CHAPTER—8 Parliamentary Privileges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Misuse of Electorate Office Staffing Entitlements

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Legislative Council Privileges Committee Inquiry into matters relating to the misuse of electorate office staffing entitlements Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Privileges Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2018 PP No 433, Session 2014‑18 ISBN 978 1 925703 64 1 (print version) 978 1 925703 65 8 (PDF version) Committee functions The Legislative Council Privileges Committee is established under Legislative Council Standing Orders Chapter 23 — Council Committees, and Sessional Orders. The Committee’s functions are to consider any matter regarding the privileges of the House referred to it by the Council. ii Legislative Council Privileges Committee Committee membership Mr James Purcell MLC Ms Nina Springle MLC Chair* Deputy Chair* Western Victoria South‑Eastern Metropolitan Hon. Philip Dalidakis MLC Mr Daniel Mulino MLC Mr Luke O’Sullivan MLC Southern Metropolitan Eastern Victoria Northern Victoria Hon. Gordon Rich-Phillips MLC Ms Jaclyn Symes MLC Hon. Mary Wooldridge MLC South‑Eastern Metropolitan Northern Victoria Eastern Metropolitan * Chair and Deputy Chair were appointed by resolution of the House on Wednesday, 23 May 2018 and Tuesday, 5 June 2018 respectively. Full extract of proceedings is reproduced in Appendix 2. Inquiry into matters relating to the misuse of electorate office staffing entitlements iii Committee secretariat Staff Anne Sargent, Deputy Clerk Keir Delaney, Assistant Clerk Committees Vivienne Bannan, Bills and Research Officer Matt Newington, Inquiry Officer Anique Owen, Research Assistant Kirra Vanzetti, Chamber and Committee Officer Christina Smith, Administrative Officer Committee contact details Address Legislative Council Privileges Committee Parliament of Victoria, Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE, VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2869 Email [email protected] Web http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/lc‑privileges This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

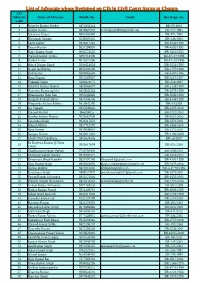

List of Advocate Whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No

List of Advocate whose Registred on CIS in Civil Court Saran at Chapra CIS Advocate Name of Advocate Mobile No. Email Bar Regn. No. Code 1 Birendra Kumar Pandey 9470481114 BR-55/1992 2 Gunjan Verma 9934921847 [email protected] BR-733/1993 3 Mazharul Haque 9905403496 BR-883/1993 4 Bholanath Sharma 9546907435 BR-346/1994 5 Sunil Kumar 9835611348 BR-5740/1995 6 Pawan Kumar 9631594900 BR-4363/1995 7 Rajiv Kumar Singh 8002574542 BR-5310/1995 8 Pramod Kumar Verma 8651814306 BR-10127/1996 9 Pankaj Verma 9835075266 BR-10128/1996 10 Ashok Kumar Singh 9304014624 BR-2631/1996 11 Gopal Jee Pandey 9852088205 BR-2177/1996 12 Kishun Rai 9097962645 BR-8407/1996 13 Renu Kumari 9835268997 BR-3317/1997 14 Tripurari Singh 8292621173 BR-316/1997 15 Birendra Kumar Sharma 8409066877 BR-2124/1998 16 Narendra Kumar pandey 9430945334 BR-3879/1999 17 Dharmendra Nath Sah 9905266646 BR-6243/1999 18 Durgesh Prakash Bihari 9431406306 BR-4144/1999 19 Bhupendra Mohan Mishra 9430945395 BR-68/2009 20 Jay Prakash 9835649645 BR-2397/2010 21 Praveen Kumar 966194025 BR-3132/2003 22 Kundan Kumar Sharma 9525661909 BR-2023/2002 23 Satyendra Singh 9934217633 BR-2870/2001 24 Rakesh Milton 8507718379 BR-1861/2005 25 Ajay Kumar 9939849041 BR-1372/2001 26 Sanjeev Kumar 9430011002 BR-1196/2000 27 Shashi Nath Upadhyay 9430624506 BR-26/1999 Dr Rajeewa Kumar @ Pintu 28 9835617674 BR-951/2000 Tiwari 29 Shashiranjan Kumar Pathak 7739791080 BR-3590/2001 30 Mritunjay Kumar Pandey 9835843533 BR-3316/2003 31 Dineshwer SIngh Kaushik 9931807349 [email protected] BR-4761/1999 32 Ajay -

