Orbital Forcing Timescales: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

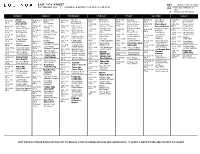

E a S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T August 2021 Schedule

E A S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T KEY St udi o key on bac k SEPT EM BER 2021 SC H ED U LE EF F EC T IVE 09.01.21–09.30.21 Bolld New Class, Instructor, or Time ♦ Advance sign-up required M O NDA Y T UE S DA Y W E DNE S DA Y T HURS DA Y F RII DA Y S A T URDA Y S UNDA Y Atthllettiic Master of One Athletic 6:30–7:15 METCON3 6:15–7:00 Stacked! 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 8:30–9:30 Vinyasa Yoga 6:15–7:00 6:30–7:15 6:15–7:00 Condiittiioniing Gerard Conditioning MS ♦ Kevin Scott MS ♦ Steve Mitchell CS ♦ Mike Harris YS ♦ Esco Wilson MS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Stteve Miittchellll Thelemaque Boyd Melson 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 7:00–7:45 Pilates Fusion 8:30–9:15 Piillattes Remiix 9:00–9:45 Cardio Sculpt 6:30–7:15 Cycle Beats 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 6:30–7:15 Cycle Power CS ♦ Candace Peterson YS ♦ Mia Wenger YS ♦ Sammiie Denham MS ♦ Cindya Davis CS ♦ Serena DiLiberto CS ♦ Shweky CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:15–8:15 Vinyasa Yoga 7:45–8:30 Firestarter + Best Firestarter + Best 9:30–10:15 Cycle Power 7:15–8:05 Athletic Yoga Off The Barre Josh Mathew- Abs Ever 9:00–9:45 CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:00–8:00 Vinyasa Yoga 7:00–7:45 YS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Abs Ever YS ♦ Elitza Ivanova YS ♦ Margaret Schwarz YS ♦ Sarah Marchetti Meier Shane Blouin Luke Bernier 10:15–11:00 Off The Barre Gleim 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 8:45–9:45 Vinyasa Yoga Cycle Power YS ♦ Cindya Davis Gerard 7:15–8:00 Precision Run® TR ♦ Kevin Scott YS ♦ Colleen Murphy 9:15–10:00 CS ♦ Nikki Bucks TR ♦ CS ♦ Candace 10:30–11:15 Atletica Thelemaque TR ♦ Chaz Jackson Peterson 8:45–9:30 Pilates Fusion 8:00–8:45 -

To What Extent Can Orbital Forcing Still Be Seen As the “Pacemaker Of

Sophie Webb To what extent can orbital forcing still be seen as the main driver of global climate change? Introduction The Quaternary refers to the last 2.6 million years of geological time. During this period, there have been many oscillations in global climate resulting in episodes of glaciation and fluctuations in sea level. By examining evidence from a range of sources, palaeoclimatic data across different timescales can be considered. The recovery of longer, better preserved sediment and ice cores in addition to improved dating techniques have shown that climate has changed, not only on orbital timescales, but also on shorter scales of centuries and decades. Such discoveries have lead to the most widely accepted hypothesis of climate change, the Milankovitch hypothesis, being challenged and the emergence of new explanations. Causes of Climate Change Milankovitch Theory Orbital mechanisms have little effect on the amount of solar radiation (insolation) received by Earth. However, they do affect the distribution of this energy around the globe and produce seasonal variations which promote the growth or retreat of glaciers and ice sheets. Eccentricity is an approximate 100 kyr cycle and refers to the shape of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The orbit can be more elliptical or circular, altering the time Earth spends close to or far from the Sun. This in turn affects the seasons which can initiate small climatic changes. Seasonal changes are also caused by the Earth’s precession which runs on a cycle of around 23 kyr. The effect of precession is influenced by the eccentricity cycle: when the orbit is round, Earth’s distance from the sun is constant so there is not a hugely significant precessional effect. -

Late Pliocene Climate Variability on Milankovitch to Millennial Time Scales: a High-Resolution Study of MIS100 from the Mediterranean

