Hormonal Responses to Striking Combat Sports Competition: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time–Motion Analysis and Physiological Responses to Karate Official Combat Sessions: Is There a Difference Between Winners and Defeated Karatekas?

International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2014, 9, 302 -308 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.2012-0353 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. www.IJSPP-Journal.com ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Time–Motion Analysis and Physiological Responses to Karate Official Combat Sessions: Is There a Difference Between Winners and Defeated Karatekas? Helmi Chaabène, Emerson Franchini, Bianca Miarka, Mohamed Amin Selmi, Bessem Mkaouer, and Karim Chamari Purpose: The aim of this study was to measure and compare physiological and time–motion variables during karate fighting and to assess eventual differences between winners and defeated elite karatekas in an ecologi- cally valid environment. Methods: Fourteen elite male karatekas who regularly participated in national and international events took part in a national-level competition. Results: There were no significant differences between winners and defeated karatekas regarding all the studied variables. Karatekas used more upper-limb (76.19%) than lower-limb techniques (23.80%). The kisami-zuki represented the most frequent technique, with 29.1% of all used techniques. The duration of each fighting activity ranged from <1 s to 5 s, with 83.8% ± 12.0% of the actions lasting less than 2 s. Karatekas executed 17 ± 7 high-intensity actions per fight, which corresponded to ~6 high-intensity actions per min. Action-to-rest ratio was about 1:1.5, and high-intensity- action-to-rest ratio was ~1:10. The mean blood lactate response at 3 min postcombat (Lapost) elicited during karate fighting was 11.18 ± 2.21 mmol/L (difference between Lapre and Lapost = 10.01 ± 1.81 mmol/L). Mean heart rate (HR) was 177 ± 14 beats/min (91% ± 5% of HRpeak). -

Esport Karate-Do „Esport”Te-Do, Az Esport Kéz Útja

Esport Karate-Do „Esport”te-do, Az Esport kéz útja Moving towards Society 5.0 How can we move towards Society 5.0? The Hogyan léphetünk a Társadalom 5.0 felé? Egy obvious possible road to this super smart nyilvánvaló lehetséges út a szuper okos society leads through smart city, smart társadalom felé az okos városon, az okos education, smart health and so on... oktatáson, az okos egészségügyön s.t.b vezet... But we are convinced that the key link in this De meggyőződésünk, hogy ebben a process will be the individual, who will already folyamatban a legfontosabb láncszem az egyén grow up in the esport culture. lesz, aki már az esport kultúrájában fog felnőni. Esport culture is the pinnacle of Merlin Az esport-kultúra a Merlin Donaldi elméleti Donald's theoretical culture, where Artificial kultúra csúcsa, ahol a Mesterséges Általános General Intelligence (AGI) appears as an Intelligencia (AGI) újításként jelenik meg1, invention, like as before, when the theoretical csakúgy, mint korábban, amikor az elméleti culture was built on external memory and kultúra a külső memóriára és a vizuografikus visuographic invention. újításra épült. In the spirit of this we quote words of Shigeru Egami master, who was a student of Gichin Funakoshi, namely, Ennek szellemében idézzük Shigeru Egami mester szavait, aki Gichin Funakoshi tanítványa volt, nevezetesen: „First of all, we must practise Karate like a combat technique and then, with time and experience, we will be able to understand a certain state of soul and will be able to open ourselves to the horizons of 'jita-ittai' (the union of one with the other) which lay beyond fighting. -

Karate-Dō Shōtōkan - História, Princípios E Conceitos Básicos ______

José Erasmo de Oliveira Júnior 1 ___________________________________________________________ 2 Karate-Dō Shōtōkan - História, Princípios e Conceitos Básicos ___________________________________________________________ José Erasmo de Oliveira Júnior 3 ___________________________________________________________ KARATE-DŌ SHŌTŌKAN HISTÓRIA, PRINCÍPIOS E CONCEITOS BÁSICOS JOSÉ ERASMO DE OLIVEIRA JÚNIOR 4 Karate-Dō Shōtōkan - História, Princípios e Conceitos Básicos ___________________________________________________________ TODOS OS DIREITOS RESERVADOS Este trabalho é de propriedade intelectual de José Erasmo de Oliveira Júnior, não podendo ser comercializado sem a prévia autorização do autor, de acordo com a Lei 9.610 de 19 de fevereiro de 1998 (Lei dos Direitos Autorais). O autor autoriza a reprodução desta obra desde que sem fins comerciais, podendo ser copiada em sua integralidade e repassada com fins educacionais e sem ônus aos praticantes de Karate-Dō. de Oliveira Júnior, José Erasmo Karate-Dō Shotokan – História, Princípios e Conceitos Básicos - Brasília/DF, 2011. Revisado em 2016. 227 p. :il. _____________________________________________________________ José Erasmo de Oliveira Júnior 5 ___________________________________________________________ ÍNDICE INTRODUÇÃO........................................................................................07 BUNBU-ICHI [文武一]...........................................................................09 A ORIGEM DO KARATE-DŌ [空手道].................................................12 HISTÓRIA DO -

