Supplementum 4 S Kazalom Section Head

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number 2, Spring 2004

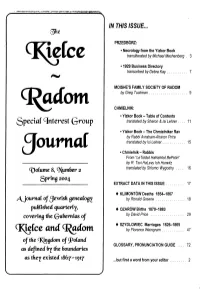

IN THIS ISSUE... PRZEDBÔRZ: • Necrology from the Yizkor Book transliterated by Michael Meshenberg . 3 • 1929 Business Directory transcribed by Debra Kay 7 MOISHE'S FAMILY SOCIETY OF RADOM by Greg Tuckman 9 CHMIELNIK: • Yizkor Book - Table of Contents Speciaf interest Group translated by Sharon & Isi Lehrer.... 11 • Yizkor Book - The Chmielniker Rav by Rabbi Avraham-Aharon Price ^journal translated by Isi Lehrer 15 •Chmielnik-Rabbis From "LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin" by R. Tsvi HaLevy Ish Hurwitz 8, (]>{um6er 2 translated by Shlomo Wygodny 16 gpring 2004 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 17 • KLIMONTÔW Deaths 1854-1867 ^\ journaf oj £Jewish geneafog^ by Ronald Greene 18 puBfishetf quarterly, • OZARÔW Births 1870-1883 covering the (JuBernias oj by David Price 29 ancf • SZYDLOWIEC Marriages 1826-1865 of the ^Kingdom oftpoland by Florence Weingram 47 as defined 6^ the Boundaries GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE .... 72 as they existed 1867-1917 ...but first a word from your editor 2 Kielce-Radom SIG Journal Volume 8, Number 2 Spring 2004 ... but first a word from our editor In this issue, we have information about the towns of Przedbôrz and Chmielnik. For Przedbôrz - a transliteration of the Special (Interest GrouP names of the Holocaust martyrs from the 1977 Przedbôrz Yizkor Book Przedborz - 33 shanim; and a transcript of the Przedbôrz cjournaf entries from the 1929 Polish Business Directory. ISSN No. 1092-8006 For Chmielnik - a translation of the extensive Table of Contents and a short article from the 1960 Yizkor Book Pinkas Published quarterly, Chmielnik: Yisker bukh noch der Khorev-Gevorener Yidisher in January, April, July and October, by the Kehile; and an article about Chmielnik rabbis translated from KIELCE-RADOM LeToldot HaKehilot BePolin. -

Twenty Payment Life Policy the MASSACHUSETTS

II ADVERTISEMENTS A SAFE INVESTMENT FOR YOU Did you ever try to invest money safely? Experienced Financiers find this difficult: How much more so an inexperienced person. ...THE... Twenty Payment Life Policy (With its Combined Insurance and Endowment Features) ISSUED By THE MASSACHUSETTS MUTUAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, OF SPRINGFIELD, MASS. is recommended to you as an investment, safe and profitable. The Policy is plain and simple and the privileges and values are stnted in plain figures that any one can read. It is a sure and systematic way of saving money for your own use or support in later years. Saving is largely a matter of habit. And the semi-compulsory feature cultivates that saving habit. Undir the contracts issued by the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insur- ance Company the protection afforded is unsurpassed. For further information address HOME OFFICE, Springfield, Mass., or New York Office, Empire Building, 71 Broadway. PHILADELPHIA OFFICE, - - - Philadelphia Bourse. BALTIMORE " 4 South Street. CINCINNATI " - Johnston Building. CHICAGO " Merchants Loan and Trust Building. ST. LOUIS " .... Century Building. ADVERTISEMENTS III 1851, 1901. The Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company, of Hartford, Connecticut, Issues Endowment Policies to either men or women, which (besides.giving Five other options) GUARANTEE when the Insured is Fifty, Sixty, or Seventy Years Old To Pay $1,500 in Cash for Every $1,000 of Insurance in force. Sample Policies, rates, and other information will be given on application to the Home Office. ¥ ¥ ¥ JONATHAN B. BUNCE, President. JOHN M. HOLCOMBE, Vice-President. CHARLES H. LAWRENCE, Secretary. MANAGERS: WEED & KENNEDY, New York. JULES GIRARDIN, Chicago. H. W. -

