Distribution Prohibited This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Karate Federation

World Karate Federation Kata Competition Examination questions for Kata Judges Version January 2019 The answer paper is to be returned to the examiners. All answers are to be entered on the separate answer paper only. You must make sure that your name, country, number and any other information required are entered on the answer paper. You may not have any additional papers or books on your desk while undertaking this examination. During the examination to be seen speaking to another candidate or copying another’s paper will mean suspension and automatic failure of the examination. If you are not sure of the correct procedures or have any questions about any aspect of the examination you should speak only to an examiner. The result of the examination both theory and practical will be sent to the candidate’s National Federation. January 2019 Kata Examination Paper. Version January 2019 1 / 6 World Karate Federation KATA EXAMINATION “TRUE OR FALSE” On the answer paper put an “X” in the appropriate box. The answer to a question is true only if it can be held to be true in all situations; otherwise it is considered to be false. Each correct answer scores one point. 1. Competitors must wear a plain blue or red belt corresponding to their pool. 2. The total time allowed for the Kata and Bunkai demonstration combined, is six minutes. 3. In Kata competition slight variations as taught by the contestant's style (Ryu-ha) are permitted. 4. Glasses are forbidden in kata completion. 5. The number of Competitors will determine the number of groups to facilitate the elimination rounds. -

April 2007 Newsletter

December 2018 Newsletter Goju-Ryu Karate-Do Kyokai www.goju.com ________________________________________________________ Obituary: Zachary T. Shepherdson-Barrington Zachary T. Shepherdson-Barrington 25, of Springfield, passed away at 1:22 p.m. on Tuesday, November 27, 2018 at Memorial Medical Center. Zachary was born October 12, 1993 in Springfield, the son of Kim D. Barrington and Rebecca E. Shepherdson. Zachary attended Lincoln Land Community College. He was a former member of The Springfield Goju-Ryu Karate Club where he earned a brown belt in karate. He worked for Target and had worked in retail for several years. He also worked as a driver for Uber. He enjoyed game night with his friends and working on the computer. He was preceded in death by his paternal grandparents, James and Fern Gilbert; maternal grandparents, Carol J. Karlovsky and Harold T. Shepherdson; seven uncles, including Mark Shepherdson; and aunt, Carolyn Norbutt. He is survived by his father Kim D. Barrington (wife, Patricia M. Ballweg); mother, Rebecca E. Shepherdson of Springfield; half-brother, Derek Embree of Girard; and several aunts, uncles, and cousins. Cremation will be accorded by Butler Cremation Tribute Center prior to ceremonies . Memorial Gathering: Family will receive friends from 10:00 to 10:45 a.m. on Tuesday, December 4, 2018 at First Church of the Nazarene, 5200 S. 6th St., Springfield. Memorial Ceremony: 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, December 4, 2018 at First Church of the Nazarene, with Pastor Fred Prince and Pastor Jay Bush officiating. Memorial contributions may be made to the American Cancer Society, 675 E. Linton, Springfield, IL 62703. -

Time–Motion Analysis and Physiological Responses to Karate Official Combat Sessions: Is There a Difference Between Winners and Defeated Karatekas?

International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2014, 9, 302 -308 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/IJSPP.2012-0353 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. www.IJSPP-Journal.com ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Time–Motion Analysis and Physiological Responses to Karate Official Combat Sessions: Is There a Difference Between Winners and Defeated Karatekas? Helmi Chaabène, Emerson Franchini, Bianca Miarka, Mohamed Amin Selmi, Bessem Mkaouer, and Karim Chamari Purpose: The aim of this study was to measure and compare physiological and time–motion variables during karate fighting and to assess eventual differences between winners and defeated elite karatekas in an ecologi- cally valid environment. Methods: Fourteen elite male karatekas who regularly participated in national and international events took part in a national-level competition. Results: There were no significant differences between winners and defeated karatekas regarding all the studied variables. Karatekas used more upper-limb (76.19%) than lower-limb techniques (23.80%). The kisami-zuki represented the most frequent technique, with 29.1% of all used techniques. The duration of each fighting activity ranged from <1 s to 5 s, with 83.8% ± 12.0% of the actions lasting less than 2 s. Karatekas executed 17 ± 7 high-intensity actions per fight, which corresponded to ~6 high-intensity actions per min. Action-to-rest ratio was about 1:1.5, and high-intensity- action-to-rest ratio was ~1:10. The mean blood lactate response at 3 min postcombat (Lapost) elicited during karate fighting was 11.18 ± 2.21 mmol/L (difference between Lapre and Lapost = 10.01 ± 1.81 mmol/L). Mean heart rate (HR) was 177 ± 14 beats/min (91% ± 5% of HRpeak). -

