Paul Klee Legends of the Sign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

Consummate Coach Tim Murphy’S Formidable Game S:7”

Daniel Aaron • Max Beckmann’s Modernity • Sexual Assault November-December 2015 • $4.95 Consummate Coach Tim Murphy’s formidable game S:7” Invest In What Lasts How do you pass down what you’ve spent your life building up? A Morgan Stanley Financial Advisor can help you create a legacy plan based on the values you live by. So future generations can benefit from not just your money, but also your example. Let’s have that conversation. morganstanley.com/legacy S:9.25” © 2015 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 1134840 04/15 151112_MorganStanley_Ivy.indd 1 9/21/15 1:59 PM NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2015 VOLUME 118, NUMBER 2 FEATURES 35 Murphy Time | by Dick Friedman The recruiter, tactician, and educator who has become one of the best coaches in football 44 Making Modernity | by Joseph Koerner On the meanings and history of Max Beckmann’s iconic self-portrait p. 33 48 Vita: Joseph T. Walker | by Thomas W. Walker Brief life of a scientific sleuth: 1908-1952 50 Chronicler of Two Americas | by Christoph Irmscher An appreciation of Daniel Aaron, with excerpts from his new Commonplace Book JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 41.37. 41.37. R 17 Smith Campus Center under wraps, disturbing sexual-assault ULL IMAGE F findings, a law professor plumbs social problems, the campaign OR F NIVERSITY crosses $6 billion, cutting class for Christmas, lesser gains U and new directions for the endowment, fall themes and a SSOCIATION FUND, B A ARVARD H brain-drain of economists, Allston science complex, the Under- USEUM, RARY, RARY, B M graduate on newfangled reading, early-season football, and I L a three-point shooter recovers her stroke after surgery DETAIL, PLEASE 44 SEE PAGE EISINGER R OUGHTON H p. -

Paul Klee First, Let’S Learn to Say His Name: Klee Is Pronounced Similar to the Word Clay

Name _____________________________________ Homeroom Teacher _________________________ Behind the Masterpieces A look at the life and work of the artists behind famous artworks Paul Klee First, let’s learn to say his name: Klee is pronounced similar to the word clay. Try it a few times! Senecio, 1922 Red Bridge, 1928 Castle and Sun, 1928 Becoming an artist Paul Klee was born in Switzerland in 1879. Both of his parents were musicians and he loved music so much he thought he might become a musician too. He learned to play the violin but after creating drawings with sidewalk chalk his grandmother gave him he realized he liked drawing even more and decided to study art to become an artist! When Paul Klee first created art he didn’t use any color because he thought his art didn’t need it. Eventually he discovered how wonderful color was and started creating beautiful, colorful, paintings. Art Movement and Style: Taking a closer look h Take a minute and look at the three artworks above painted by Paul Klee. Paul Klee made many artworks where his subject matter (what he painted) was made out of geometric shapes. The subject in the first painting is a portrait (picture of a person). The last painting has a castle as the subject. Take a close look at the painting in the middle. Besides a bridge what do you think the subject is in the middle painting? __________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ These paintings of Paul Klee’s are known as cubism. We’ve already studied another artist who created cubist artwork using mostly squares and rectangles. -

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD • Woven into regular elementary classes – integration • Instructional Assistants specializing in art – taught within rotation • Parents/Volunteers – usually after school • Art Clubs sponsored by elementary teachers – usually after school • Certified Art Teachers (2) – Castle Hills Elementary & Montgomery Elementary ELEMENTARY LESSON DESIGNS • NEISD Visual Art Webpage (must be logged in) https://www.neisd.net/Page/687 to find it open NEISD website > Departments > Fine Arts > Visual Art on left • Curriculum Available K-5 • Elementary Art TEKS • Lesson Designs (listed by topic and grade level) SOURCES FOR LESSON DESIGNS • Pinterest https://www.pinterest.com/ • YouTube • Art to Remember https://arttoremember.com/lesson-plans/ • SAX/School Specialty (an art supply source) https://www.schoolspecialty.com/ideas- resources/lesson-plans#pageView:list • Blick Lesson Plans (an art supply source) https://www.dickblick.com/lesson-plans/ LESSON TODAY, GRADES K-1 • Gr K-1, “Kitty Cat with Her Bird” • Integrate with Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Book The Cat and the Bird by Geraldine Elschner & Peggy Nile and watch the “How To” video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tW6MmY4xPe8 • Artwork: Cat and Bird, 1928 LESSON TODAY, GRADES 2-3 • Gr 2-3, “Me, On Top of Colors” • Integrate with Social Studies with Personal Identity, Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Poem Be Glad Your Nose Is On Your Face by Jack -

