Measuring and Modeling the Trajectory of Visual Spatial Attention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Functions of the Brain: Perception, Attention and Memory

IFM LAB TUTORIAL SERIES # 6, COPYRIGHT c IFM LAB Cognitive Functions of the Brain: Perception, Attention and Memory Jiawei Zhang [email protected] Founder and Director Information Fusion and Mining Laboratory (First Version: May 2019; Revision: May 2019.) Abstract This is a follow-up tutorial article of [17] and [16], in this paper, we will introduce several important cognitive functions of the brain. Brain cognitive functions are the mental processes that allow us to receive, select, store, transform, develop, and recover information that we've received from external stimuli. This process allows us to understand and to relate to the world more effectively. Cognitive functions are brain-based skills we need to carry out any task from the simplest to the most complex. They are related with the mechanisms of how we learn, remember, problem-solve, and pay attention, etc. To be more specific, in this paper, we will talk about the perception, attention and memory functions of the human brain. Several other brain cognitive functions, e.g., arousal, decision making, natural language, motor coordination, planning, problem solving and thinking, will be added to this paper in the later versions, respectively. Many of the materials used in this paper are from wikipedia and several other neuroscience introductory articles, which will be properly cited in this paper. This is the last of the three tutorial articles about the brain. The readers are suggested to read this paper after the previous two tutorial articles on brain structure and functions [17] as well as the brain basic neural units [16]. Keywords: The Brain; Cognitive Function; Consciousness; Attention; Learning; Memory Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Perception 3 2.1 Detailed Process of Perception . -

Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding Protein (CPEB): a Prion-Like Protein As a Regulator of Local Protein Synthesis and Synaptic Plasticity

Luana Fioriti Research Associate Scholar The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University Weekly Seminar of the Fellows Program April 11th, 2007 Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB): a prion-like protein as a regulator of local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity 1.INTRODUCTION With this paper I would like to describe you what is my research project here at Columbia and how I am trying to address the many questions underlying my project by working everyday in the lab. But before doing this I feel somehow obliged to give you an introduction on the basic concepts of neurobiology. Therefore we will start with a brief definition and description of what is a neuron, how neurons interact to form synapse and neural circuits, how synapse activity can be modified and finally how these changes in synaptic activity underlie high cognitive processes such as learning and memory. After providing you this, I hope not too boring introduction, I will go deeper into the molecular aspects of these phenomenon and I will illustrate you the main goal of my research, which is to characterize the role of a particular protein called Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding protein with respect to the morphological and physiological changes that occur at the synapse after neuronal stimulation. Memory In psychology, memory is an organism's ability to store, retain, and subsequently recall information. Although traditional studies of memory began in the realms of philosophy, the late nineteenth and early twentieth century put memory within the paradigms of cognitive psychology. In recent decades, it has become one of the principal pillars of a new branch of science called cognitive neuroscience, a marriage between cognitive psychology and neuroscience. -

Verbal Learning Burbank Seminar Rooms Session 2B -Mathematical

Mathematical Psychology Meetings Stern Sail - Stanford Wednesday, August 23; 10-12 aojis, - BfoHadsy Lounges Session la - .'Neural nets Burbank Seminar Room:: Session lb - Verbal learning 1-3 pt-m. - Holiaday Lounge: Session 2s - Measurement and Sealing X Burbank Seminar Rooms Session 2b Mathematical Analysis of - Learning Data 3530-5 P«m. gfolladay Lounges Session 3: Symposium on Geometric Representation - of Psychological Data p«*nu - Reception at the Stanford Faculty Club Sburaday., August 29s 10-12 a^nu - felladay Lounge; Session 4a - Paychophyiiiesi Burbaok Seminar Ro®,n Sesuion Ub Concept learning and Social - Psychology Burbank Seminar Room Kb* 2'. Session Ue "" Choice Behavior 1-3 P»m*» - $3urbank Seminar Rooms Session _?a - Measurement and Scaling XI 1-5 P-n« - Holiaday Lounges Session Sb - Symposium on Models of Memory > Mathematical Psychology Meetings Stanford University August 23 and 29, 1968 PROGRAM Wednesday, August 28 10-12 a.m. Session la : Neural Nets Earl Hunt, University of Washington, A performance model for memory tasks based on a physiological model of retrieval. Robert J. Baron, Clarkson College of Technology, An associative memory system. Floyd Ratliff, Bruce Knight, and Norma Graham, The Rockefeller University, On tuning and amplification by lateral inhibition in a neural network. Naomi Weisstein, Loyola University, A Rashevsky-Landahl neural net for simulation of metacontrast. George Sperling, Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc., Energy models of binocular vision. 10-12 a.m. Session lb : Verbal Learning John Brelsford, Yale University, A finite Integer analysis of recall and recognition performance. William H. Batchelder, University of Illinois, A mathematical framework for item interrelationships during learning. -

