On the Nationalisation of the Old English Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Johns Hopkins University Circulars

[THIS NUMBER IS ESPECIALLY DEVOTED TO STATEMENTS OF THE WORK OF THE PAST YEAR AND TO THE PROGRAMMES FOR THE NEXT ACADEMIC YEAR.] JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY CIRCULARS. Pub/L~’/ied wit/i tAe approlation oft/ze Board of Trustees. No. 16.3 BALTIMORE, JULY, 1882. [PRICE5 CENTS. CALENDAR FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR, 1882-83. September 19. Next Term Begins. September 20—23. Examinations for I~Iatricu1ation. September 26. Instructions Resumed. June 9, Next TermCloses. CONTENTS. PAGE. PAGE. Mathematics: Ancient and Modern Languages: Work of the Past Year, 218 Programme in Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, etc. 228 Programme for the Next Year, 219 Programme in German 229 Physics: Programme in English, 280 Work of the Past Year, 220 Programme in the Romance Languages 280 Programme for the Next Year, 220 History and Political Science: Chemistry: Work of the Past Year, 281 Work of the Past Year, 221 Programme for the Next Year, . 282 Programme for the Next Year, 222 Philosophy, Ethics, etc.: Biology: Work of the Past Year, 283 Work of the Past Year, . 223 Programmes forthe Next Year, 233 Programme for the Next Year, 224 Recent Appointments 234 Ancientand Modern Languages: Collegiate Instruction 235 Work in Ancient Languages, . 226 Degrees Conferred, 286 Work in Modern Languages 227 JYLEETINGS OF SOCIETIES. Scientific. First Wednesday of each month, Metaphysical. Second Tuesday of each Mathematical. Third Wednesday of each at 8P.M. month, at 8P.M. month, at 8P.M. S. H. Freeman, Secretary. B. I. Gilman, Secretary. 0. H. Mitchell, Secretary. Naturalists’ Field Club. Excursionseach Philological. First Friday of each month, Historical andPoliticalScience. -

The Smith Family…

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO. UTAH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/smithfamilybeingOOread ^5 .9* THE SMITH FAMILY BEING A POPULAR ACCOUNT OF MOST BRANCHES OF THE NAME—HOWEVER SPELT—FROM THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY DOWNWARDS, WITH NUMEROUS PEDIGREES NOW PUBLISHED FOR THE FIRST TIME COMPTON READE, M.A. MAGDALEN COLLEGE, OXFORD \ RECTOR OP KZNCHESTER AND VICAR Or BRIDGE 50LLARS. AUTHOR OP "A RECORD OP THE REDEt," " UH8RA CCELI, " CHARLES READS, D.C.L. I A MEMOIR," ETC ETC *w POPULAR EDITION LONDON ELLIOT STOCK 62 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1904 OLD 8. LEE LIBRARY 6KIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO UTAH TO GEORGE W. MARSHALL, ESQ., LL.D. ROUGE CROIX PURSUIVANT-AT-ARM3, LORD OF THE MANOR AND PATRON OP SARNESFIELD, THE ABLEST AND MOST COURTEOUS OP LIVING GENEALOGISTS WITH THE CORDIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENTS OP THE COMPILER CONTENTS CHAPTER I. MEDLEVAL SMITHS 1 II. THE HERALDS' VISITATIONS 9 III. THE ELKINGTON LINE . 46 IV. THE WEST COUNTRY SMITHS—THE SMITH- MARRIOTTS, BARTS 53 V. THE CARRINGTONS AND CARINGTONS—EARL CARRINGTON — LORD PAUNCEFOTE — SMYTHES, BARTS. —BROMLEYS, BARTS., ETC 66 96 VI. ENGLISH PEDIGREES . vii. English pedigrees—continued 123 VIII. SCOTTISH PEDIGREES 176 IX IRISH PEDIGREES 182 X. CELEBRITIES OF THE NAME 200 265 INDEX (1) TO PEDIGREES .... INDEX (2) OF PRINCIPAL NAMES AND PLACES 268 PREFACE I lay claim to be the first to produce a popular work of genealogy. By "popular" I mean one that rises superior to the limits of class or caste, and presents the lineage of the fanner or trades- man side by side with that of the nobleman or squire. -

