The Production of Lateness Production the Analysis with Cultural Gerontology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanities and Posthumanism

english edition 1 2015 The Humanities and Posthumanism issue editor GRZEGORZ GROCHOWSKI MICHAł PAWEł MARKOWSKI Humanities: an Unfinished Project E WA DOMAńSKA Ecological Humanities R YSZARD NYCZ Towards Innovative Humanities: The Text as a Laboratory. Traditions, Hypotheses, Ideas O LGA CIELEMęCKA Angelus Novus Looks to the Future. On the Anti-Humanism Which Overcomes Nothingness SYZ MON WRÓBEL Domesticating Animals: A Description of a Certain Disturbance teksty drugie · Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science index 337412 · pl issn 0867-0633 EDITORIAL BOARD Agata Bielik-Robson (uk), Włodzimierz Bolecki, Maria Delaperrière (France), Ewa Domańska, Grzegorz Grochowski, Zdzisław Łapiński, Michał Paweł Markowski (usa), Maciej Maryl, Jakub Momro, Anna Nasiłowska (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Leonard Neuger (Sweden), Ryszard Nycz (Editor-in-Chief), Bożena Shallcross (usa), Marta Zielińska, Tul’si Bhambry (English Translator and Language Consultant), Justyna Tabaszewska, Marta Bukowiecka (Managing Editor) ADVISORY BOARD Edward Balcerzan, Stanisław Barańczak (usa) , Małgorzata Czermińska, Paweł Dybel, Knut Andreas Grimstad (Norway), Jerzy Jarzębski, Bożena Karwowska (Canada), Krzysztof Kłosiński, Dorota Krawczyńska, Vladimir Krysinski (Canada), Luigi Marinelli (Italy ), Arent van Nieukerken (Holland), Ewa Rewers, German Ritz (Switzerland), Henryk Siewierski (Brasil), Janusz Sławiński , Ewa Thompson (usa), Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Tamara Trojanowska (Canada), Alois Woldan (Austria), Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska ADDRESS Nowy Świat 72, room. -

The Location of “The Author” in John Barth's LETTERS

The Author’s Metamorphosis: The Location of “the Author” in John Barth’s LETTERS Naoto KOJIMA Abstract 1979 年に発表されたジョン・バースの浩瀚な小説『レターズ』は、トマス・ピンチョ ンの『重力の虹』と並び、アメリカ文学におけるポストモダン小説の極点として考えら れている。『レターズ』をリアリズムと(ポスト)モダニズム的言語実験との綜合を試 みる小説とする議論を踏まえながら、この論文は、それ以前のバース作品に特徴的な自 己言及的メタフィクションが問題とした、「作者」の位置についての矛盾との関係にお いて『レターズ』の達成を捉える。そしてそのメタフィクションの矛盾からの脱却が、 小説の構造的なレベルだけでなく物語内容のレベルにおいても、作中に登場する「作者」 の正体を巡る謎解きのプロットとして表れていることを示す。手紙の書き手の一人であ る「作者」こそが、物語中での不在の息子ヘンリー・バーリンゲイム7世にほかならず、 その両者がテクストの内部と外部を行き来する作者の「変身」によって特徴づけられて いるのである。従来の研究ではこの小説における「作者」の正体(と小説の構造との関 係)を十分に突き止められてはおらず、その点でこの『レターズ』論は一つの新たな作 品解釈の提示であり、同時に、小説における「作者」の位置づけを巡る考察でもある。 Key Words: author, metafiction, presence/absence, realism, postmodernism 1. Introduction John Barth is a highly self-conscious writer. From the beginning of his career, his fiction has shown a distinctive self-referential nature. In his first novel, The Floating Opera, Todd Andrews mourns the dilemma of writing his own story in a Tristram Shandy-like manner: “Good heavens, how does one write a novel! I mean, how can anybody stick to the story, if he’s at all sensitive to the significances of things?…[E]very new sentence I set down is full of figures and implications that I’d love nothing better than to chase to their dens with you, but such chasing would involve new figures and new chases, so that I’m sure we’d never get the story started, much less ended, if I let my inclinations run unleashed” (2). He realizes that it is impossible to tell the story completely. Telling a story holds an inevitable difference between the telling and the told. - 251 - His self-reflective fictions derive from this acknowledgement of painful resignation. In his career as a writer, Barth’s orientation toward a self-referential structure is inextricably interwoven with his failed effort to write an autobiographical novel. -

