Understanding the Gendered Experiences of Nonbinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tommy Hilfiger and Actor and Activist, Indya Moore Co-Design

TOMMY HILFIGER AND ACTOR AND ACTIVIST, INDYA MOORE CO-DESIGN GENDER FLUID CAPSULE COLLECTION The “TommyXIndya” capsule celebrates the beauty and diversity of the global community with a range of size- inclusive, non-gendered pieces. AMSTERDAM, THE NETHERLANDS (JULY 2021) – Tommy Hilfiger, which is owned by PVH Corp. [NYSE: PVH], announces the launch of the Summer Pre-Fall 2021 TommyXIndya capsule collection co-designed by non-binary actor and activist, Indya Moore. The collection celebrates the uniqueness, beauty and diversity of the global community and the belief that great style knows no boundaries, with a range of size-inclusive, non-gendered designs. The TommyXIndya partnership builds on Tommy Hilfiger’s ambitious People’s Place Program, a three-pillared platform with the mission of advancing representation in fashion and beyond. The TommyXIndya capsule will be available starting July 13th in the US on tommy.com, starting July 20th globally on tommy.com and at select retail locations in Europe. “Great style knows no boundaries, and this has always driven my dream to create fashion for all,” said Tommy Hilfiger. “Our People’s Place Program is a huge step in this direction, as we continue to work hard to advance representation and further inclusivity across all areas of fashion. This collection embodies everything we stand for. From the design process to the campaign, the TommyXIndya partnership is here to make people feel seen, accepted and included. This message means so much to everyone at Tommy Hilfiger. Working with Indya to share their story has been a unique and inspiring experience. We're so proud to share it with the world.” In co-designing the TommyXIndya capsule collection, Indya Moore sought to empower their community to express themselves without limitations. -

The Duke University Student Leadership and Service Awards

The Duke University Student Leadership and Service Awards April 21st, Washington Duke Inn 1 Order of Program Please be seated, we will begin at 6pm Hosts for the Evening Phillip McClure, T’16 Dinner Menu Savanna Hershman, P’17 Salad Baby Field Greens, Poached Pears, Spiced Welcome Walnuts, Champagne Vanilla Dressing Dinner Rolls Freshly Brewed Iced Tea Address by Steve Nowicki, Ph.D. Dean of Undergraduate Education Chicken entrée: Grilled Breast of Chicken, Maple Scented Award Presentations Sweet Potato, Pencil Asparagus, Morel Julie Anne Levey Memorial Leadership Mushroom Sauce Award This meal is free of gluten and dairy Class of 2017 Awards Baldwin Scholars Unsung Heroine Award or Betsy Alden Outstanding Service-Learning Award Vegan entrée: Butternut, Acorn and Spaghetti Squash, Your Three Words Video Golden Quinoa, Arugula, Carrots, Asparagus, Sweet Potato Puree Additional Recognition This meal is free of gluten and dairy Award Presentations Dessert Reception on the Patio Lars Lyon Volunteer Service Award Chocolate Whoopie Pie Trio Leading at Duke Leadership and Service Gourmet Cookies Awards Vegan Dessert: Cashew Cheesecake Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee and William J. Griffith University Service Assorted Hot Tea Award Student Affairs Distinguished Leadership and Service Awards 2 Closing 1 Julie Anne Levey Memorial Leadership Award The Presenters Lisa Beth Bergene, Ph.D. Associate Dean, Housing, Dining and Residence Life Daniel Flowers Residence Coordinator, Southgate and Gilbert-Addoms The Award The -

