Keeping House with Louise Nevelson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera

How To Quote This Material ©Jack Fritscher www.JackFritscher.com Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera — Take 2: Pentimento for Robert Mapplethorpe Manuscript TAKE 2 © JackFritscher.com PENTIMENTO FOR ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE FETISHES, FACES, AND FLOWERS Of EVIL1 “He wanted to see the devil in us all... The man who liberated S&M Leather into international glamor... The man Jesse Helms hates... The man whose epic movie-biography only Ken Russell could re-create...” Photographer Mapplethorpe: The Whitney, the NEA and censorship, Schwarzenegger, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Paloma Picasso, Hockney, Warhol, Patti Smith, Scavullo, sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, S&M, flowers, black leather, fists, Allen Ginsberg, and, once-upon-a-time, me... The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently a dozen years ago. The High Time was in full upswing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here. In 1977, Robert Mapplethorpe arrived unexpectedly in my life. I was editor of the San Francisco—based international leather magazine, Drummer, and Robert was a New York shock-and-fetish photographer on the way up. Drummer wanted good photos. Robert, already infamous for his leather S&M portraits, always seeking new models with outrageous trips, wanted more specific exposure within the leather community. Our mutual, professional want ignited almost instantly into mutual, personal passion. -

C100 Trip to Houston

Presented in partnership with: Trip Participants Doris and Alan Burgess Tad Freese and Brook Hartzell Bruce and Cheryl Kiddoo Wanda Kownacki Ann Marie Mix Evelyn Neely Yvonne and Mike Nevens Alyce and Mike Parsons Your Hosts San Jose Museum of Art: S. Sayre Batton, deputy director for curatorial affairs Susan Krane, Oshman Executive Director Kristin Bertrand, major gifts officer Art Horizons International: Leo Costello, art historian Lisa Hahn, president Hotel St. Regis Houston Hotel 1919 Briar Oaks Lane Houston, Texas, 77027 Phone: 713.840.7600 Houston Weather Forecast (as of 10.31.16) Wednesday, 11/2 Isolated Thunderstorms 85˚ high/72˚ low, 30% chance of rain, 71% humidity Thursday, 11/3 Partly Cloudy 86˚ high/69˚ low, 20% chance of rain, 70% humidity Friday, 11/4 Mostly Sunny 84˚ high/63 ˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 60% humidity Saturday, 11/5 Mostly Sunny 81˚ high/61˚ low, 0% chance of rain, 42% humidity Sunday, 11/6 Partly Cloudy 80˚ high/65˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 52% humidity Day One: Wednesday, November 2, 2016 Dress: Casual Independent arrival into George Bush Intercontinental/Houston Airport. Here in “Bayou City,” as the city is known, Houstonians take their art very seriously. The city boasts a large and exciting collection of public art that includes works by Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Heizer, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, Claes Oldenburg, Albert Paley, and Tony Rosenthal. Airport to hotel transportation: The St. Regis Houston Hotel offers a contracted town car service for airport pickup for $120 that would be billed directly to your hotel room. -

Arnold) Glimcher, 2010 Jan

Oral history interview with Arne (Arnold) Glimcher, 2010 Jan. 6-25 Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Arne Glimcher on 2010 January 6- 25. The interview took place at PaceWildenstein in New York, NY, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by the Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Arne Glimcher has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Arne Glimcher on Wednesday, January the sixth, at Pace Wildenstein Gallery on— ARNOLD GLIMCHER: 32 East 57th Street. MR. McELHINNEY: 32 East 57th Street in New York City. Hello. MR. GLIMCHER: Hi. MR. McELHINNEY: One of the questions I like to open with is to ask what is your recollection of the first time you were in the presence of a work of art? MR. GLIMCHER: Can't recall it because I grew up with some art on the walls. So my mother had some things, some etchings, Picasso and Chagall. So I don't know. -