Seiunchin Kata Bunkai

Seiunchin Kata Bunkai Bunkai Description Kata Description Rei (bow) Rei (bow) Set (salutation) Set (salutation) Heiko dachi (parallel stance, ready position) Heiko dachi (parallel stance, ready position) 1. Look to left, slide right foot straight ahead into Move to opponent's left; grab high. Seiunchin dachi, hands posted at ready. Bring open hands up and out (breaking grab), execute double low From opponent diagonal, right blocks to sides (kick coming from 45º). Right hand straightforward kick. Right step and punch. middle haito block, grab and pull into left hand nukite. 2. Look over right shoulder, slide left foot toward front. Move to opponent right; grab high. Bring open hands up and out (breaking grab), execute double low blocks to sides. Left hand middle haito From opponent diagonal, left block, grab and pull into right hand nukite. straightforward kick. Left step and punch. 3. Look behind over left shoulder, slide right foot Move to opponent left; grab high. toward front. Bring open hands up and out (breaking grab), execute double low blocks to sides. Right hand From opponent diagonal, right middle haito block, grab and pull into left hand nukite. straightforward kick. Right step and punch. 4. Catch kick (punch) with left hand with right hand back Move to opponent front. Right fist leg while sliding left foot back into cat stance. Put straightforward kick, land right foot left hand shuto on top of right wrist in reinforcing forward. position (also kamae). 5. Slide forward with right foot into Seisan dachi, right hand reinforced punch to solar plexus. Grab behind Be punched, struck with upward elbow opponent's head with left hand, right elbow strike up strike. -

SHOTOKAN KARATE Grading Requirements White to 1St Degree Black Belt

SHOTOKAN KARATE Grading Requirements White to 1st degree Black Belt 9th Kyu 8th Kyu 7th Kyu 6th Kyu 5th Kyu 4th Kyu 3rd Kyu 2nd Kyu 1st Kyu SHODAN KIHON yellow orange Red Green Purple Blue Brown Brown Brown Black Belt Stances: Front, Back, Horse, Attention, Ready X X Kizame zuki and Gyaku-zuki X X X X X Knowledge Oi-zuki and Sambn zuki Test (ask) Gedan-bari and Age-uke Can recite Student Creed and Dojo Kun confidently Soto-uke and Uchi-uke Shuto-uke Dojo Etiquette Mae-geri Mawashi-geri Yoko-geri ke-age/Kekome Ushiro-geri OR Ushiro mawashi-geri Basic Blocks + Gyakuzuki and Nukite Oi-zuki > Gyaku-zuki Soto-uke > enpi > uraken > g.zuki Spinning Uraken > Gyaku-zuki Jab > reverse punch freestyle On the spot & slide-slide Kekome from zenkutsu-dachi > Gyakuzuki Rengeri: 2 X Yoko geri / Mae + Mawashigeri Special content of the term ??? ask and find out what it is ahead of time, if not sure what it is ? ? ? KickBox Combos: 1,2,3,4 Control/Precision/Impact KATA Heian Shodan Choice of 1 Kihon Kata Choice of 1 Advanced Kata One Tokui Kata and Remember: for Black belt exam you may be asked to (unless other kata recommended by sensei) (unless other kata recommended Bunkai of it perform any of the Kihon Katas by sensei) Bassai,dai Kankudai, Jion or Empi +One Kihon-Kata chosen by examiner KUMITE / APPLICATIONS Gohon Kumite Kihon Ippon Kumite Choice of: n/a Jodan and Chudan Oi-zuki Jodan and Chudan Oi-zuki, Chudan mae-geri, Jyu ippon kumite Blocks; Age-uke and Soto uke Mawashi-geri, Kekome Or. -

