Ritual, Reading and Resistance in the Prison and Cowshed During The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dangerous Truths

Dangerous Truths The Panchen Lama's 1962 Report and China's Broken Promise of Tibetan Autonomy Matthew Akester July 10, 2017 About the Project 2049 Institute The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. Located in Arlington, Virginia, the organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region-specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. About the Author Matthew Akester is a translator of classical and modern literary Tibetan, based in the Himalayan region. His translations include The Life of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, by Jamgon Kongtrul and Memories of Life in Lhasa Under Chinese Rule by Tubten Khetsun. He has worked as consultant for the Tibet Information Network, Human Rights Watch, the Tibet Heritage Fund, and the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, among others. Acknowledgments This paper was commissioned by The Project 2049 Institute as part of a program to study "Chinese Communist Party History (CCP History)." More information on this program was highlighted at a conference titled, "1984 with Chinese Characteristics: How China Rewrites History" hosted by The Project 2049 Institute. Kelley Currie and Rachael Burton deserve special mention for reviewing paper drafts and making corrections. The following represents the author's own personal views only. TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Image: Mao Zedong (centre), Liu Shaoqi (left) meeting with 14th Dalai Lama (right 2) and 10th Panchen Lama (left 2) to celebrate Tibetan New Year, 1955 in Beijing. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Curriculum Vitae for RICHARD L

Richard L. Davis, CV Curriculum Vitae for RICHARD L. DAVIS 戴仁柱 Office Department of History, Lingnan University Address: 302 Ho Sin Hang Bldg., Tuen Mun, NT Hong Kong tel. 852-2616-7007; fax 852-2467-7478 Home: Apt. G, F-18, Tower 1, 8 Waterloo Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong tel. 852-3486-2918 e-mail: [email protected] Date of Birth: April 12, 1951 Buffalo, New York, USA EDUCATION Ph.D.: 1980, Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department Major field of concentration: Tang-Song (A.D. 618-1279) political and cultural history (劉子健 James T.C. Liu, advisor) Minor fields of concentration: Yuan-Ming (A.D. 1271-1644) cultural history (Frederick W. Mote advisor) and modern Chinese politics (Lynn White III advisor) Dissertation: “The Shih Lineage at the Southern Sung Court: Aspects of socio-political mobility in Sung China” M.A.: 1977, Princeton University, East Asian Studies Department M.A.: 1975, State University of New York at Buffalo, History Department B.A.: 1973, State University of New York at Buffalo, Political Science and Asian Studies double major Non-degree Fall 1977-Spring 1979, Academia Sinica (Taipei), Institute of History Programs: & Philology, visiting research fellow 中央研究院/史語所 Summer 1973-Summer 1974, National Taiwan Normal University, 2 CV for Richard L. Davis Mandarin Training Center, post-graduate language training 國立台灣師範大學/國語中心 Summer 1976, Middlebury College, intensive Intermediate Japanese Summer 1972, Stanford University, intensive Classical Chinese Languages: Modern Chinese – fluency in reading and speaking Classical Chinese -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

An Analysis of Chao Jiong's Conception of the Three Teachings

chao jiong’s three teachings douglas skonicki Getting It for Oneself: An Analysis of Chao Jiong’s Conception of the Three Teachings and His Method of Self-Cultivation fter retiring from office in 1026, the Northern Song literatus Chao A 5Jiong 晁迥 (951–1034) chose to devote the remaining years of his life to reading, contemplation, and self-cultivation. Isolating himself within his family compound in the capital, Chao engaged in rigorous textual study, gymnastic exercises, and various forms of meditation that were designed to prolong his life, calm his mind, and facilitate his realization of the Dao. Chao eschewed rigid sectarianism and he utilized the teachings and practices of Buddhism, Daoism, and Con- fucianism to help him realize these objectives. Furthermore, he wrote about his post-retirement activities in detail, penning three separate texts in which he recorded his observations on the Three Teachings, the term traditionally used to refer to those three major practices, and their utility in furthering his efforts to cultivate the self. Chao’s texts — Zhaode xinbian 昭德新編 (New Compilation from Zhaode), Fazang suijin lu 法藏碎金錄 (Record of Golden Fragments from the Buddhist Canon), and Daoyuan ji 道院集 (The Daoist Cloister Collection) — contain a wealth of material on his conception of the Three Teachings and their methods of practice. As the most detailed and comprehensive literati statement on these matters surviving from the early Song, Chao’s works consti- tute an invaluable source for understanding early-Song approaches to the Three Teachings and self-cultivation. Yet, despite the intrinsic interest of these works and their po- tential to shed light on the early Song intellectual milieu, they have not attracted much scholarly attention. -

