E. S. Beesly Karl Marx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism Taylor, David Award date: 2010 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism by David C. Taylor, MA, FSA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD School of Arts Roehampton University 2010 Abstract Vernon Lushington (1832-1912) was a leading Positivist and disciple of Comte's Religion of Humanity. In The Religion of Humanity: The Impact of Comtean Positivism on Victorian Britain T.R. Wright observed that “the inner struggles of many of [Comte's] English disciples, so amply documented in their note books, letters, and diaries, have not so far received the close sympathetic treatment they deserve.” Material from a previously little known and un-researched archive of the Lushington family now makes possible such a study. -

Che Guevara's Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy

SOCIALIST VOICE / JUNE 2008 / 1 Contents 249. Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy. John Riddell 250. From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism. John Riddell 251. Bolivian President Condemns Europe’s Anti-Migrant Law. Evo Morales 252. Harvest of Injustice: The Oppression of Migrant Workers on Canadian Farms. Adriana Paz 253. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part One. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 254. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part Two. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 255. The Harper ‘Apology’ — Saying ‘Sorry’ with a Forked Tongue. Mike Krebs ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #249, June 8, 2008 Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy By John Riddell One of the most important developments in Cuban Marxism in recent years has been increased attention to the writings of Ernesto Che Guevara on the economics and politics of the transition to socialism. A milestone in this process was the publication in 2006 by Ocean Press and Cuba’s Centro de Estudios Che Guevara of Apuntes criticos a la economía política [Critical Notes on Political Economy], a collection of Che’s writings from the years 1962 to 1965, many of them previously unpublished. The book includes a lengthy excerpt from a letter to Fidel Castro, entitled “Some Thoughts on the Transition to Socialism.” In it, in extremely condensed comments, Che presented his views on economic development in the Soviet Union.[1] In 1965, the Soviet economy stood at the end of a period of rapid growth that had brought improvements to the still very low living standards of working people. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 115 No. 10 £1.50 December 2010 IS THE POPE ON A SLIPPERY SLOPE? As a thoughtful person, the Pope is concerned that males involved in certain activities might inadvertently spread the AIDS virus to their male friends. He has therefore apparently authorised them to employ condoms, thereby contradicting his organisation's propaganda that these articles are ineffective for this purpose. He also knows that the said activities are most unlikely to result in conception! The obvious next point to consider is the position of a woman whose husband may have the AIDS virus. The Pope has not authorised that the husband's virus should be similarly confined and his wife protected from danger. The Pope apparently considers that the divine requirement to conceive takes precedence, even if the child and its mother contract AIDS as a result. For how long can this absurd contradiction be maintained? VERNON LUSHINGTON, THE CRISIS OF FAITH AND THE ETII1CS OF POSITIVISM David Taylor 3 THE SPIRIT LEVEL DELUSION Christopher Snowdon 10 REVIEW: HUMANISM: A BEGINNER'S GUIDE by Peter Cave Charles Rudd 13 CLIMATE CHANGE, DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN NATURE Marek Kohn 15 VIEWPOINTS Colin Mills. Jim Tazewell 22 ETHICAL SOCIETY EVENTS 24 Centre for Inquiry UK and South Place Ethical Society present THE ROOT CAUSES OF THE HOLOCAUST What caused the Holocaust? What was the role of the Enlightenment? What role did religion play in causing, or trying to halt, the Holocaust? 1030 Registration 1100 Jonathan Glover 1200 David Ranan 1300 A .C. -

On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Wilson, M 2015 On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain. Architectural Histories, 3(1): 15, pp. 1–21, DOI: http:// +LVWRULHV dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.cr RESEARCH ARTICLE On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain Matthew Wilson* Positivism captured the Victorian imagination. Curiously, however, no work has focused on the architec- tural history and theory of Positivist halls in Britain. Scholars present these spaces of organised Positiv- ism as being the same in thought and action throughout their existence, from the 1850s to the 1940s. Yet the British Positivists’ inherently different views of the work of their leader, the French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857), caused such friction between them that a great schism in the movement occurred in 1878. By the 1890s two separate British Positivist groups were using different space and syntax types for manifesting a common goal: social reorganisation. The raison d’être of these institu- tions was to realize Comte’s utopian programme, called the Occidental Republic. In the rise of the first organised Positivist group in Britain, Richard Congreve’s Chapel Street Hall championed the religious ritu- alism and cultural festivals of Comte’s utopia; the terminus for this theory and practice was a temple typology, as seen in the case of Sydney Style’s Liverpool Church of Humanity. Following the Chapel Street Hall schism of 1878, Newton Hall was in operation by 1881 and under the direction of Frederic Harrison. Harrison’s group coveted intellectual and humanitarian activities over rigid ritualism; this tradition culmi- nated in a synthetic, multi-function hall typology, as seen in the case of Patrick Geddes’ Outlook Tower. -