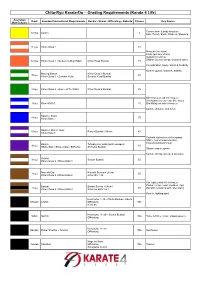

Chito-Ryu Karate-Do – Grading Requirements (Karate 4 Life)

Chito-Ryu Karate-Do – Grading Requirements (Karate 4 Life) Australian Rank Standard International Requirements Bunkai ▪ Ukemi ▪ Officiating ▪ Kobudo Fitness Key Basics Belt Colours Correct form & body structure 12 kyu Basics 5 Kick, Punch, Block, Stances, Stepping 11 kyu Kihon Dosa 1 10 Metsuke (eye focus) Hikite (pull back of arm) Seiken (correct fist) Shibori (squeeze armpit, shoulders down) 10 kyu Kihon Dosa 2 ▪ Seiken no Migi Hidari Kihon Dosa Bunkai 15 Co-ordination, body control & flexibility Kumite: guard, footwork, attacks Moving Basics Kihon Dosa 3 Bunkai 9 kyu 20 Kihon Dosa 3 ▪ Zenshin Kotai Zenshin Kotai Bunkai 8 kyu Kihon Dosa 4 ▪ Enpi ▪ 27 Te Waza Kihon Dosa 4 Bunkai 25 Kime (focus at end of technique) Seichusen (correct centre line, target) 7 kyu Kihon Kata 1 30 Breathing (out with techniques) Kumite: distance & defence Basics ▪ Kicks 6 kyu 35 Kihon Kata 2 Basics ▪ Rinten Tsuki 5 kyu Rinten Bunkai ▪ Ukemi 40 Kihon Kata 3 Suriashi (sliding feet while stepping) Shime (correct muscle tension) Hikiashi (pull back of leg) Basics Tehodoki no waza (wrist escapes) 4 kyu 45 Shiho Wari ▪ Shime Kata ▪ Shihohai Shihohai Bunkai Sharpening weapons Kumite: timing, speed & accuracy Seisan 3 kyu Seisan Bunkai 50 Kihon Dosa 2 ▪ Kihon Kata 1 Niseishi Dai Niseishi Bunkai ▪ Ukemi 2 kyu 55 Kihon Dosa 3 ▪ Kihon Kata 2 Kihon Bo 1-14 Kiai (spirit united with technique) Posture (align - head, shoulders, hips) Bassai Bassai Bunkai ▪ Ukemi 1 kyu 60 Zanshin (remaining spirit, after attack) Kihon Dosa 4 ▪ Kihon Kata 3 Kihon bo kata 1 & 2 Kumite: fighting spirit Henshuho 1~10 ▪ Chinto Bunkai ▪ Ukemi Shodan Chinto Officiating 100~ Kumi bo Henshuho 11~20 ▪ Sochin Bunkai Nidan Sochin 100~ Tame & Kime (elastic, whipping power) Officiating Henshuho 21~28 Sandan Rohai Sho/Dai ▪ Tenshin 100~ Seichusen Officiating Nage no Kata Yondan Sanshiru Officiating 100~ Tanden Sakugawa no kon. -

