Working-Class and Memory Policy in Post-Industrial Cities: Łódź, Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAM Approach to Digital Game Preservation And

Drawing Things Together: Understanding the Challenges and Opportunities of a Cross- LAM Approach to Digital Game Preservation and © Centrum för kulturpolitisk forskning Exhibition Nordisk Kulturpolitisk Tidsskrift, ISSN Online: 2000-8325 vol. 22, Nr. 2-2019 s. 332–354 Patrick Prax Dr. Patrick Prax is assistant professor at the Department of Game Design at Uppsala DOI: https://doi.org/10.18261/ University. Patrick has a PhD in Media Studies from the Informatics and Media Department issn.2000-8325/-2019-02-08 at Uppsala University. Patrick´s work centers around digital games as participatory culture. He has written his dissertation about co-creative game design and has given a Uppsala RESEARCH PUBLICATION University TEDx talk about the topic. He has been working in a research project at the Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology and writes about participation in preservation and exhibition of games as cultural heritage. He is also serving as board member for the Cultural Heritage Incubator of the Swedish National Heritage Board. [email protected] Björn Sjöblom Björn Sjöblom, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Child and Youth Studies at Stockholm University. He works in a variety of areas related to discourse and interaction, both by and about children and youth. For the most part, his studies focus on interaction in various forms of digital media, especially in games. His research includes studies of teenagers in internet cafés, interaction in videomediated gaming,(such as on Youtube), and representations of children in digital games. Of special interest are also questions of digital media as cultural heritage, and of young people’s relationship to esport. -

Pyynikki Circuit

Pyynikki Circuit Pyynikki is a district and a nature reserve in Tampere, Finland. It is located in the Pyynikinharju ridge, between the city center and the western district of Pispala. Pyynikinharju is the highest esker in the world, rising 85 meters above the level of lake Pyhäjärvi.Tampere Circuit was a motorsport race track which ran on public streets of Pyynikki. Pyynikki is a district and a nature reserve in Tampere, Finland. It is located in the Pyynikinharju ridge, between the city center and the western district of Pispala. Tampere Circuit was a motorsport race track located in Tampere, Finland. The route was used for an annual motorcycle race called Pyynikinajo in 1932-1939 and 1946-1971. In 1962 and 1963, the circuit hosted the Finnish motorcycle Grand Prix, a round of the Grand Prix motorcycle racing world championship. The track ran on public streets of the Pyynikki district. The event was banned after 1971 due to general safety concerns. street circuit in Tampere, Finland. Pyynikki Circuit (Q2120091). From Wikidata. Jump to navigation Jump to search. street circuit in Tampere, Finland. Tampere Circuit. edit. Language. Pyynikki. New York has Central Park, but how many cities can boast about having a central forest? One of the Tampere city centre neighbourhoods, Pyynikki, is home to a gorgeous pine tree forest on top of a ridge. In the forest there is an illuminated jogging trail that becomes a skiing trail in the winter, and the view from the high cliffs will take your breath away. Het Pyynikki Circuit is een voormalig stratencircuit in de Finse stad Tampere. -

036-Bengtsson-Finlan

Unequal poverty and equal industrialization: Finnish wealth, 1750–1900 Erik Bengtsson., Anna Missiaia, Ilkka Nummela and Mats Olsson For presentation at the First WID.world Conference, Paris, 14-15 December 2017 Preliminary! All comments welcome 9 918 words, 10 tables, 3 figures Abstract This paper presents for the first time estimates of wealth and its distribution for Finland from 1750 to 1900. Finland is a highly interesting case for historical inequality studies, as a poor and backward European country which embarked on industrialization only in the late nineteenth century. This gives us the opportunity to re-consider common theories and arguments about the relationships between economic growth and inequality. Using wealth data from probate inventories, we show that Finland was very unequal between 1750 and 1850, with the top decile owning about 85 per cent of total wealth. This means that Finland was more unequal than much more advanced economies such as Britain, France and the US, which goes against the common assumption of poorer economies being more equal. It was also more unequal than its most immediate term of comparison, Sweden. Moreover, when industrialization took off in Finland and contra the commonplace assumption of industrialization increasing inequality (see the Kuznets Curve and its later developments), inequality started a downward trajectory where the share of the top decile decreased from 87 per cent in 1850 to 77 per cent in 1900, 71 per cent in 1910 and 64 per cent in 1920. We show that the high inequality from 1750 to 1850 is driven from the bottom, by a large share of the population owning nothing or close to nothing of value, while economic development after 1850 is pro-equality since the ownership of forests, since long in the hands of the peasantry, provided new export opportunities as pulp and paper became very valuable. -