1 Parliamentary Privilege and the Common Law of Parliament

Parliamentary privilege and the common law of parliament: can MP’s say what they want and get away with it? Carren Walker1 Introduction Parliamentary privilege can be broadly defined as the powers, rights and immunities of parliament and its members. The privileges enjoyed by the parliament are linked historically to the privileges of the UK House of Commons which have their origin in the procedures of the Parliament of Westminster: ..to be found chiefly in ancient practice, asserted by Parliament and accepted over time by the Crown and the courts of law and custom of Parliament.2 The privileges of parliament are defined by the rulings of each House in respect of its own practices and procedures when a matter of privilege arises. The use of the terms ‘history’, ‘procedure’, and ‘tradition’ give the impression of uncertainty, and make those in the legal profession feel most uneasy. The legal world is inhibited by statute, rules, forms and precedent, surrounded by the cocoon of the common law as developed by the courts. Parliamentary privilege and the development of the common law of parliament is based on different principles to those of the common law as developed by the courts. It certainly bears little resemblance in its form and structure to legal professional privilege. The privileges of parliament have changed over time, some are simply not relevant in our modern parliamentary democracy (such as freedom of members from arrest), others (such as the power to detain a person in breach of the privilege) have fallen out of use. These privileges tend to develop as the need arises in a particular House. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Endangering Constitutional Government

Endangering Constitutional Government The risks of the House of Commons taking control Sir Stephen Laws and Professor Richard Ekins About the Authors Sir Stephen Laws KCB, QC (Hon) is a Senior Research Fellow at Policy Exchange, and was formerly First Parliamentary Counsel. Professor Richard Ekins is Head of Policy Exchange’s Judicial Power Project, Associate Professor, University of Oxford. Policy Exchange Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Registered charity no: 1096300. Trustees Diana Berry, Pamela Dow, Alexander Downer, Andrew Feldman, Candida Gertler, Patricia Hodgson, Greta Jones, Edward Lee, Charlotte Metcalf, Roger Orf, Andrew Roberts, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Peter Wall, Nigel Wright. 2 – Endangering Constitutional Government Executive summary The UK’s political crisis is at risk of becoming a constitutional crisis. The risk does not arise because the constitution has been tried and found wanting. Rather, the risk arises because some MPs, with help from the wayward Speaker, are attempting to take over the role of Government. -

Imprisonment for Contempt: Are the Penal Powers of Parliament Compatible with the Rule of Law? I

IMPRISONMENT FOR CONTEMPT: ARE THE PENAL POWERS OF PARLIAMENT COMPATIBLE WITH THE RULE OF LAW? Daniel Matthew Harrop This thesis is presented for the Honours degree of Bachelor of Laws of Murdoch University 2014 I, Daniel Matthew Harrop, declare that this is my own account of my research. 17,302 words D Harrop (2014) Imprisonment for Contempt: Are the Penal Powers of Parliament Compatible with the Rule of Law? i “No man is punishable or can be lawfully made to suffer in body or goods except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary courts of the land.” - A V Dicey D Harrop (2014) Imprisonment for Contempt: Are the Penal Powers of Parliament Compatible with the Rule of Law? ii Copyright Acknowledgment I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s51.2 of the Copyright Act 1968, all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such a reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: _________________________________ Full name of degree: Bachelor of Laws with Honours Thesis title: Imprisonment for Contempt: Are the Penal Powers of Parliament Compatible with the Rule of Law? Author: Daniel Matthew Harrop Year: 2014 D Harrop (2014) Imprisonment for Contempt: Are the Penal Powers of Parliament Compatible with the Rule of Law? iii Abstract The rule of law is synonymous with political legitimacy. -

THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION: CAN MUSLIMS -BE SECULAR? by M