Jebb's Antigone

Jebb’s Antigone By Janet C. Collins A Thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Classics in conformity with the requirements for the Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August 2015 Copyright Janet Christine Collins, 2015 I dedicate this thesis to Ross S. Kilpatrick Former Head of Department, Classics, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. Who of us will forget his six-hour Latin exams? He was a very open-minded prof who encouraged us to think differently, he never criticized, punned us to death and was a thoroughly good chap. And to R. Drew Griffith My supervisor, not a punster, but also very open-minded, encouraged my wayward thinking, has read everything and is also a thoroughly good chap. And to J. Douglas Stewart, Queen’s Art Historian, sadly now passed away, who was more than happy to have long conversations with me about any period of history, but especially about the Greeks and Romans. He taught me so much. And to Mrs. Norgrove and Albert Lee Abstract In the introduction, chapter one, I seek to give a brief oversight of the thesis chapter by chapter. Chapter two is a brief biography of Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb, the still internationally recognized Sophoclean authority, and his much less well-known life as a humanitarian and a compassionate, human rights–committed person. In chapter three I look at δεινός, one of the most ambiguous words in the ancient Greek language, and especially at its presence and interpretation in the first line of the “Ode to Man”: 332–375 in Sophocles’ Antigone, and how it is used elsewhere in Sophocles and in a few other fifth-century writers. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism

DOCTORAL THESIS Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism Taylor, David Award date: 2010 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Vernon Lushington : Practising Positivism by David C. Taylor, MA, FSA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD School of Arts Roehampton University 2010 Abstract Vernon Lushington (1832-1912) was a leading Positivist and disciple of Comte's Religion of Humanity. In The Religion of Humanity: The Impact of Comtean Positivism on Victorian Britain T.R. Wright observed that “the inner struggles of many of [Comte's] English disciples, so amply documented in their note books, letters, and diaries, have not so far received the close sympathetic treatment they deserve.” Material from a previously little known and un-researched archive of the Lushington family now makes possible such a study. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 115 No. 10 £1.50 December 2010 IS THE POPE ON A SLIPPERY SLOPE? As a thoughtful person, the Pope is concerned that males involved in certain activities might inadvertently spread the AIDS virus to their male friends. He has therefore apparently authorised them to employ condoms, thereby contradicting his organisation's propaganda that these articles are ineffective for this purpose. He also knows that the said activities are most unlikely to result in conception! The obvious next point to consider is the position of a woman whose husband may have the AIDS virus. The Pope has not authorised that the husband's virus should be similarly confined and his wife protected from danger. The Pope apparently considers that the divine requirement to conceive takes precedence, even if the child and its mother contract AIDS as a result. For how long can this absurd contradiction be maintained? VERNON LUSHINGTON, THE CRISIS OF FAITH AND THE ETII1CS OF POSITIVISM David Taylor 3 THE SPIRIT LEVEL DELUSION Christopher Snowdon 10 REVIEW: HUMANISM: A BEGINNER'S GUIDE by Peter Cave Charles Rudd 13 CLIMATE CHANGE, DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN NATURE Marek Kohn 15 VIEWPOINTS Colin Mills. Jim Tazewell 22 ETHICAL SOCIETY EVENTS 24 Centre for Inquiry UK and South Place Ethical Society present THE ROOT CAUSES OF THE HOLOCAUST What caused the Holocaust? What was the role of the Enlightenment? What role did religion play in causing, or trying to halt, the Holocaust? 1030 Registration 1100 Jonathan Glover 1200 David Ranan 1300 A .C. -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

Volume 40, Number 1 the ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 1 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD Sydney Law School The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Charles Hamra, Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 1 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Illinois Classical Studies

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 880 V.2 Classics renew phaH=«= SS^S^jco The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN m\ k m OCT IS 386 Air, 1 ? i!;88 WOV 1 5 988 FEB 19 19! i^f' i;^ idi2 CLASSICS L161 — O-1096 ILLINOIS CLASSICAL STUDIES VOLUME II •977 Miroslav Marcovich, Editor UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana Chicago London 1 1977 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN :o-252-oo629- O ^ Xl^ Preface Volume II (1977) o( Illinois Classical Studies is a contribution of the clas- sicists from the University of Illinois to the celebration of the Bicentennial of the American Revolution (1776-1976). It comprises twenty-one select contributions by classical scholars from Ann Arbor, Berkeley, Cambridge (England), Cambridge (Massachusetts), Chicago, London, New York, Philadelphia, Providence, St. Andrews, Stanford, Swarthmore, Toronto, Urbana and Zurich. The publication of this volume was possible thanks to generous grants by Dean Robert W. Rogers (Urbana-Champaign) and Dean Elmer B. Hadley (Chicago Circle). Urbana, 4 July 1975 Miroslav Marcovich, Editor .. : Contents 1 The Nature of Homeric Composition i G. p. GOOLD 2. The Mare, the Vixen, and the Bee: Sophrosyne as the Virtue of Women in Antiquity 35 HELEN F. -

