Does Hugging Provide Stress-Buffering Social Support?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Global Measure of Perceived Stress Author(S): Sheldon Cohen, Tom Kamarck and Robin Mermelstein Reviewed Work(S): Source: Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol

A Global Measure of Perceived Stress Author(s): Sheldon Cohen, Tom Kamarck and Robin Mermelstein Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Dec., 1983), pp. 385-396 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2136404 . Accessed: 24/10/2012 13:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Health and Social Behavior. http://www.jstor.org A GLOBAL MEASURE OF PERCEIVED STRESS 385 Richardson,Jean, and JulieSolis Wiggins,Jerry S. 1982 "Place ofdeath of Hispanic cancer patients 1973 Personalityand Prediction:Principles of in Los Angeles County." Unpublished PersonalityAssessment. Reading, MA: manuscript. Addison-WesleyPublishing Co. Stoddard,Sandol WilderFoundation 1978 The HospiceMovement. Briarcliff Manor, 1981 Carefor the Dying: A Studyof the Need for New York: Steinand Publishers. Hospice in RamseyCounty, Minnesota. A Valle, R., and L. Mendoza reportto the NorthwestArea Foundation 1978 The Elder Latino. San Diego, CA: Cam- fromthe AmherstH. WilderFoundation, panilePress. 355 WashingtonSt., St. Paul, MN. A GlobalMeasure of PerceivedStress SHELDON COHEN Carnegie-Mellon University TOM KAMARCK Universityof Oregon ROBIN MERMELSTEIN Universityof Oregon Journalof Healthand Social Behavior1983, Vol. -

Emotional Style and Susceptibility to the Common Cold

Emotional Style and Susceptibility to the Common Cold SHELDON COHEN,PHD, WILLIAM J. DOYLE,PHD, RONALD B. TURNER, MD, CUNEYT M. ALPER,MD,AND DAVID P. SKONER,MD Objective: It has been hypothesized that people who typically report experiencing negative emotions are at greater risk for disease and those who typically report positive emotions are at less risk. We tested these hypotheses for host resistance to the common cold. Methods: Three hundred thirty-four healthy volunteers aged 18 to 54 years were assessed for their tendency to experience positive emotions such as happy, pleased, and relaxed; and for negative emotions such as anxious, hostile, and depressed. Subsequently, they were given nasal drops containing one of two rhinoviruses and monitored in quarantine for the development of a common cold (illness in the presence of verified infection). Results: For both viruses, increased positive emotional style (PES) was associated (in a dose-response manner) with lower risk of developing a cold. This relationship was maintained after controlling for prechallenge virus-specific antibody, virus-type, age, sex, education, race, body mass, and season (adjusted relative risk comparing lowest-to-highest tertile ϭ 2.9). Negative emotional style (NES) was not associated with colds and the association of positive style and colds was independent of negative style. Although PES was associated with lower levels of endocrine hormones and better health practices, these differences could not account for different risks for illness. In separate analyses, NES was associated with reporting more unfounded (independent of objective markers of disease) symptoms, and PES with reporting fewer. Conclusions: The tendency to experience positive emotions was associated with greater resistance to objectively verifiable colds. -

PERCEIVED STRESS SCALE by Sheldon Cohen

PERCEIVED STRESS SCALE by Sheldon Cohen hosted by Copyright © 1994. By Sheldon Cohen. All rights reserved. Mind Garden, Inc. is a leading international publisher of psychological assessments, focusing on providing ease, access, speed, and flexibility. We are in the business of enabling access to validated psychological assessments and instruments. We serve the international, corporate, academic, and research communities by offering high-quality, proven instruments from prominent psychologists. www.mindgarden.com [email protected] (650) 322-6300 Save time and effort by administering this instrument with TransformTM! Let Mind Garden handle survey creation, data collection and scoring for you. Our TransformTM system allows you to easily manage participants with a variety of campaign options. TransformTM will administer the instrument and provide you with a .csv data file of the raw score, by scale. For most instruments you can also provide individual reports to participants or generate group reports. We can add demographics and other instruments, including non-Mind Garden instruments, to the survey with our Customization Services. If you find the Perceived Stress Scale useful, you might be interested in these other great Mind Garden instruments. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Understanding and Other instruments related to Adult (STAI-AD) Managing Stress Anxiety and Stress by Charles D. Spielberger by Robert Most and Theresa Muñoz The definitive instrument for This forty-page workbook These instruments measure measuring anxiety in adults. It offers individuals a anxiety or stress in a variety of clearly differentiates between the comprehensive approach to situations including test temporary condition of “state managing stress. The anxiety, school-related stress, anxiety” and the more general workbook includes basic and anxiety as a state-like and and long-standing quality of “trait strategies for: managing daily trait-like construct. -

Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis

Psychologkal Bulletin Copyright 1985 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1985, Vol. 98. No. 2, 31 0033-2909/85/$00.75 Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis Sheldon Cohen Thomas Ashby Wills Carnegie-Mellon University Cornell University Medical College The purpose of this article is to determine whether the positive association between social support and well-being is attributable more to an overall beneficial effect of support (main- or direct-effect model) or to a process of support protecting persons from potentially adverse effects of stressful events (buffering model). The review of studies is organized according to (a) whether a measure assesses support structure or function, and (b) the degree of specificity (vs. globality) of the scale. By structure we mean simply the existence of relationships, and by function we mean the extent to which one's interpersonal relationships provide particular resources. Special at- tention is paid to methodological characteristics that are requisite for a fair com- parison of the models. The review concludes that there is evidence consistent with both models. Evidence for a buffering model is found when the social support measure assesses the perceived availability of interpersonal resources that are re- sponsive to the needs elicited by stressful events. Evidence for a main effect model is found when the support measure assesses a person's degree of integration in a large social network. Both conceptualizations of social support are correct in some respects, but each represents a different process through which social support may affect well-being. Implications of these conclusions for theories of social support processes and for the design of preventive interventions are discussed. -

Cohen,1 William J

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article SOCIABILITY AND SUSCEPTIBILITY TO THE COMMON COLD Sheldon Cohen,1 William J. Doyle,2 Ronald Turner,3 Cuneyt M. Alper,2 and David P. Skoner2 1Carnegie Mellon University, 2University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and 3University of Virginia Health Sciences Center Abstract—There is considerable evidence that social relationships company are somehow protected from illness. Two factors of the Big can influence health, but only limited evidence on the health effects of Five personality factors can be viewed as combining to represent the the personality characteristics that are thought to mold people’s so- central components of sociability: extraversion, the personality dimen- cial lives. We asked whether sociability predicts resistance to infec- sion that reflects an individual’s preferences for social settings, and tious disease and whether this relationship is attributable to the agreeableness, the dimension of personality that underlies geniality quality and quantity of social interactions and relationships. Three (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Of these, only extraversion has been seri- hundred thirty-four volunteers completed questionnaires assessing ously considered in terms of its implications for health. Eysenck their sociability, social networks, and social supports, and six evening (1967) proposed that extraversion is characterized by low resting lev- interviews assessing daily interactions. They were subsequently ex- els of electrocortical and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity posed to a virus that causes a common cold and monitored to see who (Geen, 1997). Because activation of these systems is related to sup- developed verifiable illness. Increased sociability was associated in a pression of immune function, low activation would be expected to re- linear fashion with a decreased probability of developing a cold. -

Identifying Stress Variables Linking Socioeconomic Status and Smoking

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 3-28-2018 Identifying Stress Variables Linking Socioeconomic Status and Smoking Aaron French Waters Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Waters, Aaron French, "Identifying Stress Variables Linking Socioeconomic Status and Smoking" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4651. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTIFYING STRESS VARIABLES LINKING SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SMOKING A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Psychology by Aaron French Waters B.S., California Lutheran University (Thousand Oaks, CA), 2014 May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 Overview -

