Freedom of the Seas in the Arctic Region 219

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

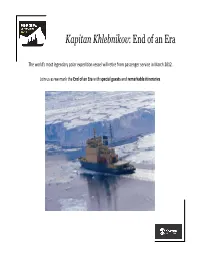

End of an Eraagent

Kapitan Khlebnikov: End of an Era The world’s most legendary polar expedition vessel will retire from passenger service in March 2012. Join us as we mark the End of an Era with special guests and remarkable itineraries. 2 Only 112 people will participate in any one of these historic voyages. As a former guest you can save 5% off the published price of these remarkable expeditions, and be one of the very few who will be able to say—I was on the Khlebnikov at the End of an Era. The legendary icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov will retire as an expedition vessel in March 2012, returning to escort duty for ships sailing the Northeast Passage. As Quark's flagship, the vessel has garnered more polar firsts than any other passenger ship. Under the command of Captain Petr Golikov, Khlebnikov circumnavigated the Antarctic continent, twice. The ship was the platform for the first tourism exploration of the Dry Valleys. The icebreaker has transited the Northwest Passage more than any other expedition ship. Adventurers aboard Khlebnikov were the first commercial travelers to witness a total eclipse of the sun from the isolation of the Davis Sea in Antarctica. In 2004, the special attributes of Kapitan Khlebnikov made it possible to visit an Emperor Penguin rookery in the Weddell Sea that had not been visited for 40 years. 3 End of an Era at a Glance Itineraries Start End Special Guests Northwest Passage: West to East July 18, 2010 August 5, 2010 Andrew Lambert, author of The Gates of Hell: Sir John Franklin’s Tragic Quest for the Northwest Passage. -

Itinerary Route: Reykjavik, Iceland to Reykjavik, Iceland

ICELAND AND GREENLAND: WILD COASTS AND ICY SHORES Itinerary route: Reykjavik, Iceland to Reykjavik, Iceland 13 Days Expeditions in: Aug Call us at 1.800.397.3348 or call your Travel Agent. In Australia, call 1300.361.012 • www.expeditions.com DAY 1: Reykjavik, Iceland / Embark padding Special Offers Arrive in Reykjavík, the world’s northernmost capital, which lies only a fraction below the Arctic Circle and receives just four hours of sunlight in FREE BAR TAB AND CREW winter and 22 in summer. Check in to our group TIPS INCLUDED hotel in the morning and take time to rest and We will cover your bar tab and all tips for refresh before lunch. In the afternoon, take a the crew on all National Geographic panoramic drive through the city’s Old Town Resolution, National Geographic before embarking National Explorer, National Geographic Geographic Endurance. (B,L,D) Endurance, and National Geographic Orion voyages. DAY 2: Flatey Island padding Explore Iceland’s western frontier by Zodiac cruise, visiting Flatey Island, a trading post for many centuries. In the afternoon, sail past the wild and scenic coast of Iceland’s Westfjords region. (B,L,D) DAY 3: Arnafjörður and Dynjandi Waterfall padding In the early morning our ship will glide into beautiful Arnafjörður along the northwest coast of Iceland. For a more active experience, disembark early and hike several miles along the base of the fjord to visit spectacular Dynjandi Waterfall. Alternatively, join our expedition staff on the bow of the ship as we venture ever deeper into the fjord and then go ashore by Zodiac to walk up to the base of the waterfall. -

South Dakota Rangelands: More Than a Sea of Grass

212 RANGELANDS 18(6), December 1996 South Dakota Rangelands: More than a Sea of Grass F. Robert Gartner and Carolyn Hull Sieg re-settlement explorers described the region's land- the continent. Elevation increases from about 900 to 1,500 scape as a "sea of grass." Yet, this "sea" was quite feet above sea level along the eastern border to 3,000 to p varied, and included a wealth of less obvious forested 3,500 feet along the western border. The highest point in communities. Both physiographic and climatic gradients the United States east of the Rocky Mountains is Harney across the state of South Dakota contributed to the devel- Peak in the Black Hills at 7,241 feet elevation. opment of variable vegetation types of South Dakota. The The major portion of the state lies within the Great Plains diverse flora truly identifies the state as a "Land of Infinite physiographicprovince (Fig. 1), and a smaller portion in the Variety." Variations in climate, soils, and topography help to Central Lowlands Province (Denson 1964). The Great accentuate this label. Large herbivores such as bison and Plains Province is a broad highland that slopes gradually periodic fires ignited by lightning and American Indians also eastward from the Rocky Mountains on the west to the contributed to the formation of the pre-settlement land- Central Lowlands on the east. That portion of the Great scape. Plains Province in the western two-thirds of South Dakota has been termed the Missouri Plateau by some authors. The Central Lowlands Province extends from the drainage Climate Topography, Physiography, basin of the James River (approximatelythe 99th Meridian) eastward. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Marine Debris in the Coastal Environment of Iceland´S Nature Reserve, Hornstrandir - Sources, Consequences and Prevention Measures