Good Men and True

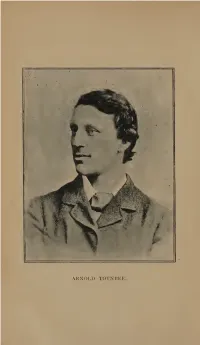

ARNOLD TOYNBEE. GOOD MEN AND TRUE BIOGRAPHIES OF WORKERS IN THE FIELDS OF BENEFICENCE AND BENEVOLENCE BY ALEXANDER H. JAPP, LL.D. AUTHOR OF “ GOLDEN LIVES,” “MASTER MISSIONARIES," “LIFE OF THOREAU,'' ETC.,’ ETC. SECOND EDITION. T. FISHER UNWIN TATERNOSTER SQUARE 1890 “ Men resemble the gods in nothing so much as in doing good to their fellow-creature—man.”—Cicero. 112053 3 1223 00618 4320 MY LITTLE FRIENDS AND CORRESPONDENTS, TOM, CARL, AND ANNE, GRANDCHILDREN OF THOMAS GUTHRIE, D.D., IN THE HOPE THAT THEY MAY NOT BE WHOLLY DISAPPOINTED WITH THE LITTLE SKETCH I HAVE, IN THIS VOLUME, TRIED TO MAKE OF THEIR REVERED GRANDFATHER, PARTLY FROM THE MEMOIR OF THEIR FATHER AND UNCLE, AND PARTLY FROM IMPRESSIONS OF MY OWN. Oh, young in years, in heart, and hope. May ye of lives like his be led. And find new courage, strength, and scope, In thoughts of him each step ye tread: And draw the line op goodness down Through long descent, to be your crown— A crown the greener that its roots are laid Deep in the past in fields your forbears made. CONTENTS. I PAGE NORMAN MACLEOD, D.D., preacljcr aim Unitor. 13 11. EDWARD DENISON, <£ast=<£nD CCIorLcr aim Social Reformer. 105 hi. ARNOLD TOYNBEE, Christian economist anti Klotiiers’ jFjctenl). 139 ,iv. JOHN CONINGTON, £*)djoIar aim Christian Socialist. 175 v. CHARLES KINGSLEY, Christian Pastor ann /Bofcefist. 197 IO CONTENTS. PAGE VI. JAMES HANNINGTON, SSiggtotiarp 'Bishop attn Crabeiier. 239 VII. THE STANLEYS—FATHER AND SON : Ecclesiastics ann IReformcrgs. 271 VIII. THOMAS GUTHRIE, D.D., Preacher ann jFounDer of 3Rag;gen Schools in Eninlntrgh- 311 IX. -

Who, Where and When: the History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow

Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow Compiled by Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond © University of Glasgow, Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond, 2001 Published by University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ Typeset by Media Services, University of Glasgow Printed by 21 Colour, Queenslie Industrial Estate, Glasgow, G33 4DB CIP Data for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 0 85261 734 8 All rights reserved. Contents Introduction 7 A Brief History 9 The University of Glasgow 9 Predecessor Institutions 12 Anderson’s College of Medicine 12 Glasgow Dental Hospital and School 13 Glasgow Veterinary College 13 Queen Margaret College 14 Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama 15 St Andrew’s College of Education 16 St Mungo’s College of Medicine 16 Trinity College 17 The Constitution 19 The Papal Bull 19 The Coat of Arms 22 Management 25 Chancellor 25 Rector 26 Principal and Vice-Chancellor 29 Vice-Principals 31 Dean of Faculties 32 University Court 34 Senatus Academicus 35 Management Group 37 General Council 38 Students’ Representative Council 40 Faculties 43 Arts 43 Biomedical and Life Sciences 44 Computing Science, Mathematics and Statistics 45 Divinity 45 Education 46 Engineering 47 Law and Financial Studies 48 Medicine 49 Physical Sciences 51 Science (1893-2000) 51 Social Sciences 52 Veterinary Medicine 53 History and Constitution Administration 55 Archive Services 55 Bedellus 57 Chaplaincies 58 Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery 60 Library 66 Registry 69 Affiliated Institutions