An Evaluation of the Forest of Dean Integrated Rural Development (FODIRD) Programme - 2000-2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environment Agency Midlands Region Wetland Sites Of

LA - M icllanAs <? X En v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y ENVIRONMENT AGENCY MIDLANDS REGION WETLAND SITES OF SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC INTEREST REGIONAL MONITORING STRATEGY John Davys Groundwater Resources Olton Court July 1999 E n v i r o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................... 3 1.) The Agency's Role in Wetland Conservation and Management....................................................3 1.2 Wetland SSSIs in the Midlands Region............................................................................................ 4 1.3 The Threat to Wetlands....................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Monitoring & Management of Wetlands...........................................................................................4 1.5 Scope of the Report..............................................................................................................................4 1.6 Structure of the Report.......................................................................................................................5 2 SELECTION OF SITES....................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Definition of a Wetland Site................................................................................................................7 -

AYLBURTON COMMUNITY PLAN June 2009

AYLBURTON COMMUNITY PLAN June 2009 © Aylburton Parish Council 2009 PROPRIETARY INFORMATION This document contains proprietary information belonging to Aylburton Parish Council and may neither be wholly or partially reproduced nor disclosed without the prior written permission of Aylburton Parish Council. Issue 1 Aylburton Community Plan Page 2 of 50 REVISION HISTORY Issue Date Status Comment For ACPSC & Parish Council A Feb 2009 Revised Comment For presentation at Public B 3rd April 2009 Minor Revisions Meeting 3rd April 2009 1 June 2009 Formal Issue Minor Revisions REVIEW (For the last issue shown on Revision History) Signature Print Name Position Date M.G.Bloomfield ACPSC Secretary S.C.Rutherford ACPSC Chair M.J.Prakel PC Chair AMENDMENTS To assist in identifying the amendments in each revised FORMAL issue of this document, a vertical line is displayed in the right hand margin opposite new or revised text. Vertical lines marking previous amendments are deleted at each revised issue of the document. Issue 1 Aylburton Community Plan Page 3 of 50 ABBREVIATIONS LIST ACPSC Aylburton Community & Parish Plan Steering Group ACRE Action with Communities in Rural England ALARP As Low As Reasonably Practicable DECC HM Government Department of Energy and Climate Change. FoDDC Forest of Dean District Council GCC Gloucestershire County Council GRCC Gloucestershire Rural Community Council LSP Local Strategic Partnership MAIDeN Multi-Agency Database for Neighbourhoods MHMC Memorial Hall Management Committee MoD Ministry of Defence PC Parish council PCSO Police Community Support Officers SCOSLA Standing Conference on Severnside Local Authorities SSG (Nuclear Power) Station Stakeholder Group SWERDA SW of England Regional Development Agency Issue 1 Aylburton Community Plan Page 4 of 50 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents the Aylburton Community Plan, as developed after extensive formal consultation with the residents of Aylburton in Gloucestershire. -

JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 11 The Western Approaches: Falmouth Bay to Kenfig edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1996 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group and supported by WWF-UK. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, J.C. Brooksbank, A.L. Buck Administration & editorial assistance C.A. Smith, R. Keddie, J. Plaza, S. Palasiuk, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice came from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group Prof. S.J. Lockwood MAFF Directorate of Fisheries Research C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. -

THE FOREST of DEAN GLOUCESTERSHIRE Archaeological Survey Stage 1: Desk-Based Data Collection Project Number 2727

THE FOREST OF DEAN GLOUCESTERSHIRE Archaeological Survey Stage 1: Desk-based data collection Project Number 2727 Volume 2 Appendices Jon Hoyle Gloucestershire County Council Environment Department Archaeology Service November 2008 © Archaeology Service, Gloucestershire County Council, November 2008 1 Contents Appendix A Amalgamated solid geology types 11 Appendix B Forest Enterprise historic environment management categories 13 B.i Management Categories 13 B.ii Types of monument to be assigned to each category 16 B.iii Areas where more than one management category can apply 17 Appendix C Sources systematically consulted 19 C.i Journals and periodicals and gazetteers 19 C.ii Books, documents and articles 20 C.iii Map sources 22 C.iv Sources not consulted, or not systematically searched 25 Appendix D Specifications for data collection from selected source works 29 D.i 19th Century Parish maps: 29 D.ii SMR checking by Parish 29 D.iii New data gathering by Parish 29 D.iv Types of data to be taken from Parish maps 29 D.v 1608 map of the western part of the Forest of Dean: Source Works 1 & 2919 35 D.vi Other early maps sources 35 D.vii The Victoria History of the County of Gloucester: Source Works 3710 and 894 36 D.viii Listed buildings information: 40 D.ix NMR Long Listings: Source ;Work 4249 41 D.x Coleford – The History of a West Gloucestershire Town, Hart C, 1983, Source Work 824 41 D.xi Riverine Dean, Putley J, 1999: Source Work 5944 42 D.xii Other text-based sources 42 Appendix E Specifications for checking or adding certain types of -

Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club

TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLII 1978 PART III TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME XLII 1978 PART III - TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1976, 1977, 1978 Page Proceedings 1976 1 1977 115 1978 211 An Introduction to the Houses of Pembrokeshire, by R. C. Perry 6 The Origins of the Diocese of Hereford, by J. G. Hillaby 16 © Woolhope Naturalists Field Club 1978 The Palaces of the Bishop of Hereford, by J. W. Tonkin 53 All contributions to The Woolhope Transactions are COPYRIGHT. None of them may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording Victorian Church Architecture in the Diocese of Hereford, or otherwise without the prior permission of the writers. Applications to by 1-1. J. Powell - 65 reproduce contributions, in whole or in part, should be addressed, in the first instance, to the editor whose address is given in the LIST OF OFFICERS. Leominster Fair, 1556, by J. Bathurst and E. J. L. Cole - 72 Crisis and Response: Reactions in Herefordshire to the High Wheat Prices of 1795-6, by W. K. Parker - 89 Medieval Life and thought, by W. B. Haynes 120 Pembridge and mature Decorated architecture in Herefordshire, by R. K. Morris - 129 The Preferment of Two Confessors to the See of Hereford: Robert Mascall and John Stanbury, by Ann Rhydderch 154 Mortality in the Diocese of Hereford, 1442-1541, by M. A. Faraday 163 The Architectural History of Goodrich Court, Herefordshire, by Hugh Meller - 175 T. -

Proposed Mitigation

Homes and Communities Agency Environmental Statement Addendum Vol. 2 - Hybrid Planning Application – Northern Quarter, Cinderford Proposed Mitigation Phase 1 Construction Designated Sites 7.260 None of the statutorily designated sites identified within the desktop study search area will be directly affected by the phase 1 construction works. 7.261 Those sites designated for their bat populations in the three tables above may however be indirectly affected by the proposed phase 1 construction works through potential impacts on the bats, when outside the boundary of the designated site and within the Hybrid Application Site. As such the mitigation measures detailed within the bats section below will apply. See paragraphs 7.259a – 7.259k and the phase 1 Impact table for discussion of impacts on the Severn Estuary SAC, SPA and Ramsar, Walmore Common SPA and Ramsar site and on the Speech House Oaks SSSI. 7.262 As for the policy based designated sites, both the direct (as detailed under the individual habitat features in the tables above, where possible) and indirect impacts identified on the Cinderford Linear Park Key Wildlife Site will be addressed through the mitigation measures for the individual ecological features detailed below. Habitats 7.263 It is not possible to mitigate the loss of all habitats arising from the college / section 1 spine road construction and from creation of a mitigation area on an area for area basis, either within the footprint of the development at the Hybrid Application Site or within the wider area. Potential fragmentation of habitats along Old Engine Brook and along the eastern boundary of the Hamblett Land (as labelled on Figure 7.5) can be mitigated in the short term through the inclusion of brash corridors (as detailed in paragraph 7.298 below). -

Parish Register Guide L

Lancaut (or Lancault) ...........................................................................................................................................................................3 Lasborough (St Mary) ...........................................................................................................................................................................5 Lassington (St Oswald) ........................................................................................................................................................................7 Lea (St John the Baptist) ......................................................................................................................................................................9 Lechlade (St Lawrence) ..................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Leckhampton, St Peter ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Leckhampton (St Philip and St James) .............................................................................................................................................. 15 Leigh (St Catherine) ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Leighterton ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Lydbrook, Joy's Green, and Ruardean Walk 8 6½ Miles