Coordinative Intra-Segment Indicators of Karate Performance

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Coordinative intra-segment indicators of karate performance Authors’ Contribution: Márcio Fagundes Goethel1ABCD, Ulysses Fernandes Ervilha1BCD, Pedro Vieira A Study Design 2BD 1D 2AD B Data Collection Sarmet Moreira , Venicius de Paula Silva , Antonio Roberto Bendillati , C Statistical Analysis Adalgiso Coscrato Cardozo2ABE, Mauro Gonçalves2ABE D Manuscript Preparation E Funds Collection 1 Sensory-Motor Interactions Research Group, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil 2 Department of Physical Education, São Paulo State University, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil Received: 27 June 2019; Accepted: 30 July 2019; Published online: 23 August 2019 AoBID: 12922 Abstract Background and Study Aim: Whether from the lower or upper limbs, intersegmental coordination is required at a high level in the blows of various martial arts modalities, with karate being no exception. In karate, precision, high speed, and tech- nique are the hallmarks of attack, counterattack, and defence. The aim of this study was the phase relation- ship between the proximal and distal joints during the execution of two technique of stroke karate: the punch gyaku tsuki and the kick mae geri. Material and Methods: The study included 14 male athletes, equally divided into 2 subgroups according to their current competi- tive level: sub-elite (SEG) and elite (EG). The karate stroke performance measure used was the linear veloci- ty peak of the wrist and foot. In order to analyze the intra-segment coordination, it was applied the nonlinear dynamics approach named continuous relative phase (CRP). From the CRP curve it was obtained the peak as well as the time to reach the CRP peak. It was also compared the index of the coordinative patterns’ variabil- ity, which was obtained by calculating the average of the CRP values and standard deviation. -

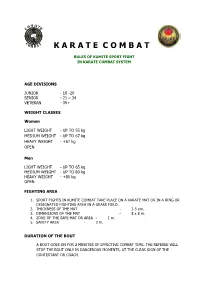

K a R a T E C O M B

K A R A T E C O M B A T RULES OF KUMITE SPORT FIGHT IN KARATE COMBAT SYSTEM AGE DIVISIONS JUNIOR - 18 -20 SENIOR - 21 – 34 VETERAN - 35+ WEIGHT CLASSES Women LIGHT WEIGHT - UP TO 55 kg MEDIUM WEIGHT - UP TO 67 kg HEAVY WEIGHT - +67 kg OPEN Men LIGHT WEIGHT - UP TO 65 kg MEDIUM WEIGHT - UP TO 80 kg HEAVY WEIGHT - +80 kg OPEN FIGHTING AREA 1. SPORT FIGHTS IN KUMITE COMBAT TAKE PLACE ON A KARATE MAT OR IN A RING OR DESIGNATED FIGHTING AREA IN A GRASS FIELD. 2. THICKNESS OF THE MAT - 2-5 cm. 3. DIMENSIONS OF THE MAT - 8 x 8 m. 4. ZONE OF THE SAFE MAT OR AREA - 1 m. 5. SAFETY AREA - 3 m. DURATION OF THE BOUT A BOUT GOES ON FOR 2 MINUTES OF EFFECTIVE COMBAT TIME. THE REFEREE WILL STOP THE BOUT ONLY IN DANGEROUS MOMENTS, AT THE CLEAR SIGN OF THE CONTESTANT OR COACH. CONTESTANTS’ CLOTHING CONTESTANTS PARTICIPATING IN KUMITE COMBAT SPORT FIGHTS SHALL WEAR: - white KARATE – GI - CONTESTANTS FIGHT BAREFOOT MANDATORY EQUIPMENT USED IN KARATE COMBAT SPORT FIGHTS in the Kumite Combat event - MMA GLOVES - (boxing) HEADGUARD - MOUTHPIECE - GROIN PROTECTOR - CHEST PROTECTOR FOR WOMEN - SHIN AND FOOT PROTECTOR (as in kumite sanbon shobu WUKF) PERMITTED EQUIPMENT USED IN KARATE COMBAT SPORT FIGHTS - HAND WRAPPING EQUIPMENT PROHIBITTED IN KARATE COMBAT SPORT FIGHTS - SPECTACLES - ADDITIONAL CLOTHING ELEMENTS JUDGES SPORT FIGHTS IN KUMITE COMBAT ARE EVALUATED BY: I. SUSHIN - THE CENTRAL REFEREE who conducts the bout on the mat II. FUKUSHIN - 3 SCORING JUDGES WHO SIT AT THE MAT ON CHAIRS, ON THE SIDES OF THE MAT III. -