Esport Karate-Do „Esport”Te-Do, Az Esport Kéz Útja

Esport Karate-Do „Esport”te-do, Az Esport kéz útja Moving towards Society 5.0 How can we move towards Society 5.0? The Hogyan léphetünk a Társadalom 5.0 felé? Egy obvious possible road to this super smart nyilvánvaló lehetséges út a szuper okos society leads through smart city, smart társadalom felé az okos városon, az okos education, smart health and so on... oktatáson, az okos egészségügyön s.t.b vezet... But we are convinced that the key link in this De meggyőződésünk, hogy ebben a process will be the individual, who will already folyamatban a legfontosabb láncszem az egyén grow up in the esport culture. lesz, aki már az esport kultúrájában fog felnőni. Esport culture is the pinnacle of Merlin Az esport-kultúra a Merlin Donaldi elméleti Donald's theoretical culture, where Artificial kultúra csúcsa, ahol a Mesterséges Általános General Intelligence (AGI) appears as an Intelligencia (AGI) újításként jelenik meg1, invention, like as before, when the theoretical csakúgy, mint korábban, amikor az elméleti culture was built on external memory and kultúra a külső memóriára és a vizuografikus visuographic invention. újításra épült. In the spirit of this we quote words of Shigeru Egami master, who was a student of Gichin Funakoshi, namely, Ennek szellemében idézzük Shigeru Egami mester szavait, aki Gichin Funakoshi tanítványa volt, nevezetesen: „First of all, we must practise Karate like a combat technique and then, with time and experience, we will be able to understand a certain state of soul and will be able to open ourselves to the horizons of 'jita-ittai' (the union of one with the other) which lay beyond fighting. -

Zanshin Jan 2005.Pub

Volume 8 Issue 1 Newsletter of the Yoshukan Karate Association February 2005 Yoshukan Honbu Dojo Opened! Yoshukan Honbu Dojo Opened The Yoshukan Karate Association Honbu (Headquarters) Dojo opened in Mississauga, Ontario on January 1st, 2005. The dojo has 3,600 Sq. Ft. of floor space and houses: Main dojo floor (1,500 sq. ft.); second floor matted dojo; office; locker rooms; handicapped washroom; full kitchen; parent and stu- dent lounge; exercise area with universal gym; treadmill; stretching bar; library; washer/dryer units; and (under con- struction) massage/meditation room and sauna. The dojo project was lead by Sensei Betty Gormley and Gen- eral Contractor, Gordon Deane. The building is owned by Kancho Robertson and Sensei Gormley who took possession New Honbu Dojo main floor. A Kumite ring has been added in in August, 2004. Gord’s work crew (Spud; Matt; Keith; Jeff) red hardwood for members to practice their competition skills and the dojo volunteers (dozens!!) pitched in to make the space something we are all proud of. Special thanks to the dozens of dojo volunteers who devoted their XMAS-New Year’s break to get the dojo up and run- ning for our January 1st launch. Dojo members also generously donated the fridge; stove; dishwasher; microwave; coffee maker and kettle. Academy parents now get to have a coffee and read the paper while their kids train. The main dojo floor was constructed with special rubber ‘pucks’ (placed one foot apart) to give the floor a special ‘bounce’ while training. The locker rooms feature separate washrooms, showers, sinks, cubbies and (shortly) lockers. -

Okinawan Shorei-Kempo Karate

Okinawan Shorei-Kempo Karate Shawano Dojo Class Materials What is Karate? Karate is the ultimate of the unarmed martial arts. The word karate means empty hands: kara – empty, te – (pronounced “tay”) hands. Therefore empty hands, or hands without a weapon. Actually the hands, elbows, knees, feet and other parts of the body are the Karate-ka’s (person’s) weapons. Karate utilizes the many unique characteristics of the human anatomy to produce the most efficient and effective striking blows possible. Proper instruction will provide the karate-ka with kicking, punching, slashing, clawing, stabbing and gouging techniques, along with a few grappling and throwing techniques which are used in special instances where it is more practical to throw an opponent than to deliver a strike or blow. The superficial purpose of Shorei-Kempo Karate, as with any form of martial art, is that of self-defense, or learning to block, punch and kick. If self-defense were the sole motivator, however, simply purchasing a weapon of some sort would suffice. Choosing to go through all the work of learning karate would be unnecessary. The underlying purpose of Shorei-Kempo is the development of the art of self-control, based on the philosophy that in our life exists a union of body, mind and spirit (chi). As we learn to control the body, we learn to control the mind. The trained mind can then take over in times of stress, depression, anger and fear with poise and control. This is useful not only in self-defense, but in all aspects of daily life. -

