Delegitimizing Al-Qaida: Defeating an 'Army Whose Men Love Death'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Toulouse Murders

\\jciprod01\productn\J\JSA\4-1\JSA127.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-JUN-12 15:42 The Toulouse Murders Manfred Gerstenfeld* On March 19, 2012, Mohammed Merah, a Frenchman of Algerian ori- gin, killed a teacher and three children in front of the Toulouse Jewish school Otzar Hatorah. Earlier that month, he murdered three French soldiers. A few days after the Toulouse murders, Merah was killed in a shootout with French police.1 Murders in France and elsewhere are frequent, and a significant per- centage of murder victims are children. Yet the murder by this fanatic drew worldwide attention,2 which usually focused far more on the killing of the Jewish victims than that of the soldiers. For French Jews, this tragedy recalled events of past decades, the more so as the murderer was an Al Qaeda sympathizer. Six people in the Jewish Goldenberg restaurant in Paris were killed in 1982 by terrorists, most prob- ably from the Arab Abu Nidal group.3 In the past decade, antisemitic motives were behind murders of Jews committed by Muslims living in France. Sebastien Selam, a Jewish disc jockey, was killed by his Muslim childhood friend and neighbor Adel Amastaibou in 2003. Medical experts found the murderer mentally insane. When the judges accepted this conclusion, such finding prevented a trial in which the antisemitism of substantial parts of the French Muslim commu- 1. Murray Wardrop, Chris Irvine, Raf Sanchez, and Amy Willis, “Toulouse Siege as It Happened,” Telegraph, March 22, 2012. 2. Edward Cody, “Mohammed Merah, Face of the New Terrorism,” Washing- ton Post, March 22, 2012. -

The Struggle Against Musaylima and the Conquest of Yamama

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST MUSAYLIMA AND THE CONQUEST OF YAMAMA M. J. Kister The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The study of the life of Musaylima, the "false prophet," his relations with the Prophet Muhammad and his efforts to gain Muhammad's ap- proval for his prophetic mission are dealt with extensively in the Islamic sources. We find numerous reports about Musaylima in the Qur'anic commentaries, in the literature of hadith, in the books of adab and in the historiography of Islam. In these sources we find not only material about Musaylima's life and activities; we are also able to gain insight into the the Prophet's attitude toward Musaylima and into his tactics in the struggle against him. Furthermore, we can glean from this mate- rial information about Muhammad's efforts to spread Islam in territories adjacent to Medina and to establish Muslim communities in the eastern regions of the Arabian peninsula. It was the Prophet's policy to allow people from the various regions of the peninsula to enter Medina. Thus, the people of Yamama who were exposed to the speeches of Musaylima, could also become acquainted with the teachings of Muhammad and were given the opportunity to study the Qur'an. The missionary efforts of the Prophet and of his com- panions were often crowned with success: many inhabitants of Yamama embraced Islam, returned to their homeland and engaged in spreading Is- lam. Furthermore, the Prophet thoughtfully sent emissaries to the small Muslim communities in Yamama in order to teach the new believers the principles of Islam, to strengthen their ties with Medina and to collect the zakat. -

Growing up Bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World Growing up Bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World

[PDF-cvr]Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside ... Omar bin Laden - Wikipedia Osama bin Laden - Wikipedia Mon, 24 Sep 2018 07:55:00 GMT Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside ... Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World [Omar bin Laden, Najwa bin Laden, Jean Sasson] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. The New York Times calls GROWING UP BIN LADEN: The most complete account available of the terrorist’s immediate family. (May 15 Omar bin Laden - Wikipedia Omar bin Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (Arabic: ??? ?? ????? ?? ???? ?? ??? ?? ???? ?, ?Umar bin ?Us?mah bin Mu?ammad bin ?Awa? bin L?din; born 1981), better known as Omar bin Laden, is one of the sons of Osama bin Laden and his first wife and first cousin Najwa Ghanem (see Bin Laden family).He is the fourth-eldest son among 20 children of Osama ... (Download free ebook) Growing Up bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World Osama bin Laden - Wikipedia Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden was born in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, a son of Yemeni Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden, a millionaire construction magnate with close ties to the Saudi royal family, and Mohammed bin Laden's tenth wife, Syrian Hamida al-Attas (then called Alia Ghanem). -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Usama Bin Ladin's

Usama bin Ladin’s “Father Sheikh”: Yunus Khalis and the Return of al-Qa`ida’s Leadership to Afghanistan Harmony Program Kevin Bell USAMA BIN LADIN’S “FATHER SHEIKH:” YUNUS KHALIS AND THE RETURN OF AL‐QA`IDA’S LEADERSHIP TO AFGHANISTAN THE COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT www.ctc.usma.edu 14 May 2013 The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government. Author’s Acknowledgments This report would not have been possible without the generosity and assistance of the director of the Harmony Research Program at the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC), Don Rassler. Mr. Rassler provided me with the support and encouragement to pursue this project, and his enthusiasm for the material always helped to lighten my load. I should state here that the first tentative steps on this line of inquiry were made during my time as a student at the Program in Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. If not for professor Şükrü Hanioğlu’s open‐minded approach to directing my MA thesis, it is unlikely that I would have embarked on this investigation of Yunus Khalis. Professor Michael Reynolds also deserves great credit for his patience with this project as a member of my thesis committee. I must also extend my utmost appreciation to my reviewers—Carr Center Fellow Michael Semple, professor David Edwards and Vahid Brown—whose insightful comments, I believe, have led to a substantially improved and more thoughtful product. -

