Rewriting History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acorn User Display at the AAUG Stand During Will Be Featuring Denbridge Digital the RISC OS '99 Show at Epsom Race in More Depth in a Future Issue of the Course

eD6st-§elling RISC OS magazine in the world 4^:^^ i I m Find out what Rf| ::j!:azj achines can do tau ISSUE 215 CHRISTMAS 1999 £4.20 1 1 1 1 1! House balls heavy (packol 10) £15 illSJ 640HS Media lot MO dri.c £|9 £!2J]| Mouse lor A7000/r- N/C CD 630t1B re-wriie niedia £10 fii.rs £S tS.il Mouse for all Aciirns (not etr) A70DQ CD 630MB vrriie once raedis (Pk ol Computers for Education £12 II4.II1 10) £|0 £11.15 Original mouse for all Atoms (not A7K) HARDWARE i £16 urn JAZ IGB midta £58 £68.15 Business and Home |AZ 2GB media PERIPHERALS £69 [i PD 630MS media SPECIAL OFFER! £18 tll.lS I Syid 1.5GB media £S8 £S!IS ISDN MODEM + FREE Syquest lOSMB media £45 [S28I ACORN A7000+ tOHniTERS FIXING K. SytfuestOiMB media £45 islSjl INTERNET CONNEaiON )f[|iit'iij![IMB media £45 tS2S slice lor ,!.:., 2d Rlst PC int 1 waj L jj) i( 1 Syqufit 770HB media £76 £45 (Sji? I A?000 4. Ciasm [D £499 hard drive liting kir 2x 64k bpi ehaniiels mil M IDE £|2 £14.10 Zip lOOHBraetfia £8 (Ml IS9xU0«40mm A7000+(l3isnhO £449 W.il i- baikplane (not il CO aJrody insialled) Zip mW £34 [3).!S iOOMB media 1; pack) £35 awl] ;;! footprint A71100+0(lyHeyCD £549 mil Fixing km for hard drives ^ £S ff.40 Zip2S0HBmedia £11.50 (I4.i .Wf^ »«* 2 analogue ports |aTODCH- Odysse)- Nmotk HoniiDr cable lor all £525 mm Acorn (lelecdon) £|0 fll iS | 30 I- Odyssey Primary £599 flOJ ai Podule mi lor A3D00 £|6 RISC OS UPGRADES 47000 I OdyssEc Setoiidary £599 Rise PC I slo[ backplane ISP trial mm ii4.B I Argonet I £29 A700Oi Rise OS 3.11 chip sti £20 am OdyssEr^uil £699 Lih.il SCSI I S II [abteclioice -

Show Special

The magazine for members of SHOW SPECIAL SE Show ARM Club Midlands Show USB on RISC OS Issue 52 — Winter 2005 What's in a name? RISC OS or Risc OS? Does it answer now? Not to be confused matter. After all it’s just a name, with Risc OS which is a name of isn’t it? This sort of dialogue another operating system! usually crops up once a year on comp.sys.acorn.misc. user group Using the correct name and after some poor devil has typed it definition for things is very incorrectly and the wrath of Druck important, just like using correct and others falls upon them causing English - grammar and spelling - them to quake in their boots and otherwise misunderstandings can promise never to transgress again. occur. A good example was an This generally then sets off argument on AOL (you have to be argument on whether it matters or careful here, it’s not what you not, which is normally good for a think, in this case it stands for few hundred posts and a few laughs. Archive On Line) about what the It comes round fairly frequently, term ‘optical zoom’ really meant. just like top posting, so you would This kept me amused over several have thought most people would weeks. Just as well it was on email, have got it right by now. if the two main protagonists had actually met face to face the So which one is correct? Do you RISC OS community would have know? Answers on a post card, I’m lost half it’s members! afraid no prizes except for a mention in dispatches. -

![Frobnicate@Argonet.Co.Uk]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0022/frobnicate-argonet-co-uk-730022.webp)

[email protected]]