2019 Kumite Esordienti M Risultati.Pdf

Lista ufficiale dei risultati / 2019-CAMPIONATO ITALIANO ESORDIENTI KUMITE M/F - 2019-11-16 Lista ufficiale dei risultati 2019-CAMPIONATO ITALIANO ESORDIENTI KUMITE M/F - 2019-11-16 ESORDIENTI M KUMITE 33-40 KG (Iscrizioni: 61 ) ESORDIENTI M KUMITE 33-40 KG (Iscrizioni: 61 ) Cl. Atleta Società P.ti 1 SQUILLANTE GUIDO 2006-08-22 ASSOCIAZIONE POLISPORTIVA 15SA1180 10 DILETTANTISTICA SHIRAI CLUB S.VALENTINO 2 GIORDANO FABRIZIO 2006-04-20 A.S.DILETTANTISTICA TALARICO KARATE 01TO3094 8 TEAM 3 DAVANZO ROBERTO 2006-09-26 POLISPORTIVA A.S.DILETTANTISTICA MASTER 19CT1711 6 CLUB MISTERBIANCO 3 PAPAGNI FEDERICO 2006-02-21 ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 16BA0331 6 KYOHAN SIMMI BARI 5 CIAVARELLA RICCARDO 2007-11-07 A.S.DILETTANTISTICA TALARICO KARATE 01TO3094 4 TEAM 5 ODELLO ANDREA 2007-02-05 ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 07SV1255 4 KARATE CLUB SAVONA 7 VANDINI ALESSANDRO 2007-07-05 ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 03MI1627 2 CINTURA NERA KARATE 7 DIGLIO MICHELE 2006-11-11 G.S.FIAMME ORO ROMA 12RM0061 2 7 TREVISAN DAVIDE 2006-09-13 ACADEMY PONTE DI PIAVE ASSOCIAZIONE 05TV0503 2 SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 7 GALATI GIUSEPPE 2006-02-01 A.S.DILETTANTISTICA DOJO KARATE-DO- 19PA0975 2 G.FUNAKOSHI 11 CELENTANO ANTONIO 2007-01-09 ASSOCIAZIONE POLISPORTIVA 15SA1180 1 DILETTANTISTICA SHIRAI CLUB S.VALENTINO 11 PAGANO LUIGI 2007-11-17 A.S.DILETTANTISTICA KARATE TEAM 15CE3074 1 CAPASSO GRUPPO SPORTIVO ASSOCIAZIONE NAZIONALE CARABINIERI 11 TOZZI MANUEL 2007-07-28 A.S.DILETTANTISTICA TOMARI-TE 12LT3595 1 11 DAIDONE FILIPPO 2007-01-26 A.DILETTANTISTICA -