Ouse Foreign Affairs Subcommittee On

Testimony of Andrew Srulevitch, European Affairs Director Anti-Defamation League House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Hearing on Anti-Semitism: A Growing Threat to All Faiths February 27, 2013 Washington, DC 1 Testimony of Andrew Srulevitch Director of European Affairs Anti-Defamation League House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations February 27, 2013 Washington, DC Let me offer special thanks on behalf of the Anti-Defamation League and its National Director, Abraham Foxman, to Chairman Smith and all the Members of the Subcommittee for holding this hearing today and for the many hearings, letters, and rallying cries that have kept this issue front and center. Your commitment to the fight against anti-Semitism and your determination to move from concern to action inspires and energizes all of us. The history of the Jewish people is fraught with examples of the worst violations of human rights - forced conversions, expulsions, inquisitions, pogroms, and genocide. The struggle against the persecution of Jews was a touchstone for the creation of some of the foundational human rights instruments and treaties as well as the development of important regional human rights mechanisms like the human dimension commitments of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). We focus today on anti-Semitism but we are mindful that, in advancing the fight against anti-Semitism, we elevate the duty of governments to comply with broader human rights commitments and norms. That is the core of ADL’s mission: to secure justice and fair treatment for Jews in tandem with safeguarding the rights of all groups. -

Anti-Semitism: a Pillar of Islamic Extremist Ideology

Anti-Semitism: A Pillar of Islamic Extremist Ideology In a video message in August 2015, Osama bin Laden’s son, Hamza bin Laden, utilized a range of anti-Semitic and anti-Israel narratives in his effort to rally Al Qaeda supporters and incite violence against Americans and Jews. Bin Laden described Jews and Israel as having a disproportionate role in world events and the oppression of Muslims. He compared the “Zio- Crusader alliance led by America” to a bird: “Its head is America, one wing is NATO and the other is the State of the Jews in occupied Palestine, and the legs are the tyrant rulers that sit on the chests of the peoples of the Muslim Ummah [global community].” An undated image of al-Qaeda terrorist Osama bin Laden and his son, Hamza Bin Laden then called for attacks worldwide and demanded that Muslims “support their brothers in Palestine by fighting the Jews and the Americans... not in America and occupied Palestine and Afghanistan alone, but all over the world…. take it to all the American, Jewish, and Western interests in the world.” Such violent expressions of anti-Semitism have been at the core of Al Qaeda’s ideology for decades. Even the 9/11 terrorist attacks were motivated, in part, by anti-Semitism. Mohamed Atta, a key member of the Al Qaeda Hamburg cell responsible for the attacks, reportedly considered New York City to be the center of a global Jewish conspiracy, and Khalid Sheik Mohammed, who masterminded the attack, had allegedly previously developed several plans to attack Israeli and Jewish targets. -

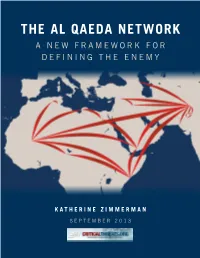

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL ........................................................................................................................ 2 DETAIL .......................................................................................................................... 10 AYMAN AL-ZAWAHIRI IS APPOINTED AS AL-QAEDA 'S LEADER ......................................................... 10 Responses to Al-Zawahiri's Appointment as Al-Qaeda's Leader ...................................................12 EULOGIES AND CALLS FOR VENGEANCE ....................................................................................... 15 Official Statements by Al-Qaeda's Branches: Central Motifs and Prominent Messages .............. 15 Announcements Made by the Jihadist Forums and the Media Institutes of Global Jihad Organizations ................................................................................................................................ 26 Reference Made by Prominent Writers ........................................................................................ 31 1 Osama Bin Laden's Elimination through the Prism of Al-Qaeda's Affiliates and Global Jihad Supporters – Follow-Up Report General On May 1 st 2001, an American commando force eliminated Al-Qaeda's leader, Osama bin Laden, in Abbottabad, Pakistan. A few days later, after an official announcement on behalf of the organization's general leadership, Al-Qaeda affiliates worldwide published official announcements containing eulogies over his death and praises for his path, -

Does Al-Qaeda Matter for Africa? How Affiliation with Al-Qaeda Influences the Behavior of African Sunni Extremist Groups