Useful Info Explore the History Pop By

Naistenlahden voimalaitos 7 EXPLORE THE HISTORY Satamatoimisto 6 6 37 5 Visit the Finlayson and Tampella areas to witness the new life Myllysaari Kekkosenkatu 2 4 Rauhaniementie of the industrial heritage sites. Admire the national landscape, den Parantolankatu kanlah katu 11 Näsijärvi Sou2 15 historical red brick buildings and roaring rapids. Operational in- Pursikatu 19 Kekkosentie ARMONKALLIOHelenankatu dustrial areas and hydroelectric plants coexist in harmony with 95,2 5 19 esplanadi 5 13 Särkänniemi Tampellan 21 4 Soukkapuisto 11 restaurants, movie theatre, cafés, and stores that nowadays 2 16 2 9 7 1 Kaivokatu Tunturikatu 1 8 Helenankuja 5 inhabit some of the former industrial buildings. Walk down by 2 Tammelan puistokatu Tammelan 25 8 6 3 1 7 the rapids towards Kehräsaari where you fi nd the idyllic old 5 6 2 7 3 4 Pohjoinen 4 2 Siltakatu Naistenlahdenkatu Haarakatu 2 Kaarikatu 11 Pohjankulma 6 Moisionkatu factory milieu, which is worth visiting. It is a home to design Välimaankatu6 katu 5 Välimaanpolku Huvipuisto 8 8 2 5 2 5 13 5 3 tu and artisan boutiques, restaurants and an independent Yrjön äka 5 31 TOURIST MAP 8 6 7 25 Kauppi Pajasaari Törngrenin Ihanakatu13 15 17 Pohjolankatu movie theatre Niagara. An es- Sara Hildènin taidemuseo Lepp ratapihankatu 9-11 aukio Rohdin kuja 2-4 VISITTAMPERE.FI Näsinneula 32 30 33 sential part of the city’s history, Kaivokatu 22 10 15 7 Pohjolankatu 18-20 10 13 11 Verstaankatu 11 2 9 10 12 esplanadi 28 5 29 58 Kihlmaninraitti 9 3 and some of the architectural Tel: +358 3 5656 6800 28 Siltakatu 4 sandranenonen 17 6 Akvaario-Planetaario TAMPELLA 7 10 1 pearls of Tampere, are Finlayson Osmonkatu Osmonraitti 9 14 visittampere@visittampere.fi Keernakatu 7 2 2 3 24 Palace, Näsilinna and Tampere Osmonpuisto 17 Runoilijan Tampellan Pajakatu 9 1 Pellavan- 14 Annikinkatu Cathedral. -

Digra 2020 CONFERENCE

Plan to hold the DiGRA 2020 CONFERENCE 3-6 June 2020 in Tampere, Finland Plan to hold the DIGRA 2020 CONFERENCE 3-6 June 2020 in Tampere, Finland CONTENTS In Brief ......................................................................................................................................3 Venue........................................................................................................................................3 Conference .................................................................................................................................4 Travel and Accommodation ..............................................................................................................6 Organization ................................................................................................................................7 Publicity & Dissemination ................................................................................................................9 Other Considerations ......................................................................................................................9 2 IN BRIEF DiGRA 2020 will be organised in Tampere, Finland; the conference dates are 3-6 June 2020 (with a pre-conference day in 2nd June 2020). Co-hosted by the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult) and three universities, the theme of DiGRA 2020 is set as Play Everywhere. The booked venues are LINNA building of Tampere University, and Tampere Hall – the largest conference centre in the -