VITA GEORGE SPERLING, UCI Distinguished Professor

VITA GEORGE SPERLING, UCI Distinguished Professor, Department of Cognitive Sciences, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, and Institute For Mathematical Behavioral Sciences, University of Cali- fornia, Irvine Business address: Dept. of Cognitive Sciences, SSPA3, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-5100 Tel: 949-824-6879 Fax: -2517 http://aris.ss.uci.edu/HIPLab Email: [email protected] Education: University of Michigan, B.S. Mathematics, 1955. Joint major in mathematics and biophysics. (Fulfilled requirements for summa cum laude.) Award: Gomberg Chemistry Prize and Scholarship, 1953-54. Memberships in collegiate honor societies: Phi Beta Kappa, Phi Eta Sigma, Phi Kappa Phi, Sigma Xi. Columbia University, M.A. Psychology, 1956. Harvard University, Ph.D. Psychology, 1959. Professional Employment: Research Assistant in Biophysics, Brookhaven National Laboratories, Upton, New York, summer, 1955. Research Assistant in Psychology, Harvard University, 1957-59. Member Technical Research Staff, Acoustical and Behavioral Research Center, AT&T Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, New Jersey: 1958 (summer); full-time, 1959-70; part-time, 1970-86. Instructor in Psychology (part-time), Department of Psychology, Washington Square College, New York University, 1962-63. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, Duke University, Spring, 1964. Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, Columbia University, 1964-65. Acting Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, 1967-68. Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 1969-70. Aw ard for a theoretical study of perception and short-term memory. Honorary Research Associate, Department of Psychology, University College, University of London, 1969-70. Professor of Psychology and Neural Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Science, New York University, 1970-1992. -

17. MEMORY in Psychology, Memory Is an Organism's Ability to Store, Retain, and Recall Information. Traditional Studies of Memor

17. MEMORY In psychology, memory is an organism's ability to store, retain, and recall information. Traditional studies of memory began in the fields of philosophy, including techniques of artificially enhancing the memory. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century put memory within the paradigms of cognitive psychology. In recent decades, it has become one of the principal pillars of a branch of science called cognitive neuroscience, an interdisciplinary link between cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Sensory memory Sensory memory corresponds approximately to the initial 200 - 500 milliseconds after an item is perceived. The ability to look at an item, and remember what it looked like with just a second of observation, or memorization, is an example of sensory memory. With very short presentations, participants often report that they seem to "see" more than they can actually report. The first experiments exploring this form of sensory memory were conducted by George Sperling (1960) using the "partial report paradigm." Subjects were presented with a grid of 12 letters, arranged into three rows of 4. After a brief presentation, subjects were then played either a high, medium or low tone, cuing them which of the rows to report. Based on these partial report experiments, Sperling was able to show that the capacity of sensory memory was approximately 12 items, but that it degraded very quickly (within a few hundred milliseconds). Because this form of memory degrades so quickly, participants would see the display, but be unable to report all of the items (12 in the "whole report" procedure) before they decayed. This type of memory cannot be prolonged via rehearsal. -

