Arab TV-Audiences: Negotiating Religion and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22 Vertiefungstext 13.Mdi

TBS 16 The Appeal of Sami Yusuf and the Search for Islamic Authenticity by Christi... Page 1 of 13 PEER REVIEWED ARTICLE: The Appeal of Sami Yusuf and the Search for Islamic Authenticity By Christian Pond A quick glance at the top 40 most requested songs on the Web site for the popular Arabic music video channel Melody Hits TV reveals the latest and greatest from stars such as Lebanon’s Nancy Ajram—infamous for her sexually suggestive videos—as well as others like America’s rapper Eminem and Egypt’s crooner Tamer Hosny. Next to each song’s title and number is also displayed a picture of the artist. At number 32, next to her hit Megamix, is a picture of Britney Spears staring at the viewer with the fingers of her right hand resting suggestively on her bottom lip. At number 35, popular rapper 50 Cent is shown in front of an expensive sports car wearing a fur coat, diamond-studded chain and black bandana. Wedged between the two at number 34 is the British Muslim singing phenomenon Sami Yusuf with his latest hit Hasbi Rabbi.(1) Well-dressed, sporting a fashionably cut, close-cropped beard and preferring tailored black suits to traditional dress, he is famous for his glitzy religious CDs and music videos. Born in 1980 to Azerbaijani parents, Sami Yusuf grew up in London and first studied music under his father, a composer. From a young age he learned to play various instruments and at the age of 18 was granted a scholarship to study at the Royal Academy of Music in London.(2) In 2003, Yusuf released his first album entitled Al Mu’allim (The Teacher). -

TVEE LINKER Arabic Channels

lebanon united Arabic Egypt Dubai Tele Liban Rotana Classic Misr 25 Modem Sport MTV Lebanon Rotana masriya ON TV Abu dhabi LBC Rotana_aflam Alkaherawalnas 2 Al Watan OTV Rotana_cinema Blue Nile Sama Dubai nbn Rotana_music Nile Dubai MTV TV panorama_action Nile Sport Dubai HD Al jadeed panorama_comedy Nile Cinema Dubai Sports Al jadeed live fx_arabia Nile Comedy Noor Dubai Future TV infinity Nile News Dubai one Al mayadeen Iraq Nile Family Dubai Sport 1 Al Manar Dream_1 Nile Life National Geographic Abudhabi Asia News Lebanon Al sharqiya Drama CBC tv Scope TV Charity TV Al sharqiya Music Cairo Cinema Abu Dhabi Sports 1 Noursat Al Shabab Al sharqiya News Cima Sharjah Nour sat Lebanon Al Sharqiya CBC +2 abu dhabi drama Syria Al sharqia drama CBC Drama Mbc Action ANN Sharqia CBC Egypt Mbc Syria Drama Beladi Citurss TV Mbc 2 Syria Al Babeleyia Masrawi Aflam Rotana Khalijia Orient TV 2 Al Fayhaa Al Qahira Al Youm Live Rotana Cinema Al Tarbaweiyah Al Soriyah Ishtar Moga Comedy Rotana Music Nour El Sham AI Iraqiya Cnbc Arabia Dubai Sport 3 Halab TV Al Sumaria Aljayat Series Saudi Arabic Qatar Al kout Miracle TV Al Thakafiyah Aljazeera Al Forat SAT7 Kids Al Ekhbariya TV Live Aljazeera Sports+1 Al hurra_iraq Sat7 Arabic TV Egypt Al Ekhbariya Aljazeera Sports+3 Sharqia News TRT Arabic Al Eqtisadiyah Aljazeera Sports+9 Al Rasheed TV Al Karma KTV3 plus Aljazeera Sports+8 Hanibal Al Malakot Al Sabah Aljazeera Sports+10 Al Baghdadia Al Kawri Alkass KSA Riyadiah Aljazeera sports x Baghdad Al Ahly Club KSA 1 Aljazeera sports3 Iraq Afaq Alalamia KSA 2 -