Mess in the City at the Moment, It's the New Tram Network Being Built

mess in the city at the moment, it’s the new tram network being built Moro! *) -something that we worked for years to achieve and are really proud of. Welcome to Tampere! So welcome again to our great lile city! We are prey sure that it’s the best Tampere is the third largest city and the second largest urban area in Finland, city in Finland, if not in the whole Europe -but we might be just a lile bit with a populaon of closer to half a million people in the area and just over biased about that… We hope you enjoy your stay! 235 000 in the city itself. The Tampere Greens Tampere was founded in 1779 around the rapids that run from lake Näsijärvi to lake Pyhäjärvi -these two lakes and the rapids very much defined Tampere and its growth for many years, and sll are a defining characterisc of the *) Hello in the local dialect city. Many facories were built next to the energy-providing Tammerkoski rapids, and the red-brick factories, many built for the texle industry, are iconic for the city that has oen been called the Manchester of Finland -or Manse, as the locals affeconately call their home town. Even today the SIGHTS industrial history of Tampere is very visible in the city centre in the form of 1. Keskustori, the central square i s an example of the early 1900s old chimneys, red-brick buildings and a certain no-nonsense but relaxed Jugend style, a northern version of Art Nouveau. Also the locaon of atude of the local people. -

RANTATIE 43, 33250 TAMPERE Visualisointikuvassa Taiteilijan Näkemys Erinan Julkisivusta JÄRVEN RAUHA KOTONA KAUPUN- GISSA

ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA RANTATIE 43, 33250 TAMPERE Visualisointikuvassa taiteilijan näkemys Erinan julkisivusta JÄRVEN RAUHA KOTONA KAUPUN- GISSA Vedellä on aina ollut erityislaatuinen merkitys suo- malaisille. Sen lisäksi että saamme nauttia maailman puhtaimmasta vedestä, se tarjoaa meille ympärivuo- tisen virkistäytymisen muun muassa uinnin, veneilyn 4 tai kalastamisen muodossa. Maisema on kuin postikortista. Järvimaisemaa par- vekkeeltaan ihastellessa saattaa jopa unohtaa, että asuu kaupungissa. Kaupunkiasuminen ei tarkoita, että omista ehdoistaan tulee luopua. Santalahti yhdistää unelman urbaanista asumisesta järvimaise- masta tinkimättä. Santalahdesta muodostui aikanaan keskeinen teol- lisuusalue sijaintinsa ansiosta Näsijärven rannalla, Tampereen keskustan kainalossa. Tulitikkujen, pa- perin ja pahvin valmistus kukoisti ja alueen yritykset olivat suuri paikallinen työllistäjä. Santalahden vanhat tukkilaiturit ovat sittemmin kadonneet ja teollisuus alueella lakannut. Tilalle on syntynyt hiekkaranta, venesatama ja suuri virkistäy- tymiselle pyhitetty puisto. Teollisuusalue muuttuu asteittain uudeksi ja monimuotoiseksi kaupungi- nosaksi upeilla järvinäkymillä ja virkistysmahdolli- suuksilla, aivan keskustan äärelle. Elämä on onnellisinta kauniin Näsijärven rannalla, kaupungin keskellä. Visualisointikuvassa taiteilijan näkemys asunnosta A13. ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA ASUNTO OY TAMPEREEN PISPARANNAN ERINA TAMPEREEN OMINTAKEISIN KAUPUNGIN- OSA Tampereen Santalahti herää uuteen elämään, kun vanha teollisuusalue -

