HEALING MIRRORS Body Arts and Ethnographic Methodologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

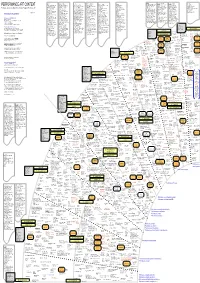

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Guide to the Colin De Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection Processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Hannah Mandel; Collection processed by Ann Butler, Ryan Evans and Hannah Mandel. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 06, 2019 . Describing Archives: A Content Standard Guide to the Colin de Land and Pat Hearn Library Collection MSS.012 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Scope and Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Arrangement .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .................................................................................................................................... -

Elke Silvia Krystufek *1970, Vienna, Austria — Vienna, Austria

CROY NIELSEN Parkring 4, 1010 Vienna, Austria, +43 676 6530074, [email protected] Elke Silvia Krystufek *1970, Vienna, Austria — Vienna, Austria Education 1988 – 1992 Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna Selected Solo Exhibitions 2020 Rechtsstaat/Oida/Constitutional State, Man, Galerie Bernd Kugler, Innsbruck 2019 30 Years – No Overview, Croy Nielsen, Vienna 2018 LUXUS, Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Palais, Vienna 2017 Colleagues, Kronos Advisory, Vienna 2015 Mode, Combinat, Museumsquartier, Vienna 2014 HARMONIE 32, Nicola von Senger, Zürich HARMONIE 19, Meyer Kainer, Vienna 2013 HARMONIE 26, Salon Jirout, Berlin 2012 HARMONIE 8, Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers 2011 Locals and Immigrants, Galerie Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles 2010 Heb, Autocenter, Berlin 2009 Less Male Art, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover 2008 Bedeutungszuwachs, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin 2006/2007 Liquid Logic – The height of knowledge and the speed of thought, MAK Museum, 1 / 10 CROY NIELSEN Parkring 4, 1010 Vienna, Austria, +43 676 6530074, [email protected] Vienna 2005 Futurology: L’etat C’est moi Das Geld bin ich, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin Elke Krystufek Proper Use, MDD, Museum Dhondt Dhaenens, Deurle 2004 Lovers Mind Wide Open, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen Der soziographishe Blick: Blick View#6 Elke Krystufek. The constant lover Faster Than The Speed of Light, Kunstraum Innsbruck 2003 Nackt und mobil, GEM Museum fuer Aktuelle Kunst, Den Haag, Sammlung Essl, Klosterneuburg Communifrontationsilence, Galerie Akinci, Amsterdam 2002 Silent screamm, Kenny Schachter -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

– Performance – Vii from the Guest Editors

A Journal Devoted to the Study of Austrian Literature and Culture Volume 42, Number 3, 2009 – Performance – vii From the Guest Editors ix Contributors Articles 1 Culture as Performance Erika Fischer-Lichte This article describes the trajectory and key issues of “Cultures of Performance,” the ongoing collaborative research project at the Free University Berlin on the dynamics of cultural change. It elaborates the central metaphor of “culture as performance” and outlines constitutive features of performances such as the autopoietic feedback loop and the notion of emergence. According to its central hypothesis, the same forces are at work in performance as in culture at large: performance thus becomes a sort of laboratory for studying cultural and social forces. 11 From the Dreamwork of Secession to the Orgies Mysteries Theater Herbert Blau This essay traces the multifarious vicissitudes of dreamwork and performative insolence in modern Austrian theater, psychoanalysis, the visual arts, and performance culture from fin-de-siècle Vienna to the Viennese Actionists. Johann Nestroy is invoked as the key nineteenth-century figure in this tradition of talismanic disobedience; his aggressive satire is a proleptic summary of the theatrical assaults on a smug Austrian culture of grandeur articulated by the modernist artists of Jung-Wien in a much less radical form. IV MODERN AUSTRIAN LITERATURE 29 Importing Valie Export: Corporeal Topographies in Contemporary Austrian Body Art Markus Hallensleben This article traces Valie Export’s impact on Austrian performance and video artists such as Miriam Bajtala, Carola Dertnig, Renate Kowanz-Kocer, Elke Krystufek, and Ulrike Müller. To map atypical Austrian corporeal topographies at the turn of the twenty-first century, the author applies a definition of performance and cultural space based on the work of Merleau-Ponty, Lefebvre, Agamben, and Fischer- Lichte in order to expand Butler’s notion of gender as a performative category to an understanding of the human body as performative space. -