Methods and Methodologies in Fiqh and Islamic Economics

Methods and Methodologies in Fiqh and Islamic Economics Dr. Muhammad Yusuf Saleem Department of Economics Kulliyyah of Economics and Management Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract. This paper intends to examine the methods of reasoning that are employed in Fiqh and critically discuss their adoption in Islamic economics. The paper argues that the methods used in Fiqh are mainly designed to find out whether or not a certain act is permissible or prohibited. Islamic economics, on the other hand, is a social science. Like any other social science its proper unit of analysis is the society itself. Methodologies of Fiqh and Islamic economics also differ as the former focuses on prescriptions. It prescribes what an individual should do or avoid. In contrast, Islamic economics is more concerned with describing economic phenomena. While Fiqh, especially worship (Ibadat) type, prescriptions are permanent in nature and for all individuals, economic descriptions may change from time to time and from society to another. This paper argues that the methods of reasoning for discovering the truth in fiqh and Islamic economics are not necessarily identical. While fiqh has a well developed methodology in the form of usul al-fiqh, Islamic economics in its search for finding the truth should rely on a methodology that suits its social and descriptive nature. Introduction This paper begins with a discussion on methods and methodologies. It explains how the adoption of different standards for the acceptability of certain evidence can lead to differences in approaches and methodologies. It also discusses that various disciplines have different units of analysis or objects of inquiries. -

Ar Risalah) Among the Moroccan Diaspora

. Volume 9, Issue 1 May 2012 Connecting Islam and film culture: The reception of The Message (Ar Risalah) among the Moroccan diaspora Kevin Smets University of Antwerp, Belgium. Summary This article reviews the complex relationship between religion and film-viewing among the Moroccan diaspora in Antwerp (Belgium), an ethnically and linguistically diverse group that is largely Muslim. A media ethnographic study of film culture, including in-depth interviews, a group interview and elaborate fieldwork, indicates that film preferences and consumption vary greatly along socio-demographic and linguistic lines. One particular religious film, however, holds a cult status, Ar Risalah (The Message), a 1976 historical epic produced by Mustapha Akkad that deals with the life of the Prophet Muhammad. The film’s local distribution is discussed, as well as its reception among the Moroccan diaspora. By identifying three positions towards Islam, different modes of reception were found, ranging from a distant and objective to a transparent and subjective mode. It was found that the film supports inter-generational religious instruction, in the context of families and mosques. Moreover, a specific inspirational message is drawn from the film by those who are in search of a well-defined space for Islam in their own lives. Key words: Film and diaspora, media ethnography, Moroccan diaspora, Islam, Ar Risalah, The Message, Mustapha Akkad, religion and media Introduction The media use of diasporic communities has received significant attention from a variety of scholarly fields, uncovering the complex roles that transnational media play in the construction of diasporic connectedness (both ‘internal’ among diasporic communities as well as with countries of origin, whether or not ‘imagined’), the negotiation of identity and the enunciation of socio-cultural belongings. -

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror meforum.org Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 From Birmingham to Cairo �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Origins ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Branches and Officials ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Government Support ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 17 Terror Finance ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20 Hate Speech ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Charity, Extremism & Terror ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 29 What Now? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 Executive Summary What is Islamic Relief? Islamic Relief is one of the largest Islamic charities in the world. Founded in 1984, Islamic Relief today maintains -

Televangelists, Media Du'ā, and 'Ulamā'

TELEVANGELISTS, MEDIA DU‘Ā, AND ‘ULAMĀ’: THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN MODERN ISLAM A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies By Tuve Buchmann Floden, M.A. Washington, DC August 23, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Tuve Buchmann Floden All Rights Reserved ii TELEVANGELISTS, MEDIA DU‘Ā, AND ‘ULAMĀ’: THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN MODERN ISLAM Tuve Buchmann Floden, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Felicitas M. Opwis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The rise of modern media has led to debates about religious authority in Islam, questioning whether it is fragmenting or proliferating, and exploring the state of the ‘ulamā’ and new groups like religious intellectuals and Muslim televangelists. This study explores these changes through a specific group of popular preachers, the media du‘ā, who are characterized by their educational degrees and their place outside the religious establishment, their informal language and style, and their extensive use of modern media tools. Three media du‘ā from the Arab world are the subject of this study: Amr Khaled, Ahmad al-Shugairi, and Tariq al- Suwaidan. Their written material – books, published interviews, social media, and websites – form the primary sources for this work, supplemented by examples from their television programs. To paint a complete picture, this dissertation examines not only the style of these preachers, but also their goals, their audience, the topics they address, and their influences and critics. This study first compares the media du‘ā to Christian televangelists, revealing that religious authority in Islam is both proliferating and differentiating, and that these preachers are subtly influencing society and politics. -