Speaking of Myth. an Interview with John Barth

SPEAKING OF MYTH. AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN BARTH CRISTINA GARRIGÓS GONZÁLEZ Universidad de León John Barth is probably the most important American postmodemist author writing nowadays: The prime maximalist of American Fiction as some critics have called him. Bom in Cambridge, Maryland in 1930, he is the author of ten novéis - The Sot-Weed Factor (1960) or Letters (1980) among them - a series of short fictions {Lost in the Funhouse, 1968^, a volume of novellas (Chimera, 1972), and two collections of non-fiction {The Friday Book, 1984 and Further Fridays, 1995). His works Th? Floating Opera and Lost in the Funhouse were finalist for the National Book Award in fiction, which he won in 1973 mth Chimera. Interviews with Barth usually center around his last book, a work in process or his opinión on Postmodemism, a task to which he dedicated his two seminal essays "The Literature of Exhaustion" and "The Literature of Replenishment". But in this interview, conducted in León during a visit of the author to our country, Barth discusses his relationship with four literary figures, which he has acknowledged as the "four regnant deities in his personal pantheon."^ These icons are in literary-historical order Odysseus, Scheherazade, Don Quixote and Huckleberry Finn. For him, there is no fifth, yet. These figures have appeared recurrently in his works: as characters, as surrogates for them, and he has discussed widely their relevance in his work in his numerous essays. The admiration of Barth for these mythological icons, "the four compass-points of my narrative imagination" as he calis them, is not half-hazard. -

Heide Ziegler

Heide Ziegler John Barth: Ironischer Repräsentant der .Postmoderne' John Barth ist einer der bedeutendsten Vertreter der literarischen ,Postmoderne'. Der Ausdruck ,Postmoderne' hat sich nicht unwesent hch an seinem Werk entwickelt und diesem umgekehrt repr'.isentativen Charakter verliehen. Die Suche nach einer Konstante in Barths sich wan delnden intellektuellen Positionen und emotionalen Dispositionen zwischen 1955, dem Jahr als er seine ersten beiden Romane schrieb, und 1984, dem Jahr seiner bislang letzten Publikation, dürfte somit einer Suche nach dem potentiellen Kern dieses ambivalenten, sowohl experiment- als auch traditionsorientierten Zweigs der zeitgenössischen amerikanischen Literatur gleichkommen; und der Facettenreichtum von Barths Obsessionen - Grenzbestimmungen zwischen Imagination und Wirklichkeit, Geschichte und Mythos, Literatur und Gesellschaft - ist umgekehrt das Ergebnis der diesem Kern inhärenten Anregungsener gie. Immer wenn sich daher Barth die Frage stellt, was die .Postmoderne' eigentlich sei, sucht er in bewußtem Narzißmus das objektive Korrelat seiner selbst in einem vielfältig gebrochenen allgemeinen Spiegelbild. Barth definiert die Anfangs- und vorläufige Endphase seiner eige nen literarischen Entwicklung in zwei komplementären theoretischen Abhandlungen. Die Ausgangsposition beschreibt er in "The Litera ture of Exhaustion" (1967), einer inzwischen zu einem Manifest der ,Postmoderne' gewordenen Hommage a Jorge Luis Borges. Barth be wundert Borges, denn .. his artistlc vlctOry. if you Iike. is that he con fronts an intellectual dead end and employs it against itself to ac complish new human work". I Ähnlich sucht Barth selbst in The Sot Weed Factor (1960) und Gi/es Goat-Boy (1966) die Sterilität histo rischer, beziehungsweise metaphysischer Klischees genau durch deren exuberanten Einsatz ironisch zu entlarven und zugleich zu transzendieren. Barths vorläufige theoretische Endposition dagegen findet sich in "The Literature of Replenishment: Postmodernist Fiction" (1980). -

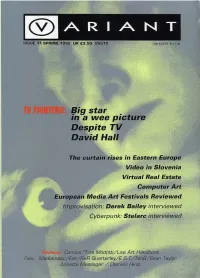

Variant Issue 11 Spring 1992

A R I /K N T ISSUE 11 SPRING 1992 UK £3.50 US$10 CAN $10.95 IRS4.00 mm FIGHTERS Big star in a wee pictur Despite T David Hal The cur ises in Eastern Eu Video in Slovenia Virtual Real Estate Computer Art m>m European Media Art Festivals Reviewed Improvisation: Derek Bailey interviewed Cyberpunk: Stelarc interviewed illii mm »«««<: Comics/Tina Modotti/Live Art Handboo Felix, Mediamatie/Ear/ReR Ouarterley/E. S. T/Ten8/Sean Taylor Annette Messaoer / Damien Hirst EDITORIAL QUOTES 4 Variant is a magazine of cross- NEWS currents in culture: art practice, 6 media, critical ideas, imaginative FESTIVAL and independent tendencies. We CALENDAR are a charitable project and 8 publish four times a year with the REPORT assistance of grants, advertising The Great British Mistake and sales. Most items are com- Vague + Vagabond Reviewed missioned, but we weicome con- 10 tributions and ideas for news items, reviews, articles, inter- DESPITE TV views, and polemical writing. INTERVIEWED BY MALCOLM DICKSON Guidelines for writers are avail- 16 able. We also welcome ideas for MEDIA MOGULS artists pages and for items which we can distribute within the MENTAL POLLUTION magazine, such as stickers, DON COUTTS + STUART COSGROVE prints, xerox work and other INTERVIEWED BY DOUG AUBREY ephemera. VIDEO FROM SLOVENIA Deadline for issue 1 2 is MARINA GRZINIC May 1 5th (Contributions) May 29th (Advertising) 26 THE CURTAIN RISES To advertise call 041 221 6380. ROLAND MILLER Rates for B & and colour W 28 available. FALSE PERSPECTIVES Subscriptions are £14 for four IN VIRTUAL SPACE issues (individuals) £20 for four SEAN CUBITT issues (institutions) 32 MAUSOLEA + ALTARed NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS STATES JEREMY WELSH Doug Aubrey is a freelance video/TV Director Jochen Coldewey is a writer and curator living in 36 Germany. -