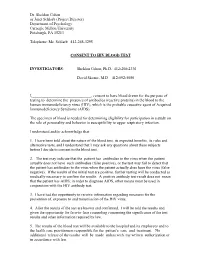

HIV Screening Consent Form

Dr. Sheldon Cohen or Janet Schlarb (Project Director) Department of Psychology Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Telephone: Ms. Schlarb 412-268-3295 CONSENT TO HIV BLOOD TEST INVESTIGATORS: Sheldon Cohen, Ph.D. 412-268-2336 David Skoner, M.D. 412-692-5080 I,______________________________, consent to have blood drawn for the purpose of testing to determine the presence of antibodies (reactive proteins) in the blood to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which is the probable causative agent of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). The specimen of blood is needed for determining eligibility for participation in a study on the role of personality and behavior in susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. I understand and/or acknowledge that: 1. I have been told about the nature of the blood test, its expected benefits, its risks and alternative tests, and I understand that I may ask any questions about these subjects before I decide to consent to the blood test. 2. The test may indicate that the patient has antibodies to the virus when the patient actually does not have such antibodies (false positive), or the test may fail to detect that the patient has antibodies to the virus when the patient actually does have the virus (false negative). If the results of the initial test are positive, further testing will be conducted as medically necessary to confirm the results. A positive antibody test result does not mean that the patient has AIDS; in order to diagnose AIDS, other means must be used in conjunction with the HIV antibody test. 3. I have had the opportunity to receive information regarding measures for the prevention of, exposure to and transmission of the HIV virus. -

Occasional Reviews Review of Psychosocial Stress and Asthma

1066 Thorax 1998;53:1066–1074 Occasional reviews Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.53.12.1066 on 1 December 1998. Downloaded from Review of psychosocial stress and asthma: an integrated biopsychosocial approach Rosalind J Wright, Mario Rodriguez, Sheldon Cohen Although consensus has emerged from the albeit equally important, determinants of clinical, social science, psychological, and asthma morbidity—for example, by influencing biological literature that psychosocial factors how children and their families perceive and aVect asthma morbidity in children, their role manage their asthma. Although no clear causal in the genesis, incidence, and symptomatology link between psychosocial stress and asthma has of asthma remains controversial since mecha- been established, this review provides a multi- nisms are not well understood. Three recent disciplinary transactional infrastructure that trends in medical research have led both clini- may guide future research priorities. cians and investigators to reconsider the role of psychosocial stress in asthma. Firstly, eVorts to Historical perspective define the aetiological risk factors for the The hypothesis of an association between stress development and expression of disease have and asthma emerges from a wide range of intensified in the face of rising trends in the clinical observation and evolving research. The prevalence and severity of asthma observed 1 general concept of the role of emotion and the worldwide. Thus far, focus on traditional social environment in disease is as old as medi- -

Facial Expressions of Emotion Reveal Neuroendocrine and Cardiovascular Stress Responses Jennifer S

Facial Expressions of Emotion Reveal Neuroendocrine and Cardiovascular Stress Responses Jennifer S. Lerner, Ronald E. Dahl, Ahmad R. Hariri, and Shelley E. Taylor Background: The classic conception of stress involves undifferentiated negative affect and corresponding biological reactivity. The present study hypothesized a new conception, disaggregating stress into emotion-specific, contrasting patterns of biological response. Specifically, it hypothesized contrasting patterns for indignation (comprised of anger and disgust) versus fear. Moreover, it hypothesized that facial expressions of these emotions would signal corresponding biological stress responses. Methods: Ninety-two adults engaged in annoyingly difficult stress-challenge tasks, during which cardiovascular responses, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis responses (i.e., cortisol), emotional expressions (i.e., facial muscle movements), and subjective emotional experience were assessed. Results: Pronounced individual differences emerged in specific emotional responses to the stressors. Analyses of facial expressions revealed that the more fear individuals displayed in response to the stressors, the higher their cardiovascular and cortisol responses to stress. By contrast, the more indignation individuals displayed in response to the same stressors the lower their cortisol levels and cardiovascular responses. Conclusions: Facial expressions of emotion signal biological responses to stress. Fear expressions signal elevated cortisol and cardiovascular reactivity; indignation signals attenuated cortisol and cardiovascular reactivity, patterns that implicate individual differences in stress appraisals. Rather than conceptualizing stress as generalized negative affect, studies can be informed by this emotion-specific approach to stress responses. Key Words: Cardiovascular, cortisol, emotion, facial expression, fear differs from anger and disgust in ways that imply the individual differences, stress possibility of diverging physiological and neuroendocrine stress responses. -