October 30 – December 30, 2021

ST 71 OCTOBER 30 – DECEMBER 30, 2021 EXHIBITION 71st A•ONE – A•ONE is a national competition/exhibition highlighting the diversity of work that is currently being made by established and emerging artists. Eligibility – Open to all artists, 18 years of age and older, residing in the United States. Original artwork in any media will be considered. Giclée reproductions of original works will not be accepted. Eligible artwork must have been completed after January 1, 2019, and fall within the restrictions. Awards – Grand Prize, awards an artist a solo exhibition at Silvermine Arts Center with a $1,000 stipend for show related expenses. The Juror has additional awards to give at their discretion. Entry Fee – $50 for up to 5 entries. To be considered for the Grand Prize Award, artists are required to enter a minimum of three works. Online entry – Complete the 71st A•ONE entry form on Slideroom – https://silvermineart.slideroom.com JUROR Richard Klein is a curator, artist, and writer. Since 1999 he has been Exhibitions Director of The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In his two decade long career as a curator of contemporary art he has organized over 80 exhibitions, including solo shows of the work of Janine Antoni, Sol LeWitt, Mark Dion, Roy Lichtenstein, Hank Willis Thomas, Brad Kahlhamer, Kim Jones, Jack Whitten, Jessica Stockholder, Tom Sachs, and Elana Herzog. Major curatorial projects at The Aldrich have included Fred Wilson: Black Like Me (2006), No Reservations: Native American History and Culture in Contemporary Art (2006), Elizabeth Peyton: Portrait of an Artist (2008), Shimon Attie: MetroPAL.IS. -

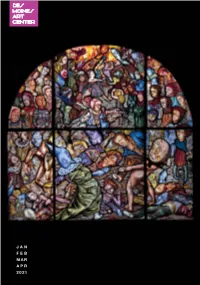

Jan Feb Mar Apr 2021 from the Director

FROM THE DIRECTOR JAN FEB MAR APR 2021 FROM THE DIRECTOR Submit your story I am sure you would agree, let us put 2020 behind us and anticipate a better year in 2021. With this expectation in mind, your Art Center teams are moving ahead with major plans for the new year. Our exhibitions We continue to include The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s accept personal Stained-Glass Art; Justin Favela: Central American; stories in response and Louis Fratino: Tenderness revealed along with to Black Stories. Iowa Artists 2021: Olivia Valentine. An array of print gallery and permanent collections projects, including Enjoy this story an exhibition that showcases our newly conserved submission from painting by Francisco Goya, Don Manuel Garcia de Candace Williams. la Prada, 1811, and another that features our works by Claes Oldenburg, will augment and complement Seen. I felt seen as I walked these projects. The exhibitions will continue to through the Black Stories address our goals of being an inclusive and exhibition with my friend. welcoming institution, while adding to the scholarship As history and experiences of the field, engaging our local communities in were shared through art, meaningful ways, and providing a site for the I remembered my mom community to gather together, at least virtually taking my sister and I to (for now), to share ideas and perspectives. the California African- Our Black Stories project has done just this American Museum often. as we continue to receive personal stories from She would buy children’s the community for possible inclusion in a books written by Black publication. -

The Humanities and Posthumanism

english edition 1 2015 The Humanities and Posthumanism issue editor GRZEGORZ GROCHOWSKI MICHAł PAWEł MARKOWSKI Humanities: an Unfinished Project E WA DOMAńSKA Ecological Humanities R YSZARD NYCZ Towards Innovative Humanities: The Text as a Laboratory. Traditions, Hypotheses, Ideas O LGA CIELEMęCKA Angelus Novus Looks to the Future. On the Anti-Humanism Which Overcomes Nothingness SYZ MON WRÓBEL Domesticating Animals: A Description of a Certain Disturbance teksty drugie · Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science index 337412 · pl issn 0867-0633 EDITORIAL BOARD Agata Bielik-Robson (uk), Włodzimierz Bolecki, Maria Delaperrière (France), Ewa Domańska, Grzegorz Grochowski, Zdzisław Łapiński, Michał Paweł Markowski (usa), Maciej Maryl, Jakub Momro, Anna Nasiłowska (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Leonard Neuger (Sweden), Ryszard Nycz (Editor-in-Chief), Bożena Shallcross (usa), Marta Zielińska, Tul’si Bhambry (English Translator and Language Consultant), Justyna Tabaszewska, Marta Bukowiecka (Managing Editor) ADVISORY BOARD Edward Balcerzan, Stanisław Barańczak (usa) , Małgorzata Czermińska, Paweł Dybel, Knut Andreas Grimstad (Norway), Jerzy Jarzębski, Bożena Karwowska (Canada), Krzysztof Kłosiński, Dorota Krawczyńska, Vladimir Krysinski (Canada), Luigi Marinelli (Italy ), Arent van Nieukerken (Holland), Ewa Rewers, German Ritz (Switzerland), Henryk Siewierski (Brasil), Janusz Sławiński , Ewa Thompson (usa), Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Tamara Trojanowska (Canada), Alois Woldan (Austria), Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska ADDRESS Nowy Świat 72, room. -