DOES AL-QAEDA MATTER FOR AFRICA? HOW AFFILIATION WITH AL-QAEDA INFLUENCES THE BEHAVIOR OF AFRICAN SUNNI EXTREMIST GROUPS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Hailey A. Hoffman, B.A. Washington, DC April 12, 2010 Copyright 2010 by Hailey A. Hoffman All Rights Reserved ii DOES AL-QAEDA MATTER FOR AFRICA? HOW AFFILIATION WITH AL-QAEDA INFLUENCES THE BEHAVIOR OF AFRICAN SUNNI EXTREMIST GROUPS Hailey A. Hoffman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Justine A. Rosenthal, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This paper seeks to investigate the frequently alleged trend that al-Qaeda is growing and becoming more dangerous in Africa. The study uses data from 2004 to 2009 provided by the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) on attacks and targeting by African jihadist groups to compare the behavioral trends of those that have joined al- Qaeda and those that have not. The data are interpreted to assess to what extent joining al-Qaeda seems to bring about behavioral changes in African Sunni terrorist organizations. The study finds that membership in the al-Qaeda organization correlates to drastic increases in activity levels and harm caused to victims in Africa. It also finds that groups that join al-Qaeda tend to increase their targeting of Western symbols and assets, although only moderately. From the insights gained through this analysis, the paper offers policy recommendations for the U.S. government. iii This thesis is dedicated to the brilliant students of the Georgetown University Security Studies Program (SSP) Class of 2010 for their counsel and support throughout the course of this project. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Case: 11-3490 Document: 145 Page: 1 04/16/2013 908530 32 11-3294-cv(L), et al. In re Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001 (Asat Trust Reg., et al.) UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2012 (Argued On: December 4, 2012 Decided: April 16, 2013) Docket Nos. 11-3294-cv(L), 11-3407-cv, 11-3490-cv, 11-3494-cv, 11-3495-cv, 11-3496-cv, 11-3500-cv, 11-3501- cv, 11-3502-cv, 11-3503-cv, 11-3505-cv, 11-3506-cv, 11-3507-cv, 11-3508-cv, 11-3509-cv, 11-3510- cv, 11-3511-cv, 12-949-cv, 12-1457-cv, 12-1458-cv, 12-1459-cv. _______________________________________________________________ IN RE TERRORIST ATTACKS ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 (ASAT TRUST REG., et al.) JOHN PATRICK O’NEILL, JR., et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. ASAT TRUST REG., AL SHAMAL ISLAMIC BANK, also known as SHAMEL BANK also known as BANK EL SHAMAR, SCHREIBER & ZINDEL, FRANK ZINDEL, ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, SR., ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, JR., MARTIN WATCHER, ERWIN WATCHER, SERCOR TREUHAND ANSTALT, YASSIN ABDULLAH AL KADI, KHALED BIN MAHFOUZ, NATIONAL COMMERCIAL BANK, FAISAL ISLAMIC BANK, SULAIMAN AL-ALI, AQEEL AL-AQEEL, SOLIMAN H.S. AL-BUTHE, ABDULLAH BIN LADEN, ABDULRAHMAN BIN MAHFOUZ, SULAIMAN BIN ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, SALEH ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH SALAIMAN AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH OMAR NASEEF, TADAMON ISLAMIC BANK, ABDULLAH MUHSEN AL TURKI, ADNAN BASHA, MOHAMAD JAMAL KHALIFA, BAKR M. BIN LADEN, TAREK M. BIN LADEN, OMAR M. BIN LADEN, DALLAH AVCO TRANS ARABIA CO. LTD., DMI ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES S.A., ABDULLAH BIN SALEH AL OBAID, ABDUL RAHMAN AL SWAILEM, SALEH AL-HUSSAYEN, YESLAM M. -

What the Religions Named in the Qur'ān Can Tell Us

WHAT THE RELIGIONS NAMED IN THE QUR’ĀN CAN TELL US ABOUT THE EARLIEST UNDERSTANDING OF “ISLAM” A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By Micah David Collins B.A., Wright State University, 2009 2012 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES June 20, 2012 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Micah David Collins ENTITLED What the Religions Named In The Qur’an Can Tell Us About The Earliest Understanding of “Islam” BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Masters of Humanities. _______________________ Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Project Director _______________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Director, Masters of Humanities Program College of Liberal Arts Committee on Final Examination: _______________________ Awad Halabi, Ph.D. _______________________ David Barr, Ph.D. _______________________ Mark Verman, Ph.D. _______________________ Andrew T. Hsu, Ph.D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Collins, Micah. M.A. Humanities Department, Masters of Humanities Program, Wright State University, 2012. What The Religions Named In The Qur’ān Can Tell Us About The Earliest Understanding of “Islam”. Both Western studies of Islam as well as Muslim beliefs assert that the Islamic holy text, the Qur’ān, endeavored to inaugurate a new religion, separate and distinct from the Jewish and Christian religions. This study, however, demonstrates that the Qur’ān affirms a continuity of beliefs with the earlier revealed texts that suggest that the revelations collected in the Qur’ān did not intend to define a distinct and separate religion. By studying the various historical groups named in the Qur’ān – such as the Yahūd, Ṣabī’ūn, and Naṣārā – we argue that the use of the term “islam” in the Qur’ān relates more to the general action of “submission” to the monotheistic beliefs engaged in by existing Jewish and Nazarene communities within Arabia.