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

Paul Klee and the Decorative in Modern Art

P1: IML/FFX P2: IML/FFX QC: IML/FFX T1: IML CB560-FM CB560-Anger-v6 July 16, 2003 9:51 PAUL KLEE AND THE DECORATIVE IN MODERN ART q Jenny Anger Grinnell College iii P1: IML/FFX P2: IML/FFX QC: IML/FFX T1: IML CB560-FM CB560-Anger-v6 July 16, 2003 9:51 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Jenny Anger 2004 Thisbook isin copyright. Subject to statutoryexception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Janson Text 10/13 pt. and Gill Sans System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anger, Jenny, 1965- Paul Klee and the decorative in modern art / Jenny Anger. p. cm. Includesbibliographical referencesand index. isbn 0-521-82250-5 1. Klee, Paul, 1879–1940 — Aesthetics. 2. Matisse, Henri, 1869–1954 — Aesthetics. 3. Decoration and ornament — Philosophy. I. Title. N6888.K55A9 2003 760092 —dc21 2002041548 isbn 0 521 82250 5 hardback iv P1: -

Introduction to Music Instructor: Dr

Attendance/Reading Quiz! Mu 110: Introduction to Music Instructor: Dr. Alice Jones Queensborough Community College Sections C5A (Fridays 9:10-12) and F5A (12:10-3) Fall 2016 Recap • Creative freedom is not absolute • Skill, desire, taste of audience, economic factors, availability of resources, government control • Musicians make music in spite of and because of politics • Olivier Messaien, Dmitri Shostakovich • Not all art is made for the purposes of self-expression Follow-up questions • Why does an artist have to write music that pleases the government or rulers? • Patronage system • Catholic Church – Perotin, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina • Aristocracy and nobility – Jean-Baptiste Lully, Johann Sebastian Bach, Joseph Haydn • Totalitarian governments • USSR – Dmitri Shostakovich • America? • Un-American Activities Commission – publicly interrogating, berating, and punishing musicians who made un-American music Follow-up questions • How did government officials identify so-called rebellious music? • “[Music should resemble] symphonic sonorities or with the plain language of music that can be understood by all… [not] only appeal to aesthetes and formalists who have lost all healthy taste.” –Pravda, Jan. 28, 1936 • Description of what music “should” sound like is so vague that they are 1) difficult to obey; and 2) can be manipulated against any composer • I am unsure why musicians were sent to camps and what the Soviet government was proposing [The Great Terror or the Great Purge. Besides the musicians, why were others such as family members exiled? 1) Because they expressed ideas that the government did not like; 2) To punish people; 3) To instill fear so that other people would obey. -

Daniel Michael Zolli

Daniel Michael Zolli DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY • 240 BORLAND BUILDING THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY • UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 16802 email: [email protected] • cell: 617.594.5747 http://www.sites.psu.edu/zolli EDUCATION Ph.D., October 2016 Harvard University, History of Art & Architecture Department Dissertation: “Donatello’s Promiscuous Technique” Committee: Frank Fehrenbach, Joseph Koerner, Alina Payne A.M., 2011 Harvard University, History of Art & Architecture Department Qualifying Paper: “Emblems and Enmity in Correggio’s Camera di San Paolo” Research student in Art History, 2008 Ruprechts-Karls Universität, Heidelberg, Germany B.A., 2o07 Wesleyan University (CT), Art History Honors: Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, high distinction and prize for best thesis in art history major (on annotated copies of Aldus Manutius’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili) Coursework in Studio Art and Art History, 2002 Università degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy APPOINTMENT HISTORY Assistant Professor (tenure-track), 2017- The Pennsylvania State University, Department of Art History Affiliated Faculty: Center for Early Modern Studies; Arts & Design Research Incubator Residential Postdoctoral Fellow, 2016-17 Getty Research Institute Visiting Lecturer, 2014-15 Tufts University, Department of Art & Art History, Curatorial Assistant, 2008-9 Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Drawings & Prints RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Workshop practice; oral tradition and ethnohistory as art-historical methods; folklore, practical jokes, and the popular novella; trans-mediality; technical studies; media archaeology; conceptual and practical interfaces between art and law; Spanish colonialism; antiquarianism, forgery, and the misidentification of artists or subject matter, especially in southern Italy; physical decay in art; the plague and its impact on art; the nineteenth-century reception of Renaissance art. -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