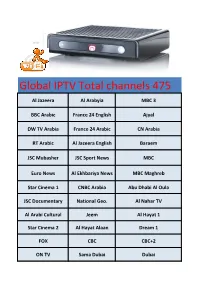

Global IPTV Total Channels 475

Global IPTV Total channels 475 Al Jazeera Al Arabyia MBC 3 BBC Arabic France 24 English Ajyal DW TV Arabia France 24 Arabic CN Arabia RT Arabic Al Jazeera English Baraem JSC Mubasher JSC Sport News MBC Euro News Al Ekhbariya News MBC Maghreb Star Cinema 1 CNBC Arabia Abu Dhabi Al Oula JSC Documentary National Geo. Al Nahar TV Al Arabi Cultural Jeem Al Hayat 1 Star Cinema 2 Al Hayat Alaan Dream 1 FOX CBC CBC+2 ON TV Sama Dubai Dubai Rotana Masrya ERI TV Eritrea MBC Drama CBC Drama Abu Dhabi Drama Oscar Drama Al Nahar Drama Al Hayat Muslsalt Rotana Khalijiah iFilm Al Hayat Cinema Rotana Cinema Al Ghad Al Arabi Cima Al Sharqiya Al Forat Al Sumaria Al Rasheed Al Baghdadia Al Iraqia Ishtar TV KNN ANB MBC Bollywood LBC Sat Future USA Liban TV OTV Lebanon NBN Future Hawakom MTV Lebanon Rotana Clip Hannibal Melody Wanasah Rotana Classic Fox Movies ME Al Hurria Arabica Music Saudi 1 ESC Payam Jordan Qatar Al Mayadeen TV Kuwait Sudan Mazzika Oman Al Sharjah Al Zahabiya Al Masrawia Nessma Al Khadhra Zee Aflam Al Rai Noor Al Sham Dubai One Orient Infinity MBC Max TRT Arapca Al Quds MBC Action Lybia Al Ahrar Al Anwar MBC 2 Canal Algerie Al Watan MBC 4 Algerie-3 Moga Comedy FX Iraqia Sport Al Saeedah Al Shorooq TV Karbala Sat. Ch. Al Maaref Iqraa Arabic Saudi 2 Noursat Noor Dubai Al Quran Al Kreem KurdSat Kurdistan TV Blue Nile Somali Channel Somalisat Somaliland Nat. TV Royal Somali Arriyadia - Morocco Abu Dhabi Sport Dubai Sport 1 Saudi Sport 1 Saudi Sport 2 HCTV Somali Al Jazeera Sport 1 Al Jazeera Sport 2 Jazeera Sport Glob. -

Powers, Duties and Liabilities of Company Directors: a Comparative Study of the Law and Practice in the UK and Saudi Arabia

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The Law School Powers, duties and liabilities of company directors: A comparative study of the law and practice in the UK and Saudi Arabia Abdullah Nasser Aldahmash (November 2020) A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Abstract Due to the globalisation of business and the concept of borderless business activities, these new phenomena need business management to be open and adopt and practice management’ skills with the international in mind, and give good consideration to the circumstances of the internationalisation of the business through directors having powers as provided under contract and law. The financial crises in previous years have demonstrated the importance of directors’ duties to manage the company's affairs properly; these crises were a result of many cases of fraud and mismanagement. The directors’ duties in the UK and the KSA have been codified to enhance the clarity of the law and make it easier for the responsibilities of directors towards the company and others to be understood. It also aims to prevent fraud and mismanagement that causes corporate collapse. This study investigates and analyses the powers, duties and liabilities of the directors in Saudi Arabia and the UK in order to demonstrate the extent to which these regulation work effectively. This is by a critical evaluation of relevant legislation and case law on the subject matter of the study and demonstrating practical problems, which may result from some legislation. By doing this, the study provides an accurate picture of the directors' powers, duties and liabilities, and provides solutions to practical problems of legislation in the same context. -

Arabised Terms in the Holy Quran Facts Or Fiction: History and Criticism

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 4, No. 3; 2014 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Arabised Terms in the Holy Quran Facts or Fiction: History and Criticism Basma Odeh Salman Al-Rawashdeh1 1 Al-Balqa Applied University, Princess Rahmah University College, Jordan Correspondence: Basma Odeh Salman Al-Rawashdeh, Al-Balqa Applied University, Princess Rahmah University College, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 13, 2014 Accepted: March 4, 2014 Online Published: August 29, 2014 doi:10.5539/ells.v4n3p90 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v4n3p90 Abstract Nowadays, to tackle a subject fifteen hundred years old is not an easy task. Especially people are looking for simple and interesting issues. However, when it comes to faith, even if its vocabulary hard to understood, its subject must be interesting and attractive one. Thus, current study discusses an important issue that is, the alleged presence of foreign words in the Quran, while Quran declares the opposite of that. This issue has kept philologists and scholars from so long until today discussing, debating and arguing its core elements. Some supported the Quran point of view; other opposed while assuring the presence of foreign words in the Quran, while the third group takes the middle road between the two extremes. Relying on numerous and trust worthy publications such as author Ibn Faris and other evidence, present author could prove that the Quran is entirely free from foreign terms. Keywords: Quran, Arabised, foreign terms, Ibn Faris, supporters, denying, intermediate group 1. -

