Sumana R. Ghosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S*U*P*E*R Consciousness Through Meditation Douglas Baker B.A

S*U*P*E*R CONSCIOUSNESS THROUGH MEDITATION DOUGLAS BAKER B.A. M.R.C.S. L.R.C.P. You ask, how can we know the Infinite? I answer, not by reason. It is the office of reason to distinguish and define. The Infinite, therefore, cannot be ranked among its objects. You can only apprehend the Infinite by a faculty superior to reason, by entering into a state in which you are your finite self no longer—in which the divine essence is communicated to you. This is ecstasy. It is the liberation of your mind from its finite consciousness. Like can only apprehend like; when you thus cease to be finite, you become one with the infinite. In the reduction of your soul to its simplest self, its divine essence, you realise this union, this identity. Plotinus: Letter to Flaccus CHAPTER 1 ANCIENT MYSTERIES Cosmic Consciousness The goal of all major esoteric traditions and of all world religions is entry into a higher kingdom of nature, into the realm of the gods. This kingdom is known as the Fifth Kingdom, and one’s awareness and experience of its world constitute what is referred to as the superconscious experience. It has been described by all those who have had this extraordinary glimpse of another world, in ecstatic terms, as a state of boundless being and bliss in which one’s individual consciousness merges with the universal consciousness, with the Godhead. It is a state of beingness and awareness that far surpasses one’s usual limited, narrow view of reality and transports one, for a brief moment, beyond the limits of time and space into another dimension. -

And the English Imperative: a Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi

“Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Prof. Laura Sterponi, Chair Prof. Claire Kramsch Prof. Robin Lakoff Fall 2013 “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi Copyright © 2013 By Usree Bhattacharya Abstract “Globalization” and the English Imperative: A Study of Language Ideologies and Literacy Practices at an Orphanage and Village School in Suburban New Delhi by Usree Bhattacharya Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura Sterponi, Chair This dissertation is a study of English language and literacy in the multilingual Indian context, unfolding along two analytic planes: the first examines institutional discourses about English learning across India and how they are motivated and informed by the dominant theme of “globalization,” and the second investigates how local language ideologies and literacy practices correspond to these discourses. An ethnographic case study, it spans across four years. The setting is a microcosm of India’s own complex multilingualism. The focal children speak Bengali or Bihari as a first language; Hindi as a second language; attend an English-medium village school; and participate daily in Sanskrit prayers. Within this context, I show how the institutional discursive framing of English as a prerequisite for socio- economic mobility, helps produce, reproduce, and exacerbate inequalities within the world’s second largest educational system. -

Exigency of Intellectuality and Pragmatic Reasoning Against Credulity

© 2019 JETIR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) EXIGENCY OF INTELLECTUALITY AND PRAGMATIC REASONING AGAINST CREDULITY. (COUNTERFEIT PROPHECY, SUPERSTITION, ASTROLOGY AND VIGILANT GLOBE) Bhaskar Bhuyan India, State- Assam, Dist- Lakhimpur, Pin-787023 ABSTRACT Along with advancement and technology, still some parts of the globe are greatly affected by fake beliefs. Future is unpredictable and black magic is superstition. Necessity lies in working for future rather than knowing it. Lack of intelligence is detrimental for a society. Astrology is not a science, Astronomy is science. Astrologers predict by the influence of planets and they create a psychological game. In other words they establish a perfect marketing and affect the life of an individual in every possible way. Superstition is still ruling and it is degrading the development. Key words: Superstition, Astrology and black magic. 1.0 INTRODUCTION: The globe is still not equally equipped with development, advancement and intellectuality. Some 5000 years ago, superstition started to merge out from the ancient Europe and got spread to entire Globe. Countries like China, Greece, India, United Kingdom, Japan, Thailand, Ireland, Italy, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal etc are influenced by black magic, superstition, astrology and fake Beliefs. Almost 98 countries out of 195 are affected by credulity. Orating the scenario of ancient time and comparing it with the present arena, it is still not degraded. The roots of this belief starts from the village and gets spread socially due to migration and social media across the entire district, state and country. 2.0 SUPERSITION IN VARIOUS COUNTRIES: 2.1 JAPAN: 1. -

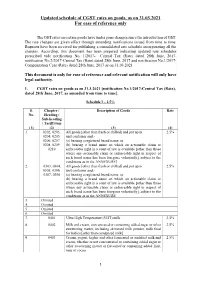

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M. -

5. the Other Side of Freedom of Religion in India

2015 (2) Elen. L R 5. THE OTHER SIDE OF FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN INDIA Vipin Das R V1 Introduction Freedom of religion is considered as the precious possession of every individual from the inception of mankind (Harold E., 2002).2 Every modern nation in the world, in their Constitutions, clearly establishes the right to freedom of religion, belief, faith, thought, and expression of all these freedoms to all its citizens. Many a time, these expressions and practices attributed to religions, faith and beliefs become blind. Citizens or the people following such blind belief and faith on religion and practising so-called religious activities infringes forcefully the human right of others to live with dignity and status. The recent news and reports from print and television media reveals the truth that exploitations in the name of black magic are on the rise in Kerala as well as in India.3 Superstition- General meaning. The term „Superstition‟ is a complex term having no clear definition. In practical sense superstition is an elastic term which could be at once narrowly defined to exclude individual practice and also can be stretched to include a wide spectrum of beliefs, rites, 1 Research Scholar, NUALS. Email: [email protected] 2 See generally Lurier, Harold E. (2002), A History of the Religions of the World, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation Publishers. 3 See for examples, The search list generated in NDTV website for the key word “Black Magic”, a minimum of 40 recent reports could be identified. URL: http://www.ndtv.com/topic/black-magic (Last -

Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: the Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues

American Journal of www.biomedgrid.com Biomedical Science & Research ISSN: 2642-1747 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mini Review Copyright@ Abdul Kader Mohiuddin Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: The Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues Abdul Kader Mohiuddin* Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Bangladesh To Cite This Article: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin. Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: The Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2019 - 4(5). AJBSR.MS.ID.000829. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000829 Received: August 13, 2019 | Published: August 20, 2019 Abstract Personal care products and facial cosmetics are commonly used by millions of consumers on a daily basis. Direct application of cosmetics on human skin makes it vulnerable to a wide variety of ingredients. Despite the protecting role of skin against exogenous contaminants, some of the ingredients in cosmetic products are able to penetrate the skin and to produce systemic exposure. Consumers’ knowledge of the potential risks of the frequent application of cosmetic products should be improved. While regulations exist in most of the high-income countries, in low income countries of heavy metals are strict. There is a need for enforcement of existing rules, and rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of these regulations. The occurrencethere -

Questions and Answers on DEATH

Questions and Answers on DEATH. What is Go-dan? Go-dan? Go means the cow and dan means gift. So Go-dan is the giving the gift of a cow to a Brahmin. This is an extremely important prayer that one performs in one's life. When should Go-Daan puja be performed? Many people are under the impression that this prayer is only performed when one is about to die. This is a great misunderstanding. This prayer should be done when one is fit and in a healthy mind. When one performs this prayer when one is fit and healthy then its efficacy is increased 1000 fold, if a sick man makes the gift its efficacy is only a 100 fold. If his son gifts something on behalf of the dead, the gift is indirect and its efficacy is rendered as normal. (Garuda Purana Preta Kand Chapter 47 verses 37-38) What should be given in the Go-Daan puja? Sesame seed, iron, gold, cotton, salt, seven types of grains, earth and a cow. The dying person should give these 8 precious gifts to a brahmana. The wise have prescribed the gift of salt to be given freely and it opens the doorway to the other world. (Garuda Purana Preta Khanda chapter 4 verses 7-8,14) Why do Hindus perform cremation? In Hinduism, cremation is prescribed by our shastras and it is preferred means of disposal of the corpse. The others being disposing the body via water or burial. The most important reason for a cremation is that with the destruction of the body, the soul of the deceased, existing as the vaayuja shareera is no longer drawn to, or able to identify with the body. -

Non-Wood Forest Products in Asiaasia

RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/281994/28 Non-Wood Forest Products in AsiaAsia REGIONAL OFFICE FORFOR ASIAASIA AND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA)(RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THE UNITED NATIONS BANGKOK 1994 RAPA PUBLICATION 1994/28 1994/28 Non-Wood ForestForest Products in AsiaAsia EDITORS Patrick B. Durst Ward UlrichUlrich M. KashioKashio REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIAASIA ANDAND THETHE PACIFICPACIFIC (RAPA) FOOD AND AGRICULTUREAGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OFOF THETHE UNITED NTIONSNTIONS BANGKOK 19941994 The designationsdesignations andand the presentationpresentation ofof material in thisthis publication dodo not implyimply thethe expressionexpression ofof anyany opinionopinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country,country, territory, citycity or areaarea oror ofof its its authorities,authorities, oror concerningconcerning thethe delimitation of its frontiersfrontiers oror boundaries.boundaries. The opinionsopinions expressed in this publicationpublication are those of thethe authors alone and do not implyimply any opinionopinion whatsoever on the part ofof FAO.FAO. COVER PHOTO CREDIT: Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph PHOTO CREDITS:CREDITS: Pages 8,8, 17,72,80:17, 72, 80: Mr.Mr. MohammadMohammad Iqbal SialSial Page 18: Mr. A.L. Rao Pages 54, 65, 116, 126: Mr.Mr. Urbito OndeoOncleo Pages 95, 148, 160: Mr.Mr. Michael Jensen Page 122: Mr.Mr. K. J. JosephJoseph EDITED BY:BY: Mr. Patrick B. Durst Mr. WardWard UlrichUlrich Mr. M. KashioKashio TYPE SETTINGSETTING AND LAYOUT OF PUBLICATION: Helene Praneet Guna-TilakaGuna-Tilaka FOR COPIESCOPIES WRITE TO:TO: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the PacificPacific 39 Phra AtitAtit RoadRoad Bangkok 1020010200 FOREWORD Non-wood forest productsproducts (NWFPs)(NWFPs) havehave beenbeen vitallyvitally importantimportant toto forest-dwellersforest-dwellers andand rural communitiescommunities forfor centuries.centuries. -