An.Schläge 7–8/2009

9 0 0 2 / 8 0 - 7 0 e g ä l h c s . n a an.schläge DAS FEMINISTISCHE MAGAZIN juli august thema RaumGewinn Feministische Architektur- und Wohnmodelle bauen auf Kollektivität politik RaumVerlust Das FrauenLesbenzentrum Innsbruck baut auf Solidarität e 3,8 (Ö) e 4,5 (D) sfr 9,- P Illustration: Bijan Dawallu, aro a, Berlin typisch! Sonntag–Freitag 10–18 Uhr Juden und Anderen und Juden Dorotheergasse 11,WienDorotheergasse 1 Klischees von Klischees von 1.4.– Palais Eskeles Palais www.jmw.at 11.10.2009 Ein Unternehmender an.schläge an.spruch Klum ist ein Stahlbad auf.takt Was hätte Adorno zu Germany’s Next Topmodel gesagt? 05 eu.politik Wie wohnt es sich feministisch, fragt das Thema Europas Stimme? dieser Ausgabe anlässlich der bevorstehenden Die EU-Wahl als Abstimmung über Gleichstellungspolitik 08 Fertigstellung zweier neuer Frauenwohnprojekte in Wien.Wodurch zeichnet sich feministische frauen.lesben.zentrum (Innen-)Architektur aus, wodurch feministische Keine Geschenke Raumplanung, und welche Modelle alternativer Der Frauenraum in Innsbruck steht vor dem Aus 10 Raumgestaltung und -nutzung wurden von Frauen entwickelt? mädchenbildung.kamerun k i t Und ist es überhaupt sinnvoll, speziell für i Recht auf Bildung l o Frauen zu bauen und zu planen, oder werden da- p Ein Ausbildungszentrum will Waisenmädchen fördern und vernetzen 14 durch traditionelle Geschlechterordnungen erst recht in Beton gegossen? Welche Frauen geschlechter.raum gehören dabei zur Zielgruppe – und welche Wohnen in Rosa nicht? (S. 17 ff) Feministischer Architektur und Raumplanung auf der Spur 17 Dass Räume als Ausdruck von gesellschaftli- chen Macht- und Ordnungsverhältnissen auch raum.geschlechter a stets umkämpftes Terrain sind, zeigt sich am Bei- m Common spaces, common concerns? e h spiel des von der Schließung bedrohten autono- t Wie lassen sich soziale Räume feministisch verändern? 20 men FrauenLesbenzentrums in Innsbruck. -

Catalog Vernissagetv Episodes & Artists 2005-2013

Catalog VernissageTV Episodes & Artists 2005-2013 Episodes http://vernissage.tv/blog/archive/ -- December 2013 30: Nicholas Hlobo: Intethe at Locust Projects Miami 26: Guilherme Torres: Mangue Groove at Design Miami 2013 / Interview 25: Gabriel Sierra: ggaabbrriieell ssiieerrrraa / Solo show at Galería Kurimanzutto, Mexico City 23: Jan De Vliegher: New Works at Mike Weiss Gallery, New York 20: Piston Head: Artists Engage the Automobile / Venus Over Manhattan in Miami Beach 19: VernissageTV’s Best Of 2013 (YouTube) 18: Héctor Zamora: Protogeometries, Essay on the Anexact / Galería Labor, Mexico City 17: VernissageTV’s Top Ten Videos of 2013 (on Blip, iTunes, VTV) 13: Thomas Zipp at SVIT Gallery, Prague 11: Tabor Robak: Next-Gen Open Beta at Team Gallery, New York 09: NADA Miami Beach 2013 Art Fair 07: Art Basel Miami Beach Public 2013 / Opening Night 06: Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) Preview 05: Art Basel Miami Beach 2013 04: Design Miami 2013 03: Untitled Art Fair Miami Beach 2013 VIP Preview 02: Kris Kuksi: Revival. Solo exhibition at Joshua Liner Gallery, New York November 2013 29: LoVid: Roots No Shoots / Smack Mellon, New York 27: Riusuke Fukahori: The Painted Breath at Joshua Liner Gallery, New York 25: VTV Classics (r3): VernissageTV Drawing Project, Scope Miami (2006) 22: VTV Classics (r3): Bruce Nauman: Elusive Signs at MOCA North Miami (2006) 20: Cologne Fine Art 2013 20: Art Residency – The East of Culture / Another Dimension 15: Dana Schutz: God Paintings / Contemporary Fine Arts, CFA, Berlin 13: Anselm Reyle and Marianna Uutinen: Last Supper / Salon Dahlmann, Berlin 11: César at Luxembourg & Dayan, New York 08: Artists Anonymous: System of a Dawn / Berloni Gallery, London 06: Places. -