FUN FUN FUN ’TIL DADDY TOOK THE KEYBOARD AWAY!!! • VILLAGE LIFE IN INDIA • ASSEMBLER THE ACORN CODE AND MORE!!! Summer 1997 Issue 14 £0 123> Index: Page 2 . Index. Page 3 . Editors Page. Page 4 . Village Life In India. Page 6 . Assembler programming. Page 12 . Econet - a deeper look. Page 13 . Diary of a demented hacker. Page 14 . DIGIWIDGET. Page 15 . Argonet (#2). Page 16 . Update to Acorn machine list. Page 19 . The Acorn Code Credits: Editor . Richard Murray [[email protected]] Contributors . Richard Murray. Village Life article by Ben Hartshorn. Machine List by Philip R. Banks. Acorn Code by Quintin Parker. Graphics . Richard Murray. Village Life graphics by Ben Hartshorn. You may print and/or distribute this document provided it is unaltered. The contents of this magazine are © Richard Murray for legal reasons. All copyrights and/or trademarks used are acknowledged. Opinions stated are those of the article author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Frobnicate, BudgieSoft or Richard Murray. All reasonable care is taken in the production of this magazine, but we will not be legally liable for errors, or any loss arising from those errors. As this magazine is of a technical nature, don’t do anything you are unsure of. Reliance is placed in the contents of this magazine at the readers’ own risk. Frobnicate is managed by “Hissing Spinach”, the publishing division of BudgieSoft UK. Comments? Submissions? Questions? [email protected] Or visit our web site (as seen in Acorn User)... http://www.argonet.co.uk/users/rmurray/frobnicate/ FROBNICATE ISSUE 14 - Summer 1997 Page 3 EDITORS PAGE This issue has seen a few changes. -

Acorn User 1986 Covers and Contents

• BBC MICRO ELECTRON’ATOMI £1.20 EXJANUARY 1986 USB* SPECTRAIYIANIA: Zippy game for Electron and BBC LOGO SOFTWARE: Joe Telford writes awordprocessor HyfHimm,H BBC B+ PROGRAMS: Our advanced HdlilSIii t user’s guide mm BASIC AIDS: pjpifjBpia *- -* ‘‘.r? r v arwv -v v .* - The hard facts about debuggers WIN AT ELITE: Secrets of the Commander files SUPER Forget the rest, our graphics program’s best! COMPETITION Three Taxan monitors to be won COUPON OFFER Save £20 on a Kaga NLQ printer ISSUEACORNUSERNo JANUARY 1986 42 EDITOR Tony Quinn NEW USERS 48 TECHNICAL EDITOR HINTS AND TIPS: Bruce Smith Martin Phillips asks how compatible are Epson compatible printers? 53 SUBEDITOR FIRST BYTE: Julie Carman How to build up your system wisely is Tessie Revivis’ topic PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Kitty Milne BUSINESS 129 EDITORIAL SECRETARY BUSINESS NEWS: Isobel Macdonald All the latest for users of Acorn computers in business, plus half-price Mallard Basic offer PROCESS: 133 TECHNICAL ASSISTANT WHICH WORD TO David Acton Guidelines from Roger Carus on choosing a wordprocessor to fulfil your business needs 139 ART DIRECTOR BASIC CHOICES: Mike Lackersteen Edward Brown compares BBC Basic and Mallard Professional Basic, supplied with the Z80 ART EDITOR Liz Thompson EDUCATION EDUCATION NEWS: 153 ART ASSISTANT questions Paul Holmes Proposed European standard for educational micros raises many OF WORDPROCESSING: 158 ADVERTISEMENT MANAGER THE WONDER Simon Goode Chris Drage and Nick Evans look at wordprocessors to help children express themselves j SALES EXECUTIVE j ; -

