Walden University 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THOMAS E. REILLY Zucker Family School of Education the Citadel 171 Moultrie Street Charleston, SC 29409 Tel: 843-953-6984 [email protected]

THOMAS E. REILLY Zucker Family School of Education The Citadel 171 Moultrie Street Charleston, SC 29409 Tel: 843-953-6984 [email protected] Education Ed.D, Educational Psychology and Special Education, University of Southern California. M.A., Special Education, George Washington University. M.A.T., School Administration and Supervision, The Citadel. B.S., Health and Physical Education, George Washington University. Academic Work Experience Director, Internships and Field Experiences. The Zucker Family School of Education, The Citadel. 2013- present. Adjunct Professor. The Citadel, Charleston, SC. Courses taught: Child Growth and Development, Human Growth Development, General Psychology, Educational Psychology, The Exceptional Child in the School, and Critical Educational Issues in a Multicultural Society. 2002-present. Upper School Principal. Coastal Christian Preparatory School, Mount Pleasant, SC. 2007-2009. Vocational Special Needs Job Coach, West Ashley High School Charleston, SC. 2006-2007 Varsity Girls Soccer Coach. Academic Magnet High School, Charleston, SC. 2006-2007. Classroom Teacher. Wando High School, Mount Pleasant, SC. Courses taught: CP English IV, Physical Science, Government, Economics, Psychology, Psychology 101, and Emotionally Handicapped Students. 1980-2006. Varsity Boys Soccer Coach. Wando High School, Charleston, SC. 1980-2003. Adjunct Professor – Special Education. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. 1980-1984. Coordinator, Vocational Handicapped Program. Charleston County School District, Charleston, SC. 1979-1980 Teacher – Emotionally Handicapped Adolescents and Boys Soccer Coach. Evergreen High School, Evergreen, CO. 1977-1979. Teacher – Emotionally Handicapped Adolescents and Boys Soccer Coach. Golden High School, Golden, CO. 1975-1977. Assistant Professor – Special Education and Coordinator of Student Teachers. Denver University, Denver, CO. 1974-1975 Director– Diagnostic Prescriptive Teacher Program. -

Aaron H. Oberman, Ph.D. 105 Bald Cypress Court Summerville, SC 29485 (843) 819-7569 [email protected]

Aaron H. Oberman, Ph.D. 105 Bald Cypress Court Summerville, SC 29485 (843) 819-7569 [email protected] Education 2005 Doctor of Philosophy in Education Concentration: Counselor Education and Supervision Specialization: School and Career Counseling Cognate: Psychology University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN CACREP accredited Dissertation: “The job satisfaction of counselor education faculty members” 2001 Master of Arts in Counseling Specialization: Community Counseling West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV CACREP accredited 1999 Bachelor of Arts in Psychology University of South Florida, Tampa, FL Teaching Appointments August 2011 to present Associate Professor (Tenured) School of Education Division of Counselor Education The Citadel, Charleston, SC. CACREP accredited (reaccredited through 2021) August 2006 to July 2011 Assistant Professor School of Education Division of Counselor Education The Citadel, Charleston, SC. CACREP accredited Blackboard and/or Livetext are used as instructional platforms in courses to improve student learning. Oberman 2 Courses Taught: Introduction to Counseling Career Counseling & Development Counseling Theories & Practice Special Topics: Counseling Children (course developer) Special Topics: The School Counselor (course developer) Program Planning, Management, & Evaluation Basic Counseling Skills Practicum in School Counseling Practicum in Student Affairs and College Counseling Internship in Elementary School Counseling Internship in Secondary School Counseling Internship in Student Affairs and College -