Moses Mendelssohn and the Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18Th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families

Moses Mendelssohn and The Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families To be given at the Conference of Jewish Genealogy in London 2001 By Michael Honey I have drawn nine diagrams by the method I call The Jewish Historical Clock. The genealogy of the Mendelssohn family is the tenth. I drew this specifically for this conference and talk. The diagram illustrates the intertwining of relationships of Rabbi families over the last 600 years. My own family genealogy is also illustrated. It is centred around the publishing of a Hebrew book 'Megale Amukot al Hatora' which was published in Lvov in 1795. The work of editing this book was done from a library in Brody of R. Efraim Zalman Margaliot. The book has ten testimonials and most of these Rabbis are shown with a green background for ease of identification. The Megale Amukot or Rabbi Nathan Nata Shpiro with his direct descendants in the 17th century are also highlighted with green backgrounds. The numbers shown in the yellow band are the estimated years when the individuals in that generation were born. For those who have not seen the diagrams of The Jewish Historical Clock before, let me briefly explain what they are. The Jewish Historical Clock is a system for drawing family trees ow e-drmanfly 1 I will describe to you the linkage of the Mendelssohn family branch to the network of orthodox rabbis. Moses Mendelssohn 1729-1786 was in his time the greatest Jewish philosopher. He was one of the first Jews to write in a modern language, German and thus opened the doors to Jewish emancipation so desired by the Jewish masses. -

Dubrovnik Annals 2 (1998) Reviews Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations

Dubrovnik Annals 2 (1998) 109 Reviews inquiry. A petty reader is likely to observe that his references and bibliography do not Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations: Jews include works in some European languages, and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern German for example. However, one must not Mediterranean. Leiden - New York - KOln, fail to discern a number of references in Eng 1995 lish, French, Italian as well as those of medi eval origin. His sources deserve even greater In the history of the Mediterranean, the credit. Arbel emerges here as a scholar wor year 1571 witnessed several most tragic thy of every praise, and an experienced ar events. On 5 August, Famagusta, the so chival researcher who has discovered a vereign city of Cyprus, was besieged by the number of valuable documents (see below) forces of the Ottoman Turks led by Sultan for which he should be given the most credit. Selim II, and on 7 October, the allied Chri A brief look at the structure of the study stian fleet under the command of Don Juan unfolds another of this author's qualities: he of Austria defeated the Turks in the naval takes great concern in human destinies. Arbel battle of Lepanto. While the great armies centers upon man, the individual, his mental clashed and the winds of war prevailed pattern and looks, and his environment. This throughout the European continent, an event aspect of his work is evident in the earlier of different nature took place in the Venetian studies,2 but also in his latest book, in which Republic: on 18 December it was decreed he inclines toward the medievalistics of the that all the Jews residing within the Repub day. -

Cervantes, Cyprus, and the Sublime Porte: Literary Representations of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Jew Solomon Ashkenazi