Memory Structures and Processes 107

Chapter 5 distribute Memory Structuresor and Processes post, Questions to Consider •• Is memory a process, a structure, or a system? •• How many types of memoriescopy, are there? •• Are there differences in the ways we store and retrieve memories based on how old the memories are?not •• What kind of memory helps us focus on a task? •• How Dodoes our memory influence us unintentionally? •• What are the limits of our memory? 105 Copyright ©2019 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 106 Cognitive Psychology Introduction: The Pervasiveness of Memory Memory is pervasive. It is important for so many things we do in our everyday lives that it is difficult to think of something humans do that doesn’t involve memory. To better understand its importance, imagine trying to do your everyday tasks without memory. When you first wake up in the morning you know whether you need to jump out of bed and hurry to get ready to leave or whether you can lounge in bed for a while because you remember what you have to do that day and what time your first task of the day begins. Without memory, you would not know what you needed to do that day. In fact, you would not know who you are, where you are, or what you are supposed to be doing at any given moment. It would be like waking up disoriented every minute. There are, in fact, individuals who must live their lives without the aid of these kinds of memories. -

Lifetime of Human Visual Sensory Memory: Properties and Neural Substrate

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons IRCS Technical Reports Series Institute for Research in Cognitive Science January 1999 Lifetime of Human Visual Sensory Memory: Properties and Neural Substrate Wei Yang University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports Yang, Wei, "Lifetime of Human Visual Sensory Memory: Properties and Neural Substrate" (1999). IRCS Technical Reports Series. 42. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/42 University of Pennsylvania Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Technical Report No. IRCS-99-03. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/42 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lifetime of Human Visual Sensory Memory: Properties and Neural Substrate Abstract The classic partial-report procedure was modified to optimize the condition to measure the transient decay of visual sensory memory (VSM, also known as iconic memory). A model was developed to isolate the VSM and visual working memory (VWM) underlying the partial-report performance. The decay of VSM in each subject was well characterized by a single exponential function, thus a lifetime could be defined for VSM decay in individual subjects. It was found that intensive practice with partialreport task prolonged VSM lifetime. This practice effect shows an unexpected adaptive property of VSM and reveals VSM lifetime as a specific dimension for perceptual learning. Of the stimulus parameters, a change of the mean luminance of the stimuli from that of the background shortened the VSM lifetime. Such a "luminance effect" is consistent with the temporal properties of the spatial frequency channels in the visual pathway, most likely revealing the differences in the time course of the decay of the memory traces in these channels. -

Unit 7A: Memory

UNIT 7A: MEMORY THE PHENOMENON OF MEMORY ____PROCESSING_____. Some processing requires OBJECTIVE 1: Define memory, and explain how flashbulb effort at first but with ______PRACTICE______ and memories differ from other memories. ____EXPERIENCE_______ it becomes effortless. 1. Learning that persists over time indicates the existence of _____MEMORY___________ for that learning. Give examples of material that is typically encoded with 2. Memories for surprising, significant moments that are little or no effort. especially clear are called _____FLASHBULB______ AUTOMATIC PROCESSING INCLUDES THE ENCODING OF memories. Like other memories, these INFORMATION ABOUT SPACE, TIME, AND FREQUENCY. IT ALSO _______CAN____________ memories (can/cannot) err. INCLUDES THE ENCODING OF WORD MEANING, A TYPE OF ENCODING THAT APPEARS TO BE LEARNED. OBJECTIVE 2: Describe Atkinson-Shiffrin’s classic three- OBJECTIVE 4: Contrast effortful processing with automatic stage processing model of memory, and explain how the processing, and discuss the next-in-line effect, the spacing contemporary model of working memory differs. effect, and the serial position effect. 3. Both human memory and computer memory can be 2. Encoding that requires attention and effort is called viewed as _____INFORMATION_____- ___EFFORTFUL_____ ______PROCESSING_____. ___PROCESSING__________ systems that perform three 3. With novel information, conscious repetition, or tasks: _____ENCODING_______, ______REHEARSAL____, boosts memory. ______STORAGE________, and 4. A pioneering researcher in verbal memory was ___RETRIEVAL____________. ______EBBINGHAUS____. In one experiment, he found 4. The classic model of memory has been Atkinson and that the longer he studied a list of nonsense syllables, Shiffrin’s ________THREE________- the ____FEWER__________ (fewer/greater) the number ________STAGE_________ ______PROCESSING______ of repetitions he required to learn it later. model. According to this model, we first record 5. -