Ment of Collections in Tampere Museums

NORDI S K M US EOLOGI 1998•2, S . 51-68 How TO MANAGE COLLECTIONS? - THE PROBLEM OF MANAGE MENT OF COLLECTIONS IN TAMPERE MUSEUMS Ritva Palo-oja & Leena Willberg What do you do, when collections include 200, 000 objects, and only halfof them are within the management system? What do you do with objects that have been damaged by fire or in transfers between collections? These questions prompted the collection management team of Tampere Museums to develop a value classification system in 1994. This system has been applied since, and has proved to be a practical tool for collection management. The system has already been refined through experience. We hope that this article will provoke discussion and motivate museums to develop common collection management methods. TAMPERE MUSEUMS further strengthened by the establishment of a railway network. The first railway con The collection policy of the Tampere nection was opened in 1876 between Museums is to accumulate the cultural Hameenlinna and Tampere. Industrialists heritage of the Tampere Region, maintain realised the power potential of the Tammer it and put it on display. koski Rapids, and one by one the textile The city of Tampere was founded in industry, the engineering industry and the 1779, and is the largest inland city in paper and shoe industries started to develop Scandinavia. It is located on the historical and became important branches of Finnish junction of centuries old waterways and industry as a whole. After decades of struc roads on the isthmus of lakes Nasijarvi and tural change, Tampere has become an Pyhajarvi, on both sides of the Tammer important centre in the IT industry and a koski Rapids. -

Pispala Visio © 2008 Rakennusoikeus -Ryhmä

”Tasavertaisuus, Oikeudenmukaisuus, Laillisuus” Pispala Visio © 2008 Rakennusoikeus -ryhmä Pispalan asemakaavan muutosta pohjustavan Rakennusoikeus- työryhmän julkaisu 2008: PISPALA VISIO Näsijärveltä Ilmasta Pyhäjärveltä Julkaisun kokoajat: Antti Ivanoff, Aarne Raevaara, Mårten Sjöblom, Juho Kuusinen Valokuvat: Antti Ivanoff, Juho Kuusinen, Aarne Raevaara Ilmakuvat: Lentokuva Vallas 2008, http://suomi.ilmasta.fi Kustantaja: Tampere Pispala - Rakennusoikeus –ryhmä ISBN 978-952-67061-1-5 Versio 1.0 1 Pispala Visio © 2008 Rakennusoikeus -ryhmä SISÄLLYS 1 PISPALA VISIO ........................................................................................................................4 2 PISPALALAINEN RAKENTAMISKULTTUURI ................................................................5 2.1 PISPALAA RAKENNETAAN VIELÄ ...........................................................................................5 2.2 KEINOJA RAKENNETUN KULTTUURIYMPÄRISTÖN SÄILYTTÄMISEEN ......................................6 2.3 JULKISIVUMUUTOKSILLA ON MAHDOLLISUUS KEHITTÄÄ SEKÄ ASUMISMUKAVUUTTA ETTÄ PISPALAN ILMETTÄ ...........................................................................................................................8 2.4 RAKENNUSTEN LAAJENTAMINEN ON OSA PISPALAN KULTTUURIHISTORIALLISTA ERITYISPIIRRETTÄ ...........................................................................................................................11 2.5 UUDISRAKENTAMINEN SOPII PISPALAAN , MYÖS VANHAT RAKENNUKSET OVAT AIKANAAN OLLEET UUSIA .................................................................................................................................13 -

Finnish Nationalism

State and Revolution in Finland Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Sébastien Budgen (Paris) David Broder (Rome) Steve Edwards (London) Juan Grigera (London) Marcel van der Linden (Amsterdam) Peter Thomas (London) volume 174 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hm State and Revolution in Finland By Risto Alapuro LEIDEN | BOSTON This title is published in Open Access with the support of the University of Helsinki Library. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. First edition of State and Revolution in Finland was published in 1988 by University of California Press. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2018043939 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1570-1522 ISBN 978-90-04-32336-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-38617-4 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by the Authors. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