FSU Senate Keeps New President Two Jewish Pioneers Are Building An

Health & Fitness Section B WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 44, NO. 43 JUNE 26, 2020 4 TAMUZ, 5780 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ FSU senate keeps new president By Jackson Richman (JNS) —The student senate at Florida State University voted on June 18 not to remove its new president, despite his past anti-Semitic posts. The final tally was not disclosed. Ahmad Daraldik was selected by the Florida State University Student Senate to replace its previous president, Jack Den- ton, who was accused of racism. Along those lines, Daraldik faced calls to step down after screenshots surfaced of past anti-Semitic posts. “Being in a position of power Ahmad Daraldik presented Ahmad the opportu- nity to represent all students has made other troubling at FSU, including Jewish and remarks. Israeli students. He could have While claiming to oppose taken the opportunity to learn, anti-Semitism, he equated open up a dialogue with us, Israelis with Nazis and Pal- and work with us to create a estinian experiences with the shared understanding,” the Holocaust on a website he cre- group Noles for Israel said ated devoted to this falsehood. Josh Hasten in a statement on June 12. A caption on the website reads, Ari Abramowitz (l) and Jeremy Gimpel in front of their house of worship on Arugot Farms. “Instead, he chose to further “The Holocaust never ended, marginalize our community it just moved to Palestine… ” and create further polarization In 2012, he shared on his on our campus.” now-deleted Facebook ac- Two Jewish pioneers are building an “As a university Senate count a post that glorified president, Ahmad should not the swastika. -

The Influence of Arabic Language Learning on Understanding of Islamic Legal Sciences—A Study in the Sultan Idris Education University

International Education Studies; Vol. 11, No. 2; 2018 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Influence of Arabic Language Learning on Understanding of Islamic Legal Sciences—A Study in the Sultan Idris Education University Nahla A. K. Alhirtani1 1 Faculty of Languages, Sultan Idris Education University, Malaysia Correspondence: Nahla A. K. Alhirtani, Faculty of Languages, Sultan Idris Education University, Malaysia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 15, 2017 Accepted: October 19, 2017 Online Published: January 26, 2018 doi:10.5539/ies.v11n2p55 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n2p55 Abstract The most important in Islamic Legal Sciences is Arabic Language, because of its necessity for Muslims to understand the Islamic Legal Provisions in Qur’an and Hadith which are in Arabic and informed by Arabs, thus, to understand these sciences it is a must to learn Arabic to discern the meanings and benefits of Islamic Texts and Provisions. So based on induction and analysis, this study aims to illustrate the function of Arabic Language as a tool serves the Islamic Legal Sciences in the Sultan Idris Education University, by a questionnaire was disseminated among the students of Arabic Language to declare the efforts of Sultan Idris Education University in this field, especially within issues relate to understanding the Quran, its interpretation, and Islamic Legal Provisions. Keywords: Arabic, Arabic Learning, Islamic provisions 1. Introduction As defined by Al-Ghaliyeni (1993), the Arabic language is all the words Arabs use to name their items, and all the words which were transferred to us. -

Islamic Televangelism: Religion, Media and Visuality in Contemporary Egypt

Islamic Televangelism: Religion, Media and Visuality in Contemporary Egypt YASMIN MOLL In the Egyptian hit film Awqaat Faraagh (Leisure Time, 2006), three young college students experience an existential crisis when one of their friends suddenly dies while crossing the street to buy them more beer. Sitting in a souped-up Mercedes Benz filled with hashish smoke and scantily clad girls, the three boys watch in horror as their friend, high and tripping, is hit by a car and immediately falls to the ground, breathing his last with the words: “I am afraid, I am afraid.” Chastened and shocked by this tragedy, they vow to repent their dissolute lifestyles and lead more moral lives. Instead of watching Internet porn, they begin to download and watch together episodes of a religious talk-show by Amr Khaled, an immensely popular Islamic da’iya (activist, “caller” to Islam), who regularly appears on satellite television. This is an integral part of a strict moral regimen of increased prayers, abstinence from sex, alcohol and cigarettes, and more regular visits to the mosque. Soon, however, with the memory of their friend’s sudden death fading and their own lives no longer seeming so precarious, the three friends tire of this pious leisure. They switch off Khaled’s show and venture once more into Cairo’s glittering nightlife in search of other highs and ways to fill their free time. For the three characters of this film and thousands of other young Egyptians, Amr Khaled’s brand of Islamic televangelism is merely one element – however prominent – of the diffuse and variegated “mediascape” (Appadurai 1996) that marks urban Egypt.