Detention Operations in Iraq: a View from the Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ncos Stepping up to Lead - Page 14 COMMENTARY Thoughts for the New Year – Today by Col

C M Y K Vol. 36, No. 06 Friday, February 6, 2009 NCOs stepping up to lead - page 14 COMMENTARY Thoughts for the New Year – today by Col. William Francis deep breath and said that he had to get back 6th Mission Support Group Commander to his load as he had a ways to go before he could stop for the day. He bent down picked The other day I saw a man pulling a trail- up the trailer and strained off into the dis- er fully loaded down the slow lane of Dale tance. As I watched him slowly fade from Mabry, he was struggling mightily against sight I wondered how long it would take an unbelievable load and so I pulled over him to get where he was going and why he and approached him. As I got close, he was did not just stop, put the trailer down and breathing hard, sweat dripping from his face, leave his burdens right there on the side of his clothes drenched with sweat and I asked the road. And then I realized that I have to him if he needed help, if he was OK. He fight not to do the same thing, I do not actu- said, he was fine, that he did not need any ally pull around a heavily loaded old trailer help and in fact that he did this everyday (and thankfully there is not a man pulling throughout the year. At this point he pulled a trailer everyday down Dale Mabry) but I the trailer off of the road out of traffic, wiped will cling to things that slow me, that burden his brow and explained to me that when me, that discourage me if I am not careful. -

Design Resketched with Staff Change

Help for those Weather. Increasing cloudiness with ~ who starve low tonight o•c, See page 9 htgh tomorrow 13° . '---------"' f'rldl;y, Aprll 29, 1983 Volume 74 1-44 News Briefs Design resketched Students protest with staff change (UPI) In Pans yesterday, thousands of By MICHELLE WING The design department was ac students took to the streets to protest a News Editor credited by the National Associa proposed law that would make it easier The resignation of all three design tion of Schools of Art and Design to get into ehte academic institutions. professors is the signal for major (NASAD). On the last visit, NASAD Marches and rallies also occurred in 11 renovation in the art department. asked that action be taken in the other French cities. Assistant Professor of Art Joy areas of salaries and contact hours. Wulke, Professor of Environmental " I don't see any problems meet Stone nominated Design Jane Van Alstyne and As ing those. They aren't the kind of sociate Professor of Art Jill Mitchell things that we can't solve," said (UPI) Former Senator Richard Stone are teaching for their last quarter. Helzer If these were not taken care was nominated by President Reagan r-- -1 .. · - -t Although resigning for different rea of satisfactorily. the schOol would yesterday to set up the Central Ameri sons, their absence presents a uni be placed on probation. can policy framework that Reagan out l •~(· <'-<t ~""{'\. que opportunity to the department. Wulke gave notice of her resigna .JU\c4 ..... f\~· lined Wednesday 1n his speech to a joint Acting Director of Art Richard tion in January 1983. -

KNOWN BURN PIT LOCATIONS: • Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq • Camp Adder, Talil AFB, Iraq • Al Asad Air Base, Kuwait • Ali Air B