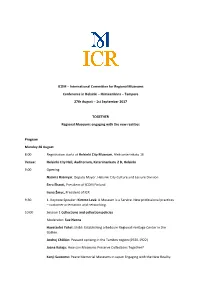

Program ICR Conference 2017

ICOM – International Committee for Regional Museums Conference in Helsinki – Hämeenlinna – Tampere 27th August – 1st September 2017 TOGETHER Regional Museums engaging with the new realities Program Monday 28 August 8:00 Registration starts at Helsinki City Museum, Aleksanterinkatu 16 Venue: Helsinki City Hall, Auditorium, Katariinankatu 2 B, Helsinki 9:00 Opening Nasima Rasmyar, Deputy Mayor, Helsinki City Culture and Leisure Division Eero Ehanti, President of ICOM Finland Irena Žmuc, President of ICR 9:30 1. Keynote Speaker: Kimmo Levä: A Museum is a Service. New professional practices – customer orientation and networking. 10:00 Session 1 Collections and collection policies Moderator: Sue Hanna Havatzelet Yahel: Shibli: Establishing a Bedouin Regional Heritage Center in the Galilee. Andrej Chilikin: Peasant uprising in the Tambov region (1920-1922). Jaana Kataja: How can Museums Preserve Collections Together? Kenji Saotome: Peace Memorial Museums in Japan Engaging with the New Reality. 11:00 Coffee 11:15 Session 2 Collections and collection policies Moderator: Tuulia Tuomi Irena Žmuc and Barbara Savenc: New Reality – New Collection? Blanca Gonzalez: From one century to another. Four museums in Merida. 11:45 Kenji Saotome: Presentation of ICOM General in Kyoto 2019 12:15 Discussion 12:30 Tiina Merisalo: The New Helsinki City Museum – The Museum of the Year in Finland 2017 12:45 Lunch 13:45 Helsinki City Museum guided tour 15:00 Session 3 Topographies of Fear, Hope and Anger Moderator: Jane Legget 15:00 2. Keynote Speaker: Jette Sandahl: Topographies of Fear, Hope and Anger 15:45 Round Table Workshop The ICOM Committee of Museum Definition, Prospects and Potentials is running a series of round-tables across the world to explore the future of museums and the shared, but also the profoundly dissimilar conditions, values and practices of museums in diverse and rapidly changing societies. -

ASEMAKAAVAMUUTOS SELOSTUS Ehdotusvaihe 7.1.2019 2

PISPALAN ASEMAKAAVAN UUDISTAMISEN II-VAIHE Asemakaavat nro 8309 ja 8310 ASEMAKAAVAMUUTOS SELOSTUS Ehdotusvaihe 7.1.2019 2 TIIVISTELMÄ Kaava-alueen sijainti ja luonne Pispala sijaitsee noin kolmen kilometrin päässä Tampereen keskustasta länteen Näsi- ja Pyhäjärven välisellä harjulla. Pispalan asemakaava uudistetaan kolmessa eri vaiheessa. I-vaiheen kaavat 8256 ja 8257 ovat tulleet voimaan 13.3.2017. Nyt laadittavan II-vaiheen kaava-alueet 8309 ja 8310 sijaitsevat Ylä- ja Ala-Pispalan sekä Santalahden kaupunginosien alueella Pispalan valtatien molemmin puolin, kaava-alueeseen kuuluu myös vähäisiä alueita Hyhkyn ja Särkänniemen kaupunginosista. Kaavamuutosalue on itä-länsisuunnassa noin 1,8 km pitkä ulottuen Ratakadulta Pohjanmaantiehen. Pohjoisessa alue rajautuu Porin rataan ja etelässä Uittotunnelinkatuun, Tahmelan viertotiehen ja Uittoyhtiönkatuun. Valmisteluvaiheessa päädyttiin rajaamaan Ratakadun asuinkiinteistöt kaava-alueen 8309 ulkopuolelle, koska niiden kaupunkikuvallista ja toiminnallista tilannetta kahden melua tuottavan liikenneväylän välissä on tarkoituksenmukaista tarkastellavasta Santalahden rakentumisen edettyä. Kaava-alueen 8310 rajausta tarkistettiin liittämällä siihen Punaisen tukkitien uoman eteläosa, koska se on osa kulttuurihistoriallisesti arvokasta tukkitien kokonaisuutta. Kaavaan liitetty alue käsittää korttelin 1088 sekä puisto- ja katualuetta Tahmelan viertotien, Pulkkasaarenkadun, Saunasaarenkadun ja Pyhäjärven rannan välisellä alueella. Pispala tunnetaan työväestön ilman valvontaa rakentamana puutaloalueena. Rakennuskanta