Michael Gordon 205 Cervantes, Cyprus, and the Sublime Porte: Literary Representations of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Jew Solomon Ashkenazi Michael Gordon University of Wisconsin–Madison The aim of this study is to explore, with particular attention given to Ottoman Jewish subjects, Cervantes’ recreations of the political and economic realities of eastern Mediterranean societies in El amante liberal (AL) and La gran sultana (GS).1 Ottmar Hegyi (1998) thoroughly details and challenges the different treatment that the aforementioned works have been given by critics in comparison to that given to Cervantes’ North African captivity plays, El trato de Argel (TA) and Los baños de Argel (BA).2 Although the merits of Hegyi’s observation connecting AL and GS will be discussed later in this paper, it is necessary to first establish that these two works are also bound by their chronological and geographical settings, both of which are related to seminal historical events that, although they occurred in the 1570s, were still relevant to the 17th- century Spanish public. In the case of AL, the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus figures prominently, while in GS, Ottoman relations with Persia and Spain, as well as Spain’s military operations in Flanders, are constantly referenced. More immediately relevant to Ottoman Jews,3 however, were the social, political and economic environments of Cyprus and Istanbul that gave them extensive freedom of movement and access to the sultan’s court. The Jew Solomon Ashkenazi, who served not only as the Venetian Bailo’s physician in Istanbul and then as an advisor to the Ottoman Grand Vizier Sokollu, but who was also active in Mediterranean commerce, took advantage of those favorable circumstances. -

Of This Volume One Hundred Copies Ha Ve Been

fwm rb s mm é am u e l j am ily CO LLEC TED FRO M ESSAY S MSS. AND OTHER SO URCES ’ D A MU EL J . B U N FO R S WITH ILLUSTRA TIONS !Brita i n for abtihate mu tilation Y B LI I OMPA Y ILA LP IA B J . PP NCCYIT C N , PH DE H MCM! II 1 3 B ? . EWOI m un . COPY RIGHT 91 . I D AT T“ WASHINGTON S! UARE PRE S PHILADELPHIA. 11. 8v “ I a l l 1 21” C0aunts PA “ S M PA m LY N N HE KA B NB L RECORD or THE SA UEL , I CLUDI G T TZ B N II A ND a cnzzs n on r m ; LA 'rzs 'r A ns DO C N SAMUEL , cc s M S B . IDLE SS. ON THE U JECT ’ EDzLu A NN s 'rO Iu r WA IIL IL ' ' ' N S WII IL A PORTION or or SAUL , Ta n: V n B . S Fno MS. or MARCU AND SON, or IENNA A WS K N P B Y G S V KA RPELES . JE I H I G IN OLAND, U TA E W n on WS Y P . SAUL AHL, THE JE I H ENC CLO EDIA — A KING Iron A NIGHT THE PO LIs II s WIIO REIGNED VI WA s s U C WA IIL B Y REV . zu SAUL , DA D ‘ Lu BY S . Sn rcn or REB ECCA AD , MARCU ADLER l ist of fi lm s PA I F Y W DY . -

1 Comparative Legal Histories Workshop

Department of Sociology Comparative Legal Histories Workshop: Colonial/Postcolonial India and Mandatory Palestine/Israel Stanford Law School Faculty Lounge June 6, 2011 Description In recent years, an impressive body of scholarship has emerged on colonial legal history. Some of this work has focused on Indian and Israeli legal history. While both contemporary Indian and Israeli law are in some senses a product of English law, many additional legal sources, including religious and customary law, have played a significant role in shaping the corpus of law in both countries. This history has yielded complex pluralistic legal orders which faced, and still face, similar problems, including the ongoing effects of the British colonial legacy and postcolonial partition, tensions between secularism and religion, and also the desire to absorb universalizing western culture while maintaining some elements of tradition. The goal of our workshop is to bring together a group of legal historians interested in comparative colonial histories who are studying different aspects of the history of Indian and Israeli law. The workshop will be a one-day informal gathering that would combine a discussion of trends in comparative colonial legal history with an opportunity for participants to present their research projects. Our objective is to create a forum where legal historians who may not necessarily be in dialogue with one another can interact, exchange ideas, and perhaps even begin collaborative research projects. The workshop is organized by Assaf Likhovski (Tel Aviv University) Renisa Mawani (UBC) and Mitra Sharafi (UW Law School). It is funded by the David Berg Institute for Law and History at Tel Aviv University, the Institute for Legal Studies, University of Wisconsin Law School, and the Department of Sociology at the University of British Columbia, and hosted by Stanford Law School. -

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: a Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust

The Transfer Agreement and the Boycott Movement: A Jewish Dilemma on the Eve of the Holocaust Yf’aat Weiss In the summer of 1933, the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the German Zionist Federation, and the German Economics Ministry drafted a plan meant to allow German Jews emigrating to Palestine to retain some of the value of their property in Germany by purchasing German goods for the Yishuv, which would redeem them in Palestine local currency. This scheme, known as the Transfer Agreement or Ha’avarah, met the needs of all interested parties: German Jews, the German economy, and the Mandatory Government and the Yishuv in Palestine. The Transfer Agreement has been the subject of ramified research literature.1 Many Jews were critical of the Agreement from the very outset. The negotiations between the Zionist movement and official representatives of Nazi Germany evoked much wrath. In retrospect, and in view of what we know about the annihilation of European Jewry, these relations between the Zionist movement and Nazi Germany seem especially problematic. Even then, however, the negotiations and the agreement they spawned were profoundly controversial in broad Jewish circles. For this reason, until 1935 the Jewish Agency masked its role in the Agreement and attempted to pass it off as an economic agreement between private parties. One of the German authorities’ principal goals in negotiating with the Zionist movement was to fragment the Jewish boycott of German goods. Although in retrospect we know the boycott had only a marginal effect on German economic 1 Eliahu Ben-Elissar, La Diplomatie du IIIe Reich et les Juifs (1933-1939) (Paris: Julliard, 1969), p. -

Review Essay

Studia Judaica (2017), Special English Issue, pp. 117–130 doi:10.4467/24500100STJ.16.020.7372 REVIEW ESSAY Piotr J. Wróbel Modern Syntheses of Jewish History in Poland: A Review* After World War II, Poland became an ethnically homogeneous state. National minorities remained beyond the newly-moved eastern border, and were largely exterminated, forcefully removed, or relocated and scattered throughout the so-called Recovered Territories (Polish: Ziemie Odzys kane). The new authorities installed in Poland took care to ensure that the memory of such minorities also disappeared. The Jews were no exception. Nearly two generations of young Poles knew nothing about them, and elder Poles generally avoided the topic. But the situation changed with the disintegration of the authoritarian system of government in Poland, as the intellectual and informational void created by censorship and political pressure quickly filled up. Starting from the mid-1980s, more and more Poles became interested in the history of Jews, and the number of publica- tions on the subject increased dramatically. Alongside the US and Israel, Poland is one of the most important places for research on Jewish history. * Polish edition: Piotr J. Wróbel, “Współczesne syntezy dziejów Żydów w Polsce. Próba przeglądu,” Studia Judaica 19 (2016), 2: 317–330. The special edition of the journal Studia Judaica, containing the English translation of the best papers published in 2016, was financed from the sources of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education for promotion of scientific research, according to the agreement 508/P-DUN/2016. 118 PIOTR J. WRÓBEL Jewish Historiography during the Polish People’s Republic (PRL) Reaching the current state of Jewish historiography was neither a quick nor easy process. -

Piotr S. Szlezynger the JEWISH QUARTER in NOWY WIŚNICZ

SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA * Vol. 9 Kraków 2011 Piotr S. Szlezynger THE JEWISH QUARTER IN NOWY WIŚNICZ The former Jewish quarter (16th to 20th century) of Nowy Wiśnicz (henceforth: Vischnitsa) has so far only been mentioned on a few occasions and ווישניצא .Wiśnicz, Yid with little precision, in the books by Stanisław Fischer (1927/28), Mieczysław Książek (1976, 1979, 1988, 1990), and Adam Bartosz (1992). The last decades saw a handful of publications regarding this subject. The first one to touch upon it was Iwona Zawidzka, who described the cemetery and gave a brief account of the town’s history. She was followed by Elżbieta Ostrowska, who focused on relations between Christian and Jew- ish inhabitants of the town from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Adam Bartosz, Stanisław Fischer, Mieczysław Książek and Iwona Zawidzka incorrectly ascribed the lack of any photographic record of both synagogues and the public buildings to having been de- molished by Germans during the Nazi occupation. I. Zawidzka1 mentions an essay by Julia Goczałkowska2 in which the author describes what she refers to as the Wiśnicz “Jerusalem.” The present article is an extended and improved version of an earlier publication, originally printed in the Architectural and Town Planning Quarterly.3 The author re- turned to this matter after having obtained new information and having conducted ad- ditional research in archives but firstly and fore mostly in the field. This research allowed for an in-depth analysis of source and photographic materials as well as for an attempt -