Cassandra Langer Interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec

NYFAI - Interview: Cassandra Langer interviewed by Katie Cercone Date: Dec. 15th, 2008 K.C. This is December 15th, 2008, Katie Cercone interviewing Cassandra Langer. C.L. I think it was important for most of us during the early 70s when the movement started up to establish institutions that would be accommodating to the radical new ideas that we had. We rejected the idea of accepting the old roles; of getting married being wives, and mothers . I think it’s hard for young people to understand that was the life you were groomed for. If you aspired to anything else, you were deemed oddball out , rushed off to a psychoanalyst or worse yet, thrown into a mental institution for readjustment. Establishing the Feminist Art Institute was an extremely revolutionary thing to do at that time. NYFAI provided a safe space for creative women who were trying to break out of those stereotypes. There was the California site that my friend Arlene Raven and others including Mimi Schapiro and Judy Chicago set up within the heart of a traditionally patriarchal art department spawning Woman House and other alternative spaces. Mimi, Nancy and people in New York, set up their own versions to begin with but they evolved into the Feminist Art Institute. For people like myself who were outsider-insiders, because I was teaching in South Carolina in the heart of limitation land and bigotry it was an oasis. The freedom of being able to talk with like-minded people was empowering. Founding the Collage Art Association’s Women’s Caucus for Art helped a lot. -

California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2199r38x No online items Guide prepared by Abigail Dixon for History Associates Incorporated California Institute of the Arts California Institute of the Arts Archive California Institute of the Arts 24700 McBean Parkway Valencia, California 91355-2397 Phone: (661) 253-7882 Fax: (661) 254-4561 Email: [email protected] URL: http://calarts.edu/library/collections/archive 2008 CalArts-003 1 Administrative Summary Creator: California Institute of the Arts Title: California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection Dates: 1971-2007 Date (bulk): (bulk 1972-1977) Quantity: 2.3 cubic feet Repository: California Institute of the Arts. Library. Valencia, California 91355-2397 Abstract: The California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection contains articles, brochures, correspondence, exhibition catalogs, invoices, newsletters, and other materials documenting the influence of feminism on the training of artists and the making of art. The collection covers the years 1971 to 2007 with the bulk of the material ranging from 1972 to 1977. California Institute of the Arts Archive Identification: CalArts-003 Language of Material: English Restrictions on Access This collection is open for research with permission from California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Publication Rights Property rights and literary rights reside with California Institute of the Arts. For permission to reproduce or to publish, please contact California Institute of the Arts Archive staff. Related Material Located in the California Institute of the Arts Archive Archives Unprocessed collections with related material are located in the CalArts Library Archives. Preferred Citation California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Materials Collection. -

LOUISE NEVELSON SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2018 Epic Abstraction

LOUISE NEVELSON SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2018 Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, The Met Fifth Avenue, New York, opened December 17, 2018. Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C., November 4, 2018– August 18, 2019. Kindred Spirits: Louise Nevelson & Dorothy Hood, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, November 3, 2018– February 3, 2019. The Masters: Art Students League Teachers and Their Students, Hirschl & Adler, New York, October 18– December 1, 2018. (Catalogue) Summer Group Show, Pace Gallery, Seoul, June 5–August 11, 2018. LeWitt, Nevelson, Pendleton Part II, Pace Gallery, Geneva, May 16–July 13, 2018. Dark Place of Dreams: Louise Nevelson with Chakaia Booker, Lauren Fensterstock and Kate Gilmore, Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville, A Cultural Institute of University of North Florida, April 28– September 2, 2018. (Catalogue) LeWitt, Nevelson, Pendleton, Pace Gallery, Geneva, March 21–May 4, 2018. 2017 Louise Nevelson: Selected Group Exhibitions 2 Function to Freedom: Quilts and Abstract Expressions, Sara Kay Gallery, New York, December 1, 2017– January 13, 2018. Black and White: Louise Nevelson/Pedro Guerrero, Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine, October 6, 2017–April 1, 2018. American Sculpture: Sotheby’s Beyond Limits, Chatsworth, Derbyshire, United Kingdom, September 15– November 12, 2017. Vaginal Davis & Louise Nevelson: Chimera, Invisible-Exports, New York, September 8–October 22, 2017. 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, July 22–December 31, 2017. To Distribute and Multiply: The Feibes & Schmitt Gift, The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, opens on June 10, 2017. Multiple Impressions, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, June 10–August 5, 2017. -