Step by Step Explanation of the Full Wedding Ceremony

Step by Step Explanation of the Full Wedding Ceremony The marriage is the biggest, most elaborate, magnificent, spectacular and impressive of all the life cycle rituals in a Hindu's life. Of course what's given below is just a simple format. Many areas of India perform the wedding with slight variations. I am enlightening you on the most important parts as explanation of each part of the wedding will make this article rather voluminous. This is part 2 of the marriage rites with part one dealing with the preliminaries of the wedding. The marriage ceremony may be divided into three parts. Summary: Part One Reception of the bridegroom and his parents by the bride's parents at the entrance gate of the hall. The reception of the bridegroom on the stage and giving of presents by bride's father. Bride's parents give their daughter away to the bridegroom. Part Two Marriage ceremony proper Sacred Fire Ceremony Solemn vows and joining hands Stone-stepping ceremony Fried-rice (popcorn) offered as oblations into the sacred Fire. Marriage nuptial knot Walking around the Sacred Fire taking holy vows. The ceremony of Seven steps Part Three Benediction (blessings) My humble advise if the wedding is taking place at 11h00 sharp (Do note - this is an example time) the bride and groom should be at the hall around an hour before the wedding proper starts... The Samdhimilan suggested time should be around 10h20. The Parchan Puja suggested time should be around 10h25. The Dwaar Puja suggested time should be around 10h40. The Groom who walks in with his entourage should walk in around 10h50. -

Volume 11 Number 4 October-December 2019

I Volume 11 Number 4 October-December 2019 International Journal of Nursing Education Editor-in-Chief Amarjeet Kaur Sandhu Principal & Professor, Ambika College of Nursing, Mohali, Punjab E-mail: [email protected] INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD NATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1. Dr. Arnel Banaga Salgado (Asst. Professor) 4. Fatima D’Silva (Principal) Psychology and Psychiatric Nursing, Center for Educational Nitte Usha Institute of nursing sciences, Karnataka Development and Research (CEDAR) member, Coordinator, 5. G.Malarvizhi Ravichandran RAKCON Student Affairs Committee,RAK Medical and PSG College of Nursing, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu Health Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates 6. S. Baby (Professor) (PSG College of Nursing, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, Ministry of Health, New Delhi 2. Elissa Ladd (Associate Professor) MGH Institute of Health Professions Boston, USA 7. Dr. Elsa Sanatombi Devi (Professor and Head) Meidcal Surgical Nursing, Manipal Collge of nursing, Manipal 3. Roymons H. Simamora (Vice Dean Academic) Jember University Nursing School, PSIK Universitas Jember, 8. Dr. Baljit Kaur (Prof. and Principal) Jalan Kalimantan No 37. Jember, Jawa Timur, Indonesia Kular College of Nursing, Ludhiana, Punjab 4. Saleema Allana (Assistant Professor) 9. Mrs. Josephine Jacquline Mary.N.I (Professor Cum AKUSONAM, The Aga Khan University, School of Nursing Principal) Si-Met College of Nursing, Udma, Kerala and Midwifery, Stadium Road, Karachi Pakistan 10. Dr. Sukhpal Kaur (Lecturer) National Institute of Nursing 5. Ms. Priyalatha (Senior lecturer) RAK Medical & Health Education, PGIMER, Chandigarh Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah,UAE 11. Dr. L. Eilean Victoria (Professor) Dept. of Medical Surgical 6. Mrs. Olonisakin Bolatito Toyin (Senior Nurse Tutor) Nursing at Sri Ramachandra College School of Nursing, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo of Nursing, Chennai, Tamil Nadu State, Nigeria 12. -

Cosmetics, Perfumery Compounds, Flavours &Amp

Cosmetics, Perfumery Compounds, Flavours & Essential Oils, Essential Perfume Oil, Cosmetics Fragrances, Perfumes & Fragrances, Aromatic Oils, Chemicals, Attar, Essences, Toiletries, Nail Polish, Hair Care, Personal Care, Skin Care, Makeup, Beauty Projects We can provide you detailed project reports on the following topics. Please select the projects of your interests. Each detailed project reports cover all the aspects of business, from analysing the market, confirming availability of various necessities such as plant & machinery, raw materials to forecasting the financial requirements. The scope of the report includes assessing market potential, negotiating with collaborators, investment decision making, corporate diversification planning etc. in a very planned manner by formulating detailed manufacturing techniques and forecasting financial aspects by estimating the cost of raw material, formulating the cash flow statement, projecting the balance sheet etc. We also offer self-contained Pre-Investment and Pre-Feasibility Studies, Market Surveys and Studies, Preparation of Techno-Economic Feasibility Reports, Identification and Selection of Plant and Machinery, Manufacturing Process and or Equipment required, General Guidance, Technical and Commercial Counseling for setting up new industrial projects on the following topics. Many of the engineers, project consultant & industrial consultancy firms in India and worldwide use our project reports as one of the input in doing their analysis. We can modify the project capacity and project