The Mineralogy and Fabric Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brickearth Soils in the South-East New Forest Are Well Drained

BRIGKEARTH, AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE CHARACTER OF SOILS, IN THE SOUTH-EAST NEW FOREST By G. C. FISHER I. INTRODUCTION BRICKEARTH is an indefinite geological term applied to loamy, superficial deposits of Quaternary age. Structureless deposits of brickearth are common in Southern and Eastern England and in most, particles in the size range iojxm to 200(j.m are dominant. The Geological Survey maps a number of patches of brickearth in the south western New Forest, most notably at Barton-on-Sea. Additional deposits of brickearth have been described from the New Forest (White 1915, Everard 1952, Lewin 1966a) and the author records several more in this paper for the south-east of the area. The first aim of the work here recorded was to determine the extent of brickearth deposits in the south-east corner of the New Forest. Everard (1952) provides a very general map of brickearth distribution around Southampton Water which shows a large deposit at Fawley not recorded by the Geological Survey. As well as adding to the map of Everard an attempt was made to locate shallow deposits of brickearth, not mappable by the geologist, but which may make an important contribution to soils. A further aim of the work was to try and determine the origin of the brickearth. Some brickearths have been described, especially from Kent (Pitcher et al 1954, Dines et al 1954), which have a particle size distribution which shows them to be true loesses, i.e. 50 per cent of the particles have diameters in the range 10 |un to 50 (im (Russell 1944, Pecsi 1968). -

Landscape Assessment of Kent 2004

CHILHAM: STOUR VALLEY Location map: CHILHAMCHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTION North of Bilting, the Stour Valley becomes increasingly enclosed. The rolling sides of the valley support large arable fields in the east, while sweeps of parkland belonging to Godmersham Park and Chilham Castle cover most of the western slopes. On either side of the valley, dense woodland dominate the skyline and a number of substantial shaws and plantations on the lower slopes reflect the importance of game cover in this area. On the valley bottom, the river is picked out in places by waterside alders and occasional willows. The railway line is obscured for much of its length by trees. STOUR VALLEY Chilham lies within the larger character area of the Stour Valley within the Kent Downs AONB. The Great Stour is the most easterly of the three rivers cutting through the Downs. Like the Darent and the Medway, it too provided an early access route into the heart of Kent and formed an ancient focus for settlement. Today the Stour Valley is highly valued for the quality of its landscape, especially by the considerable numbers of walkers who follow the Stour Valley Walk or the North Downs Way National Trail. Despite its proximity to both Canterbury and Ashford, the Stour Valley retains a strong rural identity. Enclosed by steep scarps on both sides, with dense woodlands on the upper slopes, the valley is dominated by intensively farmed arable fields interspersed by broad sweeps of mature parkland. Unusually, there are no electricity pylons cluttering the views across the valley. North of Bilting, the river flows through a narrow, pastoral floodplain, dotted with trees such as willow and alder and drained by small ditches. -

Medway Landscape Character Assessment March 2011

Medway Landscape Character Assessment March 2011 Contents Executive Summary ......................................................... iii Landscape Character Area summary sheets ...... 17 Landscape Character Areas ......................................... v Appendices ...................................................................... 113 Introduction .......................................................................... 1 A: Planning policy ............................................... 113 What is landscape and why it matters ................ 1 B: Landscape types ............................................. 118 Purpose and scope .................................................. 1 C: Methodology and analysis ........................... 122 Planning context ...................................................... 2 D: Sample survey sheets ................................... 124 Landscape Character Assessment – previous ....... E: Analysis mapping ............................................. 125 studies ....................................................................... 2 F: Common Terms .............................................. 131 Methodology and analysis ..................................... 3 Bibliography .................................................................... 133 Content and Structure ........................................... 4 Medway’s Landscape ........................................................ 7 Wider influences and considerations ................................ 7 New development and landscape -