KNOWN BURN PIT LOCATIONS: Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq Camp Adder, Talil AFB, Iraq Al Asad Air Base, Kuwait Ali Air Base (formerly Tallil Air Base) Al Quo, Iraq Al-Sahra, Iraq aka Speicher Camp Al Taji, IQ (Army Airfield) Al Taqaddum, Iraq (Ridgeway) Camp Anaconda, Iraq Camp Anderson, Iraq FOB Andrea Camp Arifjan, Kuwait(Camden Yards) Camp Ar Ramadi, Iraq Baghdad International Airport (BIAP), Iraq Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan Balad Air Force Base, Iraq Baquba, Iraq (See Warhorse) Camp Bastion Airfield, Afghanistan Camp Bucca, Iraq FOB Caldwell, Kirkush, Iraq Camp Cedar I and I, Talil AFB, Iraq Camp Chesty, Iraq Camp Courage, Mosul, Iraq Camp Cropper, Iraq Camp Delta, Al Kut, Iraq FOB Delta, Al Kut, Iraq Diwaniya, Iraq Djibouti, Iraq Camp Echo, Diwaynia, Iraq FOB Endurance - Qayyarah Airfield West/Saddam Air Base Falluja, Iraq FOB Fenty, Jalalabad, Afghanistan FOB Hammer a/k/a Butler Range FOB Freedom, Kirkuk, Iraq FOB Gabe, Baqubah, Iraq Former FOB Gains Mills Camp Geiger, Iraq Green Zone, Iraq Jalalabad, Afghanistan Kabul, Afghanistan Kalsu, Iraq Kandahar, Afghanistan Kirkuk, Iraq Kut Al Hayy Airbase, Iraq Camp Liberty, Iraq (aka Camp Trashcan) Camp Loyalty, Iraq FOB Marez, Mosul, Iraq FOB McHenry COB Meade, Camp Liberty, Iraq Mosul, Iraq Navstar, Iraq Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait Quatar, Iraq Q-West, Iraq - Qayyarah Airfield West/Saddam Air Base Camp Ridgeway, Iraq (Al Taquaddum) Camp Rustamiyah, Iraq Camp Salerno, Afghanistan Camp Scania, Iraq Scania, Iraq Camp Shield, Baghdad, Iraq COB Speicher, Iraq aka Al Sahra Airfield (formerly FOB) Camp Stryker, Iraq FOB Sykes, Iraq (Tall' Afar) Taji, Iraq Tall' Afar, Iraq Tallil AFB, Iraq (now is Ali Air Base) Camp Victory, Iraq FOB Warhorse, Baqubah, Iraq FOB Warrior, Kirkuk, Iraq . -

'Islamic State' (ISIS)

Issue 23, April 2018 Middle East: The Origins of the ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS) Mediel HOVE Abstract. This article examines the origins of the ‘Islamic State’ or the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham or Levant (ISIS) in light of the contemporary political and security challenges posed by its diffusion of Islamic radicalism. The Arab Spring in 2011 ignited instability in Syria providing an operational base for the terrorist group to pursue its once abandoned Islamic state idea. Its growth and expansion has hitherto proved to be a threat not only to the Middle East but to international security given its thrust on world domination. It concludes that the United States of America’s activities in the Middle East were largely responsible for the rise of the Islamic State. Keywords: Islamic state, Islamic radicalism, international security, Middle East. Introduction The goal of this article was to examine the origins of the “Islamic State” (IS) or the Islamic State of Iraq and Sham (Syria) (ISIS), the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in light of the contemporary political Mediel HOVE and security challenges posed by its diffu- Research Associate, sion of Islamic radicalism in a drive to estab- International Centre for Nonviolence, lish the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. This Durban University of Technology, is important given the fact that the roots of Durban, South Africa, and ISIS are under-examined in academic litera- Senior Lecturer, ture although they are tangentially covered History Department, University of Zimbabwe in the media. This study augments those E-mail: [email protected] studies that have attempted to examine the roots of ISIS such as Gulmohamad (2014). -

Camp Bucca Newletter #2

CAMP BUCCA NEWSLETTER VOLUME 1 EDITION 1 18 February 2008 Airmen Deliver School Supplies, Soccerballs to Safwan School Story and photo by SPC Brandon Hubbard Students received a gift of supplies and athletic equipment Wednesday, Feb. 6, at a school near Umm Qasr, Iraq. Airmen from the 887th Expeditionary Security Forces Squadron, Moody Air Force Base, Georgia, delivered dozens of supplies to the students, including paper, coloring books, pencils, crayons and hand-sewn book bags, as well as a dozen soccer balls. Many of the materials were donations from Girl Scout Troop 76 from Cornwall, New York. The 887th ESFS is charged with the external security of Forward Operating Base Bucca, under the command of the 300th Military Police Brigade. “Taking a diversion from routine patrols lets us meet and interact with the local populous,” said Staff Sgt. Matt Hamblen, the patrol squad leader. Speaking with the headmaster of the school, Hamblen explained that the items were all provided by Americans who support the Iraqi people and want to see them succeed. In January, Al-Basra became the ninth province to be returned to the Iraqi Government. During this period, the Army, Navy and Air Force service members at Camp Bucca in the southern province are assisting the Iraqi population with healthcare, supplies and other humanitarian aid. Continued on page 7 Table of Contents 2………………………CG’s Column 3………...CSM & Chaplain Column 4……………………TOA Ceremony 5…………………….Security Forces 6…………………..Top Marine Visit 7…………….Airmen Deliver (Con.) 8………………………….Bucca Cup 9…………………….Tell Your Story 10………………….Need A Passport 1 The Camp Bucca Newsletter is C OMMANDER COLUMN published in the interest of all Service- members, families and civilian employ- ees of the Camp Bucca, Iraq commu- Bucca Team, nity. -

