Taking the High Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson River Park Case Study.Indd

Hudson River Park Jordan Bell David Tomlinson Above: Boardwalk; from Hudson River Park .org Photo Left: people using the park from DPD study Hudson River Park is largest park in manhattan to be built since Central Park was built in mid 19th century. The park consists of a fi ve mile long strip covering 550 acres running up the western side of manhattan from the northern end of Battery Park City at the south end to 59th street at the northern end. The park includes renovation of over a dozen derelict piers, the creation of a bikeway, and a pedestrian promenade. A mix of pubic functions are incorporated into the design such as ball fi elds and large recreational lawns as well as interspersed commercial space. After the west side Highway was closed in 1972 the space has been in need of revitalization and local neighborhoods have been advocating for a new roadway and parks. The park planning process really got underway starting in the early 90’s with plans for a bike and pedestrian path. PAGE # 1 NEW YORK CITY HUDSON RIVER PARK “This is the Central Park of the 21st Century... an innovative design that preserves the ecology of the Hudson and creates a world class venue from which to experience all the New York waterfront has to offer” -Governor Pataki Planning approach Early planning for the project began in early nineties with the formation of the Hudson River Park Conservancy in 1992. Through the 90’s the Conservancy worked to construct new bike and pedestrian connections and started a public planning process that created a concept and fi nancial plan. -

Media Kit 2020

Media Kit 2020 One MetroTech Center North, 3rd Floor • Brooklyn, NY 11201 • (770) 881-7085 • [email protected] Reach More People More Ways Than Any Other Media Company In The New York And Philadelphia Market. Offers A Wide Range Of Media Solutions Across Print, Outdoor, Digital, Events And Broadcasting Channels. Reaches Over 3.0 Million People Every Week In New York, Philadelphia And Beyond. Schneps Media Reaches More People More Ways Than Any Other Media Company In The New York Market NYC MANHATTAN BROOKLYN QUEENS BRONX Chelsea Now Bay News Queens Courier Bronx Times NEWSPAPERS amNY METRO Downtown Express Brooklyn Graphic Courier Sun Bronx Times Reporter Caribbean Life Manhattan Express Brooklyn Paper Bayside Times Bronx Weekly El Correo The Villager Mill Basin Marine Park Flushing Times Gay City News Villager Express Courier TimesLedger Park Slope Courier Ridgewood Times Brooklyn Weekly Times Newsweekly Jamaica Times Queens Weekly Cryder Point Courier LeHavre Courier North Shore Towers Courier Airport Voice MAGAZINE & New York Family New York Family Brooklyn Family Queens Family Bronx | Riverdale Family SPECIALITY Family Camp & Summer Family Camp & Summer Family Camp & Summer Family Camp & Summer Family Camp & Summer Guide Guide Guide Guide Guide PUBLICATIONS Wedding Guide Wedding Guide Wedding Guide Wedding Guide Wedding Guide Special Child Aspire Aspire, BFCU’s Best of the Brooklyn Tomorrow Boro, Boro Magazine, LIC Brownstoner Courier Playbill-Flushing Dime Best of Brooklyn Town Hall & Queens One Brooklyn Theatre, Queens in Your Pocket, -

Complete History

The Hotel Albert 23 East 10th Street, NYC Hotel Albert c.1907 Photograph obtained from The Museum of the City of New York A History Prepared by Anthony W. Robins Thompson & Columbus, Inc. April 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 3 PART I: Construction History ........................................................................................ 5 PART II: Descriptions of the Hotel St. Stephen Prior to its Incorporation into the Hotel Albert .................................................................................................... 15 PART III: The Early Years Up To World War I – Descriptions and Visitors ......... 19 PART IV: The Early Years Up To World War I – Resident Writers and Artists ... 30 PART V: From the 1920s Through World War II and Just Afterwards .................. 43 PART VI: From the 1920s Through World War II and Afterward: Writers, Artists and Radicals ................................................................................................... 46 PART VII: 1950s and 1960s – Writers, Artists, Actors And Descriptions Of The Hotel .............................................................................................................. 61 PART VIII: The Albert French Restaurant ................................................................. 69 PART IX: 1960s Musicians ............................................................................................ 89 PART X: End of an Era .............................................................................................. -