Social Tension As a Creative Necessity in the Fiction of Hawthorne, James, and Joyce

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1988 Lessons of the Masters: Social Tension as a Creative Necessity in the Fiction of Hawthorne, James, and Joyce. Craig Arthur Milliman Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Milliman, Craig Arthur, "Lessons of the Masters: Social Tension as a Creative Necessity in the Fiction of Hawthorne, James, and Joyce." (1988). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4660. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4660 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Tristan and Isolde. Death by Rogelio De Egusquiza

Tristan and Isolde. Death by Rogelio de Egusquiza Lourdes Jiménez This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona: fig. 7 © Biblioteca Nacional de España: figs. 4 and 5 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa – Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: fig. 1 © Galerie Elstir: fig. 3 © MAS | Museo de Arte Moderno y Contemporáneo de Santander y Cantabria: fig. 2 © Mixed Media. Community Museum of Ixelles: fig. 8 © Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels / photo: J. Geleyns – Ro scan: fig. 6 Text published in: Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 10, 2016, pp. 145-170. Sponsor: 2 “Musical drama is the complement to a painting, it is a living image in which it fuses with the drama of the musical expression, aiming to achieve the truth that arises from intelligence and culture...” Rogelio de Egusquiza1 he painter Rogelio de Egusquiza y Barrena was born on 20 July 1845 in Santander. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE ARTIST, MYTH AND SOCIETY IN THE CONTEMPORARY SPANISH NOVEL, 1945-2010 A Dissertation in Spanish by Katie Jean Vater © 2014 Katie Jean Vater Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 ! ii The dissertation of Katie Jean Vater was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew J. Marr Graduate Program Director Associate Professor of Spanish Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee William R. Blue Professor of Spanish Maria Truglio Associate Professor of Italian Guadalupe Martí-Peña Senior Lecturer in Spanish Charlotte Houghton Associate Professor of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Since the Early Modern period, artists have drawn, painted, and sculpted their way through the pages of Spanish literature. Seventeenth-century Spanish theater reveals both practical and aesthetic value for such characters; while authors, particularly playwrights, utilized artist characters for literary ends, they concurrently allied themselves with real artists fighting for greater social recognition for their work and allowed their artists characters to express those concerns on the page as well as on the stage. The development of the artist novel and the Künstlerroman (the novel of artistic development) in the nineteenth century reflected not only the achievement of social recognition sought by artists of prior generations, but also the development of the Romantic “charismatic myth of the artist,” which would go on to characterize general societal perception of artists (and their literary representations) for the next century. While the artist figure never disappears from Spanish literary production, the scholarly study of such figures wanes in current contemporary investigation. -

Ana-Maria DELIU Faculty of Letters, Babeș-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, Romania [email protected]

Ana-Maria DELIU Faculty of Letters, Babeș-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, Romania [email protected] TRANSGRESSIVE METAFICTION: DECONSTRUCTING WORLDS IN JOYCE’S ULYSSES AND BARTH’S LOST IN THE FUNHOUSE Abstract: The question “to what degree does metafiction construct and deconstruct worlds” generates a conceptual and paradigmatic rethinking of metafiction, based on the theoretical tools of possible worlds theory, especially fictional worlds. More specifically, to what degree does metafiction succeed in constructing a verisimilar possible world or, on the contrary, undress it of materiality and illusion of reality, turning rather to itself as a text (metafiction is self-conscious, auto-referential fiction, drawing attention to its mechanisms and its status as an artifact while a possible world is a world which is credible, ontologically different from ours only in being non-actualised). Moreover, in metafictions like James Joyce‟s Ulysses, or John Barth‟s Lost in the funhouse, deconstructing worlds means not only de-materialising worlds, turning to form in an extremely overt way, and moving from mimesis of product to mimesis of process, but also the French deconstruction praxis of denouncing structuralist dichotomy signified-signifier, thus loosing oneself in a network of signifiers which ultimately destroy the metaphysics of the signified. After poststructuralism murders the author, the latter revives as a practical fiction in a textual world of indecidables. Key words: fiction theory, transgressive metafiction, deconstruction, practical fiction, James Joyce, John Barth Dematerialisation and Deconstruction Firstly, I would like to mention that I wrote this study in relationship with another one published in the first issue of Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory (50-60). -