ISIS: the Terrorist Group That Would Be a State

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CIWAG Case Studies 12-2015 ISIS: The Terrorist Group That Would Be a State Michael W.S. Ryan Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies Recommended Citation Ryan, Michael W.S., "IWS_02 - ISIS: The Terrorist Group That Would Be a State" (2015). CIWAG Irregular Warfare Studies. 2. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ciwag-case-studies/4/ This Book is brought to you for free and open access by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CIWAG Case Studies by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIWAG CIWAG IRREGULAR WARFARE STUDIES number 2 CENTER ON IRREGULAR WARFARE AND ARMED GROUPS I RREGULAR W ARFARE S TUDIES ISIS: The Terrorist Group That Would Be a State Michael W. S. Ryan number 2 U.S. Naval War College ISIS: The Terrorist Group That Would Be a State Irregular Warfare Studies In 2008, the U.S. Naval War College established the Center on Irregular Warfare and Armed Groups (CIWAG). The center’s primary mission is to bring together operators, practitioners, and scholars to share academic expertise and knowledge about and operational experience in violent and nonviolent irregular warfare chal- lenges, and to make this important research available to a wider community of interest. Our intent is also to include use of these materials within joint professional military educational (JPME) curricula to fulfill the needs of military practitioners preparing to meet the challenges of the post-9/11 world. -

A Pilot Study of Airborne Hazards and Other Toxic Exposures in Iraq War Veterans

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article A Pilot Study of Airborne Hazards and Other Toxic Exposures in Iraq War Veterans Chelsey Poisson 1,2,3 , Sheri Boucher 2,3,4, Domenique Selby 3,5,6, Sylvia P. Ross 2, Charulata Jindal 7, Jimmy T. Efird 8,* and Pollie Bith-Melander 9 1 Emergency Medicine, SMG Norwood Hospital, Norwood (Greater Boston Area), MA 02062, USA; [email protected] 2 School of Nursing, Rhode Island College, Providence, RI 02908, USA; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (S.P.R.) 3 HunterSeven Foundation, Providence, RI 02906, USA; [email protected] 4 Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Women and Infants Hospital, Providence, RI 02905, USA 5 Joint Trauma System, Defense Center of Excellence (CoE), Fort Sam Houston, Houston, TX 02905, USA 6 Emergency Medicine, Naval Medical Center San Diego (NMCSD), San Diego, CA 92134, USA 7 Faculty of Science, The University of Newcastle (UoN), Newcastle 2308, Australia; [email protected] 8 Cooperative Studies Program Epidemiology Center, Health Services Research and Development, DVAHCS (Duke University Affiliate), Durham, NC 27705, USA 9 Department of Social Work, California State University, Stanislaus, Stanislaus, CA 95382, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: Jimmy.efi[email protected]; Tel.: +1-650-248-8282 Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 7 May 2020; Published: 9 May 2020 Abstract: During their deployment to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), many Veterans were exposed to a wide array of toxic substances and psychologic stressors, most notably airborne/environmental pollutants from open burn pits. Service members do not deploy whilst unhealthy, but often they return with a multitude of acute and chronic symptoms, some of which only begin to manifest years after their deployment. -