Vcd. XV, No. 3;. CONTENTS 1\iay 1, 1967 .: 1 • •\ .. ~· ' .. Page ), . t;JTQ,li'IAi. · . f . f lli Th~ Our Day. ::_ l"· ~ .... '.. ;. .,, 18 ~ ~~ I .• ~ -· i;:Jeet Subba Rao And Clean Up the Jtlesa By Le~;~ M,artin. · \ . \ The ·Tamil Contribution To Indian CDI~ure. 5 The Economics of Scarcity. u Ranganatlwn. By A. By Herbert C. Roseman. The Presidential Election : Can.. , Muslims...... Be ; · ~ecu~ar?: . · · "'· ,Revalue The Rupee ! 16 By M. ~. Thowl. By Shrhnali Tarke$hwari Sinl•a. M. P.' .. DELHI LE"I:TER .• A Review Of Devaluatioil Of Tbe Rupee, 18 Parity With A Vengeance,... 9. ~· By Prof. M•. R. Hazaray. • .EDITORIAL I ··EI~:d:. Sul>ba'Rao A~d; Clean Up The ·Mess·· .. ·· p RESIDENT Radhakrishnnn rendered a great ser- leaders suggested the ~-election of Dr. Radhn- . vice to the country by his famous speech of Jan- krishnan as the President and Dr. Zakir Husain as uary .2nd in which he focussed serious attention of .Vice-President. But Dr. · Radhakrishnan appears his countrymen on 'the great iness', the Congress .to have weaned Mrs. mdira Gandhi, the Prime ;rl}lers .have made of' our country, .The ·Speech ,went ·Minister, away from hims.el£, by his outspoken· cri- .. heme to the rulers, only to make ,them more deter- :ticism of the Congress rule. 'Mrs. GandhL took this mined to pursue their disastrous policies domestic lcriticism as a personal slight to her and as an un and foreign, in face of the tormenting experience the :complimentary reBection on her administration, not cohn try bas .to pass .through, and to persist in their realising the full implications of D.r. -

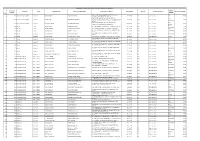

Bihar Shikshak Niyojan 2019-20 Gram Panchayat Raj - Sonmati, Block - Babubarhi,District - Madhubani Class 1 to 5 Combined Provisional Merit List S.No

Bihar Shikshak Niyojan 2019-20 Gram Panchayat Raj - Sonmati, Block - Babubarhi,District - Madhubani Class 1 to 5 Combined Provisional Merit List S.No. Application No. Applicant's Name Father's Name Residential Address Date Of Birth Sex Category Metric Intermedi Training Average TET % Weight Total Merit CTET Enrollment Remarks % ate % % % age Marks /BTE T 1 B-210 Pratibha Kumari Kamal Prasad Mahto Sonpati, Babubarhi 07.03.1999 Female UR 81.7 77 81 79.8 68 2 81.8 CTET 13004037 D.led 2 G-1542 Pandav Thakur Ram Kisan Thakur Phoolkaha, Jaynagar 05.02.1987 Male UR 76.29 72.8 87.18 78.75 60.54 2 80.75 Grade Card is not there 3 B-191 Jyoti Dinesh Kumar Pandit Gadha, Ladaniyan 10.05.1996 Female EBC 74.1 84.4 69.9 76.13 71.33 4 80.13 CTET 15000414 D.led 4 B-21 Sneha Ananad Birendra Prasad Singh Satghara, Babubarhi 14.09.1995 Female UR 81.4 71.4 79 77.26 66 2 79.26 CTET 106070923 D.led 5 P-41 Sudha Devi Vimleshwar Prasad Yadav Hariraha, Laukahi 01.02.1986 Female BC 82.71 75.4 68.87 75.66 56.6 2 77.66 CTET O801733 D.led 6 B-371 Kumari Tushta Rajkumar Yadav Nandnagar, Chakdah, Madhubani 13.03.1993 Female UR 67 78.2 79.3 74.83 60 2 76.83 BTET 6202171302 D.led 7 P-223 Nibha Kumari Pradeep Kumar Singh Paroriyahi, Gajhara 07.07.1997 Female UR 69.6 73.4 81.38 74.79 61.33 2 76.79 CTET 202006198 D.led 8 B-364 Durga Kumari Tej Narayan Chaudhary Devhaar, Andhratharhi 19.12.1994 Female UR 75 62.6 83.3 73.63 62.66 2 75.63 CTET 106065219 B.ed 9 G-1578 Anokha Kumari Raaslal Kamat Naajirtol, Ladaniyan 28.10.1993 Female EBC 61.2 71.6 88.06 73.62 62.59 2 75.62 TET -

A Reconnaisance of Panchayat Election in Bihar

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.8 SUBALTERN RESURGENCE: A RECONNAISANCE OF PANCHAYAT ELECTION IN BIHAR Shaibal Gupta Asian Development Research Centre (ADRI) Patna, India January 2002 Copyright © Shaibal Gupta, 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme Subaltern Resurgence: A reconnaissance of Panchayat election in Bihar Shaibal Gupta Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI), Patna, India The decision of the British Council to wind up its cute library from Patna and surfacing of a new social composition, as revealed in the recently held Panchayat Election in Bihar, probably hold promise of a unique political, academic and cultural potboiler in the firmament of this state. If the British Council Library was the last citadel of Eurocentric world view, the social constellation which has emerged out of the Panchayat election, will be the final triumph of a Bihar-centric rural world view. The chasm between these two world views was being witnessed for a long time; but with the decision of the banishment of the library from this benighted state and further democratization and electoral empowerment through the recent Panchayat Election, there will now be a symbolic breach in the dialogue between these two world views. -