Master‘s thesis Marine Debris in the Coastal Environment of Iceland´s Nature Reserve, Hornstrandir - Sources, Consequences and Prevention Measures Anna-Theresa Kienitz Advisor: Hrönn Ólína Jörundsdóttir University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, May 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Hrönn Ólína Jörundsdóttir Ph.D Matis Ltd. Food and Biotech Vinlandsteid 12, 143 Rekavík Reader: Dr. Helgi Jensson Ráðgjafi, Senior consultant Skrifstofa forstjóra, Human Resources Secretariat Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Academic Director of Coastal and Marine Management Anna-Theresa Kienitz Marine Debris in the Coastal Environment of Iceland´s Nature Reserve, Hornstrandir - Sources, Consequences and Prevention Measures 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Anna-Theresa Kienitz All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, May 2013 Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. ________________________ Theresa Kienitz Abstract Marine debris is a growing problem, which adversely affects ecosystems and economies world-wide. Studies based on a standardized approach to examine the quantity of marine debris are lacking at many locations, including Iceland. In the present study, 26 transects were established on six different bays in the north, west and south of the nature reserve Hornstrandir in Iceland, following the standardized approach developed by the OSPAR Commission. -

The Lore of the Stars, for Amateur Campfire Sages

obscure. Various claims have been made about Babylonian innovations and the similarity between the Greek zodiac and the stories, dating from the third millennium BCE, of Gilgamesh, a legendary Sumerian hero who encountered animals and characters similar to those of the zodiac. Some of the Babylonian constellations may have been popularized in the Greek world through the conquest of The Lore of the Stars, Alexander in the fourth century BCE. Alexander himself sent captured Babylonian texts back For Amateur Campfire Sages to Greece for his tutor Aristotle to interpret. Even earlier than this, Babylonian astronomy by Anders Hove would have been familiar to the Persians, who July 2002 occupied Greece several centuries before Alexander’s day. Although we may properly credit the Greeks with completing the Babylonian work, it is clear that the Babylonians did develop some of the symbols and constellations later adopted by the Greeks for their zodiac. Contrary to the story of the star-counter in Le Petit Prince, there aren’t unnumerable stars Cuneiform tablets using symbols similar to in the night sky, at least so far as we can see those used later for constellations may have with our own eyes. Only about a thousand are some relationship to astronomy, or they may visible. Almost all have names or Greek letter not. Far more tantalizing are the various designations as part of constellations that any- cuneiform tablets outlining astronomical one can learn to recognize. observations used by the Babylonians for Modern astronomers have divided the sky tracking the moon and developing a calendar. into 88 constellations, many of them fictitious— One of these is the MUL.APIN, which describes that is, they cover sky area, but contain no vis- the stars along the paths of the moon and ible stars. -

Exposing the Structure of an Arctic Food Web Helena K

Exposing the structure of an Arctic food web Helena K. Wirta1,†, Eero J. Vesterinen2,†, Peter A. Hamback€ 3, Elisabeth Weingartner3, Claus Rasmussen4, Jeroen Reneerkens5,6, Niels M. Schmidt6, Olivier Gilg7,8 & Tomas Roslin1 1Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Latokartanonkaari 5, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland 2Department of Biology, University of Turku, Vesilinnantie 5, FI-20014 Turku, Finland 3Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 4Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 114, DK–8000 Aarhus, Denmark 5Conservation Ecology Group, Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Life Sciences, University of Groningen, P.O. Box 11103, 9700 CC Groningen, The Netherlands 6Arctic Research Centre, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Frederiksborgvej 399, DK-4000 Roskilde, Denmark 7Laboratoire Biogeosciences, UMR CNRS 6282, Universite de Bourgogne, 6 Boulevard Gabriel, 21000 Dijon, France 8Groupe de Recherche en Ecologie Arctique, 16 rue de Vernot, 21440 Francheville, France Keywords Abstract Calidris, DNA barcoding, generalism, Greenland, Hymenoptera, molecular diet How food webs are structured has major implications for their stability and analysis, Pardosa, Plectrophenax, specialism, dynamics. While poorly studied to date, arctic food webs are commonly Xysticus. assumed to be simple in structure, with few links per species. If this is the case, then different parts of the web may be weakly connected to each other, with Correspondence populations and species united by only a low number of links. We provide the Helena K. Wirta, Department of Agricultural first highly resolved description of trophic link structure for a large part of a Sciences, University of Helsinki, Latokartanonkaari 5, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland. high-arctic food web. -

Magnetic North: Artists and the Arctic Circle

Magnetic north Artists And the Arctic circle On view May 28, 2014 through August 29, 2014 Magnetic North is organized by The Arctic Circle in association with The Farm, Inc. The exhibition is sponsored by the 1285 Avenue of the Americas Art Gallery, in partnership with Jones Lang LaSalle, as a community based public service. IN MEMORY OF TERRY ADKINS (1953–2014) 2013 Arctic Circle Expedition Sarah Anne Johnson Circling the Arctic, 2011 Magnetic North How do people imagine the landscapes they find themselves in? How does the land shape the imaginations of people who dwell in it? How does desire itself, the desire to comprehend, shape knowledge? —Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams he Arctic Circle is a non-profit expeditionary residency program that brings together international groups of artists, writers, composers, architects, scientists, and educators. For Tseveral weeks each year, participants voyage into the open seas and fjords of the Svalbard archipelago aboard a specially equipped sailing vessel. The voyagers live and work together, aiding one another in the daily challenges of conducting research and creating new work based on their experiences. The residency is both a journey of discovery and a laboratory for the convergence of ideas and disciplines. Magnetic North comprises a selection of works by more than twenty visual and sound artists from the 2009–2012 expeditions. The exhibition encompasses a wide range of artistic practices, including photography, video, sound recordings, performance documentation, painting, sculpture, and kinetic and interactive installations. Taken together, the works of art offer unique and diverse perspectives on a part of the world rarely seen by others, conveying the desire to comprehend and interpret a largely uninhabitable and unknowable place. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2020 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2020 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 7 April 2021 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 starting in the Pacific Ocean to reach the Atlantic Oceam, but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 319 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2020 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (marked ‘cp’). -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Arctic Passage 1 the Northwest Passage Is the Sea Route Linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans

Original broadcast: February 28, 2006 BEFORE WATCHING Arctic Passage 1 The Northwest Passage is the sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Franklin Expedition traveled from England PROGRAM OVERVIEW to western Greenland through what NOVA recreates the expeditions of Sir is now Baffin Bay, then on to Resolute Island. Some believe the John Franklin and Roald Amundsen, crew made it as far as King William two Arctic explorers who set out to Island. Have students plot the fi nd the legendary Arctic sea route Northwest Passage on a map known as the Northwest Passage. and estimate its distance. 2 Organize the class into five teams. Hour one of the program: As they watch the program, have • tells how Sir John Franklin and his British Admiralty crew of 128 men four of the teams track one of the set out in May of 1845 with two ships to fi nd the mythical route following types of evidence related to why the expedition failed: connecting the Atlantic and Pacifi c Oceans. diseases, health issues and physical • notes the food and other provisions brought on the journey. remains; ship-related artifacts; Inuit • presents the types of evidence that historians relied on to determine testimony; and written notes and what happened to the expedition—artifacts that included a written journals. Have a fifth group keep track of when events occurred. note, ice core data, interviews with Inuit, and forensic analysis of body remains. • pieces together an account of where expedition members traveled and how they may have died. AFTER WATCHING • explains how Franklin and 20 percent of his crew died two years into 1 Have students refer to their notes the expedition; the fi nal four crew members died after six years on the ice.