On the Nationalisation of the Old English Universities

TH E NATIONALIZATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES LEWIS CAMPBELL, MA.LLD. /.» l.ibris K . DGDEN THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES J HALL & SON, Be> • ON THE NATIONALISATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES ON THE NATIONALISATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES BY LEWIS CAMPBELL, M.A., LL.D. EMERITUS PKOFESSOK OF GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. ANDREWS HONORARY FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD LONDON: CHAPMAN AND HALL 1901 LK TO CHARLES SAVILE ROUNDELL My dear Roundell, You have truly spoken of the Act, which forms the central subject of this book, as " a little measure that may boast great things." To you, more than to anyone now living, the success of that measure was due ; and without your help its progress could not here have been set forth. To you, therefore, as of right, the following pages are in- scribed. Yours very sincerely, LEWIS CAMPBELL PREFACE IN preparing the first volume of the Life of Benjamin fowett, I had access to documents which threw unexpected light on certain movements, especially in connexion with Oxford University- Reform. I was thus enabled to meet the desire of friends, by writing an article on " Some Liberal Move- ments of the Last Half-century," which appeared in the Fortnightly Review for March, 1900. And I was encouraged by the reception which that article met with, to expand the substance of it into a small book. Hence the present work. I have extended my reading on the subject, and have had recourse to all sources of information which I found available. -

(Xiv) in Retrospect

(XIV) IN RETROSPECT i]��C���-��UMAN experience would be falsified if the dreadful suffering which the six Tolpuddle Martyrs bore with such amazing fortitude had produced no result. Their conduct under trial was a challenge to the conscience of the nation. Their fidelity to principles that were in themselves the expression of elementary rights of citizenship rang like a clarion call to the workers of their own generation. They were certainly not the founders of Trades Unionism, whose origins go back many decades � Q��earlier than 1800. Nor were they the first Trades Unionists The martyrdom ��!!! an inspiration to be transported, but their example was an inspiration which has lost none of its power in the course of a century. The period immediately following the returnof the Dorsetshire labourers was one full of difficultyfor the Unions. The latter had been foremostin the agitation for a Parlia mentary inquiry into their status and operation, and in an effort to meet the criticism levelled against them many had removed the oath from their initiation ceremonies. A series of embittered industrial disputes had begun in 1834, notably that of the lockout of the silk workers at Derby, the strike of the gas workers in London and the lockout of the London building operatives. The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union crashed in the strain thrown upon its funds, and for a time it appeared that reaction had gained its way. Many of the skilled trades, however, maintained their organisation intact and gradually developed fromlocal organisation into national Unions exerting a considerable influence. It was a period demanding the utmost loyalty to the principles of Trade Unionism. -

Russian Emigration and British Marxist Socialism

WALTER KENDALL RUSSIAN EMIGRATION AND BRITISH MARXIST SOCIALISM Britain's tradition of political asylum has for centuries brought refugees of many nationalities to her shores. The influence both direct and indirect, which they have exerted on British life has been a factor of no small importance. The role of religious immigration has frequently been examined, that of the socialist emigres from Central Europe has so far received less detailed attention. Engels was a frequent contributor to the "Northern Star" at the time of the Chartist upsurge in the mid-icjth century,1 Marx also contributed.2 George Julian Harney and to a lesser extent other Chartist leaders were measurably influenced by their connection with European political exiles.3 At least one of the immigrants is reputed to have been involved in plans for a Chartist revolt.4 The influence which foreign exiles exerted at the time of Chartism was to be repro- duced, although at a far higher pitch of intensity in the events which preceded and followed the Russian Revolutions of March and October 1917. The latter years of the 19th century saw a marked increase of foreign immigration into Britain. Under the impact of antisemitism over 1,500,000 Jewish emigrants left Czarist Russia between 1881 and 1910, 500,000 of them in the last five years. The number of foreigners in the UK doubled between 1880 and 1901.5 Out of a total of 30,000 Russian, Polish and Roumanian immigrants the Home Office reported that no less than 8,000 had landed between June 1901 and June 1902.6 1 Mark Hovell, The Chartist Movement, Manchester 1925, p. -

