Identities Without Borders: June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and the Legacy of Post-Civil Rights Black Feminism David M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: an Argument from Bisexuality

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2012 Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 415 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Liberty and Same-Sex Marriage: An Argument from Bisexuality MICHAEL BOUCAI* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.........................................................416 II. SEXUAL LIBERTY AND SAME-SEX MARRIAGE .............................. 421 A. A Right To Choose Homosexual Relations and Relationships.........................................421 B. Marriage'sBurden on the Right............................426 1. Disciplineor Punishment?.... 429 2. The Burden's Substance and Magnitude. ................... 432 III. BISEXUALITY AND MARRIAGE.. ......................................... -

AAS 310 BLACK WOMEN in the AMERICAS Spring 2016

AAS 310 BLACK WOMEN IN THE AMERICAS Spring 2016 Professor: Place: Day/Time: Office/ Office hours: Course Description: This course presents an interdisciplinary body of scholarship on the social, political, economic, cultural and historical contexts of Black women’s lives in the United States and across the Americas, with a particular focus on Black women’s roles in the development of democratic ideas. We will also focus on the relationship between representations and realities of Black women. One of the central questions we will ask is who constitutes as a black woman? Considering the experiences of mixed-race African American women, Black women in Latin America and the Caribbean, and queer Black women will allow us to consider the ways that race, gender, sexuality and nation operate. Course Objectives: 1. To examine the history, development and significance of Black Women's Studies as a discipline that evolved from the intersection of grassroots activism, "womanist" knowledge and the quest for human rights in a democracy. 2. To examine the terms “Feminist Theory”, “Black Feminist Theory” and “Womanist Theory” as conceptual frameworks for knowledge production about Black women’s lives. 3. To examine “intersectionality” as a critical factor in Black women’s lived experiences in America. 4. To critically analyze stereotypes and images of Black womanhood and the ideologies surrounding these images and to explore the social, political and policy implications of these images. 5. To introduce students to an interdisciplinary body of feminist research, critical essays, prose, fiction, poetry and films by and about Black American women. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. -

Nepantla.Issue3 .Pdf

Nepantla A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color Editor-In-Chief Christopher Soto Manager William Johnson Cover Image David Uzochukwu Welcome to Nepantla Issue #3 Wow! I can't believe this is already the third year of Nepantla's existence. It feels like just the other day when I only knew a handful of queer poets of color and now my whole life is surrounded by your community. Thank you for making this journal possible! This year, we read thousands of poems to consider for publication in Nepantla. We have published twenty-seven poets below (three of them being posthumous publications). It's getting increasingly more difficult to publish all of the amazing poems we encounter during the submissions process. Please do not be discouraged from submitting to us multiple years! This decision, to publish posthumously, was made in a deep desire to carry the legacies of those who have helped shape our understandings of self and survival in the world. With Nepantla we want to honor those who have proceeded us and honor those who are currently living. We are proud to be publishing the voices of June Jordan, Akilah Oliver, and tatiana de la tierra in Issue #3. This year's issue was made possible by a grant from the organization 'A Blade of Grass.' Also, I want to acknowledge other queer of color journals that have formed in the recent years too. I believe that having a multitude of journals, and not a singular voice, for our community is extremely important. Oftentimes, people believe in a destructive competition which doesn't allow for their communities to flourish. -

Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins • Eloquent Rage: a Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Dr

Resource List Books to read: • Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins • Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Dr. Brittney Cooper • Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon • How To Be An Antiracist by Dr. Ibram X. Kendi • I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou • Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson • Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad • Raising Our Hands by Jenna Arnold • Redefining Realness by Janet Mock • Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde • So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo • The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison • The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin • The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander • The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century by Grace Lee Boggs • The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson • Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston • This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color by Cherríe Moraga • When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth Century America by Ira Katznelson • White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo, PhD • Fania Davis' Little Book of Race and RJ • Danielle Sered's Until We Reckon • The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness Films and TV series to watch: • 13th (Ava DuVernay) — Netflix • American Son (Kenny Leon) — Netflix • Black Power Mixtape: 1967-1975 — Available to rent • Blindspotting (Carlos López Estrada) — Hulu with Cinemax or available to rent • Clemency (Chinonye Chukwu) — Available to rent • Dear White People (Justin Simien) — Netflix • Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler) — Available to rent • I Am Not Your Negro (James Baldwin doc) — Available to rent or on Kanopy • If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins) — Hulu • Just Mercy (Destin Daniel Cretton) — Available to rent for free in June in the U.S. -