Curriculum Vitae Table of Contents

CURRICULUM VITAE Revised February 2015 ADRIAN MARGARET SMITH PIPER Born 20 September 1948, New York City TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Educational Record ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Languages...................................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Philosophy Dissertation Topic.................................................................................................................. 2 4. Areas of Special Competence in Philosophy ......................................................................................... 2 5. Other Areas of Research Interest in Philosophy ................................................................................... 2 6. Teaching Experience.................................................................................................................................... 2 7. Fellowships and Awards in Philosophy ................................................................................................. 4 8. Professional Philosophical Associations................................................................................................. 4 9. Service to the Profession of Philosophy .................................................................................................. 5 10. Invited Papers and Conferences in Philosophy ................................................................................. -

Feminist Art Education: Made in California

Feminist Art Education: Made in California by Judy Chicago ’ve often stated that it I thought that if my situation was similar to Iwould have been im- that of other women, then perhaps my strug- possible to conceive of, gle might serve as a model for the struggle much less implement, the out of gendered conditioning that a woman 1970/71 Fresno Feminist would have to make if she were to realize Art Program anywhere but herself artistically. I was sure that this process California. One reason for would take some time. Therefore, I set up the this became evident in the Fresno program with the idea that I would 2000 Los Angeles County work intensely with the fifteen women I chose Museum of Art exhibit on as students. 100 years of art in Califor- nia, whose title I borrowed It’s important to take a moment to comment for this chapter. The Made on the climate for women at that time. There in California show demon- were no Women’s Studies courses, nor any un- strated some of the unique derstanding that women had their own his- qualities of California cul- tory. In fact, attitudes might be best under- ture, notably, an open- stood through the story of a class in European ness to new ideas that is Intellectual History I had taken in the early less prominently found in 1960s, while I was an undergraduate at UCLA. the East, where the white, At the first class meeting, the professor said male, Eurocentric tradi- he would talk about women’s contributions tion has a longer legacy at the end of the semester. -

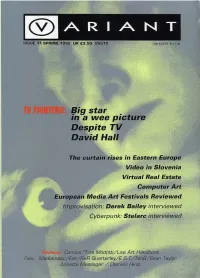

Variant Issue 11 Spring 1992

A R I /K N T ISSUE 11 SPRING 1992 UK £3.50 US$10 CAN $10.95 IRS4.00 mm FIGHTERS Big star in a wee pictur Despite T David Hal The cur ises in Eastern Eu Video in Slovenia Virtual Real Estate Computer Art m>m European Media Art Festivals Reviewed Improvisation: Derek Bailey interviewed Cyberpunk: Stelarc interviewed illii mm »«««<: Comics/Tina Modotti/Live Art Handboo Felix, Mediamatie/Ear/ReR Ouarterley/E. S. T/Ten8/Sean Taylor Annette Messaoer / Damien Hirst EDITORIAL QUOTES 4 Variant is a magazine of cross- NEWS currents in culture: art practice, 6 media, critical ideas, imaginative FESTIVAL and independent tendencies. We CALENDAR are a charitable project and 8 publish four times a year with the REPORT assistance of grants, advertising The Great British Mistake and sales. Most items are com- Vague + Vagabond Reviewed missioned, but we weicome con- 10 tributions and ideas for news items, reviews, articles, inter- DESPITE TV views, and polemical writing. INTERVIEWED BY MALCOLM DICKSON Guidelines for writers are avail- 16 able. We also welcome ideas for MEDIA MOGULS artists pages and for items which we can distribute within the MENTAL POLLUTION magazine, such as stickers, DON COUTTS + STUART COSGROVE prints, xerox work and other INTERVIEWED BY DOUG AUBREY ephemera. VIDEO FROM SLOVENIA Deadline for issue 1 2 is MARINA GRZINIC May 1 5th (Contributions) May 29th (Advertising) 26 THE CURTAIN RISES To advertise call 041 221 6380. ROLAND MILLER Rates for B & and colour W 28 available. FALSE PERSPECTIVES Subscriptions are £14 for four IN VIRTUAL SPACE issues (individuals) £20 for four SEAN CUBITT issues (institutions) 32 MAUSOLEA + ALTARed NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS STATES JEREMY WELSH Doug Aubrey is a freelance video/TV Director Jochen Coldewey is a writer and curator living in 36 Germany.