Brit~Sh Brick Society

BRIT~SH BRICK SOCIETY T% ;~m NQ 41 Feb'87 OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY Chairman Mr T P Smith BA, MA, School Flat, Dartford Gramma. and M.Litt., MIFA School for Boys, West Hill Editor of Dartford, Kent DA1 2HW I Information' Hon. Sec Mr M Hammett ARIBA 9 Bailey Close, Lucas Road and High Wycombe, HP13 6QA Membership Sec (0494) 20299 (who also receives all direct subscriptions £3 p.a.) Enquiries Sec Mr 0 Kennett 27 Lords Lane, Bradwell Great Yarmouth Norfolk NR31 8NY (for enquiries on academic or historical matters) Hon. Treasurer Mr M 0 P Ha~mond A.B.I.A. T. St Annes' 13 Jackson Road, Parkstone Poole, Dorset BH12 3AJ (only mattersconcerning the annual ales, expenses etc.) Publications Mrs A Los "Peran", Plaxton Bridge, Officer and Woodmansey, Beverley Bibliographer E Yorks HU17 ORT OFFICERS OF THE BRICK SECTION OF THE BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Chairman Mr T W T Tatton-Brown BA 2 MillLane, St Radigunds Canterbury, Kent. Hon. Sec Mr M Hammett ARIBA (Address as above) Membership Sec Miss I B McClure 61 Old Park Ridings BAA Winchmore Hill London NZJ 2n Members oF the BAA may elect to join its Brick Section and, as such, will be eligible for affiliation to the British Brick Society. They should" inform the Hon Secretary of the BBS oF their address so that they can be included in the membership list. March 1987 BRITISH BRICK SOCI ETY RMATIO 4 CD EDITORIAL: BUILDING CERAMICS CO (j) or-- In 1986 the British Brick Society visiten sites in West Sussex and Surrey; this was the > first meeting of its kind -unconnected with ce the AGM and it is hoped that the exercise can be. -

A Conceptual Model for Loess in England

1 A Conceptual Model for Loess in England: Principles and Applications 2 3 Assadi-Langroudi, A 4 5 6 Arya Assadi-Langroudi 7 School of Architecture, Computing and Engineering, University of East London, London, United Kingdom 8 Email: [email protected] 9 10 11 Abstract 12 PTD, an acronym for Provenance - Transport - Deposition, is a multilayer geomorphotechnical system, the 13 combination of geomorphology, Quaternary Sciences, and geotechnical consequences of its 14 implementation in groundworks and other crosscutting disciplines. Embedded in its three layers are 15 geographical, geochemical, geophysical, mineralogy, dating, lithological and geotechnical inputs. In this 16 state-of-the-art review contribution and for Loess in England, Syngenetic and Epigenetic mechanisms are 17 drawn out and used to generate the three constitutive layers for three conceptual PTD models and the 18 interrelationships among them. The developed models are then deployed to inform earthworks design for 19 three HS2 embankments in Chiltern Hills. 20 21 22 Key words 23 Loess; Syngenetic; Epigenetic; Quaternary; Earthworks 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 1 1 1. Introduction 2 Patchily scattered loess successions in basins and valleys, on hills and around rivers over Southern England 3 were first reported in Prestwich (1863). Sequences of Loess across Midland, South and South East England 4 with greater than 1m thickness have significant hiatuses and are restricted to Thames Estuary in North Kent 5 (Catt, 1978). Loessic sequences of up to 8m thickness have been reported in South Essex across as area of 6 approximately 10Km in diameter and centred around Stambridge (Northmore et al., 1996), and sequences 7 of up to 4m thickness in subsurface buried erosional channels (Milodowski et al., 2015). -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POTS, POTTERS and POTTERIES, C.1200–1910 by MICHAEL FARLEY and BARBARA HURMAN Offprinted from RECORDS of BUCKS

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POTS, POTTERS AND POTTERIES, C.1200–1910 BY MICHAEL FARLEY AND BARBARA HURMAN Offprinted from RECORDS OF BUCKS Vol. 55 2015 BUCKINGHAMSHIRE POTS, POTTERS AND POTTERIES, c.1200–1910 MICHAEL FARLEY AND BARBARA HURMAN An attempt is made to list Buckinghamshire’s pottery production sites and potters from the thirteenth century until c.1910 and to give a short description of their products where known. The information is derived from confirmed kiln sites, from surface finds of ‘waster’ material which indicate production, and from a range of documentary sources including field names. There remains considerable scope for further local research; a number of suspected production sites have not yet been located on the ground and further local study would certainly identify other potters and link named potters to specific locations. Several features have emerged from the study. Firstly, a number of production sites are known to have been active in recent centuries, but for which there is no earlier record. It is suspected that some of these may have had earlier undocumented activity. Secondly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, many pottery centres were located on agriculturally marginal land. Thirdly, several of the pottery families followed their trade over generations and this is likely to have been the case long before documentation becomes available. Finally, the number of ‘pot hawkers’ recorded, particularly in the mid-nineteenth century, is surprising as it almost equals the number of working potters; their role in distributing the wares of country potteries may have been underestimated in the past. quently exposed, for example by being ploughed up, I NTRODUCT ION weathering of their relatively soft and open fabric Until shortly before the Roman conquest all pottery may leave little trace of them. -