Walking Through Dean History Walk Eight Walk 8 6½ miles (10½ km) Lydbrook, Joy’s Green, and Ruardean GO PAST THE BARRIER and follow the soon be seen in the valley below. Continue dirt track down the valley to the right of the on the level track, ignoring a fork downhill to stream (i.e., do not cross road). Keep left at a the left, but soon bear right uphill by a fence Railway and colliery remains, a Tudor house, and lovely views of Wales and fork, still following the stream (Greathough (with a former chapel up to the right) onto Herefordshire. The walk is mainly on woodland tracks and an old railway trackbed Brook). An outcrop of Pennant Sandstone a grass track between houses (part of the (now a cycle track), with some field paths and lanes; one steady climb; 8 stiles. (part of the Coal Measures) is seen on the former Severn and Wye’s tramroad which right, after about 250 yds. Just after this, preceded the railway). This comes out at START at ‘Piano Corner’ on minor road (Pludds Road) between Brierley and opposite a small open area, is a small cutting the end of a tarmac lane. To the right, a dirt The Pludds (about 500 yds from junction with A4136 Monmouth–Mitcheldean with a pipe protruding from the blocked- track follows the route of the Bishopswood road): GR SO 621154. Park on gravel area by metal barrier on left-hand up adit of Favourite Free Mine (1). Note the Tramroad (10), and there was an incline down side of road when travelling away from Brierley and the A4136. -

Compiled by SUSAN VAUGHAN

Index Compiled by SUSAN VAUGHAN Illustrations are denoted by page numbers in italics or by illus where figures are scattered throughout the text. The letter n following a page number indicates that the reference will be found in a note. The contents of book reviews have not been indexed. Places within historic Gloucestershire are arranged by modern civil parish. Other places are followed by their present county or administrative area. The following abbreviations have been used in this index: d. – died; ed. – editor; fl. – floruit;illus. – illustrated; m. – married; N. Som – North Somerset; S. Glos. – South Gloucestershire; Som. – Somerset; Wilts. – Wiltshire. abbeys/religious houses Ampney Crucis, Abbey Home Farm, survey 270 Bruton 214 Andoversford Gloucester, see Llanthony Secunda priory; St Owdeswell Manor, land at, survey and Peter’s Abbey under Gloucester evaluation 270 Tewkesbury 299–300 Templefields, land to rear of, evaluation 270 Westbury-on-Trym 251–2 animal bone Winchcombe 302 Neolithic, Winchcombe 178 Abbotsbury (Dorset) 221, 223, 224, 227 Bronze Age, Winchcombe 178 Ablington (Wilts.), manor 219 Iron Age, Churchdown 64, 66 Acton family 264 Iron Age–Romano-British John de I 261 Bourton-on-the-Water 104 John de II 261 Winchcombe 147–8, 149, 152 John de III 261, 262, 263 Romano-British John de IV 262, 263 Churchdown 64, 65–6, 65 Milicent 262 Winchcombe 178 Odo 261, 262, 263 Anne of Denmark, Queen 228 Sir Richard de 208 armlet, shale, Iron Age/Romano-British 83, 103 Adam, John ap 210 Arnold, Graham Adams, Amanda, see Crowther, Steve, & Adams, Archaeological Review 293 Amanda & Nicholson, Michael, Archaeological Review Aird, Sir John and Company 237 300 Alderton, land at Lower Stanley Farm, Arnold family 14 evaluation 269–70 Ashchurch Alkington A46, land off, evaluation 270 manor 208 Fiddington manor 261 Wick 211 Ashleworth, manor 23 Aller Aston, Sir Robert de 208 Elizabeth, m. -

Allocations Plan Submission Draft Incorporating Main Modifications

Forest of Dean District Council Allocations Plan Submission Draft incorporating Main Modifications October 2017 Forest of Dean District Council | Allocations Plan Submission Draft incorporating Main Modifications October 2017 INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL POLICIES 1 Preface 8 2 Introduction 9 3 District Wide Policies 21 4 Policy Overview and area policies not related to settlements 38 POLICIES FOR TOWNS AND OTHER SETTLEMENTS 5 Cinderford and Ruspidge 76 6 Lydney 94 7 Coleford 124 8 Newent 146 9 Alvington 166 10 Aylburton 170 11 Beachley 174 12 Blakeney 176 13 Bream 180 14 Brierley 186 15 Brockweir 188 16 Bromsberrow Heath 190 17 Clearwell 192 18 Drybrook and Harrow Hill 196 19 Dymock 202 20 Edge End 206 21 Ellwood 208 22 English Bicknor 212 Forest of Dean District Council | Allocations Plan Submission Draft incorporating Main Modifications October 2017 23 Hartpury 216 24 Huntley 220 25 Kempley Green 224 26 Littledean 226 27 Longhope 230 28 Lydbrook, Joys Green and Worral Hill 236 29 Mitcheldean 244 30 Newland 250 31 Newnham on Severn 252 32 Northwood Green 258 33 Oldcroft and Viney Hill 260 34 Parkend 264 35 Redbrook 268 36 Redmarley 272 37 Ruardean 276 38 Ruardean Hill 280 39 Ruardean Woodside 284 40 Sedbury and Tutshill 286 41 Sling 294 42 St. Briavels 298 43 Staunton (Coleford) 300 44 Staunton and Corse 302 45 Tibberton 310 Forest of Dean District Council | Allocations Plan Submission Draft incorporating Main Modifications October 2017 Tutshill (see Sedbury) 46 Upleadon 312 47 Upper Soudley 314 48 Westbury on Severn 318 49 Whitecroft Pillowell -

