelming revolutionary flavor, as no youth leaders are among the appointees. At this stage, however, such an approach makes sense given the transitional government's temporary nature and the need for experienced technocrats. The appointees have been well received by the international community; as Secretary of State John Kerry put it, "I know a number of them personally, and I know they are extremely competent people." Yet the new cabinet has one major drawback: the reemergence of the old guard, who hold several prominent seats on the thirty-five-member body. -

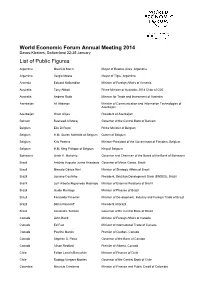

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Annual Report 2016

Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 Egyptian Businessmen’s Association Contents Chapter One: Introduction Activities of EBA in 2016 First: Board Members Second: Sectoral Committees Third: Joint Business Councils Fourth: Activities of EBA on the Internal Level Fifth: Activities of EBA on the International Level & Membership Affairs Sixth: Business Dinners Chapter Two: Economic Indicators for 2016 General Recommendations First: Deposits – Loans & Credit Facilities – Securities Second: National Overall Budget Third: Trade Balance Fourth: Local Investments Fifth: Gross Domestic Product Sixth: Domestic & External Debt Seventh: Balance of Payments Chapter Three: Working Papers for 2016 Annual Report 2016 Egyptian Businessmen’s Association Chapter One Activities of EBA in 2016 Annual Report 2016 Egyptian Businessmen’s Association First: Board Members The Board of Directors was formed of the following members: S Name Position 1 Eng. Ali Helmy Eissa Chairman 2 Eng. Fathallah Fawzi Vice chairman 3 Eng. Amr Hassan Allouba Secretary General 4 Dr. Taha Mahmoud Khaled Treasurer 5 Mr. Adel El Lamei Board Member 6 Eng. Ahmed Balbaa Board Member 7 Eng. Hassan El Shafei Board Member 8 Eng. Magd El Manzalawi Board Member 9 Eng. Mohamed Ayman Kamal ElDin Kora Board Member 10 Dr. Nader Ryiad Board Member 11 Dr. Sherif El Gabaly Board Member Legal Consultant to the 12 Mr. Counsellor Mahmoud Fahmy board Mr. Mohamed Youssef – The Executive Director of EBA Annual Report 2016 Egyptian Businessmen’s Association Second: Sectoral Committees The sectoral Committees were headed by: S Committee Chairman Committee 1. Mr. Adel El Lamei Transport 2. Eng. Ahmed Balbaa Tourism 3. Eng. Alaa Diab Agriculture 4. Dr. Ali Al Korey Environment 5. -

State's Islam and Forbidden Diversity Shia and the Crisis

STATE’S ISLAM AND FORBIDDEN DIVERSITY SHIA AND THE CRISIS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOMS IN EGYPT 2011-2016 Analytical report State’s Islam and Forbidden Diversity Shia and The crisis of Religious freedoms in Egypt 2011-2016 Analytical report Issued by the Civil Liberties Unit Amr Ezzat and Islam Barakat First printing June 2016 Designed by Mohammed Gaber with support from Omniya Naguib Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 al Saray al Korbra St., Garden City, Al Qahirah, Egypt. Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Amr Ezzat, researcher and “freedom of religion and belief” program officer, was the lead author of this report. Assistant researcher Islam Barakat prepared the documentation section. Material for the report was collected in part by Mohammed Kashef and Ahmed Mahrous with the fieldwork team, the EIPR legal team, and research interns Sara al-Masri, Amir Hussein, Mohammed Medhat, and Ibrahim al-Sharqawi. State’s Islam and Forbidden Diversity Shia and The crisis of Religious freedoms in Egypt 2011-2016 Analytical report Introduction This report documents and analyzes the state of religious freedom for Shia Egyptian citizens and violations of their human rights from January 25, 2011 to May 2016. The report takes 2011 as its starting point because that year constitutes a turning point in issues of religious freedom and challenges in the country as a whole, particularly for Egyptian Shias. -