Biography Elke Silvia Krystufek Selected

Biography Elke Silvia Krystufek Selected Solo Exhibitions - 2020 - Solo Exhibition, Galerie Bernd Kugler, Innsbruck - 2019 - Elke Silvia Krystufek, stayinart @ Art Bodensee Elke Silvia Krystufek, Galerie Croy Nilsen @ Art Basel, CH Elke Silvia Krystufek, stayinart @ ART VIENNA, Hofburg Vienna 30 Years - No Overview, Galerie Croy Nielsen, Vienna - 2018 - LUXUS, Wienerroither&Kohlbacher Palais Schoenborn-Batthyany, Vienna - 2016 - Colleagues, Kronos Advisory GmbH, Vienna - 2015 - MODE, Combinat, Museumsquartier, Vienna - 2014 - HARMONIE 32, Galerie Nicola von Senger, Zurich HARMONIE 19, Galerie Meyer Kainer, Vienna HARMONIE 98 One Gallery, Vienna HARMONIE 98 Buero Weltausstellung, Vienna HARMONIE 19 Galerie Meyer Kainer, Vienna - 2013 - HARMONIE 26, Salon Jirout, Berlin HARMONIE 360, Hausmuseum Dr. Otmar Rychlik, Gainfarn HARMONIE 20, Buero Weltausstellung & Kunstraum am Schauplatz, Vienna - 2012 - HARMONIE 8, Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers HARMONIE 20, Haus am Waldsee, Berlin, (prohibited by Dr. Katja Blomberg) HARMONIE 5, Galerie Nicola von Senger, Zurich - 2011 - Locals and Immigrants, Galerie Susanne Vielmetter, Los Angeles HARMONIE 3, The Box Gallery, Los Angeles HARMONIE 2, Vegas Gallery, London - 2010 - Heb, Autocenter, Berlin - 2009 - Less Male Art, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover Der Sex ist im Text, Galerie Nicola von Senger, Zurich The female gaze at the male or unmale man, Galerie Meyer Kainer, Vienna - 2008 - Bedeutungszuwachs, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin Mother Observing, Galleria Il Capricorno, Venice A FILM CALLED WOOD..., Transit Art Space, Stavanger Power Change initiated by a woman, Ulmer Museum, Ulm Responsible for a certain amount of Luck, Camera Austria, Graz - 2006/07 - Liquid Logic - The height of knowledge and the speed of thought, MAK Museum fuer angewandte Kunst, Vienna The Visible Woman, Nicola von Senger Galerie, Zurich - 2005 - Futurology: L etat C est moi - Das Geld bin ich, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin Elke Krystufek Proper Use, MDD, Museum Dhondt Dhaenens, Deurle - 2004 - Der soziographishe Blick: Blick View#6 Elke Krystufek. -

The Transfer of the Essl Collection to the ALBERTINA Vienna, 16 February 2017

Press Conference The transfer of the Essl Collection to the ALBERTINA Vienna, 16 February 2017 0 Contents The transfer of the Essl Collection to the ALBERTINA 2 Holdings of the Essl Collection 5 The Essl Collection 7 Chronology of the Essl Collection 10 Biography of Agnes and Karlheinz Essl 11 1 The transfer of the Essl Collection to the ALBERTINA Effective today, the Essl Collection is being officially transferred to the ALBERTINA in Vienna. This marks the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the Essl Collection as well as the Albertina itself. And at the same time, this acquisition of one of the largest private collections of contemporary art represents a milestone in the history of the Austrian Federal Museums. With its over 6,000 works, the Essl Collection numbers among the world’s largest private col- lections of its kind. Groups of works by figures including Karel Appel and Arnulf Rainer, Franz West and Georg Baselitz, Maria Lassnig and Alex Katz, Erwin Wurm and Anselm Kiefer, VALIE EXPORT and Cindy Sherman, and photographs by artists ranging from Andreas Gursky to Can- dida Höfer characterise this collection’s unique richness and special profile. In 2014, the Essl Collection was in danger of being caught up in the financial turbulences sur- rounding the group of companies owned by the Essl family. But that same year, the collec- tion—in no small part thanks to the efforts of Dr. Hans Peter Haselsteiner—was placed under the ownership of a new company, thus ensuring its survival. Now, its permanent loan (until 2044) to the ALBERTINA places the Essl Collection beneath the umbrella of the Austrian Fed- eral Museums. -