Prepared Statement of Xiaorong Li, Independent Scholar

Prepared Statement of Xiaorong Li, Independent Scholar Congressional-Executive Commission on China Roundtable on "Current Conditions for Human Rights Defenders and Lawyers in China, and Implications for U.S. Policy" June 23, 2011 The serious backsliding of the Chinese government’s human rights records had started before the 2008 Summer Olympics, highlighted with the jailing of activists Hu Jia, Huang Qi, and many others, the torture and disappearance of lawyer Gao Zhisheng, the imprisonment of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo and house arrest of his wife, both incommunicado, and the house arrest of Chen Guangcheng after his release. Yesterday’s release of the artist Ai Weiwei on bail awaiting for trial was in the same fashion as his arrest: with disregard of the Chinese law. All these took place in the larger context of severe restrictions on freedom of expression and association, repression against religious and ethnic minorities, and significant roll-back on rule of law reform. Since February, several hundreds of people have been harassed or persecuted in one of the harshest crackdowns in recent years when the Chinese government tried to stamp out any sparks for protests in the Tunisia-style “Jasmine Revolution” after online calls first appeared. According to information documented by the group Chinese Human Rights Defenders, the Chinese government has criminally detained a total of 49 individuals, outside the Tibet and Xinjiang regions. As of today, nine of them have been formally arrested, three sent to Re-education through Labor (RTL) camps, 32 have been released but most of them not free: out of which 22 have been released on bail to await trial, while four remain in criminal detention. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1995/34 12 January 1995 Original: ENGLISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fiftieth session Item 10 (a) of the provisional agenda QUESTION OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF ALL PERSONS SUBJECTED TO ANY FORM OF DETENTION OR IMPRISONMENT, IN PARTICULAR: TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT Report of the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Nigel S. Rodley, submitted pursuant to Commission on Human Rights resolution 1992/32 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ....................... 1- 4 4 I. MANDATE AND METHODS OF WORK ............ 5- 24 6 II. INFORMATION REVIEWED BY THE SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR WITH RESPECT TO VARIOUS COUNTRIES ......... 25-921 10 Algeria ...................... 26- 27 10 Angola ....................... 28 10 Argentina ..................... 29- 41 11 Bahrain ...................... 42- 50 12 Bangladesh ..................... 51- 57 14 Belgium ...................... 58- 60 15 Bolivia ...................... 61- 65 16 Brazil ....................... 66- 73 16 Bulgaria ...................... 74- 80 18 Burundi ...................... 81 20 Cameroon ...................... 82- 86 20 Chile ....................... 87- 88 21 GE.95-10085 (E) E/CN.4/1995/34 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page China...................... 89-128 21 Colombia .................... 129-137 27 Côte d’Ivoire ................. 138 29 Croatia..................... 139-140 29 Cuba ...................... 141-149 30 Cyprus ..................... 150-153 31 Czech Republic ................. 154 32 -

Laogai Handbook 劳改手册 2007-2008

L A O G A I HANDBOOK 劳 改 手 册 2007 – 2008 The Laogai Research Foundation Washington, DC 2008 The Laogai Research Foundation, founded in 1992, is a non-profit, tax-exempt organization [501 (c) (3)] incorporated in the District of Columbia, USA. The Foundation’s purpose is to gather information on the Chinese Laogai - the most extensive system of forced labor camps in the world today – and disseminate this information to journalists, human rights activists, government officials and the general public. Directors: Harry Wu, Jeffrey Fiedler, Tienchi Martin-Liao LRF Board: Harry Wu, Jeffrey Fiedler, Tienchi Martin-Liao, Lodi Gyari Laogai Handbook 劳改手册 2007-2008 Copyright © The Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) All Rights Reserved. The Laogai Research Foundation 1109 M St. NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel: (202) 408-8300 / 8301 Fax: (202) 408-8302 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.laogai.org ISBN 978-1-931550-25-3 Published by The Laogai Research Foundation, October 2008 Printed in Hong Kong US $35.00 Our Statement We have no right to forget those deprived of freedom and 我们没有权利忘却劳改营中失去自由及生命的人。 life in the Laogai. 我们在寻求真理, 希望这类残暴及非人道的行为早日 We are seeking the truth, with the hope that such horrible 消除并且永不再现。 and inhumane practices will soon cease to exist and will never recur. 在中国,民主与劳改不可能并存。 In China, democracy and the Laogai are incompatible. THE LAOGAI RESEARCH FOUNDATION Table of Contents Code Page Code Page Preface 前言 ...............................................................…1 23 Shandong Province 山东省.............................................. 377 Introduction 概述 .........................................................…4 24 Shanghai Municipality 上海市 .......................................... 407 Laogai Terms and Abbreviations 25 Shanxi Province 山西省 ................................................... 423 劳改单位及缩写............................................................28 26 Sichuan Province 四川省 ................................................ -

A Chinese Academic on the Hundred Flowers Campaign

SOURCE ANALYSIS CR4/ 02 A CHINESE ACADEMIC ON THE HUNDRED FLOWERS CAMPAIGN A Chinese academic, Wu Ningkun, recalls the Hundred Flowers Campaign: The Central committee enjoined party leaders at all levels to solicit criticism from people in every walk of life, especially from intellectuals and members of “democratic” parties. The critics were urged to “air their views without reserve” for the benefit of the party and its members … We all applauded the courageous decision taken by the party … The People’s Daily and other newspapers in Beijing carried numerous articles by well-known intellectuals criticizing party officials and even the guidelines of the party itself … At meetings at universities and government departments many people poured out their hearts in hopes of helping the party and its members mend their ways…Freedom of speech was having its day; that day was short … The sagacious “Great Leader” let it be known at a later date that all this had been a premeditated plot to “coax a snake out of its lair,” or to ensnare his critics into a trap … I fell into the trap … According to later government statistics, more than half a million people were labeled rightists. There were no figures for those who had been denounced but spared the label, nor of those who had been driven to insanity or suicide. The “hundred flowers” ended in a mass intellectual castration that was to plague the nation for decades to come, putting to shame the notorious emperor of the Han Dynasty who had unjustly punished only one dissident historian with physical castration. -

Do Not Kill the Goose That Lays Golden Eggs: the Reasons of the Deficiencies in China’S Intellectual Property Rights Protection

DO NOT KILL THE GOOSE THAT LAYS GOLDEN EGGS: THE REASONS OF THE DEFICIENCIES IN CHINA’S INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS PROTECTION XIUYI ZHENG MPhil University of York Law March 2015 Abstract China’s intellectual property protection, which has been considered weak and discussed for decades, is playing an increasingly significant role in global trading. In the past decades, China has made great strikes in its intellectual property rights (IPR) protection, while its performance is still not satisfactory, especially in the eyes of developed countries. Before taking any further coercive strategies, both developed countries and China should look into the reasons of the deficiencies in China’s IPR protection so that measures could be taken more efficiently. This thesis will focus on the detailed history of the development of China’s IPR protection with a historical method, thus justifying the theory that late start and slow development are the main two reasons of the deficiencies in China’s IPR system. The concept of IPR did not exist in China until the end of 19th century due to the influence of Confucianism. The weak awareness of IPR lasted till now. From the day that western forces brought the idea of IPR into China to the establishment of a genuine protection system, China experienced a violent social turbulence with many changes in regimes and guiding ideologies. Meanwhile, Chinese government was continuously in the dilemma: whether they should pursuit a better IPR protection system or learn advanced knowledge and technologies from developed countries. All these factors slowed down the development of IPR in China. -