Hur Shōtōkan-Karaten Kom Till Sverige Via Karateklubb Zendōkai

1 Hur Shōtōkan-karaten kom till Sverige via Karateklubb Zendōkai Av Roy Andersson, grundare av Karateklubb Zendōkai Min tid med Karateklubb Zendōkai Förord I följande text nämner jag den japanska titeln sensei bara när namnet presenteras första gången, an- nars blir det för tjatigt. För att underlätta uttalet anger jag lång vokal med ett streck ovanför, vilket framgår av ovanstående rubrik. Jag skriver japanska ord och uttryck med kursiv, med undantag för sådana ord som är helt ac- cepterade i svenska språket, t.ex. karate och budo. I mina skriverier låter jag alltid humor och självironi lysa igenom. Innehållsförteckning Hur Shōtōkan-karaten kom till Sverige via Karateklubb Zendōkai ......................................................... 1 Min tid med Karateklubb Zendōkai ..................................................................................................... 1 Förord .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Hur mitt eget intresse för budo började. ........................................................................................ 4 Halmstads första budo-klubb .......................................................................................................... 4 Första kontakten med karate .......................................................................................................... 4 Judo-träning i Stockholm ................................................................................................................ -

C.G. 2016 | 2017 C.G

1 ® 2016-17 C.G. 2016 | 2017 C.G. 2016 | 2017 2 UNIFORMI KARATE 5 JUDO 26 JUJITSU 36 BRAZILIAN JUJITSU 40 TAEKWONDO 42 AIKIDO 47 KUNG FU- TAI CHI 48 YOSEIKAN BUDO 49 KENDO 50 KRAV MAGA - DIFESA PERSONALE 51 CINTUREE 52 RICAMI 54 EMBLEMI - GADGET 58 PROTEZIONI GUANTINI 62 3 PARATIBIA - PARABRACCIO 64 CORPETTI 68 CASCHI 72 TAEKWONDO 75 CONCHIGLIE 77 PARADENTI E ACCESSORI 78 ARMI E ATTREZZIZI 82 DIPLOMI 95 SCUDI E COLPITORI 97 ACCESSORI ALLENAMENTO 103 TATAMI - YOGA 112 BORSE - ZAINI - SCARPE 115 ABBIGLIAMENTO SPORTIVO 120 C.G. 2016 | 2017 C.G. 2016 | 2017 4 karate 5 C.G. 2016 | 2017 42 kabuki TRaining IT Karategi per i campioni del futuro. Il tessuto leggero assicura anche per i più piccoli facilità di movimento e comfort. Nella confezione è com- presa la cintura bianca. Il pantalone è con elasti- co in vita e cordoncino interno. Articolo ideale per chi si avvicina per la prima volta alla pratica delle arti marziali. EN Karategi for next generation champions. The lightweight fabric assures even for youngers ease of movement and comfort. The package includes a white belt. Trousers with elastic band on waist and cordon inside. Product desiged for those who approach for the fi rst time the martial arts. KARATE 6 Dettaglio - Detail COD. PRODOTTO COLORE MISURA TESSUTO GRAMMATURA TAGLIO CINTURA code product color size fabric weight style belt 42 TRAINING Bianco 000-00-0-1-2-3 100% Cotone 200 gr./m² Tradizionale Cintura bianca inclusa White Cotton 100% Traditional White belt included 45N BABY Bianco 00000 (1-2 anni) 100% Cotone 200 gr./m² Tradizionale Cintura nera inclusa White 0000 (2-3 anni) Cotton 100% Traditional Black belt included C.G. -