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 228 (2005) 338–360 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Late Pliocene climate variability on Milankovitch to millennial time scales: A high-resolution study of MIS100 from the Mediterranean Julia Becker *, Lucas J. Lourens, Frederik J. Hilgen, Erwin van der Laan, Tanja J. Kouwenhoven, Gert-Jan Reichart Department of Stratigraphy–Paleontology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, Netherlands Received 10 November 2004; received in revised form 19 June 2005; accepted 22 June 2005 Abstract Astronomically tuned high-resolution climatic proxy records across marine oxygen isotope stage 100 (MIS100) from the Italian Monte San Nicola section and ODP Leg 160 Hole 967A are presented. These records reveal a complex pattern of climate fluctuations on both Milankovitch and sub-Milankovitch timescales that oppose or reinforce one another. Planktonic and benthic foraminiferal d18O records of San Nicola depict distinct stadial and interstadial phases superimposed on the saw-tooth pattern of this glacial stage. The duration of the stadial–interstadial alterations closely resembles that of the Late Pleistocene Bond cycles. In addition, both isotopic and foraminiferal records of San Nicola reflect rapid changes on timescales comparable to that of the Dansgard–Oeschger (D–O) cycles of the Late Pleistocene. During stadial intervals winter surface cooling and deep convection in the Mediterranean appeared to be more intense, probably as a consequence of very cold winds entering the Mediterranean from the Atlantic or the European continent. The high-frequency climate variability is less clear at Site 967, indicating that the eastern Mediterranean was probably less sensitive to surface water cooling and the influence of the Atlantic climate system. -

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado

Geochronology Database for Central Colorado Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geochronology Database for Central Colorado By T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt Data Series 489 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: T.L. Klein, K.V. Evans, and E.H. DeWitt, 2009, Geochronology database for central Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 489, 13 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

Milankovitch and Sub-Milankovitch Cycles of the Early Triassic Daye Formation, South China and Their Geochronological and Paleoclimatic Implications

Gondwana Research 22 (2012) 748–759 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Gondwana Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gr Milankovitch and sub-Milankovitch cycles of the early Triassic Daye Formation, South China and their geochronological and paleoclimatic implications Huaichun Wu a,b,⁎, Shihong Zhang a, Qinglai Feng c, Ganqing Jiang d, Haiyan Li a, Tianshui Yang a a State Key Laboratory of Geobiology and Environmental Geology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China b School of Ocean Sciences, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing 100083 , China c State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China d Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA article info abstract Article history: The mass extinction at the end of Permian was followed by a prolonged recovery process with multiple Received 16 June 2011 phases of devastation–restoration of marine ecosystems in Early Triassic. The time framework for the Early Received in revised form 25 November 2011 Triassic geological, biological and geochemical events is traditionally established by conodont biostratigra- Accepted 2 December 2011 phy, but the absolute duration of conodont biozones are not well constrained. In this study, a rock magnetic Available online 16 December 2011 cyclostratigraphy, based on high-resolution analysis (2440 samples) of magnetic susceptibility (MS) and Handling Editor: J.G. Meert anhysteretic remanent magnetization (ARM) intensity variations, was developed for the 55.1-m-thick, Early Triassic Lower Daye Formation at the Daxiakou section, Hubei province in South China. The Lower Keywords: Daye Formation shows exceptionally well-preserved lithological cycles with alternating thinly-bedded mud- Early Triassic stone, marls and limestone, which are closely tracked by the MS and ARM variations. -

Plio-Pleistocene Imprint of Natural Climate Cycles in Marine Sediments

Lebreiro, S. M. 2013. Plio-Pleistocene imprint of natural climate cycles in marine sediments. Boletín Geológico y Minero, 124 (2): 283-305 ISSN: 0366-0176 Plio-Pleistocene imprint of natural climate cycles in marine sediments S. M. Lebreiro Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, OPI. Dept. de Investigación y Prospectiva Geocientífica. Calle Ríos Rosas, 23, 28003-Madrid, España [email protected] ABSTracT The response of Earth to natural climate cyclicity is written in marine sediments. The Earth is a complex system, as is climate change determined by various modes, frequency of cycles, forcings, boundary conditions, thresholds, and tipping elements. Oceans act as climate change buffers, and marine sediments provide archives of climate conditions in the Earth´s history. To read climate records they must be well-dated, well-calibrated and analysed at high-resolution. Reconstructions of past climates are based on climate variables such as atmospheric composi- tion, temperature, salinity, ocean productivity and wind, the nature and quality which are of the utmost impor- tance. Once the palaeoclimate and palaeoceanographic proxy-variables of past events are well documented, the best results of modelling and validation, and future predictions can be obtained from climate models. Neither the mechanisms for abrupt climate changes at orbital, millennial and multi-decadal time scales nor the origin, rhythms and stability of cyclicity are as yet fully understood. Possible sources of cyclicity are either natural in the form of internal ocean-atmosphere-land interactions or external radioactive forcing such as solar irradiance and volcanic activity, or else anthropogenic. Coupling with stochastic resonance is also very probable. -

