Heating up the Planet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Diagnosis & Treatment

1 DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT DIAGNOSIS STAGE III & STAGE IV COLORECTAL CANCER YOUR GUIDE IN THE FIGHT If you have recently been diagnosed with stage III or IV colorectal cancer (CRC), or have a loved one with the disease, this guide will give you invaluable information about how to interpret the diagnosis, realize your treatment options, and plan your path. You have options, and we will help you navigate the many decisions you will need to make. Your Guide in the Fight is a three-part book designed to empower and point you towards trusted, credible resources. Your Guide in the Fight offers information, tips, and tools to: DISCLAIMER • Navigate your cancer treatment The information and services provided by Fight Colorectal Cancer are for • Gather information for treatment general informational purposes only and are not intended to be substitutes for • Manage symptoms professional medical advice, diagnoses, • Find resources for personal or treatment. If you are ill, or suspect strength, organization and support that you are ill, see a doctor immediately. In an emergency, call 911 or go to • Manage details from diagnosis the nearest emergency room. Fight to survivorship Colorectal Cancer never recommends or endorses any specific physicians, products, or treatments for any condition. FIGHT COLORECTAL CANCER LOOK FOR THE ICONS We FIGHT to cure colorectal cancer and serve as relentless champions of hope Tips and Tricks for all affected by this disease through informed patient support, impactful policy change, and breakthrough Additional Resources -

External Link Teacher Pack

Episode 32 Questions for discussion 13th November 2018 US Midterm Elections 1. Briefly summarise the BTN US Midterm Elections story. 2. What are the midterm elections? 3. How many seats are in the House of Representatives? 4. How many of these seats went up for re-election? 5. What are the names of the major political parties in the US? 6. What words would you use to describe their campaigns? 7. The midterm elections can decide which party has the power in ____________. 8. Before the midterms President Trump had control over both the houses. True or false? 9. About how many people vote in the US President elections? a. 15% b. 55% c. 90% 10. What do you understand more clearly since watching the BTN story? Write a message about the story and post it in the comments section on the story page. WWF Living Planet Report 1. In pairs, discuss the WWF Living Planet Report story and record the main points of the discussion. 2. Why are scientists calling the period since the mid-1900s The Great Acceleration? 3. What is happening to biodiversity? 4. Biodiversity includes… a. Plants b. Animals c. Bacteria d. All of the above 5. What percentage of the planet’s animals have been lost over the last 40 years? 6. What do humans depend on healthy ecosystems for? 7. What organisation released the report? 8. What does the report say we need to do to help the situation? 9. How did this story make you feel? 10. What did you learn watching the BTN story? Check out the WWF Living Planet Report resource on the Teachers page. -

A Fair Share for Australian Manufacturing: Manufacturing Renewal for the Post-COVID Economy

A Fair Share for Australian Manufacturing: Manufacturing Renewal for the Post-COVID Economy By Dr. Jim Stanford The Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute July 2020 A Fair Share for Australian Manufacturing 1 About The Australia Institute About the Centre for Future Work The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think The Centre for Future Work is a research centre, housed within tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from the Australia Institute, to conduct and publish progressive philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned economic research on work, employment, and labour markets. research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or It serves as a unique centre of excellence on the economic candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried issues facing working people: including the future of jobs, out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, wages and income distribution, skills and training, sector and social and environmental issues. industry policies, globalisation, the role of government, public services, and more. The Centre also develops timely and Our Philosophy practical policy proposals to help make the world of work As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our better for working people and their families. society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are www.futurework.org.au more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite About the Author heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently Jim Stanford is Economist and Director of the Centre for Future needed. -