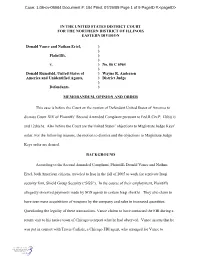

1:06-Cv-06964 Document #: 164 Filed: 07/29/09 Page 1 of 9 Pageid

Case: 1:06-cv-06964 Document #: 164 Filed: 07/29/09 Page 1 of 9 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION Donald Vance and Nathan Ertel, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) No. 06 C 6964 ) Donald Rumsfeld, United States of ) Wayne R. Andersen America and Unidentified Agents, ) District Judge ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM, OPINION AND ORDER This case is before the Court on the motion of Defendant United States of America to dismiss Count XIV of Plaintiffs’ Second Amended Complaint pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(1) and 12(b)(6). Also before the Court are the United States’ objections to Magistrate Judge Keys’ order. For the following reasons, the motion to dismiss and the objections to Magistrate Judge Keys order are denied. BACKGROUND According to the Second Amended Complaint, Plaintiffs Donald Vance and Nathan Ertel, both American citizens, traveled to Iraq in the fall of 2005 to work for a private Iraqi security firm, Shield Group Security (“SGS”). In the course of their employment, Plaintiffs allegedly observed payments made by SGS agents to certain Iraqi sheikhs. They also claim to have seen mass acquisitions of weapons by the company and sales in increased quantities. Questioning the legality of these transactions, Vance claims to have contacted the FBI during a return visit to his native town of Chicago to report what he had observed. Vance asserts that he was put in contact with Travis Carlisle, a Chicago FBI agent, who arranged for Vance to Case: 1:06-cv-06964 Document #: 164 Filed: 07/29/09 Page 2 of 9 PageID #:<pageID> continue to report suspicious activity at the SGS compound after his return to Iraq. -

Part I - Electrocution of Staff Sergeant Ryan D

INSPECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE 400 ARMY NAW DRIVE ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22202·4704 JUL 2 4 2009 MEMORANDUM FOR DEPUTY UNDER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR ACQUISITION AND TECHNOLOGY COMMANDER, U.S. CENTRAL COMMAND COMMANDER, MULTI-NATIONAL FORCES - IRAQ COMMANDER, ARMY SUSTAINMENT COMMAND DIRECTOR, DEFENSE CONTRACT MANAGEMENT AGENCY ARMY ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF FOR INSTALLATION MANAGEMENT SUBJECT: Review ofElectrocution Deaths in Iraq: Part I - Electrocution of Staff Sergeant Ryan D. Maseth, U.S. Army (Report No. IE-2009-006) We are providing this final report for review and COlUlnent. We considered luanagelnent COlnlnents to a draft ofthis repOli in preparing this final report. We requested and received nlanagenlent COlluuents from the COlumander, U.S. Central Conunand; Conl111ander, Multi National Forces - Iraq; C0l11111ander, Multi National Corps - Iraq; Director, Joint Staff; U.S. Anny Assistant Chief of Staff for Installation Managenlellt; and the Director, Defense Contract Managelllent Agency. We also received ll1anagement COl1unents fronl the COlnnlander, Al'111Y Materiel COllll11and, and the COll1l11ander, U.S. Ar1l1Y Crilllinal Investigation Conulland. All COn1l11ents confornled to the requirelllents of DoD Directive 7650.3, "Follow-up on General Accounting Office (GAO), DoD Inspector General (DoD IG), and Internal Audit Reports," June 3,2004. As a result of l11anagelllent COllllnents, we 111ade changes to recoll1111endatiol1s A.l.2, A.4, and B.4. The COllllnander, Multi National Corps - Iraq, disagreed with recol1Ullendation A.l.2. We request that the Comlnander, Multi National Corps - Iraq, reconsider his position and provide additional conllnents to this final report. A response by August 15, 2009, would be appreciated. Please provide COllunents that COnfOl'l11 to the requirelnents ofDoD Directive 7650.3. -