The Villager Newspaper

Board 2 hears ideas from storm surge prophets | The Villager Newspaper Our Staff Support Oklahoma ADVERTISING INFORMATION Current Print Edition Buy a copy of The Villager Subscribe to our print edition Get Email updates Home News Opinion Scoopy's Columns Arts Literature In Pictures Pride Meat Market Progress Union Square Volunteers >> JOIN OUR EMAIL NEWSLETTER RSS Thursday, August 15, 2013 Search The Villager Board 2 hears ideas from storm surge prophets January 17, 2013 | Filed under: News | Posted by: admin Stay Tuned… An image from Malcolm Bowman’s presentation on storm surge barriers, showing a view of a segment of the Delta Project, in the Netherlands. The system is composed of a mixture of elevated natural sand dunes, tidal gates (normally open), elevated highways and shipping gates. The photo was taken during flooding (incoming) tides. During storm surges, gates are lowered from the highway for protection. BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Facing a room packed with Village residents, David Gmach, director of public relations for Con Edison, had the task of explaining to them why the power went off in most of Lower Manhattan during Superstorm Sandy and why it stayed off for days thereafter. During Hurricane Irene, there were around 200,000 power outages, he said, out of around 3.1 million customers in the five boroughs and Westchester County. Before Sandy, this was the worst situation that Con Edison had ever encountered. During Sandy, there were 1.1 million customer outages. Gmach, addressing a meeting of Community Board 2’s Environmental Committee, told his audience that out of the 1.1 million Con Ed customers who lost service, around 230,000 were in Manhattan. -

Newspapers by County | New York Press Association

Newspapers by County | New York Press Association http://nynewspapers.com/newspapers-by-county/ Contact Us Become a member Calendar NYPA Board of Directors Contact Us(518) 464-6483 search Home Advertising » Member Services » Newsletters » Contest & Events » Resources » Newspapers by County A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A 1 of 28 8/31/17, 6:51 AM Newspapers by County | New York Press Association http://nynewspapers.com/newspapers-by-county/ Albany Altamont Enterprise and Albany 4345Thursday County Post, The Business Review (Albany), The 6,071Friday Capital District Mature Life 20,000Monthly Capital District Parent 35,000Monthly Capital District Parent Pages 20,000Monthly Capital District Senior Spotlight 18,000Monthly Colonie-Loudonville Spotlight 2885Wednesday Colonie-Delmar-Slingerlands 20213Bi-Thursday Pennysaver Evangelist, The 35,828Thursday Latham Pennysaver 15,861Thursday News-Herald, The 423Thursday Spotlight (Delmar), The 5,824Wednesday Times Union 56,493Daily Allegany Alfred Sun 878Thursday Patriot and Free Press 3,331Wednesday Wellsville Daily Reporter 4,500Tues-Fri B Bennington, VT Northshire Free Press 7,600Friday Bronx Bronx Community News 5,000Thursday Bronx Free Press 17,300Wednesday Bronx News 4,848Thursday Bronx Penny Pincher 78,400 Bronx Penny Pincher (Castle Hill 16,050Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Morris Park 16,200Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Parkchester 8,050Thursday Edition), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Pelham Parkway 15,000Thursday North), The Bronx Penny Pincher (Throggs -

01-04-17-Gansevoort-Project-Has-Strong-Support-From-Area.Pdf

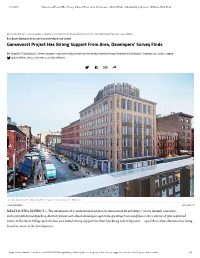

1/4/2017 Gansevoort Project Has Strong Support From Area, Developers' Survey Finds - Meatpacking District - DNAinfo New York GREENWICH VILLAGE & SOHO (//WWW.DNAINFO.COM/NEW-YORK/MANHATTAN/GREENWICH-VILLAGE-SOHO) Real Estate (//www.dnainfo.com/new-york/topics/real-estate) Gansevoort Project Has Strong Support From Area, Developers' Survey Finds By Danielle Tcholakian (//www.dnainfo.com/new-york/about-us/our-team/editorial-team/danielle-tcholakian) | January 25, 2016 2:59pm @danielleiat (http://twitter.com/danielleiat) A rendering of how the Gansevoort Street project will look from the High Line. View Full Caption BKSK Architects MEATPACKING DISTRICT — The developers of a controversial project on Gansevoort Street (https://www.dnainfo.com/new- york/20150826/meatpacking-district/gansevoort-street-developers-get-rude-greeting-from-neighbors) say a survey of 300 registered voters in the West Village and Chelsea area found strong support for their blocklong redevelopment — a poll that critics dismissed as being biased in favor of the development. https://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20160125/meatpacking-district/gansevoort-project-has-strong-support-from-area-developers-survey-finds 1/6 1/4/2017 Gansevoort Project Has Strong Support From Area, Developers' Survey Finds - Meatpacking District - DNAinfo New York Market research firm Fabrizio, Lee & Associates said it found that 58 percent of residents west of 6th Avenue between Charlton and West 25th Streets support the development project planned for 46-74 Gansevoort Street by Aurora Capital -