이집트 신정부 수립 100일 이후 경제 및 진출환경 전망 Contents

G lobal M arket Report 12-063 2012.10.05 이집트 신정부 수립 100일 이후 경제 및 진출환경 전망 CONTENTS 목 차 요 약 / 3 I. 2012 대선 이후 이집트 정세 / 4 1. 대선 이후 이집트 정세 / 4 2. 신정부의 외교정책 및 대외활동 / 8 3. 신정부의 당면과제 / 9 참고 1. 2012 이집트 대선 최종 결과 / 11 참고 2. 무르시 대통령 주요 경력 / 12 II. 신정부의 경제정책 분석 / 13 1. 주요 경제정책 방향 / 13 2. 대외경제협력 / 15 III. 대선 이후 이집트 경제 및 진출환경 전망 / 21 1. 이집트 경제 동향 / 21 2. 진출환경 전망 (무역, 투자, 지역개발) / 25 3. 현지 진출기업 및 바이어의 진출환경 전망 / 34 Ⅳ. 시사점 / 36 Global Market Report 12-063 요 약 □ 2012년 6월 24일 이집트 민주화 운동 이후 첫 대선 결과 발표. 무슬림형제단 출신의 무함마드 무르시 대통령 당선 □ 무르시 대통령은 7월 24일 히샴 칸딜 총리 지명과 함께 8월 2일 35개 부처 내각을 구성하여 발표. 8월 12일 이집트 군최고위원회(SCAF)가 6월에 발표한 임시헌법을 폐지하고 신 헌법선언, 군부 주요인사를 해임 등 군부에 분점된 정권을 신정부로 집중 - 향후 신 헌법제정과 하원선거 진행상황과 결과가 정세에 영향을 미칠 전망 □ 무르시 대통령은 사우디, 중국, 이란, EU, 미국 등 활발한 방문외교를 추진, 경제 재건을 위한 국제사회의 지원을 확보 - 아프리카연맹, 이슬람협력기구, 아랍연맹 회의 참석을 통해 이집트 정부의 대외 위상을 재확립 □ 주요 경제정책으로는 ▲이슬람 금융 도입 및 보조금 제도 개혁을 통한 재정적자 완화, ▲해외투자유치와 자국 산업 육성을 통한 무역적자 해소, ▲실업 완화를 위한 노동법 개정 및 노동집약산업 육성, ▲지역 균형발전을 위한 특화 산업 개발 중심으로 추진 - 지역개발 및 인프라 구축 프로젝트로 카이로-알렉산드리아 고속철도 건설, 카이로 메트로 연장, 수에즈 산업단지 개발, 전력 인프라 확충, 담수화 플랜트, 항만 확장 프로젝트 등 추진을 계획 □ 민주화 운동 이후 수립된 첫 민주정부로 국제사회의 환영과 지원을 받고 있으며, 사우디 정부로부터 15억 달러, 8월 중국 방문시 양국 공동사업을 위한 7,000만 달러 무상원조를 받음 - 이집트 정부는 8월 IMF 총재 방문시 48억 달러의 차관을 공식 요청하였으며 현재 차관 제공 협상 중 □ 무르시 정부는 민주화 운동으로 악화된 치안 확보와 경제 재건에 주력하고자 하며, 산업 육성, FTA 체결, 투자환경 개선 등 대외개방 경제정책 가시화시 우리기업의 진출 기회로 작용할 전망 - 특히 정부 주도 프로젝트 추진시 자금 조달의 제약으로 민관합동투자(PPP) 방식이 주로 활용될 것으로 예상 3 Global Market Report 12-063 Ⅰ 2012 대선 이후 이집트 정세 1. -

National Flag and Emblem Locator Map TEXT HIGHLIGHTS

EGYPT National Flag and Emblem Locator Map TEXT HIGHLIGHTS: Diaries updates, key events, brief analysis and relating news articles in timeline Overview It’s name derived from Greece word ‘Aegyptus’ meaning for “dark soil” Long known for its pyramids and ancient civilization, Egypt is the largest Arab country and has played a central role in Middle Eastern politics in modern times. Arabs introduced Islam and Arabic in 7th century and ruled the hitherto predominantly Christian country for six centuries. Mamlukis took control around 1250. Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1517. After completion of the Suez Canal, Egypt became a transport hub but also fell in debts. Britain took over control of Egypt in 1882. Egypt received in 1922 nominal independence from the UK. Kingdom of Egypt (1922–53) held an enthronement rite for its last ruling king, Farouk I. Headship since independence: King Farouk Monarchial Head King Farouk I of Egypt (Fārūq al-Awwal) (11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965), was the tenth ruler from the Muhammad Ali Dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I of Egypt, in 1936. His full title was "His Majesty Farouk I, by the grace of God, King of Egypt and Sudan, Sovereign of Nubia, of Kordofan, and of Darfur." He was overthrown in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 and forced to abdicate in favor of his infant son Ahmed Fuad, who succeeded him as Fuad II of Egypt. He died in exile in Italy. In 1952 the Egyptian military staged a coup and overthrew the British backed monarchy acquired full sovereignty. -

List of Participants As of 19 January 2014 (Subject to Regular Updates)

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting List of Participants As of 19 January 2014 (subject to regular updates) Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 22-25 January 2014 Park Geun-hye President of the Republic of Korea Faisal Abbas Editor-in-Chief Al Arabiya News Channel, United Arab Emirates English Service Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Zein Abdalla President PepsiCo Inc. USA Mustafa Partner and Chair of the Management The Abraaj Group United Arab Emirates Abdel-Wadood Executive Committee Ziad Abdul Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Khalid Honorary Chairman Vision 3 United Arab Emirates Abdulla-Janahi Rovnag Abdullayev President SOCAR (State Oil Company Azerbaijan of the Azerbaijan Republic) Shinzo Abe Prime Minister of Japan Shuhei Abe President, Chief Executive Officer and SPARX Group Co. Ltd Japan Group Chief Investment Officer Fazle Hasan Abed Founder and Chairperson BRAC Bangladesh Derek Aberle Executive Vice-President, Qualcomm Qualcomm USA Incorporated and Group President Bassam A.Salam M. Member of the Board of Directors and Salam International Qatar Abu Issa Executive Director Investment Ltd Mikhail A. Abyzov Minister for Relations with the Open Government of the Russian Federation Aclan Acar Chairman of the Board of Directors Dogus Otomotiv AS Turkey Enrique Acevedo Anchor Univision USA Paul Achleitner Chairman of the Supervisory Board Deutsche Bank AG Germany Gastón Acurio Founder and Chef Astrid & Gastón S R Ltda Peru Timothy Adams President and Chief Executive Officer Institute of International USA Finance (IIF) Charles Adams Managing Partner, Italy Clifford Chance Italy Akinwumi Ayodeji Minister of Agriculture and Rural Adesina Development of Nigeria Tedros Adhanom Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus David Adjaye Architect Adjaye Associates USA Steve Adler President and Editor-in-Chief Thomson Reuters USA World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 1/76 Anat Admati George G.