SPR2013 SOC200 Syllabus DRAFT.Docx

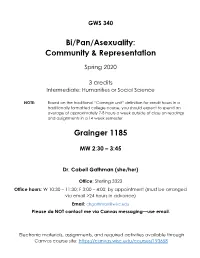

GWS 340 Bi/Pan/Asexuality: Community & Representation Spring 2020 3 credits Intermediate; Humanities or Social Science NOTE: Based on the traditional “Carnegie unit” definition for credit hours in a traditionally formatted college course, you should expect to spend an average of approximately 7-8 hours a week outside of class on readings and assignments in a 14-week semester Grainger 1185 MW 2:30 – 3:45 Dr. Cabell Gathman (she/her) Office: Sterling 3323 Office hours: W 10:30 – 11:30; F 3:00 – 4:00; by appointment (must be arranged via email >24 hours in advance) Email: [email protected] Please do NOT contact me via Canvas messaging—use email. Electronic materials, assignments, and required activities available through Canvas course site: https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/193658 – 2 – Course Description Bisexual/biromantic, pansexual/panromantic, and asexual/aromantic (BPA) people are often denied (full) membership in the "queer community," or assumed to have the same experiences and concerns as lesbian and gay (LG) people and thus not offered targeted programs or services. Recent research has shown a wide variety of negative outcomes experienced by bisexual/biromantic people at much higher rates than LG people, and still barely acknowledges the existence of pansexual/panromantic or asexual/aromantic people. (Although research differentiating pan and bi people is still quite sparse, what exists suggests that systematic differences may exist between these groups, as well.) This course builds on concepts and information covered in Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies (GWS 200). It will explore the experiences, needs, and goals of BPA people, as well as their interactions with the mainstream lesbian & gay community and overlap and coalition building with other marginalized groups. -

The Black Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions

The Kentucky Review Volume 7 | Number 1 Article 3 Spring 1987 The lB ack Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions Margaret B. McDowell University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation McDowell, Margaret B. (1987) "The lB ack Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Black Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions 1ett Margaret B. McDowell ·e H. Telling stories and writing criticism, Eudora Welty says, are "indeed separate gifts, like spelling and playing the flute, and the same writer proficient in both has been doubly endowed, but even and he can't rise and do both at the same time."1 In view of the o: general validity of this observation, it is remarkable that several of the best Afro-American women authors are also invigorating Hill critics. City 6), Notable among them are Margaret Walker, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison. In the breadth of their inquiry, the ~ss, " zest of their argument, and the intensity of their commitment to issues related to art, race, and gender, they exemplify a new vitality that emerged after about 1970 in women's discourse about black literature. -

June Jordan's Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler in Her Poetry, the Late African Am

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 38 (2013): 65-82 “I am she who will be free”: June Jordan’s Transnational Feminist Poetics Julia Sattler In her poetry, the late African American writer June Jordan (1936- 2002) approaches cultural disputes, violent conflicts, as well as transnational issues of equality and inclusion from an all-encompassing, global angle. Her rather singular way of connecting feminism, female sexual identity politics, and transnational issues from wars to foreign policy facilitates an investigation of the role of poetry in the context of Transnational Feminisms at large. The transnational quality of her literary oeuvre is not only evident thematically but also in her style and her use of specific poetic forms that encourage cross-cultural dialogue. By “mapping connections forged by different people struggling against complex oppressions” (Friedman 20), Jordan becomes part of a multicultural feminist discourse that takes into account the context-dependency of oppressions, while promoting relational ways of thinking about identity. Through forging links and loyalties among diverse groups without silencing the complexities and historical specificities of different situations, her writing inspires a “polyvocal” (Mann and Huffmann 87) feminism that moves beyond fixed categories of race, sex and nation and that works towards a more “relational” narration of conflicts and oppressions across the globe (Friedman 40). Jordan’s poetry consciously reflects upon the experience of being female, black, bisexual, and American. Thus, her work speaks from an angle that is at the same time dominant and marginal. To put it in her own words: “I am Black and I am female and I am a mother and I am a bisexual and I am a nationalist and I am an antinationalist. -

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms

Equity by Design: Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Arts Classrooms Mollie Blackburn Mary Catherine Miller Teaching LGBTQ-Themed Literature in English Language Art Classrooms KEY TERMS Equity Assistance Centers (EACs) are charged with providing technical assistance, LGBTQ - The acronym used to represent lesbian, gay, including training, in the area of sex bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning identities and desegregation, among other areas of themes. We recognize that this acronym excludes some desegregation, of public elementary and people, like those who are asexual or intersex, but we aim to secondary schools. Sex desegregation, here, be honest about who gets featured in literature representing sexual and gender minorities. means the “assignment of students to public schools and within those schools without regard Gender - While “sex” is the biological differentiation of being to their sex including providing students with a male or female, gender is the social and cultural presentation full opportunity for participation in all of how an individual self-identifies as masculine, feminine, or within a rich spectrum of identities between the two. Gender educational programs regardless of their roles are socially constructed, and typically reinforced in a sex” (https://www.federalregister.gov/ gender binary that places masculine and feminine roles in documents/2016/03/24/2016-06439/equity- opposition to each other. assistance-centers-formerly-desegregation- Cisgender - An individual who identifies as the gender assistance-centers). This is pertinent to LGBTQ corresponding with the sex they were assigned at birth students. Most directly, students who identify as (Aultman, 2014; Stryker, 2009). By using cisgender to trans or gender queer are prevented from distinguish someone as not transgender, the term “helps attending school because of the transphobia distinguish diverse sex/gender identities without reproducing they experience there. -