Inside Greenwich Village: a New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst University of Massachusetts rP ess Books University of Massachusetts rP ess 2001 Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 Gerald W. McFarland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books Part of the History Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation McFarland, Gerald W., "Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918" (2001). University of Massachusetts Press Books. 3. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Massachusetts rP ess at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts rP ess Books by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inside Greenwich Village This page intentionally left blank Inside Greenwich Village A NEW YORK CITY NEIGHBORHOOD, 1898–1918 Gerald W. McFarland University of Massachusetts Press amherst Copyright ᭧ 2001 by University of Massachusetts Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America LC 00-054393 ISBN 1–55849-299–2 Designed by Jack Harrison Set in Janson Text with Mistral display by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound by Sheridan Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McFarland, Gerald W., 1938– Inside Greenwich Village : a New York City neighborhood, 1898–1918 / Gerald W. McFarland. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1–55849-299–2 (alk. paper) 1. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—History—20th century. 2. Greenwich Village (New York, N.Y.)—Social conditions—20th century. -

A Tide of Concern Is Rising Over Risk of Storm Surges | Thevillager.Com

A tide of concern is rising over risk of storm surges | thevillager.com Our Staff Archives WORK FOR US Advertising Information In Print Home Columns Opinion Arts In Pictures Events News Scoopy's Progress Report Thrive >> JOIN OUR EMAIL NEWSLETTER RSS Thursday, January 26, 2012 Stay Tuned… A tide of concern is rising over risk of storm surges December 29, 2011 | Filed under: News | Posted by: admin Print PDF Photo by Terese Loeb Kreuzer A view in August across the Hudson River to Jersey City from Lower Manhattan. Water levels have already risen due to climate change, according to experts. BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | A horror movie could not have been more frightening or more graphic. Hurricane-force winds. Sea levels rising 13 feet over the course of an hour. Thirty-foot storm surges destroying every manmade object in their path. Transportation systems flooded. No potable drinking water. Destroyed ecosystems. Beaches and barrier islands washed away. Two to three million people having to be evacuated. This is what might happen if New York City were hit by a hurricane. Some of this is what has happened from time to time in the past but a future storm would probably be even worse. Climate change has already caused sea levels to rise even without the added stress and dangers of a storm. According to David Bragdon, director of the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability, “By midcentury, New York City’s average temperatures will rise by three to five degrees Fahrenheit, and sea levels could rise by more than two feet. -

Reclaiming the High Line Is a Project of the Design Trust for Public Space, with Friends of the High Line

Reclaiming the High Line is a project of the Design Trust for Public Space, with Friends of the High Line. Design Trust Fellow: Casey Jones Writer: Joshua David Editor: Karen Hock Book design: Pentagram Design Trust for Public Space: 212-695-2432 www.designtrust.org Friends of the High Line: 212-606-3720 www.thehighline.org The Design Trust project was supported in part by a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. Printed by Ivy Hill Corporation, Warner Music Group, an AOL Time Warner Company. Cover photograph: “An Evening in July 2000” by Joel Sternfeld Title page photograph by Michael Syracuse Copyright 2002 by the Design Trust for Public Space, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechan- ical means without written permission from the Design Trust for Public Space, Inc. ISBN: 0-9716942-5-7 RECLAIMING THE HIGH LINE A PROJECT OF THE DESIGN TRUST FOR PUBLIC SPACE WITH FRIENDS OF THE HIGH LINE 1 1 . Rendering of the High Line 2 C ONTENTS FOREWORD 4 by New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg HIGH LINE MAP AND FACT SHEET 6 INTRODUCTION 8 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PUBLIC REUSE 17 Why Save the High Line? Recommendations for a Preserved, Reused High Line HISTORY OF THE HIGH LINE 44 Early Rail Transit West Side Improvement Decline of Rail Commerce The Call for Trail Reuse EXISTING CONDITIONS 56 Current Use Maintenance/Structural Integrity PHYSICAL CONTEXT 58 Zoning Surrounding Land Use Upcoming Development COMPETING OWNERSHIP PLANS 70 Demolition Efforts by Chelsea Property Owners Reuse Efforts by Friends of the High Line Political Climate EVALUATION OF REUSE OPTIONS 74 Demolition/Redevelopment Transit Reuse Commercial Reuse Open Space Reuse Moving Forward THE HIGH LINE AND THE CITY AS PALIMPSEST 82 by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers BIBLIOGRAPHY 84 PROJECT PARTICIPANTS 86 3 New York City would be unlivable without its parks, trees, and open spaces. -