ESG Report Viacomcbs 2019

ACTIONEnvironmental, Social, and Governance Report ViacomCBS 2019 Introduction Governance On-screen Workforce Sustainable Reporting content and and culture production indices social impact and operations Contents Introduction 3 CEO letter 4 Our approach to ESG 6 About ViacomCBS 9 About this report 10 Our material topics 11 Case study: Responding to a global pandemic 12 Aligning with the UN Sustainable Development Goals 15 Governance 17 ESG governance 19 Corporate governance 20 Data privacy and security 22 Public policy engagement 23 On-screen content and social impact 24 Diverse and inclusive content 26 Responsible content and advertising 31 Using our content platforms for good 33 Expanding our social impact through community projects 35 Workforce and culture 38 A culture of diversity and inclusion 40 Preventing harassment and discrimination 45 Employee attraction, retention, and training 46 Health, safety, and security 48 Labor relations 50 Sustainable production, and operations 51 Climate change 53 Sustainable production 58 Environmental impacts of our operations and facilities 60 Supply chain responsibility 63 Consumer products 66 Reporting indices 68 GRI Index 69 SASB Index 81 COVER IMAGES (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT): CBS, NCIS; CBS Sports; CBS, Super Bowl LIII; CBS News, CBS This Morning ViacomCBS ESG Report 2019 Introduction Governance On-screen Workforce Sustainable Reporting content and and culture production indices social impact and operations Introduction Welcome to our first ESG Report, Action: ESG at ViacomCBS. As we unleash the -

FYE Int 100120A.Indd

FirstYear & Common Reading CATALOG NEW & RECOMMENDED BOOKS Dear Common Reading Director: The Common Reads team at Penguin Random House is excited to present our latest book recommendations for your common reading program. In this catalog you will discover new titles such as: Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, a masterful exploration of how America has been shaped by a hidden caste system, a rigid hierarchy of human rankings; Handprints on Hubble, Kathrn Sullivan’s account of being the fi rst American woman to walk in space, as part of the team that launched, rescued, repaired, and maintained the Hubble Space Telescope; Know My Name, Chanel Miller’s stor of trauma and transcendence which will forever transform the way we think about seual assault; Ishmael Beah’s powerful new novel Little Family about young people living at the margins of society; and Brittany Barnett’s riveting memoir A Knock at Midnight, a coming-of-age stor by a young laer and a powerful evocation of what it takes to bring hope and justice to a legal system built to resist them both. In addition to this catalog, our recently refreshed and updated .commonreads.com website features titles from across Penguin Random House’s publishers as well as great blog content, including links to author videos, and the fourth iteration of our annual “Wat Students Will Be Reading: Campus Common Reading Roundup,” a valuable resource and archive for common reading programs across the countr. And be sure to check out our online resource for Higher Education: .prheducation.com. Featuring Penguin Random House’s most frequently-adopted titles across more than 1,700 college courses, the site allows professors to easily identif books and resources appropriate for a wide range of courses. -

Ballrooms, Voguing, Houses

ANALYSE FPS - 2020 Ballrooms, Voguing, Houses : un bout de culture queer Ballrooms, Voguing, Houses : un bout de culture queer – FPS 2020 Eléonore Stultjens Secrétariat général des FPS Chargée d’études [email protected] Photo de couverture : POSE de BBC/FX Éditrice responsable : Noémie Van Erps, Place St-Jean, 1-2, 1000 Bruxelles. Tel : 02/515.04.01 2 Ballrooms, Voguing, Houses : un bout de culture queer – FPS 2020 Introduction Aujourd’hui être transgenre implique encore une multitude d’obstacles, que ce soit en Belgique ou ailleurs dans le monde1. Ceux-ci peuvent prendre des formes diverses : discrimination à l’emploi, comportements haineux, violences ou encore stigmatisation dans le secteur de la santé2. En tant que mouvement féministe, progressiste et de gauche nous prônons l’égalité dans le respect des identités de genre de chacun·e. Afin d’apporter une pierre à cet édifice de l’inclusion, nous souhaitons visibiliser dans cette analyse la culture spécifique des ballrooms, espaces d’émancipation et de pouvoir. Par ce biais, nous voulons également mettre en lumière les combats des personnes transgenres. Au travers d’une description de la culture des ballrooms dans le contexte étasunien, nous aborderons la problématique de l’appropriation culturelle de la danse voguing. Nous verrons que ce phénomène d’appropriation à des fins commerciales efface les discriminations plurielles et intersectionnelles subies par les communautés latino-noire transgenres et, en même temps, nie complètement les privilèges des américain·e·s blanc·he·s cisgenres. Ensuite, nous ferons un arrêt historique sur les luttes LGBTQIA+ et le combat contre le VIH pour appréhender la façon dont les luttes transgenres sont perçues au sein d’un mouvement plus large, entre des dynamiques d’inclusion et d’exclusion. -