Downloaded 10/01/21 10:31 PM UTC 874 JOURNAL of CLIMATE VOLUME 12

MARCH 1999 VAVRUS 873 The Response of the Coupled Arctic Sea Ice±Atmosphere System to Orbital Forcing and Ice Motion at 6 kyr and 115 kyr BP STEPHEN J. VAVRUS Center for Climatic Research, Institute for Environmental Studies, University of WisconsinÐMadison, Madison, Wisconsin (Manuscript received 2 February 1998, in ®nal form 11 May 1998) ABSTRACT A coupled atmosphere±mixed layer ocean GCM (GENESIS2) is forced with altered orbital boundary conditions for paleoclimates warmer than modern (6 kyr BP) and colder than modern (115 kyr BP) in the high-latitude Northern Hemisphere. A pair of experiments is run for each paleoclimate, one with sea-ice dynamics and one without, to determine the climatic effect of ice motion and to estimate the climatic changes at these times. At 6 kyr BP the central Arctic ice pack thins by about 0.5 m and the atmosphere warms by 0.7 K in the experiment with dynamic ice. At 115 kyr BP the central Arctic sea ice in the dynamical version thickens by 2±3 m, accompanied bya2Kcooling. The magnitude of these mean-annual simulated changes is smaller than that implied by paleoenvironmental evidence, suggesting that changes in other earth system components are needed to produce realistic simulations. Contrary to previous simulations without atmospheric feedbacks, the sign of the dynamic sea-ice feedback is complicated and depends on the region, the climatic variable, and the sign of the forcing perturbation. Within the central Arctic, sea-ice motion signi®cantly reduces the amount of ice thickening at 115 kyr BP and thinning at 6 kyr BP, thus serving as a strong negative feedback in both pairs of simulations. -

The Global Monsoon Across Time Scales Mechanisms And

Earth-Science Reviews 174 (2017) 84–121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev The global monsoon across time scales: Mechanisms and outstanding issues MARK ⁎ ⁎ Pin Xian Wanga, , Bin Wangb,c, , Hai Chengd,e, John Fasullof, ZhengTang Guog, Thorsten Kieferh, ZhengYu Liui,j a State Key Laboratory of Mar. Geol., Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China b Department of Atmospheric Sciences, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96825, USA c Earth System Modeling Center, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China d Institute of Global Environmental Change, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an 710049, China e Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA f CAS/NCAR, National Center for Atmospheric Research, 3090 Center Green Dr., Boulder, CO 80301, USA g Key Laboratory of Cenozoic Geology and Environment, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 9825, Beijing 100029, China h Future Earth, Global Hub Paris, 4 Place Jussieu, UPMC-CNRS, 75005 Paris, France i Laboratory Climate, Ocean and Atmospheric Studies, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China j Center for Climatic Research, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The present paper addresses driving mechanisms of global monsoon (GM) variability and outstanding issues in Monsoon GM science. This is the second synthesis of the PAGES GM Working Group following the first synthesis “The Climate variability Global Monsoon across Time Scales: coherent variability of regional monsoons” published in 2014 (Climate of Monsoon mechanism the Past, 10, 2007–2052). -

The Effect of Orbital Forcing on the Mean Climate and Variability of the Tropical Pacific