Keeping House with Louise Nevelson

Keeping House with Louise juliNevelsona lson Julia Bryan-Wilson Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oaj/article-abstract/40/1/109/3813334 by Colby College user on 08 November 2017 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oaj/article-abstract/40/1/109/3813334 by Colby College user on 08 November 2017 Keeping House with Louise Nevelson Julia Bryan-Wilson In 1972 and 1973, Louise Nevelson built a series of sculptures that she entitled 1. There is no definitive catalogue raisonne´of Dream Houses.1 For these works, she utilised her most well-known artistic pro- Nevelson’s oeuvre, but according to Jean Lipman, there are thirty-seven total works in this cess: she accreted small bits of wood into a larger construction that she then series; Jean Lipman, Nevelson’s World (New York, painted a solid, unifying colour – in this case, as with most but not all of her NY: Hudson Hills Press, 1983), p. 65. Seven art, black (Fig. 1). One such piece, Dream House XXXII (1972), is tall and nar- Dream House sculptures, all dated 1972, were on row, topped with a gabled roof. Featuring small flaps mounted with metal display at Nevelson’s retrospective at the Walker Art Center in 1973; see the checklist in Martin hinges, it is permeable in several ways – not only because of its variously acces- Friedman, Nevelson: Wood Sculptures (New York, sible multiple entrances (‘doors’ or ‘windows’ that can be open or shut), but NY: E.P.Dutton & Co., 1973), pp. 69–70. also because its walls are shot through with apertures that make the entire en- closure riven with passages of contrasting lights and darks to create a dense, geometric visual field. -

Grieving Artists: Influences of Loss and Bereavement on Visual Artmaking

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Dissertations (GSASS) Winter 1-15-2021 Grieving Artists: Influences of Loss and Bereavement on Visual Artmaking Rebecca Arnold [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Rebecca, "Grieving Artists: Influences of Loss and Bereavement on Visual Artmaking" (2021). Expressive Therapies Dissertations. 107. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations/107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 Grieving Artists: Influences of Loss and Bereavement on Visual Artmaking A DISSERTATION (submitted by) REBECCA ARNOLD In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LESLEY UNIVERSITY January 15, 2021 2 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at Lesley University and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations form this dissertation are allowed without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of sources is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation form or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Solo Exhibitions, Site-Specific Projects & Performance. (Selection)

Solo exhibitions, site-specific projects Tangente, Burgos, Spain. January and february & performance. (Selection) 2021. _______________________________________ This list has been chronologically compounded, individual expositions and performance preceding group exhibitions, art biennial and performance. 2020 _______________________________________ Solo exhibitions, site-specific projects & performance. (Selection) 2021 Act of Disobedience. Fabra i Coats Solo exhibitions, site-specific projects & Contemporary art centre of Barcelona, Barcelona. December 2020. performance. (Selection) The first step. Las Naves Art Centre, Valencia, Abel Azcona Maledetto. Una visione Spain. December 2020. retrospettiva del lavoro censurato e perseguitato dell’artista. Palazzo delle Arti, Naples, Italy. September 2021. Act of disobedience. La Panera Art Centre, Lleida, Spain. November 2020. La Savia. Aldama-Fabre Gallery, Bilbao, Spain. September 2021. Spain asks for forgiveness. Contemporary Art Museum of Bogotá, Colombia. Exhibition second Spain Asks for Forgiveness. Somos Gallery, stage performative work. October 2020. Ambactia Project, Berlin, Germany. Mayo 2021. Amen or The Pederasty. La Panera Abel Azcona. Calderón Theatre, Valladolid, Contemporary Art Centre of de Lleida, Cataluña. Spain. May 2021. Censored Collection Exhibition by Tatxo Benet. September 2020. Abel Azcona | 15 Essential Pieces. Calderón Theatre, Valladolid, Spain. May 2021. Spain asks for forgiveness. Urban Spree Gallery, Berlín, Alemania. Site-specific project. Empathy and Prostitution. Arsenal of Venice, August 2020. Venice, Italy. October 2021. The Line. Lamosa Space, Cuenca, España. Solo Brushwood. White Lab Contemporary Art Space, exhibition with the collaboration of the Cuenca Madrid, Spain. April 2021. Fine Arts Faculty. June 2020. Abel Azcona. Selected Works: 1988-2018. Montegrande Gallery, Santiago de Chile, Chile. Spain asks for forgiveness. Contemporary Art March 2021. Museum of Bogotá, Colombia.