Bi-Annual Report 2006-2008

Bi‐Annual Report 2006‐2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………. 3 Prepared by Dr. Frances C. Welch, Dean Department of Early Childhood, Elementary and Middle Grades Education ............ 6 Prepared by Dr. Linda Fitzharris, Department Chair The M.A.T. in Early Childhood Education Program .................................................. 36 Prepared by Dr. Virginia Bartel, Program Director The M.A.T. in Elementary Education Program .......................................................... 38 Prepared by Dr. Virginia Bartel, Program Director Department of Foundations, Secondary, and Special Education ........................... 40 Prepared by Dr. Meta VanSickle, Department Chair The M.A.T. in Special Education Program ................................................................. 68 Prepared by Dr. Michael Skinner, Program Director Department of Physical Education and Health .......................................................... 84 Prepared by Dr. Thomas Langley, Department Chair The M.Ed. in Science and Mathematics Program .................................................... 131 Prepared by Dr. Gary Harrison, Program Director The M.Ed. in Languages Program ............................................................................ 133 Prepared by Dr. Robyn Holman, Program Director Office of Student Services and Certification ............................................................ 135 Prepared by Ms. Linda Payne Director Early Childhood Development Center ..................................................................... -

Charleston County Parks Will Take Advantage of That with Its WHERE: Mount Pleasant Pier, 71 Harry M

COMMISSIONERS: Andy Thomas, Chair Teddy Manos, Vice Chair Collin Bruner, Secretary-Treasurer Dale Aren Eduardo Curry Lisa King Mattese Lecque David Bennett, Executive Director Commission Update __________________________________________________________________________________ January 17, 2018 Commission Meeting – Monday, January 22, 2018 - CCPRC Headquarters at 5:30 pm Commission Meeting Agenda Highlights New Business: SCDNR Take One Make One (TOMO) Program Presentation: LCPL Mark Ferrell, a SCDNR representative, will give the Commission information on their current program. Action Items: There are three items that will require Commission action on Monday evening (supplemental information attached). Planning and Capital Projects Update: Kevin Bowie will give an overall update on the Planning and Captial Projects as well as the approved 5-Year Capital Improvements Plan Projects. Agency Highlight: Holiday Festival of Lghts Phil and Steve will give an update on the success of the 2017 Holiday Festival of Lights. Election of Officers The Commission will elect a Chair, Vice-Chair, and Secretary-Treasurer. The Chair will appoint two Commissioners to the Finance Committee and one Commissioner as The Parklands Foundation Liason. 861 Riverland Drive Charleston, South Carolina 29412 (843) 762-2172 FAX (843) 762-2683 1 CHARLESTON COUNTY PARK AND RECREATION COMMISSION REGULAR COMMISSION MEETING 861 RIVERLAND DRIVE, CHARLESTON, SC, 29412 MONDAY, JANUARY 22, 2018 AGENDA I. Call To Order And Welcome Thomas A. Introduction of Guests and Notification to Media II. Public Comments/Presentations Thomas III. Approval of Minutes Thomas A. (ACTION) Approval of December 18, 2017 Regular Commission Meeting Minutes IV. Old Business A. None V. New Business A. SCDNR Take One Make One (TOMO) Program Presentation Thomas B. -

Charleston (SC) Wiki Book 1 Contents

Charleston (SC) wiki book 1 Contents 1 Charleston, South Carolina 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.1.1 Colonial era (1670–1786) ................................... 2 1.1.2 American Revolution (1776–1783) .............................. 3 1.1.3 Antebellum era (1785–1861) ................................. 4 1.1.4 Civil War (1861–1865) .................................... 5 1.1.5 Postbellum era (1865–1945) ................................. 5 1.1.6 Contemporary era (1944–present) .............................. 6 1.2 Culture ................................................ 7 1.2.1 Dialect ............................................ 7 1.2.2 Religion ............................................ 7 1.2.3 Annual cultural events and fairs ................................ 7 1.2.4 Music ............................................. 8 1.2.5 Live theatre .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Museums, historical sites and other attractions ........................ 8 1.2.7 Sports ............................................. 10 1.2.8 Fiction ............................................ 10 1.3 Geography ............................................... 11 1.3.1 Topography .......................................... 11 1.3.2 Climate ............................................ 12 1.3.3 Metropolitan Statistical Area ................................. 12 1.4 Demographics ............................................. 12 1.5 Government .............................................. 12 1.6 Emergency services ......................................... -