Sarah D. Pressman

SARAH D. PRESSMAN PERSONAL INFORMATION Assistant Professor of Psychology University of California, Irvine Psychology and Social Behavior, School of Social Ecology e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION & EMPLOYMENT 1996-2000 Mount Allison University Sackville, NB Canada n B.Sc., Biopsychology with Honors (Cum Laude) 2000-2003 Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA USA n M.S., Psychology Advisor: Sheldon Cohen (Social, Personality and Health Psychology) 2003-2006 Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA USA § Ph.D., Psychology Advisor: Sheldon Cohen (Social, Personality and Health Psychology) 2006-2008 University of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, PA USA § Post Doctoral Fellow in Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine 2008-2012 University of Kansas Lawrence, KS USA § Beatrice Wright Assistant Professor of Psychology 2013-current University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA USA § Assistant Professor of Psychology PUBLICATIONS & PRESENTATIONS PUBLICATIONS (in chronological order; *indicates a graduate student, ** indicates an undergraduate student) PUBLICATIONS, BOOKS, & Gallagher, M., Lopez, S., & Pressman, S.D. (in press). Optimism is Universal: Exploring the BOOK presence and benefits of optimism in a representative sample of the world. Journal of Personality. CHAPTERS Pressman, S.D., Gallagher, M. & Lopez, S. (in press). Is the Emotion-Health Connection a “First World Problem? Psychological Science. Lopez, S. & Pressman, S.D. (2012). Americans Use Their Strengths Least on Sundays: People Do More of What They Do Best on Positive Days. Gallup Journal Online. Pressman, S.D. & *Kraft, T.L. (in press; published on line October 2012). Grin and bear it: The influence of manipulated positive facial expression on the stress response. Psychological Science. (Note: Both authors contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors; publication will list authors alphabetically) Pressman, S.D. -

Can We Improve Our Physical Health by Altering Our Social Networks? Sheldon Cohen and Denise Janicki-Deverts

PERSPECTIVES ON PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Can We Improve Our Physical Health by Altering Our Social Networks? Sheldon Cohen and Denise Janicki-Deverts Carnegie Mellon University ABSTRACT—Persons with more types of social relationships It is not only studies of community samples that suggest that live longer and have less cognitive decline with aging, social integration has health benefits. More diverse networks are greater resistance to infectious disease, and better prog- also associated with better prognoses among those facing noses when facing chronic life-threatening illnesses. We chronic life threatening illnesses. For example, in longitudinal- have known about the importance of social integration prospective studies, more socially integrated individuals at high (engaging in diverse types of relationships) for health and risk for or suffering from cardiovascular disease develop less longevity for 30 years. Yet, we still do not know why having arterial calcification (Kop et al., 2005), have a lower incidence of a more diverse social network would have a positive in- stroke (Rutledge et al., 2008), and live longer (Rutledge et al., fluence on our health, and we have yet to design effective 2004) than do their less integrated counterparts. Greater social interventions that influence key components of the network network diversity is also associated with a decreased risk for the and in turn physical health. Better understanding of the recurrence of cancer (reviewed by Helgeson, Cohen, & Fritz, role of social integration in health will require research on 1998). how integrated social networks influence health relevant A graded relation between integration and better health was behaviors, regulate emotions and biological responses, found in many of these studies (e.g., Berkman & Syme, 1979; and contribute to our expectations and worldviews. -

Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091

bs_bs_banner Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091 Sheldon Cohen2 and Denise Janicki-Deverts Carnegie Mellon University Psychological stress was assessed in 3 national surveys administered in 1983, 2006, and 2009. In all 3 surveys, stress was higher among women than men; and increased with decreasing age, education, and income. Unemployed persons reported high levels of stress, while the retired reported low levels. All associations were indepen- dent of one another and of race/ethnicity. Although minorities generally reported more stress than Whites, these differences lost significance when adjusted for the other demographics. Stress increased little in response to the 2008–2009 economic downturn, except among middle-aged, college-educated White men with full-time employment. These data suggest greater stress-related health risks among women, younger adults, those of lower socioeconomic status, and men potentially subject to substantial losses of income and wealth.jasp_900 1320..1334 Potentially stressful life events are thought to increase risk for disease when one perceives that the demands these events impose tax or exceed a person’s adaptive capacity (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In turn, the percep- tion of stress may influence the pathogenesis of physical disease by causing negative affective states (e.g., feelings of anxiety and depression), which then exert direct effects on physiological processes or behavioral patterns that influence disease risk (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). Psychological stress is thought to influence a wide range of physiological processes and 1The eNation surveys and the preparation of this paper were supported by Johnson and Johnson (J & J) Consumer & Personal Products Worldwide, A Division of Johnson & Johnson Consumer Companies, Inc.