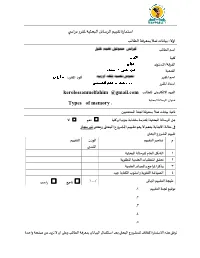

030102162400756Types of Memory

استمارة تقييم الرسائل البحثية ملقرر دراس ي اوﻻ : بيانات تمل بمعرفة الطالب اسم الطالب كلية الفرقة/املستوى الشعبة اسم املقرر كود املقرر: استاذ املقرر البريد اﻻلكترونى للطالب kerolessamuelfahim @gmail.com عنوان الرسالة البحثية Types of memory : ثانيا: بيانات تمل بمعرفة لجنة املمتحنيين هل الرسالة البحثية املقدمة متشابة جزئيا او كليا ☐ نعم ☐ ﻻ فى حالة اﻻجابة بنعم ﻻ يتم تقييم املشروع البحثى ويعتبر غير مجاز تقييم املشروع البحثى م عناصر التقييم الوزن التقييم النسبى 1 الشكل العام للرسالة البحثية 2 تحقق املتطلبات العلمية املطلوبة 3 يذكر املراجع واملصادر العلمية 4 الصياغة اللغوية واسلوب الكتابة جيد نتيجة التقييم النهائى /100 ☐ ناجح ☐ راسب توقيع لجنة التقييم 1. .2 .3 .4 .5 ترفق هذه اﻻستمارة كغﻻف للمشروع البحثى بعد استكمال البيانان بمعرفة الطالب وعلى ان ﻻ تزيد عن صفحة واحدة TYPES of memory Memory , the free Memory is the faculty of the brain by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, it would be impossible for language, relationships, or personal identity to develop. Memory loss is usually described as forgetfulness or amnesia. Memory is often understood as an informational processing system with explicit and implicit functioning that is made up of a sensory processor, short-term (or working) memory, and long- term memory. This can be related to the neuron. The sensory processor allows information from the outside world to be sensed in the form of chemical and physical stimuli and attended to various levels of focus and intent. -

Explain Sperling's Experiments About Sensory Memory. Compare and Contrast the Results of the Whole- Vs

Cognitive Psychology Exam 2 Sample Questions Chapter 5 Material: Explain Sperling's experiments about sensory memory. Compare and contrast the results of the whole- vs. partial-report methods, and use this example to explain how clever experimentation can reveal rapid cognitive processes that we are usually unaware of. This experiment measured the capacity and duration of sensory memory by flashing an array of letters on a screen and asking participants to report as many as possible. When they were asked to report as many as could be seen, using the whole report method, they could only recall 4.5/12 letters. When a tone was added to signify which row to recall using the partial report method, they could report 3.3/4 letters. Explain proactive interference and the release from proactive interference. First, provide experimental evidence for these phenomena. Then, use these two concepts to describe successful strategies for studying in college. George Sperling showed that the perceptual span of 4.5 items was really a limit on a. perception. b. memory. c. processing. d. attention. The three structural components of the modal model of memory are a. receptors, occipital lobe, temporal lobe. b. receptors, temporal lobe, frontal lobe. c. sensory memory, short-term memory, long-term memory. d. sensory memory, iconic memory, rehearsal. When a sparkler is twirled rapidly, people perceive a circle of light. This occurs because a. the trail you see is caused by sparks left behind from the sparkler. b. due to its high intensity, we see the light from the sparkler for about a second after it goes out. -