Claims Resolution Tribunal

CLAIMS RESOLUTION TRIBUNAL In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation Case No. CV96-4849 Certified Award to Claimant [REDACTED 1] to Claimant [REDACTED 2] and to Claimant [REDACTED 3] in re Account of Max Lengsfelder Claim Numbers: 150143/HB; 150144/HB; 150145/HB Award Amount: 49,375.00 Swiss Francs This Certified Award is based upon the claims of [REDACTED 1], née [REDACTED], ( Claimant [REDACTED 1] ), [REDACTED 2] ([REDACTED]) ( Claimant [REDACTED 2] ), and [REDACTED 3], née [REDACTED] ([REDACTED]) ( Claimant [REDACTED 3] ) (together the Claimants ) to the published account of Max Lengsfelder (the Account Owner ), over which Olga Lengsfelder (the Power of Attorney Holder ) held power of attorney, at the Zurich branch of the [REDACTED] (the Bank ). All awards are published, but where a claimant has requested confidentiality, as in this case, the names of the claimants, any relatives of the claimants other than the account owner, and the bank have been redacted. Information Provided by the Claimants The Claimants each submitted Claim Forms indicating that they are siblings and identifying the Account Owner as their paternal grandfather, Dr. Med. Max (Maximilian) Lengsfelder, who was born on 27 November 1877 in Austria-Hungary (later Czechoslovakia), and was married to Olga Lengsfelder, née Stern, who was born on 1 August 1882. According to the Claimants, their grandparents, who were Jewish, resided in Kratzau (Chrastava), Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), where their grandfather was a medical doctor and owned a medical clinic, a dental clinic, and several buildings. The Claimants indicated that their grandparents had two children: [REDACTED], who was born in 1905 in Kratzau and died childless in 1928, and [REDACTED] (the Claimants father), who was born on 22 October 1914 in Kratzau. -

In 1949, Moshe Ben-David, Then 22 Years Old and Already An

In 1949, Moshe Ben-David, then 22 years old and already an established jewelry maker by family tradition, immigrated from his ancestral home in Southern Yemen to the year-old State of Israel. His personal migration, part of a larger wave influenced by a Zionist zeal, was initiated and carried out by the Israeli government and the Jewish Agency that feared for the well-being of the community (Ben Zvi, 1949). The Jewish exodus from Yemen was sparked by the rising tides of nationalism, a political backlash to the failure of the Palestinian cause, and an anti- Semitic sentiment that had flared in the 1947 Aden riots. The perceived sense of immediate threat to the well-being of the community gave way to a decision to transport people to Israel as quickly as possible. The exodus from Yemen—simultaneously conducted in Iraq and subsequently in Iran, Morocco, and the majority of the Arab world—meant hastily leaving without gathering belongings, cultural artifacts, personal records, and documents. As people rushed from city centers to transitory and refugee camps, to makeshift airports, they carried only what they could. It is almost unfathomable that the flourishing Jewish Yemeni community—one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, deeply entrenched in its territory, and holding a unique cultural and religious tradition—had all but disappeared in less than a year. Ancient Torah books, musical instruments, photographs, personal letters, heirloom rugs, silver, jewelry, and furniture were left behind, lost in transportation, or sold to fund a new beginning, causing a massive loss of community heritage and cultural knowledge (Meir-Glitzenstein, 2015, p.