Saturday Church

SATURDAY CHURCH A Film by Damon Cardasis Starring: Luka Kain, Margot Bingham, Regina Taylor, Marquis Rodriguez, MJ Rodriguez, Indya Moore, Alexia Garcia, Kate Bornstein, and Jaylin Fletcher Running Time: 82 minutes| U.S. Narrative Competition Theatrical/Digital Release: January 12, 2018 Publicist: Brigade PR Adam Kersh / [email protected] Rob Scheer / [email protected] / 516-680-3755 Shipra Gupta / [email protected] / 315-430-3971 Samuel Goldwyn Films Ryan Boring / [email protected] / 310-860-3113 SYNOPSIS: Saturday Church tells the story of 14-year-old Ulysses, who finds himself simultaneously coping with the loss of his father and adjusting to his new responsibilities as man of the house alongside his mother, younger brother, and conservative aunt. While growing into his new role, the shy and effeminate Ulysses is also dealing with questions about his gender identity. He finds an escape by creating a world of fantasy for himself, filled with glimpses of beauty, dance and music. Ulysses’ journey takes a turn when he encounters a vibrant transgender community, who take him to “Saturday Church,’ a program for LGBTQ youth. For weeks Ulysses manages to keep his two worlds apart; appeasing his Aunt’s desire to see him involved in her Church, while spending time with his new friends, finding out who he truly is and discovering his passion for the NYC ball scene and voguing. When maintaining a double life grows more difficult, Ulysses must find the courage to reveal what he has learned about himself while his fantasies begin to merge with his reality. *** DAMON CARDASIS, DIRECTOR STATEMENT My mother is an Episcopal Priest in The Bronx. -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

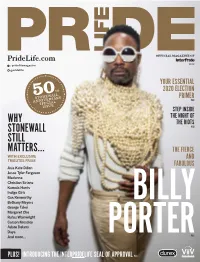

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Parents and Caregivers As Sexuality

Parents and Caregivers as Sexuality Educators Small Group Ministry Sessions By Robin Slaw Susan Dana Lawrence, Developmental Editor © Unitarian Universalist Association, 2019 Based on a field-tested program written by Karen Rayne and edited by Melanie Davis Introduction Welcome to a program for Unitarian Universalist parents and caregivers who seek support and skills to be effective sexuality educators of their children. This program invites adults to ask themselves: How can I embody my role as my child’s primary sexuality educator in a way that expresses my UU values and faith? Of course, children pick up information and attitudes from sources beyond the home: peers, popular culture, social media, other adults. Many Unitarian Universalist children will participate in Our Whole Lives (OWL), the lifespan, holistic, values-based sexuality education program provided by the Unitarian Universalist Association and the United Church of Christ, and they may also receive sexuality education in school. However, OWL encourages, and this program aims to nurture, parents and caregivers in their role as their children’s primary sexuality educators. Trusted adults carry extraordinary power to influence their children’s attitudes and values around sexuality. Many adults struggle to wield that power with intentionality, grace, and confidence. These sessions invite parents and caregivers to find support, insight, and courage with one another. While the small group ministry format provides a spiritually grounded space, the program’s approach to sexuality is secular and grounded in science, in tune with the OWL lifespan sexuality education programs on which it is based. A facilitator can bring this program to a secular setting by omitting references to Unitarian Universalist Principles and values. -

A National Epidemic: Fatal Anti-Transgender Violence in the United States in 2019 from President Alphonso David