Landscape SPD

Supplementary Planning Document Mole Valley Local Plan Landscape SPD July 2013 This document can be made available in large print, on audio cassette, in Braille and in other languages Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Policy Context 3 3 Using the Landscape SPD 5 4 The Landscape of Mole Valley - An Overview 11 5 Character Profiles 21 5.1 Thames Basin Lowlands 23 5.1.1 Character Profile: Esher and Epsom 24 5.1.2 Character Profile: Ockham and Clandon 26 5.1.3 Character Profile: Lower Mole 29 5.2 North Downs 31 5.2.1 Character Profile: Box Hill 33 5.2.2 Character Profile: Mole Gap 37 5.2.3 Character Profile: Ranmore and Hackhurst Downs 40 5.3 Wealden Greensand 42 5.3.1 Character Profile: Holmesdale 43 5.3.2 Character Profile: Pippbrook and Tillingbourne 46 5.3.3 Character Profile: Reigate Greensand 49 5.3.4 Character Profile: Leith Hill Greensand 51 5.4 Low Weald 54 5.4.1 Character Profile: Open Weald 55 5.4.2 Character Profile: Wooded Weald 57 6 Glossary and Sources of Further Information 61 1 Appendices 62 Mole Valley District Council Mole Valley Local Development Framework Landscape SDP Contents Mole Valley Local Development Framework Landscape SDP Mole Valley District Council 1 Introduction Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 The landscape of Mole Valley is cherished by its residents and visitors alike. Large extents are protected through European, National and local designations. Substantial areas are owned or managed by organisations whose focus is primarily conservation and informal recreation, such as the National Trust and the Surrey Wildlife Trust. -

Background Document

Draft West Sussex Joint Minerals Local Plan (Regulation 18) Background Document April 2016 Contents Contents ................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................... 2 Duty to Cooperate ................................................................................ 3 2. Vision and Objectives ........................................................................ 4 3. Minerals Supply and Demand .......................................................... 29 Aggregates – Land won sharp sand and gravel ....................................... 29 Aggregates – Soft sand ....................................................................... 37 Silica Sand ......................................................................................... 50 Chalk ................................................................................................ 60 Clay .................................................................................................. 70 Stone ................................................................................................ 85 Hydrocarbons (Oil and Gas) ................................................................. 93 4. Safeguarding Minerals Resource ................................................... 107 5. Safeguarding Minerals Infrastructure ........................................... 128 6. Glossary ....................................................................................... -

Archaeology Desk Based Assessment & Heritage Statement

WELSFORD STREET LONDON, SE1 5RA ARCHAEOLOGY DESK BASED ASSESSMENT & HERITAGE STATEMENT VOLUME 1: ARCHAEOLOGY Prepared for LB Southwark Mills Whipp Projects Ltd., 40, Bowling Green Lane, London EC1R 0NE 020 7415 7044 [email protected] December 2017 Executive Summary The purpose of the desk based assessment of archaeology is to identify the archaeological potential of the development site and summarise the impact of the proposed development on it. It has been prepared by Mills Whipp Projects. The site is centred on National Grid Reference TQ 3411 7858 and is approximately 0.21ha in area. During the preparation of this report the Greater London Historic Environment Record (HER) was consulted for an area of 500m radius centred on TQ 3411 7858 (Historic England report No. 137750) (Fig. 2). The chief cartographic sources have been used and a selection of these is appended as illustrations. This research shows that the subject site does not contain any Scheduled Ancient Monuments and does not lie within a Designated Archaeological Area as defined in Schedule Ancient Monuments & Archaeological Areas Act 1979. The site does not contain any listed buildings but does lie within in the Bermondsey Lake Archaeological Priority Zone (APZ). Under the provision of Saved Policy 3.19 a pre- determination evaluation of the site will be required. There are no known non- designated archaeological remains listed within Historic England’s Historic Environment Record on the site. During the prehistoric/Roman period the site is likely to have lain a few hundred metres north of the Bermondsey Lake. Ancient occupation would probably have focussed on the lake’s shoreline and Neolithic and Bronze Age peats and a platform have been recorded by the Old Kent Road. -