Acorn User March 1983, Number Eight

ii[i: lorn hardware conversion Vinters: a layman's guide Micros and matlis Atom with BBC Basic Beeb sound the C mic ' mputers veri mes T^yT- jS Sb- ^- CONTENTS ACORN USER MARCH 1983, NUMBER EIGHT Editor 3 News 67 Atom analogue converter Tony Quinn 4 Caption competition Circuitry and software by Paul Beverley Editorial Assistant 71 BBC Basic board Milne 8 BBC update Kitty Barry Pickles provides a way round David Allen describes some Managing Editor some of its limitations Jane Fransella spin-offs from the TV series Competition Production 11 Chess: the big review 75 Simon Dally offers software for Peter Ansell John Vaux compares three programs TinaTeare solving his puzzler with a dedicated machine Marketing Manager 15 Beeb forum 79 Book reviews Paul Thompson Assembly language and Pascal Ian Birnbaum on programming Promotion Manager among this month's offerings Pal Bitton 19 Musical synthesis 83 Printers for beginners Publisher Jim McGregor and Alan Watt assess First part of this layman's guide Stanley Malcolm the Beeb's potential by George Hill Designers and Typesetters 27 DIYIightpen GMGraphics, Harrow Hill 89 Back issues and subscriptions Joe Telford shows you how in a Graphic Designer to get the ones you missed, and hardware session of Hints and Tips How Phil Kanssen those you don't want to miss in Great Britain 33 Lightpen OXO Printed 91 Letters by ET.Heron & Co. Ltd Software from Joe Telford Readers' queries and comments on Advertising Agents Lightpen multiple choice 39 everything from discs to EPROMs Computer Marketplace Ltd 41 BBC assembler 20 Orange Street 95 Official dealer list London WC2H 7ED Tony Shaw and John Ferguson Where to go for the upgrades 01-930 1612 addressing tackle indirect and support Distributed to News Trade the 45 Micros in primary schools by Magnum Distribulion Ltd. -

BEEBUG for Languages Other Than Basic Would Certainly Be of Interest to Us

£ 1 . 0 0 LARGE Vol 2 No 8 JAN/FEB 1984 DIGITAL DISPLAY DANCING LINES PLUS * DISASSEMBLER MACHINE CODE * PROTECTING GRAPHICS PROGRAMS * FORTH INTRODUCTION * DOUBLE DENSITY DFS REVIEWS * GRAPHICS TABLETS REVIEWED BLOCK BLITZ * And much more BRITAIN'S LARGEST COMPUTER USER GROUP MEMBERSHIP EXCEEDS 20,000 2 EDITORIAL THIS MONTH'S MAGAZINE In this issue, we publish the first part of a new series introducing machine code graphics, which is the basis for the superb screen displays of many of the good commercial games now on the market. The series will introduce many of the techniques involved and will also show you how to include these routines in your Basic programs. We are also very enthusiastic about Block Blitz, one of the very best games written in Basic that we have seen for some time. The effort of typing this into your micro is well worthwhile. We have also included a detailed review of the two double density disc controllers that have so far been released. Apart from the many other excellent programs and articles this month, we have provided a short introduction to the computer language FORTH, as a prelude to a comparative review of FORTH implementations for the BBC micro, that we shall be publishing in the next issue. Your views on the extent to which we should cater in BEEBUG for languages other than Basic would certainly be of interest to us. O.S. 1.2 May I just remind you, for one more time, that this is the last issue of the magazine for which we will be testing all programs with both O.S. -