15 AUGUST 2007 T I MMERMANN ET AL. 4147 The Effect of Orbital Forcing on the Mean Climate and Variability of the Tropical Pacific A. TIMMERMANN IPRC, SOEST, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii S. J. LORENZ Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany S.-I. AN Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea A. CLEMENT RSMAS/MPO, University of Miami, Miami, Florida S.-P. XIE IPRC, SOEST, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii (Manuscript received 24 October 2005, in final form 22 December 2006) ABSTRACT Using a coupled general circulation model, the responses of the climate mean state, the annual cycle, and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon to orbital changes are studied. The authors analyze a 1650-yr-long simulation with accelerated orbital forcing, representing the period from 142 000 yr B.P. (before present) to 22 900 yr A.P. (after present). The model simulation does not include the time-varying boundary conditions due to ice sheet and greenhouse gas forcing. Owing to the mean seasonal cycle of cloudiness in the off-equatorial regions, an annual mean precessional signal of temperatures is generated outside the equator. The resulting meridional SST gradient in the eastern equatorial Pacific modulates the annual mean meridional asymmetry and hence the strength of the equatorial annual cycle. In turn, changes of the equatorial annual cycle trigger abrupt changes of ENSO variability via frequency entrainment, resulting in an anticorrelation between annual cycle strength and ENSO amplitude on precessional time scales. 1. Introduction Recent greenhouse warming simulations performed with ENSO-resolving coupled general circulation mod- The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a els (CGCMs) have revealed that the projected ampli- coupled tropical mode of interannual climate variability tude and pattern of future tropical Pacific warming that involves oceanic dynamics (Jin 1997) as well as (Timmermann et al. -

Equation of Time — Problem in Astronomy M

This paper was awarded in the II International Competition (1993/94) "First Step to Nobel Prize in Physics" and published in the competition proceedings (Acta Phys. Pol. A 88 Supplement, S-49 (1995)). The paper is reproduced here due to kind agreement of the Editorial Board of "Acta Physica Polonica A". EQUATION OF TIME | PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY M. Muller¨ Gymnasium M¨unchenstein, Grellingerstrasse 5, 4142 M¨unchenstein, Switzerland Abstract The apparent solar motion is not uniform and the length of a solar day is not constant throughout a year. The difference between apparent solar time and mean (regular) solar time is called the equation of time. Two well-known features of our solar system lie at the basis of the periodic irregularities in the solar motion. The angular velocity of the earth relative to the sun varies periodically in the course of a year. The plane of the orbit of the earth is inclined with respect to the equatorial plane. Therefore, the angular velocity of the relative motion has to be projected from the ecliptic onto the equatorial plane before incorporating it into the measurement of time. The math- ematical expression of the projection factor for ecliptic angular velocities yields an oscillating function with two periods per year. The difference between the extreme values of the equation of time is about half an hour. The response of the equation of time to a variation of its key parameters is analyzed. In order to visualize factors contributing to the equation of time a model has been constructed which accounts for the elliptical orbit of the earth, the periodically changing angular velocity, and the inclined axis of the earth. -

Research on the Precession of the Equinoxes and on the Nutation of the Earth’S Axis∗

Research on the Precession of the Equinoxes and on the Nutation of the Earth’s Axis∗ Leonhard Euler† Lemma 1 1. Supposing the earth AEBF (fig. 1) to be spherical and composed of a homogenous substance, if the mass of the earth is denoted by M and its radius CA = CE = a, the moment of inertia of the earth about an arbitrary 2 axis, which passes through its center, will be = 5 Maa. ∗Leonhard Euler, Recherches sur la pr´ecession des equinoxes et sur la nutation de l’axe de la terr,inOpera Omnia, vol. II.30, p. 92-123, originally in M´emoires de l’acad´emie des sciences de Berlin 5 (1749), 1751, p. 289-325. This article is numbered E171 in Enestr¨om’s index of Euler’s work. †Translated by Steven Jones, edited by Robert E. Bradley c 2004 1 Corollary 2. Although the earth may not be spherical, since its figure differs from that of a sphere ever so slightly, we readily understand that its moment of inertia 2 can be nonetheless expressed as 5 Maa. For this expression will not change significantly, whether we let a be its semi-axis or the radius of its equator. Remark 3. Here we should recall that the moment of inertia of an arbitrary body with respect to a given axis about which it revolves is that which results from multiplying each particle of the body by the square of its distance to the axis, and summing all these elementary products. Consequently this sum will give that which we are calling the moment of inertia of the body around this axis.