ACLU-RDI 867 P.1 AGO 0 0 0 7 2 5 DOD 000812

PRIVACY ACT STATEMENT AUTHORITY: Title 10 USC Section 301; Title 5 USC Section 2951; E.O. 9397 dated November 22, 1943 ISSN). PRINCIPAL PURPOSE: To provide commanders and law enforcement officials with means by which information may be accurately ROUTINE USES: Your social.securrty number is used as an additional/alternate means of identification to facilitate filing and retrieval. DISCLOSURE: Disclosure of your social security number is voluntary. ./6 4. 1. LOCATION ) 2 DATE IYYYYMMD 1.12ME6 1 FILE NUMBER Metro Park, Springfield, Virginia 2004/06/01 5. LAST NAME, FIRST NAME, MIDD AME 6. SSN 7. GRADE/STATUS LTC/O-5 ORGA1QfIA I iOWOR ADDRESS 115th Military Police Battalion, Salisbury, Maryland 9. , WANT TO MAKE THE FOLLOWING STATEMENT UNDER OATH: currently the Commander of the 115th Military Police (MP) Battalion (BN), Salisbury, MD, and was the Commander during the 115th deployment to Iraq. We mobilized for Operation Iraqi Freedom on 10 Feb 03 and arrived at our Mobilization Station at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, MD 16 Feb 03, and deployed via Kuwait arriving at Baghdad International Airport (BIAP) on or about 23 Apr 03. The 115th MP BN mission was to establish a 'Special Prison/Confinement Facility" (SP/CF) capable of holding 100 High Value Detainees (HVDs) in isolation at Camp Crupper on BIAP. We later assumed a second mission of running a Corps Holding Area as the 3rd MP BN was preparing to depart BIAP. With the exception of a two week period when•I was detailed to Abu Ghraib (AG), I remained at Camp Cropper until I departed for Kuwait in late Nov en route to the US. -

Interview with MAJ Mark Holzer

UNCLASSIFIED A project of the Combat Studies Institute, the Operational Leadership Experiences interview collection archives firsthand, multi-service accounts from military personnel who planned, participated in and supported operations in the Global War on Terrorism. Interview with LTC Wayne Sylvester Combat Studies Institute Fort Leavenworth, Kansas UNCLASSIFIED Abstract In charge of the 439th Military Police Detachment and deployed in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM from November 2003 to January 2005, Army Reserve LTC Wayne Sylvester, while in country, ran the Baghdad-area detention facility known as Camp Cropper. In this capacity, he was responsible for all the former top Iraqi regime officials in U.S. custody, the so-called Deck of 55 people that included Chemical Ali, Tariq Aziz, Doctor Germ, as well as Saddam Hussein himself. The principal challenge with guarding such High-Value Detainees, Sylvester said, was the “non-doctrinal nature of it.” Army doctrine, he observed, “does not adequately cover what you do with former regime members when you go into a country. Because of that, there were a lot of unique tasks and requirements.” Special security measures, accommodating interrogators and other agencies that needed access to detainees, dealing with the International Committee of the Red Cross and with prisoner complaints and protests were but some of these. In this interview, Sylvester also discusses the prisoner abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib Prison, what he feels went wrong, and what measures he took to ensure that Camp Cropper remained a model detention facility. “There is no question in my mind,” he said, “that the adversary can’t hold a candle to us over there.” What’s paramount, though, is “the information side of things and our ability to present our side of the picture so that it’s believable to the people we’re trying to help.” Turabian: Sylvester, Lieutenant Colonel Wayne. -

Switching Sides: Political Power, Alignment, and Alliances in Post-Saddam Iraq

SWITCHING SIDES: POLITICAL POWER, ALIGNMENT, AND ALLIANCES IN POST-SADDAM IRAQ by Diane L. Maye A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science Committee: _________________________________________ Mark N. Katz, Chair _________________________________________ Colin Dueck _________________________________________ T. Aric Thrall _________________________________________ Ming Wan, Program Director _________________________________________ Mark J. Rozell, Dean Date: ____________________________________ Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Switching Sides: Political Power, Alignment, and Alliances in post-Saddam Iraq A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University. by Diane L. Maye Master of Arts Naval Postgraduate School, 2006 Bachelor of Science United States Air Force Academy, 2001 Director: Mark N. Katz, Professor School of Policy, Government, and International Affairs Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2015 Diane L. Maye All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful husband, without whose love and support this dissertation would have not been completed. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge those who assisted me throughout my doctoral studies over the years. I would first like to acknowledge my chairman, Dr. Mark N. Katz, for agreeing to serve as my advisor and mentor during this process. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Colin Dueck, and Dr. T. Aric Thrall for serving as committee members. A very special thanks to my dear friend Sa’ad Ghaffoori for our countless meetings, emails, and conversations. I would also like to thank Governor Ahmed al Dulaymi, Thamir Hamdani, Waleed Mashhadani, Colonel Dale Kuehl, Colonel William Wyman, Colonel Richard Welch, Colonel Simon Gardner, as well as, Michael Pregent, Michael Sweeney, Paul D.