Acorn User Welcomes Submissions Irom Readers

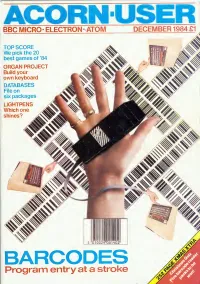

ACORN BBC MICRO- ELECTRON- ATOM DECEMBER 1984 £1 TOP SCORE We pick the 20 best games of '84 ORGAN PROJECT Build your own keyboard DATABASES File on six packages LIGHTPENS Which one shines? Program entry at a stroke ' MUSIC MICRO PLEASE!! Jj V L S ECHO I is a high quality 3 octave keyboard of 37 full sized keys operating electroni- cally through gold plated contacts. The keyboard which is directly connected to the user port of the computer does not require an independent power supply unit. The ECHOSOFT Programme "Organ Master" written for either the BBC Model B' or the Commodore 64 supplied with the keyboard allows these computers to be used as real time synth- esizers with full control of the sound envelopes. The pitch and duration of the sound envelope can be changed whilst playing, and the programme allows the user to create and allocate his own sounds to four pre-defined keys. Additional programmes in the ECHOSOFT Series are in the course of preparation and will be released shortly. Other products in the range available from your LVL Dealer are our: ECHOKIT (£4.95)" External Speaker Adaptor Kit, allows your Commodore or BBC Micro- computer to have an external sound output socket allowing the ECHOSOUND Speaker amplifier to be connected. (£49.95)' - ECHOSOUND A high quality speaker amplifier with a 6 dual cone speaker and a full 6 watt output will fill your room with sound. The sound frequency control allows the tone of the sound output to be changed. Both of the above have been specifically designed to operate with the ECHO Series keyboard. -

FROBNICATE ISSUE 10 — Autumn 1996 Page 4 Point•five•Decade Welcome to a Look Back

FUN FUN FUN ’TIL DADDY TOOK THE KEYBOARD AWAY!!! • ACORN WORLD 1996 • BLIND DEVOTION • FIVE YEARS AGO Autumn 1996 Issue 10 £0 WOW! 123> 10th ISSUE Index: Page 2 . Index. Page 3 . Editors Page. Page 4 . Point five decade. Page 5 . Databurst. Page 6 . The new ratings.. Page 7 . It’s time to kick some serious butt. Page 8 . Rendezvous. Page 9 . Diary of a demented hacker. Page 10 . Accents Page 11 . Tanks advertisement Page 12 . Qu’est-ce que c’est, ça? Page 14 . AW96 Attachment. Reader Survey Credits: Editor . Richard Murray. Contributors . Richard Murray, Acorn User (archives), Helen Rayner, John Stonier, Richard Sargeant (for ART WWW JPEGs), Dane Koekoek, the participant of the newsgroup “comp.sys.acorn.misc” and John Stonier. Graphics . Richard Murray and ART. You may print and/or distribute this document provided it is unaltered. The editor can be contacted by FidoNet netmail as “Richard Murray” at 2:254/86.1 or ‘[email protected]’. Feel free to comment or send submissions. Back issues, stylesheets, notes, logos and omitted articles are available from Encina BBS — netmail editor if you are interested. The contents of this magazine are © Richard Murray for legal reasons. Full credit is given to the individual authors of each article. All copyrights and/or trademarks used are acknowledged. All opinions stated are those of the article author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Frobnicate, BudgieSoft or Richard Murray. All reasonable care is taken in the production of this magazine, but we will not be legally liable for errors, or any loss arising from those errors. -

The WROCC 30.10 – January 2013

The Newsletter of the Wakefield RISC OS Computer Club For all users of the Acorn and RISC OS family of computers Volume 30 − No. 10 − January 2013 December’s Meeting Report CLUB UPDATE by Rick Sterry – [email protected] Once again, we devoted the December meeting the first question to the other teams (how to more frivolous activities, including the embarrassing), but fortunately this made no showing of some amusing images and videos. difference to the order of team scores. The Mince pies, Stollen, Genoa cake and shortbread runners-up were ‘The Wakers’ with a very biscuits were available for those who were not respectable 28 points, followed by ‘Hard too worried about the calorie count. Times’ with 22 points, ‘Amazement’ with 15 points, and bottom of the pile was ‘Vista The highlight of the evening was Peter Devils’ with a score of 13 – still not at all bad. Richmond’s fiendish computer-related quiz, There was no prize for the winning team, but with some relatively easy questions and a few hey, we’re British and it’s all about the taking really tough and/or obscure ones. We divided part. Those who couldn’t make it to the into five teams of three people each to answer meeting can also test their knowledge on the 30 questions, with a possible total score of quiz on the pages overleaf, but no cheating 34 points. The winning team with an please! impressive 33 points was ‘Clueless’, comprising Steve Fryatt, Dave Barrass and If you would like to find some of the images myself. -