2.17 Shanghai City Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development

2.17 Shanghai City Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development (Group) Co., Ltd., affiliated with the Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration Bureau, has 20 prison enterprises1 Legal representative of the prison company: Mao Guoping, Chairman of Shanghai Shenyue Enterprise Development (Group) Co., Ltd. His official positions in the prison system: Director of Planning and Finance Division of Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration Bureau2 The Shanghai Municipal Prison Administration now administers 11 prisons and one Juvenile Delinquency Reformatory. Among them, the Baimaoling Prison and Juntianhu Prison are located in the Wannan area (i.e. southern part of Anhui Province). There are also the Prison General Hospital, the Judicial Police School and a number of security enterprises that serve the prison-related work. Since 1949, these prisons have accumulatively detained more than 400,000 criminals.3 No. Company Name of the Prison, Legal Person Legal Registered Business Scope Company Address Notes on the Prison Name to which the and representative / Capital Company Belongs Shareholder(s) Title 1 Shanghai Shanghai Municipal Shanghai Mao Guoping 11.846 Industrial investment, Building No. 150, 111 The main responsibilities of the Shanghai Shenyue Prison Municipal million business management, Changyang Road, Municipal Prison Administration Bureau and Chairman of Enterprise Administration Prison yuan financial consulting Shanghai City its staffing are according to the “Notice of the Shanghai Developme Bureau Administration (actually services, commercial General Office of the Chinese Communist nt (Group) Shenyue paid 77.148 activities, domestic Bureau Enterprise Party Central Committee and the General Co., Ltd. million trading Office of the State Council, regarding the Development yuan) (Group) Co., Shanghai Municipal People’s Government Ltd.; Director of Institutional Reform Scheme” (No. -

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps

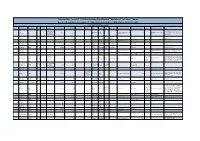

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps Based on Reports Received January - December 2009, Listed in Descending Order by Sentence Length Falun Dafa Information Center Case # Name (Pinyin)2 Name (Chinese) Age Gender Occupation Date of Detention Date of Sentencing Sentence length Charges City Province Court Judge's name Place currently detained Scheduled date of release Lawyer Initial place of detention Notes Employee of No.8 Arrested with his wife at his mother-in-law's Mine of the Coal Pingdingshan Henan Zhengzhou Prison in Xinmi City, Pingdingshan City Detention 1 Liu Gang 刘刚 m 18-May-08 early 2009 18 2027 home; transferred to current prison around Corporation of City Province Henan Province Center March 18, 2009 Pingdingshan City Nong'an Nong'an 2 Wei Cheng 魏成 37 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 18 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2027 Arrested from home; County Court Zhejiang Fuyang Zhejiang Province Women's 3 Jin Meihua 金美华 47 f 19-Nov-08 15 Fuyang City November, 2023 Province City Court Prison Nong'an Nong'an 4 Han Xixiang 韩希祥 42 m Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Nong'an Nong'an 5 Li Fengming 李凤明 45 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Arrested from home; detained until late April Liaoning Liaoning Province Women's Fushun Nangou Detention 6 Qi Huishu 齐会书 f 24-May-08 Apr-09 14 Fushun City 2023 2009, and then sentenced in secret and Province Prison Center transferred to current prison.