S .No. Application Number Panchayat Block Candidate Name Father's

Madhubani District-Revised List of Shortlisted Candidates of Uddeepika Application DD/IPO Panchayat Block Candidate Name Father's/ Husband Name Correspondence Address Date Of Birth Ctageory Permanent Address Percentage Of Marks Number Number S .No. PANCHAYAT-DAHIBAT MADHOPUR WEST, VILL+PO- 4906 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul BIBHA KUMARI KAILASH PASWAN 13-Feb-86 SC Same as above 00 46.00 1 SALEMPUR, PS-PANDAUL, PIN-847234 PANCHAYAT-DAHIBHAT MADHOPUR WEST, VILL- 71G 3496 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul MANJU DEVI CHANDRAMOHAN RAY MADHEPURA, P.O- D NATHWAN, DIST- MADHUBANI, PIN- 15-Feb-89 GEN Same as above 61.00 916592-93 2 847234 PANCHAYAT-DAHIBHAT MADHEPUR WEST, VILL- 39H 4825 Ahiwat Madhopur(West) Pandaul SUCHITA KUMARI JITENDRA KUMAR RAY 01-Nov-84 GEN Same as above 59.00 3 MADHEPURA, P.S- PANDAUL, PIN- 847234 346021 80G 4882 Akahri Ladania PUNITA DEVI BISHNU KANT ROY VILL- JHITKIYAHI, P.O- AKHARI, P.S- LADNIYA, PIN- 847232 16-Aug-90 EBC Same as above 55.00 4 722702-01 5 4013 Akahri Ladania RINKEE KUMARI PRADEEP KUMAR SAHNI VILL-PARSAHI, PO-SIDHAP, PS-LADANIA, PIN-847232 03-Jun-89 EBC Same as above 39H 59.00 VILL+P.O- AKRAHI, VIA- LADHNIYA, P.S- LADHNIYA, PIN- 816 Akahri Ladania RITA KUMARI BHARAT LAL RAY 05-Mar-90 EBC Same as above 7H 195984 63.00 6 847232 VILL- KESHULI, PO- AKAUR, PS- BENIPATTI, PINCODE- 1926 Akaur Benipatti BHAWANI DEVI MITHILESH KAMAT 11-Jan-85 EBC Same as above 2H 115821 66.00 7 847230 8 1510 Akaur Benipatti KIRAN KUMARI NAWAAL KISHOR YADAV VILL- KESHULI, P.O- AKAUR, P.S- BENIPATTI, PIN- 847230 08-Jan-81 BC Same as -

I'8cj.I8sl the G9vemment to Lat [Translation) This August House Know the Steps It Is Going to Take to Solve Water Crisis in Deihl

403 WlttenAnstNtS APRIL 10,1992 WritrenAnswers 404 would Ike to I'8CJ.I8Sl the G9vemment to lat [Translation) this august House know the steps It Is going to take to solve water crisis in Deihl. This Is SHRI BRISHIAN PATEL: He has been not the problem merely In those areas where arrested. Arrests have been made. They the hon. Mermers of Par1Iament or the Min- hav~ been nabbed. * is related to the leader isters live, but for the common man who face of the opposition in Bihar, Dr Jagannath the water problem. The Goveml'l'J8nt should Mishra. Because thls is a case of political take some concrete steps to supply them vendena. Shri J)e.vendra Prasad Yadav's water and make a statement in the younger brother was killed deliberately. It is House ..•..• ( Int8fl1Jptions). because Shri Lalu Prasad Yadav was about to inaugurate the Phulparas Sub-division. SHRI KALKA' tiAs (KaroIbagh): Mr. Those people did not want it and resented It. Speaker, SIr, we have drawn the attention of They thought that because of initiative being the House towards this many times. This Is taken by Janata Dal Phulparas has been the factual position that Delhi is going to face made a sub division and later this credit will acute water crisis, as stated by the hon. go to them only. That is why quite deliber- Member. This has created a lot of tension In ately a conspiracy was hatched and hon. the minds of people. W. have been drawing Member, Shri Devendra Prasad Yadav's the attention of the administration for many youngerbrotherwas killed.