M8 the Villager

M8 THE VILLAGER WEST VILLAGE M8 THE VILLAGER INWOOD UNIVERSITY GREENWICH VILLAGE HEIGHTS BRIDGE EAST VILLAGE The M8 bus ride, “The Villager,” offers a charming and intimate ride through Greenwich Village and the East Village. From the Hudson River to the East River, this 25-minute excursion captures the essence and atmosphere of two of New York’s most popular H A R L E M R I V E R WASHINGTON BRIDGE 178th St and colorful neighborhoods. THE BRONX 168th St The M8 bus operates between Av D/E 10 St and West St/ WASHINGTON HEIGHTS Christopher St daily. MACOMBS DAM BRIDGE 155th St MAJOR SIGHTS ALONG THE WAY – Hudson River Park, 145 ST BRIDGE 145th St the West Village, Jefferson Market Library, Greenwich Village, MADISON AV BRIDGE Cooper Union, St. Marks Place, the East Village, Tompkins 135th St 3 AV Square Park and East River Park. HARLEM BRIDGE TRIBOROUGH BRIDGE 125th St MANHATTAN YOUR GUIDE – Ed Koch, former Mayor of the City of New York, lawyer, author and long-time Village resident, is your guide 110th St for this tour. He describes the sites along the way, interspersed with comments about his political life and insights into events UPPER 96th St that helped shape the Village as we know it today. WEST SIDE YORKVILLE 86th St H U D S O N R I V E R Eight million people call New York City home. Most people UPPER CENTRAL EAST know it as “The Big Apple,” but few realize that, despite its size, PARK SIDE 72nd St the city is really a collection of small diverse “hometowns” and that New York is one of the few remaining cities in America QUEENSBORO 59th St BRIDGE that still supports a middle class. -

Felicia Young CV

Felicia Young ECOLOGICAL, COMMUNITY-BASED ART & CULTURAL ORGANIZING WORK Founder / Executive Director Earth Celebrations Inc., New York City, 1991 - Present Founded Earth Celebrations, a non-profit organization based in New York City dedicated to engaging communities to generate ecological and social change through the arts. Conceived, directed, designed and produced all programming. Built diverse sector partnerships and grassroots coalition efforts through neighborhood and citywide ecological and cultural projects engaging residents, youth, artists, schools, community service centers, academic institutions, municipalities and government officials. Projects raised awareness, mobilized action and impacted policy change including the 15 year Save Our Gardens project that led to the preservation of hundreds of community gardens in New York City. Earth Celebrations Community-Engaged Ecological Art Projects • Ecological City: A Cultural & Climate Solutions Action Project, 2017-2019, Lower East Side, NYC. • Vaigai River Restoration Pageant, 2013-2015, Madurai, South India • Hudson River Restoration Pageant, 2009-2012, Hudson River Park, Downtown, New York City • Save Our Gardens Pageants, 1991-2005, Lower East Side Community Gardens, New York City Earth Celebrations Community Organizing Programs Vaigai River Restoration Project, 2013-2015, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, South India. Initiated and founded an international and local community-engaged ecological and cultural project and citywide effort to restore the Vaigai River Madurai, India. Conceived, built and implemented project, enlisting sponsor/partners: Dr. Geeta Mehta (Asia Initiatives & Columbia University, Department of Urban Studies and Architecture), Dhan Foundation in Madurai, India Lower East Side Garden Preservation Coalition, 1994-1999. Initiated and managed grassroots effort to preserve community gardens and coalition of over 40 gardens New York City Coalition for the Preservation of Gardens, 1996-1999. -

Reusing and Repurposing New York City's Infrastructure

Reusing and Repurposing New York City’s Infrastructure 1 Reusing and Repurposing New York City’s Infrastructure: Case Studies of Reused Transportation Infrastructure By Galin Brooks Executive Summary The High Line, Brooklyn Navy Yards, Pier 40 and Myrtle Avenue Station, are examples of projects that are reinventing how we think about the use of infrastructure spaces in New York City. What are the characteristics that define such projects and how is that they have been successful? This paper attempts to provide answers to this question by reviewing four case studies of repurposed transportation infrastructures, drawing out their commonalities and discussing their policy implications. Infrastructure gives life to cities. It supplies its dwellers with food and other necessities, transports them and keeps them clean and safe. New generations have new needs and require new systems to serve these needs. With new generations also can come new land use patterns, densities and demographics. Changes in the make up of area residents can lead to changes in the fabric of a place. For example, a park may appear on a formerly unused rail bed or sports fields may be built on a former freight transfer station. The urban phenomenon of repurposed infrastructure can occur as a result of many contributing variables, events and individuals. There is no predetermined chain of events. Therefore, an exploration of the context in which these transformations happen is useful. As the most likely users of the sites, the characteristics of the people living in surrounding areas at the time of each case study’s transformation are reviewed. Demographics such as educational attainment, income, length of residence in a community and age were sought.