LARRY A. SILVER Curriculum Vitae Born

LARRY A. SILVER Curriculum Vitae Born: 14 October 1947. U. S. Citizen. married, two children. UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION: University of Chicago, A. B., June 1969 Concentration: Art. Special Honors. General Honors GRADUATE EDUCATION Harvard University, Department of Fine Arts M. A., 1971; Ph. D., 1974 Dissertation: Quinten Massys (Director: Seymour Slive) ACADEMIC POSITIONS U. of California, Berkeley, 1974-1979 Lecturer in History of Art, 1974-1975 Assistant Professor of History of Art, 1975-1979 Northwestern University, 1979-1997 Associate Professor of Art History, 1979-1985 Professor of Art History, 1985-97 Chairman, Dept. of Art History, 1983-1986, 1997 Master, Chapin/Humanities Residential College, 1988-91, 1992-94, 1996-97 Martin J. and Patricia Koldyke Professor of Teaching Excellence, 1996-98 Smith College, Ruth and Clarence Kennedy Professor in the Renaissance, autumn 1994 Semester at Sea (University of Pittsburgh; University of Virginia; Colorado State) Fall 2001; Fall 2006; Summer 2008; Summer 2010; fall 2012; spring 2018 U. of Pennsylvania, 1997--2017 Farquhar Professor of the History of Art, emeritus 2017--present Chair of Graduate Group in History of Art, 1998-2000 Interim Chair, spring, 2005 Bogen Faculty Exchange Professor, The Hebrew University, fall 2007 Member, graduate group, German, 1999-- Member, graduate group, History, 2001— Director, University Scholars, 2010-17 President, Phi Beta Kappa, Delta Chapter, 2010-12 GRANTS and AWARDS: Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, 1969-1970 Danforth Graduate Fellowship, 1969-1974 Kress Foundation -

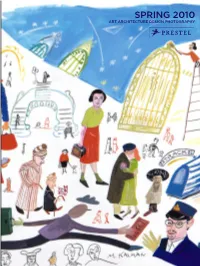

Englisch VS 1 10-7Er K.Qxd:PRESTEL VS

Maira Kalman, Next Stop, Grand Central , 1999 / © 2009 Maira Kalman PRESTEL HEAD OFFICE PRESTEL UK PRESTEL USA 978-3-7913-9845-7 ISBN-978-3-7913-9845-7 SPRING 2010 Prestel Verlag Prestel Publishing Ltd. Innovative Logistics Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH 4 Bloomsbury Place 575 Prospect Street ART ARCHITECTURE DESIGN PHOTOGRAPHY Königinstrasse 9 London WC1A 2QA Lakewood, NJ 08701 D-80539 Munich, Germany Tel: +44 (0)20 7323-5004 Tel: (888) 463-6110 Tel: +49 (0)89 242908300 Fax: +44 (0)20 7636-8004 Fax: (877) 372-8892 Fax: +49 (0)89 242908335 e-mail:[email protected] e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] EUROPE ASIA, AFRICA GERMANY Verlegerdienst München INDIA, NEPAL, Gutenbergstrasse 1 SRI LANKA, BHUTAN TBI - Publisher & Distributors D-82205 Gilching, Germany 1882 Bhasker Bhawan Tel: +49 (0)8105 388-123 Village Kotla, Mubarkpur Fax: +49 (0)8105 388-259 New Delhi 110003 / India e-mail: [email protected] Tel: 9811791246 / 01146056198 e-mail: [email protected] AUSTRIA Mohr Morawa Buchvertrieb Sulzengasse 2 SOUTHEAST ASIA Peter Couzens A-1230 Wien Sales East Tel: +43 (0)16 68 01 45 43 Soi Pichit Fax: +43 (0)16 68 96 800 Sukhumvit Road 18 e-mail: [email protected] Klong Toei Bangkok 10110 SWITZERLAND Buchzentrum Thailand Industriestr. Ost 10 Tel + Fax: +66 2258 1305 CH-4614 Hägendorf Mobile: +66 85058 6265 Tel: +41 (0)62 209 26 26 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 (0)62 209 26 27 e-mail: [email protected] CHINA, HONG KONG, KOREA, PHILIPPINES, Edward Summerson FRANCE Interart TAIWAN -

Autobiographical in the Oeuvre Of

CALIFORNIA STATE UNNERSITY, NORTHRIDGE LONGING FOR MAMAN: AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IMAGES IN THE OEUVRE OF LOUISE BOURGEOIS A the is . ubmitted jn partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Alts in Art Hi tory by Karen Jo Schifmao December 2003 DEDICATION For Norman and Jonathan lll ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It has been a privilege to learn and write about the work of Louise Bourgeois. I never would have embarked upon this task without the support of many people. First, I would like to acknowledge my mother, Gloria Derchan, who introduced me to the subject of art history back in 1973 when we both began taking classes at Los Angeles Valley College, and who also has instilled in me an appreciation for aesthetics. I thank my father, Harold Derchan, who always encouraged my educational endeavors and taught me to have perseverance and determination. I thank my brother, Randall Derchan, who so patiently assisted me with the desktop publishing of this document, and my sister, Patti Meiselman, who always supports me. I thank my fellow art history graduate students, colleagues, and professors at the university, who have served as mentors and supporters throughout these past years, most especially, Professor Trudi Abram, Nina Berson, Anna Meliksetian, and Rachel Pinto. I thank my thesis committee members for their help and guidance. Firstly, Professor Jean-Luc Bordeaux, who has taught me to recognize and focus on the formal qualities in art, and to keep my knowledge base in the fi eld as broad as possible. Special thanks go to Professor Kenon Breazeale who has served on my committee since its inception.