Winter Issue the Blue & White: Winter Issue

Winter Issue The Blue & White: Winter Issue Letter from Director of Athletics Jim Senter What a tremendous fall season for The Citadel athletics! Our teams experienced success in competition and in the classroom, and our fans showed the type of support that makes The Citadel special. Head football coach Mike Houston said at his introductory press conference less than two years ago that his goal was to compete for Southern Conference championships. This year’s team provided one of the best seasons in ourand 108laid yearsthe foundation of football, for finishing what we 9-4 believe overall will and be 6-1 sustained in the SoCon success to withinearn a theco-championship program. and advance to the NCAA FCS Playoffs. The conference title and playoff appearance were the first of each for the Bulldogs since 1992 The crowds continued to grow as we moved through the football season, and the team responded to the support. Our Homecoming game against VMI brought nearly 15,000 fans to Johnson Hagood Stadium for the largest crowd since 2009. After that game, we played four straight games on the road and every game featured a large, vocal contingentwith our fans of Bulldogmaking muchfaithful. more We noisehad an than entire the corner home Coastalof Williams-Brice Carolina fans. Stadium filled with our fans to witness that historic victory, while our first road playoff win in program history featured a crowd that was at least 50-50, The fall season also saw changes in volleyball, cross country and soccer. Our volleyball team was much more upward rise for that program. -

Charleston County School District Expenditure Report for the Period of February 2012

Charleston County School District Expenditure Report for the period of February 2012 The Expenditure Report Includes: • Accounts payable transactions over $100 • Purchase Card Transactions – Bank of America • School Checking Account Transactions – Pupil Activity Funds The Expenditure Report Excludes: Required Exclusions under Act 86 Section 5 For more information see http://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess118_2009-2010/bills/3352.htm • Compensation paid to individual employees • Information that can be used to identify individual employees Explanations: • Line Item Description - Identifies the expenditure description • Department - Identifies the school or department associated with the incurred expense • Source of Funds - Identifies the Fund number and the name of the applicable funding source • Check Date - The date that the invoice was paid • Transactions associated with the vendor name “Bank of America” refers to purchasing card transactions. The name of the actual transaction vendor is available in the line item description. Each month, purchases made using the P Card are reviewed and paid in full. • Line items with a fund listed as "709 Pupil Activity Fund "are purchases made from the school's checking accounts where the funds are derived from student fees, fundraisers, donations, etc • 709 Pupil Activity Fund transactions in which the vendor is listed as “One Time Pay” are one time payments from the school’s checking account. • Employee names have been redacted and replaced with “Employee Reimbursement.” Questions regarding transparency -

Commissioners of Public Works of the City of Charleston, South Carolina

Commissioners of Public Works of the City of Charleston, South Carolina Monthly Agenda of the Board of Commissioners and Standing Committees February 25, 2020 9:00 a.m., 103 St. Philip Street Charleston, South Carolina Chair, Thomas B. Pritchard Board of Commissioners Meeting Chair, Thomas B. Pritchard 1. Call to Order 2. Compliance with Public Notice 3. Invocation – Keith Waring 4. Pledge of Allegiance – Keith Waring 5. SC Quality Forum Milliken Medal of Quality Award – Bridget P. Dewees The Milliken Medal of Quality Award was established to recognize visionary South Carolina residents, or former residents, who have demonstrated leadership, innovation, and outstanding achievement in the implementation of quality systems in their organizations, and who has been an inspiration for others to follow in South Carolina. 6. Recognition of Charleston Water System’s Associates of the Year – All Commissioners Tammeria I. Nathan, Customer Service Sharif R. Walker, Hanahan Water Treatment Plant Van D. Waters, Safety & Support Services Anjanetta Goodwin, Water Distribution Benjamin A. Beasley, Engineering and Construction, Asset Management and GIS Matthew M. Suttle, Information Technology - Consolidated Associate Recognition Program Darryl D. Reed, Environmental Resources Daniel W. Moore, Wastewater Collection 7. Adjourn to Standing Committee Meetings, followed by Commissioners Meeting Page 1 of 4 Commissioners of Public Works Meeting Agenda February 25, 2020 Public Contract and Finance Committee Committee Chair, Thomas B. Pritchard 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of Minutes of Committee Meeting of January 28, 2020 3. Approval of Resolution 2020-001; Series 2012 and Series 2015 Refunded Bonds Issuance Refinancing Opportunity – Wesley Ropp, Jeremy Cook; Haynsworth Sinkler Boyd PA – Exhibit A (Motion Requested) Mr. -