Mondays to Fridays

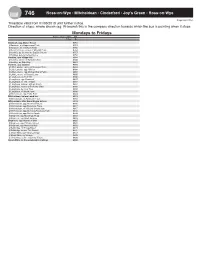

746 Ross-on-Wye - Mitcheldean - Cinderford - Joy’s Green - Ross-on-Wye Stagecoach West Timetable valid from 01/09/2019 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Col Notes G Boxbush, opp Manor House 0751 § Boxbush, o/s Hopeswood Park 0751 § Boxbush, nr The Rock Farm 0752 § Dursley Cross, corner of May Hill Turn 0754 § Huntley, by St John the Baptist Church 0757 § Huntley, before Newent Lane 0758 Huntley, opp Village Hall 0800 § Huntley, corner of Byfords Close 0800 § Huntley, on Oak Way 0801 Huntley, opp Sawmill 0802 § Little London, corner of Blaisdon Turn 0803 § Little London, opp Hillview 0804 § Little London, opp Orchard Bank Farm 0804 § Little London, nr Chapel Lane 0805 § Longhope, on Zion Hill 0806 § Longhope, opp Memorial 0807 § Longhope, nr The Temple 0807 § Longhope, before Latchen Room 0807 § Longhope, corner of Bathams Close 0808 § Longhope, by Yew Tree 0808 § Longhope, nr Brook Farm 0808 § Mitcheldean, opp Harts Barn 0809 Mitcheldean, before Lamb Inn 0812 § Mitcheldean, nr Abenhall House 0812 Mitcheldean, after Dene Magna School 0815 § Mitcheldean, opp Abenhall House 0816 § Mitcheldean, opp Dunstone Place 0817 § Mitcheldean, nr Mill End School stop 0817 § Mitcheldean, opp Stenders Business Park 0818 § Mitcheldean, opp Dishes Brook 0820 § Drybrook, opp Mannings Road 0823 § Drybrook, opp West Avenue 0823 Drybrook, opp Hearts of Oak 0825 § Drybrook, opp Primary School 0825 § Drybrook, opp Memorial Hall 0826 § Nailbridge, nr Bridge Road 0829 § Nailbridge, before The Branch 0832 § Steam Mills, by Primary School 0833 § Steam Mills, by Garage 0835 § Cinderford, before Industrial Estate 0836 Steam Mills, nr Gloucestershire College 0840 746 Ross-on-Wye - Mitcheldean - Cinderford - Joy’s Green - Ross-on-Wye Stagecoach West For times of the next departures from a particular stop you can use traveline-txt - by sending the SMS code to 84268. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2012

HERITAGE AT RISK 2012 / SOUTH WEST Contents HERITAGE AT RISK 3 Reducing the risks 7 Publications and guidance 10 THE REGISTER 12 Content and assessment criteria 12 Key to the entries 15 Heritage at risk entries by local planning authority 17 Bath and North East Somerset (UA) 19 Bournemouth (UA) 22 Bristol, City of (UA) 22 Cornwall (UA) 25 Devon 62 Dorset 131 Gloucestershire 173 Isles of Scilly (UA) 188 North Somerset (UA) 192 Plymouth, City of (UA) 193 Poole (UA) 197 Somerset 197 South Gloucestershire (UA) 213 Swindon (UA) 215 Torbay (UA) 218 Wiltshire (UA) 219 Despite the challenges of recession, the number of sites on the Heritage at Risk Register continues to fall. Excluding listed places of worship, for which the survey is still incomplete,1,150 assets have been removed for positive reasons since the Register was launched in 2008.The sites that remain at risk tend to be the more intractable ones where solutions are taking longer to implement. While the overall number of buildings at risk has fallen, the average conservation deficit for each property has increased from £260k (1999) to £370k (2012).We are also seeing a steady increase in the proportion of buildings that are capable of beneficial re-use – those that have become redundant not because of any fundamental lack of potential, but simply as the temporary victims of the current economic climate. The South West headlines for 2012 reveal a mixed picture. We will continue to fund Monument Management It is good news that 8 buildings at risk have been removed Schemes which, with match-funding from local authorities, from the Register; less good that another 15 have had to offer a cost-effective, locally led approach to tackling be added.