Name Date Joined Martial Arts Style Gender Country Grade

Name Date Joined Martial Arts Style Gender Country Grade Abdul Basir Amarkhail 18/05/2015 2:48 Kyokushin Male Afghanistan 2nd Dan Dazi Zahir 12/08/2013 11:23 Karate Kick Boxing Male Algeria 6th Dan Dr.Allaoua Mohamed Rabie 6/05/2012 6:57 Shidokan Karatã© / Kick Boxing Male Algeria 2nd Dan Raul Edgardo Soria 2/01/2013 2:46 Karate Seishinkaikan Male Argentina 7th Dan Edik Sargsyan 23/04/2011 13:38 Kyokushinkai Karate Male Armenia 3rd Dan Edward Emin 7/10/2007 11:33 Kyokushin Kaikin Male Australia 8th Dan Kevin Blundell 5/11/2013 3:51 Kumiai-Ryu Martial Arts System Male Australia 8th Dan Peter Mcinnes 20/01/2014 1:44 Freestyle Karate Male Australia 8th Dan Si Fu Gawain Siu 12/10/2007 12:14 Ging Mo Kune (Kung Fu) Male Australia 7th Dan Terry Lim 9/02/2015 3:30 Loong Fu Pai Male Australia 7th Dan Guido Grima 19/05/2015 2:59 Willow Heart Yoshin Ryu Male Australia 7th Dan Barry Johnston 30/09/2007 12:42 Te Shin Kai Karate Male Australia 6th Dan Ross Cameron 15/07/2011 11:30 Hsou Jing Do Male Australia 6th Dan George Kolovos 13/09/2013 8:38 Kyokushin Male Australia 6th Dan Frank Monea 7/04/2015 5:05 Ryukyu Kempo Tomarite Male Australia 6th Dan Alex Kastamonitis 21/10/2009 7:45 Yoshin Martial Arts Male Australia 5th Dan Mark Cousins 6/02/2010 5:05 Ashihara Karate Male Australia 5th Dan Matt Mcgregor 22/03/2011 10:49 Kyokushin Karate Male Australia 5th Dan Stavros Saristavros 12/02/2013 22:26 Go Ju Karate, Kickboxing, Philippino, Bjj, Male Australia 5th Dan Freestyle Herve Vengatasamy 22/04/2013 4:45 Shorin Kempo Male Australia 5th Dan Susan Mclaughlin -

Revista ODEP, Indizada En

CUERPO DIRECTIVO COMITÉ EDITORIAL Director Mg. Adriana Angarita Fonseca Juan Luis Carter Beltrán Universidad de Santander, Colombia Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile Lic. Marcelo Bittencourt Jardim Editor CENSUPEG y CMRPD, Brasil Juan Guillermo Estay Sepúlveda Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile Mg. Yamileth Chacón Araya Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Secretario Ejecutivo y Enlace Investigativo Héctor Garate Wamparo Dr. Óscar Chiva Bartoll Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile Universidad Jaume I de Castellón, España Cuerpo Asistente Dr. Miguel Ángel Delgado Noguera Universidad de Granada, España Traductora: Inglés – Francés Pauline Corthorn Escudero Dr. Jesús Gil Gómez Asesorías 221 B, Chile Universidad Jaume I de Castellón, España Traductora: Portugués Ph. D. José Moncada Jiménez Elaine Cristina Pereira Menegón Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Asesorías 221 B, Chile Mg. Ausel Rivera Villafuerte Diagramación / Documentación Secretaría de Educación Pública SEP, México Carolina Cabezas Cáceres Asesorías 221 B, Chile Mg. Jorge Saravi Universidad Nacional La Plata, Argentina Portada Felipe Maximiliano Estay Guerrero Asesorías 221 B, Chile Comité Científico Internacional Ph. D. Víctor Arufe Giraldez Universidad de La Coruña, España Ph. D. Juan Ramón Barbany Cairo Universidad de Barcelona, España Ph. D. Daniel Berdejo-Del-Fresno England Futsal National Team, Reino Unido The International Futsal Academy, Reino Unido Dr. Antonio Bettine de Almeida Universidad de Sao Paulo, Brasil Dr. Oswaldo Ceballos Gurrola Dr. Osvaldo Javier Martín Agüero Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México Universidad de Camagüey, Cuba Ph. D. Paulo Coêlho Mg. Leonardo Panucia Villafañe Universidad de Coimbra, Portugal Universidad de Oriente, Cuba Editor Revista Arranca Dr. Paul De Knop Rector Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Bélgica Ph. -

Compare the Values of Blood Lactate and Heart Rate of Kickboxers During Kickboxing Matches