Weather and Climate

The Evolution of the T2L Science Curriculum Over the last four years, the Teach to Learn program created 20 NGSS-aligned science units in grades K-5 during our summer sessions. True to our plan, we piloted the units in North Adams Public Schools, and asked and received feedback from our science fellows and our participating teachers. This feedback served as a starting point for our revisions of the units. During year 2 (Summer of 2015), we revised units from year 1 (Summer/Fall 2014) and created new units to pilot. In year 3, we revised units from years 1 and 2 and created new units of curricula, using the same model for year 4. Our understanding of how to create rich and robust science curriculum grew, so by the summer of 2018, our final summer of curriculum development, we had created five exemplar units and established an exemplar unit template which is available in the T2L Toolkit. We made a concerted effort to upgrade all the existing units with exemplar components. We were able to do much, but not all. So, as you explore different units, you will notice that some contain all elements of our exemplar units, while others contain only some. The fully realized exemplar units are noted on the cover page. We did revise all 20 units and brought them to a baseline of “exemplar” by including the Lessons-At-A-Glance and Science Talk elements. Grade 3 Weather and Climate T2L Curriculum Unit Weather and Climate Earth and Space Science/Grade 3 In this unit, students will learn about the importance of our sun, how the earth moves in relationship to the sun, why different places on the earth are impacted differently by the sun, the concept of energy as it relates to heat and light, and the importance of energy exchange between the Earth and the sun. -

The Human Planet

INTRODUCTION: THE HUMAN PLANET our and a half billion years ago, out of the dirty halo of cosmic dust left over from the creation of our sun, a spinning clump of minerals F coalesced. Earth was born, the third rock from the sun. Soon after, a big rock crashed into our planet, shaving a huge chunk off, forming the moon and knocking our world on to a tilted axis. The tilt gave us seasons and currents and the moon brought ocean tides. These helped provide the conditions for life, which first emerged some 4 billion years ago. Over the next 3.5 billion years, the planet swung in and out of extreme glaciations. When the last of these ended, there was an explosion of complex multicellular life forms. The rest is history, tattooed into the planet’s skin in three-dimensional fossil portraits of fantastical creatures, such as long-necked dinosaurs and lizard birds, huge insects and alien fish. The emergence of life on Earth fundamentally changed the physics of the planet.1 Plants sped up the slow 1 429HH_tx.indd 1 17/09/2014 08:22 ADVENTURES IN THE ANTHROPOCENE breakdown of rocks with their roots, helping erode channels down which rainfall coursed, creating rivers. Photosynthesis transformed the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans, imbued the Earth system with chemical energy, and altered the global climate. Animals ate the plants, modifying again the Earth’s chemistry. In return, the physical planet dictated the biology of Earth. Life evolves in response to geological, physical and chemical conditions. In the past 500 million years, there have been five mass extinctions triggered by supervolcanic erup- tions, asteroid impacts and other enormous planetary events that dramatically altered the climate.2 After each of these, the survivors regrouped, proliferated and evolved. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

The Education of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 Race Relations and Community Development: The ducE ation of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960. Donald E. Devore Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Devore, Donald E., "Race Relations and Community Development: The ducaE tion of Blacks in New Orleans, 1862-1960." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4839. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4839 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

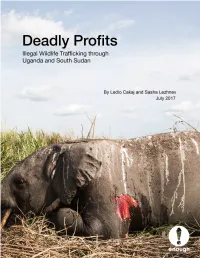

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

White Racial Identity and Anti-Racist Education: a Catalyst for Change by Sandra M

White Racial Identity and Anti-Racist Education: A Catalyst for Change by Sandra M. Lawrence and Beverly Daniel Tatum Although race and race- results. While some findings reveal related issues permeate and that White teachers have more influence every social institution, positive feelings about people of any White teachers currently color after participating in teaching in schools have had little multicultural courses and programs exposure to a type (Bennet, Niggle & of education in For Whites, the process Stage, 1990; Larke, which the impact involves becoming aware of Wiseman & Bradley, of race on one’s “whiteness,” accepting 1990), it seems that classroom practice this aspect of one’s identity as few of these and student socially meaningful and programs have had development was personally salient, and the ability to systematically ultimately internalizing a influence either examined (Sleeter, realistically positive view of prospective or 1992; Zeichner, whiteness which is not based current teachers' 1993). Some on assumed superiority. views about teacher education themselves as racial programs have responded to this beings or to alter existing teaching disparity by providing teacher practices (McDiarmid & Price, education students with courses 1993; Sleeter, 1992). dealing with multicultural issues as Even though the number of well as with experiences in diverse studies that point to successful classroom settings. Similarly, multicultural and anti-racist some school districts have courses continues to be low, we provided school faculty with believed that what we were doing multicultural professional in our courses with our students development workshops and was more successful than what we programs. Despite these pre- and had read about in formal studies. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring.