The Idea of a John Barrymore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

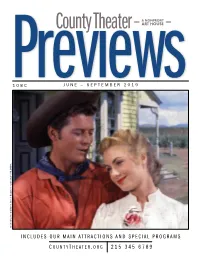

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Chapters 1-10 Notes

Notes and Sources Chapter 1 1. Carol Steinbeck - see Dramatis Personae. 2. Little Bit of Sweden on Sunset Boulevard - the restaurant where Gwyn and John went on their first date. 3. Black Marigolds - a thousand year’s old love poem (in translation) written by Kasmiri poet Bilhana Kavi. 4. Robert Louis Stevenson - Scottish novelist, most famous for Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stevenson met with one of the Wagner family on his travels. He died aged 44 in Samoa. 5. Synge – probably the Irish poet and playwright. 6. Matt Dennis - band leader, pianist and musical arranger, who wrote the music for Let’s Get Away From It All, recorded by Frank Sinatra, and others. 7. Dr Paul de Kruif - an American micro-biologist and author who helped American writer Sinclair Lewis with the novel Arrowsmith, which won a Pulitzer Prize. 8. Ed Ricketts - see Dramatis Personae. 9. The San Francisco State Fair - this was the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 and 1940, held to celebrate the city’s two newly built bridges – The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and The Golden Gate Bridge. It ran from February to October 1939, and part of 1940. At the State Fair, early experiments were being made with television and radio; Steinbeck heard Gwyn singing on the radio and called her, some months after their initial meeting. Chapter 2 1. Forgotten Village - a screenplay written by John Steinbeck and released in 1941. Narrated by Burgess Meredith - see Dramatis Personae. The New York authorities banned it, due to the portrayal of childbirth and breast feeding. -

FILMS by LAWRENCE JORDAN Lawrence Jordan in Person

Bay Area Roots, Risk & Revision FILMS BY LAWRENCE JORDAN Lawrence Jordan In Person Sunday, May 13, 2007 — 7:30 pm — Yerba Buena Center for the Arts I don’t know about alchemy academically, but I am a practicing alchemist in my own way. —Lawrence Jordan Lawrence Jordan has been making films since 1952. He is most widely known for his animated collage films, which Jonas Mekas has described as, “among the most beautiful short films made today. They are surrounded with love and poetry. His content is subtle, his technique is perfect, his personal style unmistakable.” Tonight’s screening sketches out a sampler of Jordan’s films, starting with Trumpit, a 1950s ‘psychodrama’ starring Stan Brakhage, with sound by Christopher Maclaine; Pink Swine, an anti-art dada collage film set to an early Beatles track; Waterlight the first of Jordan’s “personal/poetic documentaries” made in the 1950s aboard a merchant marine freighter during his days as a wandering flâneur; and Winterlight, a visual poem of the Sonoma County winter landscape. Lawrence Jordan’s four most recent films will conclude the night: Enid’s Idyll, Chateau/Poyet, Poet’s Dream, and Blue Skies Beyond the Looking Glass. (Jenn Blaylock) Trumpit (1956) 16mm, b&w, sound, 6 minutes, print from the maker Stan Brakhage stars as the constricted love in this spoof of pseudo-erotic card play. (LUX) Waterlight (1957) 16mm, color, sound, 7 minutes, print from the maker Among the wanderings that began in the 1950s was the filmmaker's 3-year stint in the merchant marine. Waterlight is a night and day impression of the never-constant, ever-changing vast ocean and its companion the sky. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

BIG BANDLEADERS’ PRIMARY INSTRUMENT TRIVIA QUIZ NEWSLETTER ★ LETTERS to the EDITOR About STUDIO ORCHESTRAS, SPIKE JONES, HERB JEFFRIES, and Others

IN THIS ISSUE: i f An interview with PEGGY LEE Reviews of BOOKS AND BIG RECORDS to consider about GEORGE WEIN, CRAIG RAYMOND, BAND KAY KYSER and others JUMP ★ A BIG BANDLEADERS’ PRIMARY INSTRUMENT TRIVIA QUIZ NEWSLETTER ★ LETTERS TO THE EDITOR about STUDIO ORCHESTRAS, SPIKE JONES, HERB JEFFRIES, and others BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER FIRST-CLASS MAIL Box 52252 U.S. POSTAGE Atlanta, GA 30355 PAID Atlanta, GA Permit No. 2022 BIG BAND JIMP N EWSLETTER VOLUME LXXXVII_____________________________BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER JULY-AUGUST 2003 lems than most of us experience. Later in life she took PEGGY LEE INTERVIEW engagements while requiring respirator treatments four times a day during ten years of her life. She played sold- out clubs with dangerously-high temperatures when she had to be carried off the stage to a hospital. She underwent open-heart surgery and suffered failing eye sight and a serious fall but continued to perform sitting in a chair until a few years before her death on January 21,2002 The Scene Veteran broadcaster and Big Band expert Fred Hall conducted the interview at Peggy Lee ’ s Bel Air home in the 1970s, at a time when she was still performing and still making records. The first question was about how her job with Goodman came about. BBJ: Did you j oin the Goodman band directly from singing in clubs? The cheerful Lee PL: Yes, I was singing in a club at that time I met him. Before that I had been singing on a radio The Background station in Fargo, North Dakota. -

Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames

Online Course: Film Noir - Danger, Darkness and Dames WRITTEN BY CHRIS GARCIA Welcome to Film Noir: Danger, Darkness and Dames! This online course was written by Chris Garcia, an Austin American-Statesman Film Critic. The course was originally offered through Barnes & Noble's online education program and is now available on The Midnight Palace with permission. There are a few ways to get the most out of this class. We certainly recommend registering on our message boards if you aren't currently a member. This will allow you to discuss Film Noir with the other members; we have a category specifically dedicated to noir. Secondly, we also recommend that you purchase the following books. They will serve as a companion to the knowledge offered in this course. You can click each cover to purchase directly. Both of these books are very well written and provide incredible insight in to Film Noir, its many faces, themes and undertones. This course is structured in a way that makes it easy for students to follow along and pick up where they leave off. There are a total of FIVE lessons. Each lesson contains lectures, summaries and an assignment. Note: this course is not graded. The sole purpose is to give students a greater understanding of Dark City, or, Film Noir to the novice gumshoe. Having said that, the assignments are optional but highly recommended. The most important thing is to have fun! Enjoy the course! Jump to a Lesson: Lesson 1, Lesson 2, Lesson 3, Lesson 4, Lesson 5 Lesson 1: The Seeds of Film Noir, and What Noir Means Social and artistic developments forged a new genre. -

Soco News 2018 09 V1

Institute of Amateur Cinematographers News and Views From Around The Region Nov - Dec 2018 Solent & Weymouth Anne Vincent has stepped down from Feel free to contact myself or other Laurie Joyce the position of the Southern Counties members of our committee. Region Chairman due to poor health but The new committee contacts are on will remain as a Honorary Member of the the last page of this magazine. Committee along with Phil Marshman who It brings me to say to you all in the also becomes an Honorary Member of the Region and further away A Very Happy Committee. Alan Christmas and a Happy New Year to you Wallbank I have been asked to stand as and your family Chairman which I duly accept and, along David Martin with my fellow Committee members, will help our region rise to the challenges of [email protected] Ian Simpson today! Frome Hello and welcome to another edition I have been a judge many times and Masha & of SoCo News. never had this hard a decision to make. Dasha The results of two competitions are Eventually, we placed Solent’s drama featured in this edition. There are a few “Someone To Watch Over Me” in second films that seem to be topping many of the place. This is a very well crafted Drama competitions. with exceptionally high standard of SoCo Comp It’s hardly surprising really, as they cinematography and direction. The main Results have been produced to a very high characters were well acted; to a standard standard. rarely seen in non professional films. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Glee Club Sings for Air Force

Madison College Library Harriaoaburg, Virginia 'HE BREEZE &» 1*R2*v Vol. xxxn Madison College, Harrisonburg, Virginia, Friday, March 23, 1956 No. 18 GLEE CLUB SINGS FOR AIR FORCE Paul Wenger New '56-57 President Choral Group Leaves On Tour, Of Men's Student Body Organization Newly elected Paul Wenger will Traveling To Iceland, Bermuda serve as president of men's student government organization for the '56-57 Thirty members of the Madison College Glee Club have been selected and left Thursday morn- session. ing, to fly to Bermuda, Iceland, and the Azores in an Easter Concert Tour with the Military Air Since *his transfer from Syracuse Transport Service Division of the United States Air Fcrce. Members were selected on a seniority University in his freshman year, Paul basis from the larger. sixty-voice Glee Club. has served on men's student govern- The Madison Choral group will be flown first to Iceland for personal appearances at air ment organization and was corres- bases, civic centers, and for several television shows. They will return to the United States for a ponding secretary last year. Further change of luggage and will then be flown to the warmer climates of Bermuda and the Azores. activities include FBLA, Sigma Delta Their music will represent a wide Rho fraternity, and YMCA cabinet. range of styles, and will include many With his business administration religious selections appropriate to the major he has a social science minor. Easter Season. Vice president elect is Eldon Pad- gett; recording secretary, Eddie Broy- The Glee Club, under the direction les; corresponding secretary, Roland of Miss Edna T.