Disarmament and International Security Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peran Pemerintah Bangladesh Dalam Menangatasi Masalah Pekerja Anak Dalam Industri Fast Fashion Tahun 2009-2019

PERAN PEMERINTAH BANGLADESH DALAM MENANGATASI MASALAH PEKERJA ANAK DALAM INDUSTRI FAST FASHION TAHUN 2009-2019 SKRIPSI Diajukan Kepada Program Studi Hubungan Internasional Fakultas Psikologi dan Ilmu Sosial Budaya Universitas Islam Indonesia Untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Dari Syarat Guna Memperoleh Derajat Sarjana S1 Hubungan Internasional oleh: Rafi Pasha Hartadiputra 17323085 PROGRAM STUDI HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS PSIKOLOGI DAN ILMU SOSIAL BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA 2021 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN Skripsi dengan Judul: PERAN PEMERINTAH BANGLADESH DALAM MENGATASI MASALAH PEKERJA ANAK DALAM INDUSTRI FAST FASHION TAHUN 2009-2019 Dipertahankan di Depan Penguji Skripsi Prodi Hubungan Internasional Fakultas Psikologi dan Ilmu Sosial Budaya Universitas Islam Indonesia Untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Dari Syarat-Syarat Guna Memperoleh Derajat Sarjana S1 Hubungan Internasional Pada Tanggal: 7 April 2021 Mengesahkan Program Studi Hubungan Internasional Fakultas Psikologi dan Ilmu Sosial Budaya Universitas Islam Indonesia Ketua Program Studi (Hangga Fathana, S.I.P., B.Int.St., M.A) Dewan Penguji: TandaTangan 1. Hadza Min Fadhli Robby, S.IP., M.Sc. 2. Gustri Eni Putri, S.IP., M.A. 3. Hasbi Aswar, S.IP., M.A. HALAMAN PERNYATAAN Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini,saya : Nama : Rafi Pasha Hartadiputra No. Mahasiswa 17323085 Program Studi : Hubungan Internasional Judul Skripsi :Peran Pemerintah Bangladesh dalam Mengatasi Masalah Pekerja Anak dalam Industri Fast Fashion Tahun 2009- 2019 Melalui surat ini saya menyatakan bahwa : Selama melakukan penelitian dan -

Reference a State of Emergency in Anabout Coronavirus Disease

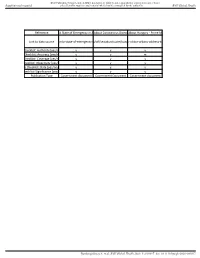

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Reference A State of Emergency in AnAbout Coronavirus DiseaseAbout Hungary - Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s address to the Hungarian parliament before the start of daily business [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 8]. Available from: http://abouthungary.hu/speeches-and-remarks/prime-minister-viktor-orbans-address-to-the-hungarian-parliament-before-the-start-of-daily-business/ Link to data sourcelease.com/a-state-of-emergency-ino.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/ister-viktor-orbans-address-to-the-h S Checklist: Authority [yes/no y y y S Checklist: Accuracy [yes/no/ y y m S Checklist: Coverage [yes/no/ y y y S Checklist: Objectivity [yes/no y y y CODS Checklist: Date [yes/no/m y y y S Checklist: Significance [yes/no y y y Publication Type Government document Government Document Government document Bandyopadhyay S, et al. BMJ Global Health 2021; 5:e003097. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003097 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Actualité [Internet]. [cited Another2 445 coronavirus casesattualita.it. Contagio CoronAustralian Government Depar w.sante.gov.ma/pages/actualites.asp8/another-445-coronavirus-cases-c a/contagio-coronavirus-aggio/resources/publications/coron y m y Y y y m Y y m y Y y y y Y y y y Y y y y Y Government Document Government Document Government Document Government Document Bandyopadhyay S, et al. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