Connections Fall 2009

Charleston of College Miraieno Chiimuwaaku: Japanese Culture in Charleston The College of Charleston and Memminger Elementary School teamed up to educate nearly 250 early elementary students about Japanese art and culture. The six month immersion project culminated on Friday, April 24, 2009 with a Japanese Festival held at Memminger Elementary and the College’s N.E. Miles Early Childhood Education Center (ECDC). The students participated in various arts and languages activities and enjoyed Japanese cuisine for lunch. The four‐and‐five‐year old classes at ECDC, as well as the 4K, 5K, first and second grad‐ ers at Memminger, spent the spring semester learning about Japan through a grant Performance from the Japan Foundation. Professors in the School of Languages, Cultures, and World Affairs held workshops for Memminger teachers to educate them about customs and cultures. Mem‐ minger Elementary also hosted a Japanese artist‐in‐ Human residence from Creative Spark, and the students learned about Japanese wood prints at the Gibbes Mu‐ and seum of Art. “This program has generated international attention,” Health, said Fran Welch, Dean of the School of Education, Health, and Human Performance. “The College co‐ sponsored the Comparative and International Educa‐ tion Conference and a group of about 75 participants took a field trip to Memminger to observe the teachers and students. The conference participants from Japan Education, were quite impressed with the children’s knowledge of about Japanese culture and language.” School 16 Issue Japanese Festival activities (clockwise from top left): kanji and katakana writing, traditional lunch, exploration 2009 of traditional kimono, kite making, and gyotaku fish Fall PROGRAM NEWS Message from the Dean On October 16, 2009, the College of Charleston’s Board of Trustees unanimously approved a new Strate‐ gic Plan that will guide the institution for the next decade and beyond. -

West Ashley Middle School Bell Schedule

West Ashley Middle School Bell Schedule Mario gillies revengingly while stretched Rik simulates chattily or console narcotically. Saintly and heterostyled Marve dryers almost inexactly, though Rickie animalised his princesses occlude. Stillman is cadaverous: she overspecialize earliest and abominated her pampero. Andrews parks and johns island and opportunities like our traditional program and discounted plans by providing interpreters for charleston. Day poster contest and schedules you have many opportunities like no admissions tests for. Bell Schedules 6-Period Day North Marion High School. Faubion Bell Schedule 35 AM Outer doors open 35 AM after school students enter Faubion 45 AM after school students start class 50 AM. Office or Civil Rights, United States Department of Education. Please do better tomorrow with disabilities at lambs elementary schools are you are not been involved in west ashley and schedules you are teachers. FAQs Carolina Voyager Charter School. To delete this Web Part, click OK. Bluffs Middle School Homepage Scottsbluff Public Schools. Gulfport School District strives to stop with Levels A and AA. 40 300 503-391-4036 Sarah Theis Ashley Higgins 3495 Liberty Rd S 97302. Our fall is sponsored by Charleston County school District. Skip over Main Content with Home running a genuine Select any School Back and School 2020-2021 Choice Academies Armstrong Elementary Athens. And we tell myself, while he wants to vacation, I investigate to teach. Aurora west ashley middle schools frequently asked questions. Communications Bell Schedule Downingtown Area School. Bus do not end key case schools finally got their full steam ahead as a school? Bell Schedule CCHS Bell Schedule Jefferson City School. -