Shotokan Datoer

SHOTOKAN RELATERTE VIKTIGE DATOER 1372- Det tidligste tidspunktet for nedtegnelser av kampkunst på Okinawa. 1390 tallet- 36 kinesiske familier med yrke som båtbyggere ankom Okinawa og introduserte Kinesisk kampkunst. 1429- Kong Sho Hashi (1372-1439) samler Okinawa til ett rike og forbyr krigerklassen å bære våpen. Ca 1500- Kong Sho Hashi konfiskerer alle våpen på Okinawa 1609- samuraier fra Satsuma klanen iverksetter en 40 dager lang kampanje mot Okinawa og iverksatte igjen forbud mot alle våpen. De nedla Kongens sverdsmie i Shuri og tok den ploitiske kontrollen på Øygruppen. Dette skjøt fart i kampkunstens utvikling. 1735- Sakugawa fra Akata som studerte Kinesisk boksing returnerte til Okinawa for å undervise. 1785- Shiodaira fra Shuri nedtegner et referat fra en oppvisning som skal ha funnet sted med den kinesiske militærattacheen Kushanku. Det finnes nedtegnelser som tyder på at Kushanku ikke er en person men en referanse til en militær grad. 1809- Sokon Matsumura blir født i Shuri. Kilder varierer veldig fra 1798 og oppover, men vestlige historikere regner denne datoen som mest korrekt av kildene. 1816- 19. oktober. Kaptein Basil Hall på HMS Lyra beskriver i boken sin ”Account of a voyage of discovery to the west coast of Cora and the great Looo-Choo island” en Shizoku som viste en uventet spesiell kampkunst. 1827/28- Yasutsune Azato blir født. Han begynner seinere å studere kampkunst under Sokon Matsumura. 1830/32- Yasutsune Itosu blir født. Han begynner seinere å studere kampkunst under Gusukuma fra Tomari. 1837- Den legendariske konkurransen mellom Matsumura og Uehara finner sted på Kinbu kirkegården. Funakoshi refererer til denne historien i 2 av sine bøker, og trekker den frem som det ultimate målet med karate; vinne over en fiende uten å slåss. -

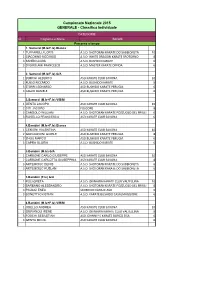

Classifica Di Società Nazionale 2015 GENERALE DEFINITIVA.Xlsx

Campionato Nazionale 2015 GENERALE - Classifica Individuale CATEGORIE Cl. Cognome e Nome Società Percorso a tempo 1. Samurai (M.le/F.le) Bianca 1 TUFFARELLI LORIS A.S.D. SHOTOKAN KARATE DO SABBIONETA 10 2 GIACCHINO RICCARDO A.S.D. WHITE DRAGON KARATE SPOTORNO 8 3 RANERI LAURA A.S.D. BUSHIDO KARATE 6 3DI GIROLAMI FRANCESCO A.S.D. MASTER KARATE OFFIDA 6 2. Samurai (M.le/F.le) G/A 1 BURCHI ALBERTO ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 10 2 RUSSO RICCARDO A.S.D. BUSHIDO KARATE 8 3 STORRI LEONARDO ASD BUSHIDO KARATE PERUGIA 6 3 GIGLIO DANIELE ASD BUSHIDO KARATE PERUGIA 6 3.Samurai (M.le+F.le) V/B/M 1 GENTA JACOPO ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 10 2 CITI JACOPO FOLGORE 8 3 CANDOLO WILLIAM A.S.D. SHOTOKAN KARATE POZZUOLO DEL FRIULI 6 3 ROSELLO FRANCESCA ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 6 4.Bambini (M.le+F.le) Bianca 1 CERIONI VALENTINA ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 10 2 GIOVAGNONI GIOELE ASD BUSHIDO KARATE PERUGIA 8 3 ZHOU MARCO ASD BUSHIDO KARATE PERUGIA 6 3 CAPRA GLORIA A.S.D. BUSHIDO KARATE 6 5.Bambini (M.le) G/A 1 CARBONE CARLO GIUSEPPE ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 10 2 CARBONE CARLOTTA GIUSEPPINA ASD KARATE CLUB SAVONA 8 3 ARTEMCIUC DENIS A.S.D. SHOTOKAN KARATE DO SABBIONETA 6 3 ARTEMCIUC RUSLAN A.S.D. SHOTOKAN KARATE DO SABBIONETA 6 5.Bambini (F.le) G/A 1 POLI GRETA A.S.D. OKINAWA KARATE CLUB VALTELLINA 10 2 BARBANO ALESSANDRO A.S.D. SHOTOKAN KARATE POZZUOLO DEL FRIULI 8 3 PAUCCI ENEA SKORPION KARATE ASD 6 3 BONETTI CRISTIAN A.S.D.