How the Pandemic Should Provoke Systemic Change in the Global Humanitarian System

i COVID-19 and Humanitarian Access How the Pandemic Should Provoke Systemic Change in the Global Humanitarian System By Dr Rebecca Brubaker, Dr Adam Day, and Sophie Huvé Dr Rebecca Brubaker is Senior Policy Adviser, Dr Adam Day is Director of Programmes, and Sophie Huvé is Legal Expert at United Nations University Centre for Policy Research. 14 February 2021 This project was commissioned by the Permanent Mission of the United Kingdom to the United Nations. The views in this study do not necessarily represent the official views of the UK Government. This report benefited from insightful input from Smruti Patel, Aurelien Buffler, Hugo Slim, Sophie Solomon, Marta Cali, Omar Kurdi, Jacob Krutzer and a number of other individuals. All opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors’ alone. ISBN: 978-92-808-6530-1 © United Nations University, 2021. All content (text, visualizations, graphics), except where otherwise specified or attributed, is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). Using, re- posting and citing this content is allowed without prior permission. Citation: Rebecca Brubaker, Adam Day and Sophie Huvé, COVID-19 and Humanitarian Access: How the Pandemic Should Provoke Systemic Change in the Global Humanitarian System (New York: United Nations University, 2021) Cover photo: UN Photo/Martine Perret Contents I. Executive Summary �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 II. Pre-existing Access Challenges ......................................................................3 -

1 V.9 I.1 Cornell International Affairs Review Board of Advisors

1 V.9 I.1 CORNELL INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW BOARD OF ADVISORS Dr. Heike Michelsen, Primary Advisor Director of Programming, Einaudi Center for International Studies Professor Robert Andolina Cornell Johnson School of Management Professor Ross Brann Department of Near Eastern Studies Professor Matthew Evangelista Department of Government Professor Peter Katzenstein Department of Government Professor Isaac Kramnick Department of Government Professor David Lee Department of Applied Economics and Management Professor Elizabeth Sanders Department of Government Professor Nina Tannenwald Brown University Professor Nicolas van de Walle Department of Government Cornell International Affairs Review, an independent student organization located at Cornell University, produced and is responsible for the content of this publication. This publication was not reviewed or approved by, nor does it necessarily express or reflect the policies or opinions of, Cornell University or its designated representatives. 2 CIAR CORNELL INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW GRADUATE STUDENT SENIOR ADVISORS Wendy Leutert PhD Candidate Department of Government Whitney Taylor PhD Candidate Department of Christine Barker Masters Candidate Cornell Institute for Public Affairs 3 V.9 I.1 PRESIDENTS’ LETTER Lucas Png Cornell University Class of 2017 President, CIAR Thank you for picking up a copy of our latest issue. CIAR is grateful for your sup- port! Our club has grown with an influx of freshmen and new members, and at the end of this current year, we will be passing the torch to the next Executive Board, to continue CIAR’s mission of stimulating discussion about international affairs at Cornell and beyond. The Journal is as stunning as ever. By no means a quick read, it provides insight- ful and thought provoking analysis of important issues at hand. -

CPIN Template 2018

Country Policy and Information Note Cameroon: Anglophones Version 1.0 March 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia

Failed Decolonization of Africa and the Rise of New States: Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Roland Ngwatung Afungang* pp. 53-75 Introduction From the 1870s to the 1900s, many European countries invaded Africa and colonized almost the entire continent except Liberia and Ethiopia. African kingdoms at the time fought deadly battles with the imperialists but failed to stop them. The invaders went on and occupied Africa, an occupation that lasted up to the 1980s. After World War II, the United Nations (UN) resolution 1514 of 14 December 1960 (UN Resolution 1415 (1960), accessed on 13 Feb. 2019) obliged the colonial powers to grant independence to colonized peoples and between 1957 and 1970, over 90 percent of African countries got independence. However, decolonization was not complete as some colonial powers refused to adhere to all the provisions of the above UN resolution. For example, the Portuguese refused to grant independence to its African colonies (e.g. Angola and Mozambique). The French on their part granted conditional independence to their colonies by maintaining significant ties and control through the France-Afrique accord (an agreement signed between France and its colonies in Africa). The France-Afrique accord led to the creation of the Franc CFA, a currency produced and managed by the French treasury and used by fourteen African countries (African Business, 2012). CFA is the acronym for “Communauté Financière Africaine” which in English stands for “African Financial Community”. Other colonial powers violated the resolution by granting independence to their colonies under a merger agreement. This was the case of former British Southern Cameroons and Republic of Cameroon, South Sudan and Republic of Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Senegal and Gambia (Senegambia Confederation, 1982-1989). -