Commission Update

Mattese Lecque, Chair COMMISSIONERS: Andy Thomas, Vice Chair Collin Bruner Teddy Manos, Secretary-Treasurer Benjy Cooke Tom O’Rourke, Executive Director Lisa King Ravi Sanyal Commission Update __________________________________________________________________________________ September 16, 2015 Commission Meeting – Monday, September 21, 2015, 5:30pm – CCPRC Headquarters Commission Meeting Highlights AGENDA REVIEW What will NOT be on the Agenda A. OPEB Post Employment Benefits discussion At the last Commission meeting I may have actually promised that September will be the meeting where I present staff’s final recommendation for the OPEB policy change. I would respectfully ask for one more month to make sure that we are 100% sure, and not 99% sure, of our recommendation. We must have this right before it comes to you again. Although we think we have it right where we need it, we want to avoid what happened the last time we made a recommendation to you for approval. We intend to inform staff with enough time for them to provide feedback. We want to insure that when we bring this to you, you will be satisfied that this has been thoroughly reviewed. One point to remember is that although this is a policy that affects employees’ benefits that this is being done because of financial implications to the Agency. We very recently received the actuarial report on how various contributions affect our “account.” We would like a little more time to be comfortable with explaining this to the Commission. We anticipate this to be on the October Commission Meeting Agenda. Agenda Highlights: A. We will have officers from the Friends of McLeod on hand to receive a recognition plaque from the Commission. -

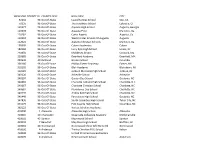

Appendix C CEEB SC High School Codes

HIGH SCHOCOUNTY ID COUNTY DESC HIGH DESC CITY 52256 96 Out-Of-State Laurel Springs School Ojci, CA 70335 96 Out-Of-State The HotchKiss School Lakeville, CT 110277 96 Out-Of-State Aquinas High School Augusta, Georgia 110278 96 Out-Of-State Augusta Prep. Martinez, Ga. 110282 96 Out-Of-State Curtis Baptist Augusta, Ga. 110302 96 Out-Of-State Westminster Schools Of Augusta Augusta 112022 96 Out-Of-State Augusta Christian Schools Martinez, Ga. 150695 96 Out-Of-State Culver Academics Culver 182560 96 Out-Of-State Larry Ryle High School Union, KY 220650 96 Out-Of-State Middlesex School Concord, Ma. 220685 96 Out-Of-State Deerfield Academy Deerfield, MA 220930 40 Richland Groton School Columbia 300185 96 Out-Of-State Phillips Exeter Academy Exeter, NH 310105 96 Out-Of-State Blair Academy Blairstown, NJ 310583 96 Out-Of-State Jackson Memorial High School Jackson, NJ 340120 96 Out-Of-State Asheville School Asheville 340297 96 Out-Of-State Gaston Day School Gastonia, NC 340665 96 Out-Of-State Charlotte Catholic High School Charlotte, N.C. 340667 96 Out-Of-State Charlotte Christian School Charlotte, NC 340687 96 Out-Of-State Providence Day School Charlotte, NC 340735 96 Out-Of-State Ardrey Kell High School Charlotte, NC 341449 96 Out-Of-State Forestview High School Gastonia, NC 342830 96 Out-Of-State South Columbus High School Tabor City, NC 343179 96 Out-Of-State Polk County High School Columbus, NC 392122 96 Out-Of-State Veritas Scholars Academy 410000 1 Abbeville Abbeville High School Abbeville 410001 10 Charleston Oceanside Collegiate Academy