Journal of Education and Training Studies Vol. 5, No. 7; July 2017 ISSN 2324-805X E-ISSN 2324-8068 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://jets.redfame.com Compare the Values of Blood Lactate and Heart Rate of Kickboxers during Kickboxing Matches Mustafa Karadağ Correspondence: Mustafa Karadağ, Firat University, Faculty of Sports Science, 23119, Elazig, Turkey. Received: April 4, 2017 Accepted: May 25, 2017 Online Published: June 1, 2017 doi:10.11114/jets.v5i7.2317 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v5i7.2317 Abstract The aim of this study was to compare the values of heart rate (HR) and blood lactate (BL) of kickboxers during kickboxing match. This study was conducted with the participation of 18 male and 16 female sportsman in Turkish Kickboxing championship, an organization of Turkish Kickboxing Federation. After the participant athletes read and signed informed voluntary consent form (BGOF) prepared for them, the measurements were collected. While no significant difference was found between ages, pre-match HR, post-match HR, pre and post-match BL of male and female Kickboxers, a significant difference was statistically found between the height (P˂0.05) and body weights (P˂0.01) of athletes. Age distribution of athletes was determined as 14-23 and mean age distribution was determined as 17.03±2.41. HR pressures of athletes differs according to pre-match and post-match periods (P˂0.001). As HR frequencies increase by 29.4% according to pre-match HR regardless of the gender, this increase was determined as 31.4% for male athletes and 27.2% for female athletes. -

Distribution Prohibited This

© Idōkan Poland Association “IDO MOVEMENT FOR CULTURE. Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology”, Vol. 14, no. 3 (2014), pp. 10–21 DOI: 10.14589/ido.14.3.2 PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF MARTIAL ARTS AND COACHING The Author has been practising karate (shotokan, kyokushin and others) since 1980. He holds 8 consecutive kyu ranks in kyokushinkai and was an instructor of this style. From February 1993 he has been practising karate idokan (zendo karate tai-te-tao), as uchideshi of GM Lothar Sieber. He was a runner-up in the kata competition at the tournament of the IMAF Tokyo 2000. He received 4 dan in nihonden karate and kobudo, and 7 dan in idokan karate. He actively participates in the circle of Polish and European karate as a leader of the IPA and IMACSSS. Wojciech J. Cynarski Chair of Cultural Foundations for Physical Education, Tourism and Recreation, Faculty of Physical Education, University of Rzeszów, Rzeszów (Poland) e-mail: [email protected] The European karate today: The opinion of experts Submission: 12.10.2013; acceptance: 18.05.2014 Key words: martial art, sport, European karate, aims, changes, sportification Abstract: Aim. From the perspective of the “humanistic theory of martial arts” [Cynarski 2004, 2006a] and the “general theory of fighting arts” [Cynarski, Sieber 2012] the author tackles the problem of the main directions of changes and institutional development of karate in Europe. He puts forward a hypothesis that sportification is not a dominant direction of changes in karate. Method. Three complementary test methods for qualitative analysis were used: an analysis of subject matter literature; long-term participatory observation and the method of competent judges / expert courts. -

Aging Effects on Neuromuscular Activity in Karate Practitioners

Journal of Sports Science 3 (2015) 203-213 D doi: 10.17265/2332-7839/2015.05.001 DAVID PUBLISHING Aging Effects on Neuromuscular Activity in Karate Practitioners António Manuel Vitória Vences de Brito1,2,3, Mário André Ferreira Rodrigues1,2, Wojciech Jan Cynarski3,4, Carlos Gutiérrez García3,5 1. Sport Sciences School of Rio Maior, Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, 2040-413 Rio Maior, Portugal 2. Life Quality Research Centre-CIEQV, Complexo Andaluz, Apartado 279, 2001-904 Santarém, Portugal 3. International Martial Arts and Combat Sports Scientific Society—IMACSSS, 35-959 Rzeszow, A. Towarnickiego Str. 3/17A, Poland 4. Faculty of Physical Education, University of Rzeszów, Rzeszow 35-959, Poland 5. Department of Physical and Sport Education, Faculty of Physical and Sport Sciences, University of León, Vegazana Campus, 24071–León, Spain Abstract: Aging leads to a general decline in body functions that affects quality of life. Sports practice is recommended as a means to attenuate the impact of the aging process. The aim of this study was to identify and analyze the neuromuscular activity and its patterns on active karate practitioners and assess the effects of the aging process. Two groups of black belt male karate practitioners, one with nine practitioners over 50 years old and the other with 21 practitioners aged between 20-30 years old performed the frontal kick mae-geri. Kinematic and electromyographic data of five muscles were collected from the right leg. Results showed two distinct periods of muscular activation in the mae-geri performance, with similar muscles activity patterns between groups. Nevertheless, some differences were found in the muscles’ activity onset and offset, in root mean square and in inter-muscle delay and co-contraction periods.