H. M. Hyndman, E. B. Bax, and the Reception of Karl Marx's Thought In

1 H. M. Hyndman, E. B. Bax, and the Reception of Karl Marx’s Thought in Late-Nineteenth Century Britain, c. 1881-1893 Seamus Flaherty Queen Mary University of London Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Statement of Originality I, Seamus Flaherty, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Seamus Flaherty Date: 13. 09. 2017 3 Abstract This thesis examines how the idea of Socialism was remade in Britain during the 1880s. It does so with reference to the two figures most receptive to the work of Karl Marx, H. M. Hyndman and E. B. Bax. -

I!Lim Hill HW

Dh;tna.'.!ih 3: ;... GiIl::!I! Librar) 646~ I!lim Hill HW ~ill rua ~ Ii ~ (JIPE-PUNE 005464 A Short History of the British Working Class Movement A Short History of the Bri tish Working Class Movement 1789-1925 by G. D. H. Cole Volume It. 1848-1900 LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN AND UNWIN LIMITED & THE LABOUR PUBLISHING COMPANY LIMITED , x • F~·?- Pvblislte4 1926• .......... .. GUAT 811J7.... n TId WBlftJ1lUllll ....... "ft., t.OJlDO • .&a'D ~L PREFACE I HAD intended to complete in this second volume my short survey of the history of the British Working-class Movement. But, as soon as I began to reduce to order my accumulated material, I saw that it would be impossible to do this without making the second volume nearly twice as long as the first. It seemed, more over, that there was a natural break in the story just about the end of the century. The Victorian age appeared to be a chapter com plete in itself, and deserving to be dealt with as a rounded whole. I therefore decided to make a second break about 1900, and to complete my study in three volumes instead of two. Just as, in the first volume, I was trying to present a coherent account of the successive waves of working-class revolt against the new economic and social conditions created by the Industrial Revolution, so here I have attempted to present a picture of the new working-class movements which, from about 1850 onwards, based themselves on an acceptance of Industrialism, and an attempt to make the best of the new structure of economic society. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

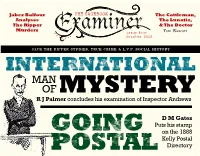

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

Towards a Unified Theory Analysing Workplace Ideologies: Marxism And

Marxism and Racial Oppression: Towards a Unified Theory Charles Post (City University of New York) Half a century ago, the revival of the womens movementsecond wave feminismforced the revolutionary left and Marxist theory to revisit the Womens Question. As historical materialists in the 1960s and 1970s grappled with the relationship between capitalism, class and gender, two fundamental positions emerged. The dominant response was dual systems theory. Beginning with the historically correct observation that male domination predates the emergence of the capitalist mode of production, these theorists argued that contemporary gender oppression could only be comprehended as the result of the interaction of two separate systemsa patriarchal system of gender domination and the capitalist mode of production. The alternative approach emerged from the debates on domestic labor and the predominantly privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power under capitalism. In 1979, Lise Vogel synthesized an alternative unitary approach that rooted gender oppression in the tensions between the increasingly socialized character of (most) commodity production and the essentially privatized character of the social reproduction of labor-power. Today, dual-systems theory has morphed into intersectionality where distinct systems of class, gender, sexuality and race interact to shape oppression, exploitation and identity. This paper attempts to begin the construction of an outline of a unified theory of race and capitalism. The paper begins by critically examining two Marxian approaches. On one side are those like Ellen Meiksins Wood who argued that capitalism is essentially color-blind and can reproduce itself without racial or gender oppression. On the other are those like David Roediger and Elizabeth Esch who argue that only an intersectional analysis can allow historical materialists to grasp the relationship of capitalism and racial oppression.