2012 Program Meeting Schedule

Vision Sciences Society 12th Annual Meeting, May 11-16, 2012 Waldorf Astoria Naples, Naples, Florida Program Contents Board, Review Committee & Staff . 2 Saturday Morning Talks . 33 Featured Events . 3 Saturday Monring Posters. 34 VSS @ ARVO Symposium . 3 Saturday Afternoon Talks . 38 Meeting Schedule . 4 Saturday Afternoon Posters . 39 Schedule-at-a-Glance . 6 Sunday Morning Talks. 43 Poster Schedule . 8 Sunday Morning Posters . 44 Talk Schedule . 10 Sunday Afternoon Talks . 48 Keynote Address . 11 Sunday Afternoon Posters. 49 Elsevier/VSS Young Investigator Award. 12 Monday Morning Talks . 53 Funding Workshops . 13 Monday Morning Posters . 54 Club Vision Dance Party. 13 Tuesday Morning Talks . 58 Satellite Events. 14 Tuesday Morning Posters . 59 Elsevier/Vision Research Travel Awards 15 Tuesday Afternoon Talks . 63 Student Events . 16 Tuesday Afternoon Posters . 64 VSS Public Lecture . 17 Wednesday Morning Talks . 68 Attendee Resources . 18 Wednesday Morning Posters . 69 Exhibitors . 21 Topic Index. 72 VSS Dinner and Demo Night . 24 Author Index . 75 Member-Initiated Symposia . 27 Hotel Floorplan . 91 Friday Evening Posters . 30 Advertisements. 93 Program and Abstracts cover design by Asieh Zadbood, Brain and Cognitive Science Dept., Seoul National University, Psychology Dept., Vanderbilt University T-shirt design and page graphics by Jeffrey Mulligan, NASA Ames Research Center Board, Review Committee & Staff Board of Directors Marisa Carrasco (2013), President Mary Hayhoe (2015) New York University University of Texas, Austin Karl -

The University Seminars University the 2015 Seminars, Speakers, & Topics of Directory

THE2015 UNIVERSITY SEMINARS COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 DIRECTORY OF SEMINARS, SPEAKERS, & TOPICS Contents Introduction . 4 History of the University Seminars . 6 Annual Report . 8 Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lectures Series . 10 Schoff and Warner Publication Awards . 13 Digital Archive Launch . 16 Tannenbaum-Warner Award and Lecture . .. 17 Book Launch and Reception: Plots . 21 2015–2016 Seminar Conferences: Women Mobilizing Memory: Collaboration and Co-Resistance . 22 Joseph Mitchell and the City: A Conversation with Thomas Kunkel And Gay Talese . 26 Alberto Burri: A Symposium at the Italian Academy of Columbia University . 27 “Doing” Shakespeare: The Plays in the Theatre . 28 The Politics of Memory: Victimization, Violence, and Contested Memories of the Past . 30 70TH Anniversary Conference on the History of the Seminar in the Renaissance . .. 40 Designing for Life And Death: Sustainable Disposition and Spaces Of Rememberance in the 21ST Century Metropolis . 41 Calling All Content Providers: Authors in the Brave New Worlds of Scholarly Communication . 46 104TH Meeting of the Society of Experimental Psychologists . 47 From Ebola to Zika: Difficulties of Present and Emerging Infectious Diseases . 50 The Quantitative Eighteenth Century: A Symposium . 51 Appetitive Behavior Festchrift: A Symposium Honoring Tony Sclafani and Karen Ackroff . 52 Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Unreported Struggles: Conflict and Peace . 55 The Power to Move . 59 2015– 2016 Seminars . 60 Index of Seminars . 160 Directory of Seminars, Speakers, & Topics 2015–2016 3 ADVISORY COMMITTEE 2015–2016 Robert E. Remez, Chair Professor of Psychology, Barnard College George Andreopoulos Professor, Political Science and Criminal Justice CUNY Graduate School and University Center Susan Boynton Professor of Music, Columbia University Jennifer Crewe President and Director, Columbia University Press Kenneth T.