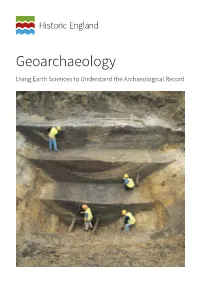

Geoarchaeology Using Earth Sciences to Understand the Archaeological Record Summary

Geoarchaeology Using Earth Sciences to Understand the Archaeological Record Summary This guidance document covers the use of geoarchaeology to assist in understanding the archaeological record. Geoarchaeological techniques may range in scale from landscape studies to microscopic analysis, and are carried out by practitioners with specialist knowledge about the physical environment in which archaeological stratigraphy is preserved, and excavations take place. The main aim is usually to understand site formation processes, but there may also be issues concerning site preservation, refining field interpretations of archaeological contexts and identifying changes in the physical landscape through time. Previous editions of this document were compiled in 2004 and 2007 by Gianna Ayala, Matthew Canti, Jen Heathcote, Raimonda Usai and Jane Siddell. This edition was revised in 2015 by Matthew Canti with help from Jane Corcoran. First published by English Heritage 2004 Revised and reprinted by English Heritage 2007 This edition published by Historic England December 2015 All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated HistoricEngland.org.uk/research/approaches/research-methods/archaeology/ geoarchaeology/ Front cover Section across the ditch of the south bailey at Norwich Castle. © Norwich Archaeological Unit Contents Introduction .........................................1 3 Project Organisation and Planning .............................43 1 Site Formation Processes 3.1 Planning and costs ....................................43 and Deposits -

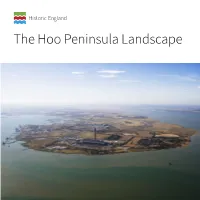

The Hoo Peninsula Landscape

The Hoo Peninsula Landscape The Hoo Peninsula Landscape The Hoo Peninsula Landscape Sarah Newsome, Edward Carpenter and Peter Kendall Published by Historic England, The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH www.HistoricEngland.org.uk Historic England is a Government service championing England’s heritage and giving expert, constructive advice, and the English Heritage Trust is a charity caring for the National Heritage Collection of more than 400 historic properties and their collections. © Historic England 2015 Images (except as otherwise shown) © Historic England, © Crown Copyright. HE, or Reproduced by permission of Historic England Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data (on Fig 2 and inside back cover) courtesy of the CGIAR Consortium for Spatial Information. First published 2015 ISBN 978-1-84802-225-6 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data Front Cover A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. View looking west across the Hoo Peninsula with the Grain industrial area in the foreground. All rights reserved [26477/050] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Inside front cover Control room at Kingsnorth Power Station. Application for the reproduction of images should be made to Historic England. Every effort has been made to [DP172037] trace the copyright holders and we apologise in advance for any unintentional omissions, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition of this book. Frontispiece Vessels moored in the Medway For more information about images from the Archive, contact Archives Services Team, Historic England, estuary off Port Victoria, Isle of The Engine House, Fire Fly Avenue, Swindon SN2 2EH; telephone (01793) 414600. -

The 3D Geology of London and the Thames Gateway: a Modern Approach to Geological Surveying and Its Relevance in the Urban Environment

The 3D geology of London and the Thames Gateway: a modern approach to geological surveying and its relevance in the urban environment J.R.Ford H.Burke K.R.Royse S.J.Mathers British Geological Survey, Nottingham, England ABSTRACT As a provider of geological advice to industry, academia and the public, the British Geological Survey (BGS) has recognised the need to change the way it presents geoscientific information, resulting in the construction of attributed 3D geological models. The need to deliver 3D modelling solutions is of great importance in urban areas, where geological factors play a major role in supporting ground investigations and sustainable water management studies. The 3D geological model of London and the Thames Gateway occupies an area of approximately 3200 km2 and extends to a depth of 150 m. It includes a total of 38 units, ranging from Artificial Deposits and Quaternary sediments down to Tertiary and Cretaceous bedrock. The model is built using existing geological surveys, DEMs and extensive borehole and site investigation data. Modelling was carried out using GSI3D (Geological Surveying and Investigation in 3 Dimensions) software. This software and its associated workflow produce a series of gridded volumes of the geological units, constrained at depth by a network of cross-sections constructed by the geologist. The Thames Gateway model was attributed by assigning property values to each geological unit. This has provided a way of visualising the spatial relationships between geological units with differing properties. The model has revealed previously unrecognised geological information. Further benefits of the attributed model include the ability to visualise and appreciate the link between lithology and physical characteristics.