The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon

The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon This book provides a systematic analysis of the major structural and institutional governance mechanisms in Cameroon, critically analysing the constitutional and legislative texts on Cameroon’s semi-presidential system, the electoral system, the legislature, the judiciary, the Constitutional Council and the National Commission on Human Rights and Freedoms. The author offers an assessment of the practical application of the laws regulating constitutional institutions and how they impact on governance. To lay the groundwork for the analysis, the book examines the historical, constitutional and political context of governance in Cameroon, from independence and reunification in 1960–1961, through the adoption of the 1996 Constitution, to more recent events including the current Anglophone crisis. Offering novel insights on new institutions such as the Senate and the Constitutional Council and their contribution to the democratic advancement of Cameroon, the book also provides the first critical assessment of the legislative provisions carving out a special autonomy status for the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and considers how far these provisions go to resolve the Anglophone Problem. This book will be of interest to scholars of public law, legal history and African politics. Laura-Stella E. Enonchong is a Senior Lecturer at De Montfort University, UK. Routledge Studies on Law in Africa Series Editor: Makau W. Mutua The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon Laura-Stella E. Enonchong The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon Laura-Stella E. Enonchong First published 2021 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 Laura-Stella E. -

CPIN Template 2018

Country Policy and Information Note Cameroon: North-West/South-West crisis Version 2.0 December 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive)/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

CAMEROUN La Crise Anglophone : Situation Sécuritaire

COMMISSARIAT GÉNÉRAL AUX RÉFUGIÉS ET AUX APATRIDES COI Focus CAMEROUN La crise anglophone : situation sécuritaire 1er octobre 2019 (mise à jour) Cedoca Langue de l’original : français DISCLAIMER: Ce document COI a été rédigé par le Centre de documentation et de This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and recherches (Cedoca) du CGRA en vue de fournir des informations pour le Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the traitement des demandes individuelles de protection internationale. Il ne processing of individual applications for international protection. The traduit aucune politique ni n’exprime aucune opinion et ne prétend pas document does not contain policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass apporter de réponse définitive quant à la valeur d’une demande de protection judgment on the merits of the application for international protection. It follows internationale. Il a été rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices de l’Union the Common EU Guidelines for processing country of origin information (April européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) et il a été rédigé conformément aux dispositions légales en vigueur. 2008) and is written in accordance with the statutory legal provisions. Ce document a été élaboré sur la base d’un large éventail d’informations The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected publiques soigneusement sélectionnées dans un souci permanent de with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even recoupement des sources. L’auteur s’est efforcé de traiter la totalité des though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the aspects pertinents du sujet mais les analyses proposées ne visent pas text is not necessarily exhaustive. -

Shrinking Civic Space and the Role of Civil Society in Resolution of Conflict in Anglophone Cameroon

Shrinking Civic Space and the Role of Civil Society in Resolution of Conflict in Anglophone Cameroon James Kiven Kewir, Gordon Crawford, Maurice Beseng & Nancy Annan FINDINGS 1 Cover Image Figure 1: Lawyers from Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon protesting in late 2016 before escalation of Cameroon Anglophone conflict Photo credit: Eric Shu, BBC News (30/11/2020) https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/tori-55130468 2 FINDINGS Contents List of Figures 4 5. Challenges faced by CSOs 26 5.1 Administrative restrictions and control 26 Executive Summary 5 5.2 CSO-government relations and sector discord 26 1. Introduction 6 5.3 Security threats 27 5.4 Financial challenges 28 2. Conflict Resolution, Civil Society Organisations and Shrinking Civic Space 8 6. Strategies to Counter Shrinking 2.1 Armed conflict and conflict resolution 8 Civic Spaces 29 2.2 Civil society 8 6.1 Awareness raising by CSOs on their role 29 2.3 Peacebuilding from below 9 6.2 Documentation and quality of data 29 2.4 Shrinking civic space 10 6.3 Mobilisation, networking and coalition building 30 6.4 Training and sensitisation campaigns 30 3. Background to the Conflict and Civil Society in Cameroon 12 6.5 Dialogue and communication 31 3.1 Colonialism, decolonisation and the post-colonial state in Cameroon 12 7. Conclusion 32 3.2 Civil society and the quest for autonomy of English-speaking Cameroon 15 References 35 3.3 The state of civic space in Cameroon 17 4. Contributions of CSOs to the Resolution of Cameroon’s ‘Anglophone’ Conflict 20 4.1 Humanitarian action 20 4.2 Peace campaigns