Preview Exhibitions 2020 Press Release.Pdf

Having Lived Ingeborg Strobl Press conference: Wednesday, March 4, 2020, 10 am Ingeborg Strobl’s oeuvre is moored in the tradition of conceptual and intermedia art. Opening: Natural and animal subjects acting as mirror images of society take up a central role Thursday, March 5, 2020, 7 pm in her objects, installations, collages, paintings, photographs, films, and publications. Duration of the exhibition: Also evident in her work is a predilection for the marginal, the hidden, that which is March 6 through Julne 21, 2020 all-too easy to overlook or repress as well as a concomitant aversion to obsessive production and consumption. Recognizing and valuing the peripheral is an aspect that also comes to the fore in the media in which she worked. Printed matter such as publications, posters, and invitation cards are themselves artistically rendered compo- nents of her oeuvre. Strobl donated her archive with numerous works and printed matter to mumok. This archival material is the centerpiece of the retrospective, which was conceived in col- laboration with the artist—before her death in April 2017—and gives a representative overview of her comprehensive oeuvre. Ingeborg Strobl The exhibition is focused on—previously rarely shown—early ceramics, which the Eat / Horse, 1996 ©1996 Ingeborg Strobl / artist created during her studies in London. Strobl’s sense of beauty that is hidden Bildrecht Wien in transient things as well as the fugacity of all magnificence is already manifest in Photo: © mumok these early works. In a multitude of detailed colored-pencil drawings from the 1970s, she translates the ceramic works’ surreal illusionism into the pictorial. -

Complete List of Exhibitions (Pdf)

EXHIBITIONS 1989 - 2021 EXHIBITIONS 1989 ANDREAS GURSKY Photographs From April 5 until May 20, 1989 HENRI MICHAUX 50 works on paper (inks, watercolours, gouaches) Exhibition catalogue From May 31 until July 15, 1989 EMMETT WILLIAMS Edition – exhibition, together with the Festival de Poésie Sonore, Geneva (performance) Edition of a book-object, La dernière pomme frite et autres poèmes des fifties et sixties From September 18 until October 28, 1989 EXHIBITIONS 1990 ANDREAS HOFER Installation - edition From February 10 until March 24, 1990 ANNE PESCE Exposition - edition Edition of an artist’s book, Pêcheur c'est lui qui devient un poisson, 1990 From March 29 until May 12, 1990 JEAN-MARC MEUNIER Sapins de Noël (1988-1989) Photographs From May 31 until July 14, 1990 ROMAN SIGNER Installation - hélicoptère Exhibition – edition of a video From October 26 until December 8, 1990 EXHIBITIONS 1991 JEAN-MICHEL OTHONIEL Exhibition – edition From February 15 until April 6, 1991 MARCEL BROODTHAERS Exhibition of editions and books by Marcel Broodthaers, and publication of a catalogue with critical texts by specialists of Broodthaers’ œuvre. Presentation of a selection of his films at the MJC – Saint-Gervais, Geneva. Essays by: Rainer Borgermeister, Johannes Cladders, Michael Compton, Philippe Cuenat, Yves Gevaert, Alain Jouffroy, Anne Rorimer, Dieter Schwarz. From May 31 until July 20, 1991 SUZANNE LAFONT Photographs From October 11 until November 23, 1991 LAURENCE PITTET Exhibition – edition From December 6, 1991, until January 11, 1992 EXHIBITIONS 1992 MARIE SACCONI Exhibition – edition of an artist’s book, Madame B. a ri Exhibition of drawings and recent work From January 17 until February 8, 1992 STEPHAN LANDRY Edition of an artist’s book and a colour lithograph, Esquive Exhibition of drawings, and in situ intervention From February 13 until March 7, 1992 JEAN STERN Exhibition and edition of two series of book-objects, Panini alle melanzane From March 12 until April 4, 1992 PARKETT Exhibition of all editions made by the magazine PARKETT (1984-1992).