Art for Women's Sake: Understanding Feminist Art Therapy As Didactic Practice Re-Orientation

© FoNS 2013 International Practice Development Journal 3 (Suppl) [5] http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx Art for women’s sake: Understanding feminist art therapy as didactic practice re-orientation *Toni Wright, Karen Wright *Corresponding author: Canterbury Christ Church University, Department of Nursing and Applied Clinical Studies, Canterbury, Kent, UK. Email: [email protected] Submitted for publication: 14th January 2013 Accepted for publication: 6th February 2013 Abstract Catalysed through the coming together of feminist theories that debate ‘the politics of difference’ and through a reflection on the practices of art psychotherapy, this paper seeks to illuminate the progressive and empowering nature that creative applications have for better mental health. It also seeks to critically expose and evaluate some of the marginalisation work that is also done within art psychotherapy practices, ultimately proposing a developmental practice activity and resource hub that will raise awareness, challenge traditional ways of thinking and doing, and provide a foundation for more inclusive practices. This paper’s introduction is followed by a contextualisation of art therapy and third wave feminisms, with suggestions of how those can work together towards better praxis. The main discussion is the presentation of a newly developed practitioner activity and resource hub that art therapists can use to evaluate their current and ongoing practice towards one of greater inclusivity and better reflexivity. Finally, in conclusion there will be a drawing together of what has been possible in feminist art psychotherapy, what remains possible, and with further alliances what more could yet be possible. A video that accompanies this paper is available from: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fLLXVGiZQcU. -

Novel Approaches to Negotiating Gender and Sexuality in the Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The olorC Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Selha, A. D., "Distracting the border guards: novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The oC lor Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues" (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 9. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -r Distracting the border guards: Novel approaches to negotiating gender and sexuality in The Color Purple, Nearly Roadkill, and Stone Butch Blues A. D. Selha A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies Major Professor: Kathy Hickok Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1997 1 ii JJ Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of A.D. Selha has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University 1 1 11 iii DEDICATION For those who have come before me, I request your permission to write in your presence, to illuminate your lives, and draw connections between the communities which you may have painfully felt both a part of and apart from. -

Black Feminist Thought

Praise for the first edition of Black Feminist Thought “The book argues convincingly that black feminists be given, in the words immor- talized by Aretha Franklin, a little more R-E-S-P-E-C-T....Those with an appetite for scholarese will find the book delicious.” —Black Enterprise “With the publication of Black Feminist Thought, black feminism has moved to a new level. Collins’ work sets a standard for the discussion of black women’s lives, experiences, and thought that demands rigorous attention to the complexity of these experiences and an exploration of a multiplicity of responses.” —Women’s Review of Books “Patricia Hill Collins’ new work [is] a marvelous and engaging account of the social construction of black feminist thought. Historically grounded, making excellent use of oral history, interviews, music, poetry, fiction, and scholarly literature, Hill pro- poses to illuminate black women’s standpoint. .Those already familiar with black women’s history and literature will find this book a rich and satisfying analysis. Those who are not well acquainted with this body of work will find Collins’ book an accessible and absorbing first encounter with excerpts from many works, inviting fuller engagement. As an overview, this book would make an excellent text in women’s studies, ethnic studies, and African-American studies courses, especially at the upper-division and graduate levels. As a meditation on the deeper implications of feminist epistemology and sociological practice, Patricia Hill Collins has given us a particular gift.” —Signs “Patricia Hill Collins has done the impossible. She has written a book on black feminist thought that combines the theory with the most immediate in feminist practice. -

A Return to 1987: Glenda Dickerson's Black Feminist Intervention” by Khalid Y

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org A Return to 1987: Glenda Dickerson’s Black Feminist Intervention by Khalid Y. Long The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 33, Number 2 (Spring 2021) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2021 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Glenda Dickerson (1945-2012) is often recognized as a pioneering Black woman theatre director.[1] A more expansive view of her career, however, would highlight Dickerson’s important role as a playwright, an adaptor/deviser, a teacher, and as this essay will illustrate, a progenitor of feminist theatre and performance theory. This essay offers a brief rumination on how Dickerson made a Black feminist intervention into feminist theatre and performance theory as she became one of the earliest voices to intercede and ensure that Black women had a seat at the table.[2] Glenda Dickerson’s intervention into feminist theatre and performance theory appears in her critical writings. Accordingly, these essays illustrate her engagement with Black feminist thought and elucidate how she modeled a feminist theatre theory through her creative works. Dickerson, along with other pioneering feminist theatre artists, “reshaped the modern dramatic/theatrical canon, and signaled its difference from mainstream (male) theatre.”[3] Dickerson’s select body of essays prompted white feminist theorists and practitioners to be cognizant of race and class as well as gender in their work and scholarship.[4] Moreover, Dickerson’s writings serve a dual function for readers: first, they offer an entryway into her life and creative process as a Black feminist artist. Secondly, they detail her subjective experiences as a Black woman within the professional worlds of theatre and academia.