Ravenskull-Alt

C(SUNRIOR ~ SOFIWARE ACORNS!FT Limited Compatible with the BBC B, B+ and Master Series computers Main Controls GAME CONTROLS -Run North Status Screen Controls ?• -Run South z - Move hand left (to select object) z -Run West x - Move hand right (to select object) x -Run East E - Examine object p - Pick up object J - Level jump (only available after completing !You c amol carry more than 3 objects of a limel the previous level without losing a life) RETURN -Use object w -Sound on D - Drop object Q -Sound off s - Select Status Screen A -Music on TAB - Kiii yourself s -Music off ESCAPE - Restart game 1' ~ - Sh ift screen up/down COPY -Freeze on SPACE BAR - Return to game DELETE -Freeze off Commodore GAME CHARACTERS Amstrad Sh ield Treasure Cryslalt:d log of Gold Man-fating Warrior Adventurer W izard Elf Chest Plant Ac id Pool BBC Micro Acorn Electron a ~ 'a U1l.... :--:- I & I] Disk Spikes Spiked Gate Wooden Cask Earth •Koy Plck·Axe Dynamite Detonator Scythe •Spade ~ " -.,._--:"'·-: ... ·1· jf The best is yet to come ... ~ . J iii --1 I Hand·AH Bow and Bell Com poss Mogle Scroll Ravenbee • Arrow Fish Cake Wine Mogle Potion • ' ........ ' ~ .,.. y ~ r .f. ;Q tit ~I II •111111111 1111 111 1THE ULTlnllTEr1•111 CHllLLEtlGE ~ 1 1111111 11111111• Released on November 5th for the BBC Micro, PRIZE COMPETITION The Prizes Acorn Electron, Commodore 64/128 and On 30th April 1987, a draw will be mode from all of the correct entries received. The winner of the draw Amstrad 464/664/6128 computers. -

Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529018f2 No online items Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Processed by Stephan Potchatek; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Special Collections M0997 1 Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: M0997 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Stephan Potchatek Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Date (inclusive): ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: Special Collections M0997 Creator: Cabrinety, Stephen M. Extent: 815.5 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Access restricted; this collection is stored off-site in commercial storage from which material is not routinely paged. Access to the collection will remain restricted until such time as the collection can be moved to Stanford-owned facilities. Any exemption from this rule requires the written permission of the Head of Special Collections. -

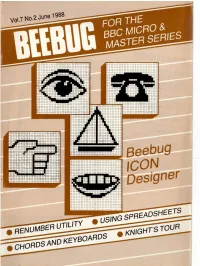

BEEBUG Vol.7 No.2

REVIEWS • S S S iff-6 12 SiDBeebDOSttomw— O StomM'c'°,10SS u 19 regular items 22 2 6 Editor’s Jottings 2 8 News '■ Supp'emert 3 0 Hints and Tips I M46 5Magazine* DiscfTapuiscm “ ^ ay* 1 50 HINTS & TIPS 53 54 (B W iS rt 60 Teletext Characters PROGRAM INFORMATION All programs listed in BEEBUG magazine are Programs are checked against all standard Acorn produced direct from working programs. They systems (model B, B+, Master, Compact and are listed in LIST01 format with a line length of 40. Electron; Basic I and Basic II; ADFS, DFS and However, you do not need to enter the space Cassette filing systems; and the Tube). We hope after the line number when typing in programs, as that the classification symbols for programs, and this is only included to aid readability. The line also reviews, will clarify matters with regard to length of 40 will help in checking programs listed compatibility. The complete set of icons is given on a 40 column screen. 1. Curve DrawingI 2. Knight's Tour 2- 3. Chords 4 Keyboards 4. Double View Review CHORD u"wf‘ K E V H O T E < n stvf' H Ritros»«lM 5 (con Designer X{}aJ 6. ADFS View Menu I Processor |ir*c*orV iursor Computer System Filing System below. These show clearly the valid combinations Master (Basic IV) ADFS 17* of machine (version of Basic) and filing system for Compact (Basic VI) DFS each item, and Tube compatibility. A single line through a symbol indicates partial working Model B (Basic II) Cassette U=] (normally just a few changes will be needed); a cross shows total incompatibility.