A NATIONAL EPIDEMIC: FATAL ANTI-TRANSGENDER VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED STATES IN 2019 FROM PRESIDENT ALPHONSO DAVID At this moment, transgender women of color are living in crisis. Over the past several years, more than 150 transgender people have been killed in the United States, nearly all of them Black transgender women. At the time of publication of this report, we advocates who have been doing this work for know of at least 22 transgender and gender decades to provide additional support, advance non-conforming people who have been killed programs and ultimately change systems to this year in this country. drive long-term change across this country. With our partners, we are working to support While the details of the cases differ, it is clear advocates through capacity building, leverage that the intersections of racism, sexism and our strengths with our corporate and community transphobia conspire to deny so many members partners to deliver new economic and training of the transgender community access to opportunities, and work with local governments housing, employment and other necessities to to drive systematic change in areas most survive and thrive. needed – public safety, healthcare, housing, education and employment. As the stories documented in this report make clear, this is a national crisis that demands the This is urgent work — and it requires all of us attention of lawmakers, law enforcement, the to engage. In this report, the Human Rights media and every American. Campaign’s team of researchers, policy experts and programmatic specialists have For transgender women of color who are living laid out steps that every person can take to in crisis, their crisis must become our crisis help eliminate anti-transgender stigma, remove as well. -

Representações Da Performatividade LGBTQ+ No Audiovisual a Partir Do Seriado Pose (2018)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA INSTITUTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO Olávio Bento Costa Neto Queerness em tela: representações da performatividade LGBTQ+ no audiovisual a partir do seriado Pose (2018) UBERLÂNDIA 2020 OLÁVIO BENTO COSTA NETO Queerness em tela: representações da performatividade LGBTQ+ no audiovisual a partir do seriado Pose (2018) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Linha de pesquisa: História e Cultura Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Mônica Brincalepe Campo 04/12/2020 SEI/UFU - 1861490 - Ata de Defesa - Pós-Graduação UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Av. João Naves de Ávila, 2121, Bloco 1H, Sala 1H50 - Bairro Santa Mônica, Uberlândia-MG, CEP 38400-902 Telefone: (34) 3239-4395 - www.ppghis.inhis.ufu.br - [email protected] ATA DE DEFESA - PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO Programa de Pós-Graduação História em: Defesa de: DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO, Ata 4, PPGHI Dezenove de fevereiro de dois Hora de Data: Hora de início: 16:00 17h28 mil e vinte encerramento: Matrícula do 11812HIS014 Discente: Nome do Olávio Bento Costa Neto Discente: Título do Queerness em tela: representações da performavidade LGBTQ+ no audiovisual a parr do seriado Trabalho: Pose (2018) Área de História Social concentração: Linha de História e Cultura pesquisa: Projeto de Narravas Subjevas: a memória, a história e o discurso em primeira pessoa nas narravas Pesquisa de cinematográficas vinculação: Reuniu-se na Sala 48, Bloco 1H - Campus Santa Mônica, da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, a Banca Examinadora, designada pelo Colegiado do Programa de Pós-graduação em História, assim composta: Professores Doutores: Reinaldo Maximiano Pereira (UFU), Sabina Reggiani Anzuategui (FACASPER - parcipou via SKYPE), Mônica Brincalepe Campo orientadora do candidato. -

Download (560Kb)

University of Huddersfield Repository Yeadon-Lee, Tray Remaking Gender: Non-binary gender identities Original Citation Yeadon-Lee, Tray (2017) Remaking Gender: Non-binary gender identities. In: Non-Binary Genders, 8th September 2017, Open University, London. (Unpublished) This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/33201/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Remaking Gender: Non-binary gender identities Dr Tray Yeadon-Lee University of Huddersfield [email protected] The Research • How are NB identities being lived and established in everyday life? • What are the everyday challenges and how are these negotiated and overcome? • Currently: increasing visibility of NB identities in popular media