Unit 7A: Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dance and the Imagination an Inspiration Turned Into a Fantasy

Twelve Conceptions of Imagination – by Leslie Stevenson (1) The ability to think of something not presently perceived, but spatio‐ temporally real. (2) The ability to think of whatever one acknowledges as possible in the spatio‐temporal world. (3) The ability to think of something that the subject believes to be real, but which is not. (4) The ability to think of things that one conceives of as fictional. (5) The ability to entertain mental images. (6) The ability to think of anything at all. (7) The non‐rational operations of the mind, that is, those explicable in terms of causes rather than reasons. (8) The ability to form perceptual beliefs about public objects in space and time. (9) The ability to sensuously appreciate works of art or objects of natural beauty without classifying them under concepts or thinking of them as useful. (10) The ability to create works of art that encourage such sensuous appreciation. (11) The ability to appreciate things that are expressive or revelatory of the meaning of human life. (12) The ability to create works of art that express something deep about the meaning of life. Dance and the Imagination An inspiration turned into a fantasy based reality A dream envisioned and resourcefully staged Mental creative pictures coming to life Inventiveness using human movement in space Innovation and individuality whether improvised or more formally choreographed Expressive bodily ideas Experiential corporal representations Artistic power and ingenuity transposed into physical form Presentational musculo-skeletal -

Memory & Cognition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Syracuse University Research Facility and Collaborative Environment Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2006 Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make? Donna J. Bridge Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Other Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bridge, Donna J., "Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make?" (2006). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 655. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/655 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory & Cognition: What difference does gender make? Donna J. Bridge Department of Psychology Syracuse University Abstract Small but significant gender differences, typically favoring women, have pre- viously been observed in experiments measuring human episodic memory performance. In three studies measuring episodic memory, we compared performance levels for men and women. Secondary analysis from a paired- associate learning task revealed a superior ability for women to learn single function pairs (i.e. words that are represented in only one pair), but per- formance levels for double function pairs (i.e. pairs that contain words that are also used in one other pair) were similar for men and women. -

Reversible Verbal and Visual Memory Deficits After Left Retrosplenial Infarction

Journal of Clinical Neurology / Volume 3 / March, 2007 Case Report Reversible Verbal and Visual Memory Deficits after Left Retrosplenial Infarction Jong Hun Kim, M.D.*, Kwang-Yeol Park, M.D.†, Sang Won Seo, M.D.*, Duk L. Na, M.D.*, Chin-Sang Chung, M.D.*, Kwang Ho Lee, M.D.*, Gyeong-Moon Kim, M.D.* *Department of Neurology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea †Department of Neurology, Chung-Ang University Medical Center, Chung-Ang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea The retrosplenial cortex is a cytoarchitecturally distinct brain structure located in the posterior cingulate gyrus and bordering the splenium, precuneus, and calcarine fissure. Functional imaging suggests that the retrosplenium is involved in memory, visuospatial processing, proprioception, and emotion. We report on a patient who developed reversible verbal and visual memory deficits following a stroke. Neuro- psychological testing revealed both anterograde and retrograde memory deficits in verbal and visual modalities. Brain diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an acute infarction of the left retrosplenium. J Clin Neurol 3(1):62-66, 2007 Key Words : Retrosplenium, Memory, Amnesia We report on a patient who developed both verbal INTRODUCTION and visual memory deficits after an acute infarction of the retrosplenial cortex. The main structures related to human memory are the Papez circuit, the basolateral limbic circuit, and the basal forebrain, which communicate with each other through white-matter tracts. Damage to these structures (in- cluding the communication tracts) from hemorrhages, infarctions, and tumors can result in memory dis- turbances.1,2 In addition to these structures, Valenstein et al. -

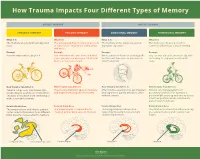

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Webinar Lecture #5

5/20/20 Foundations for Integrating Hypnosis into Your Therapies for Treating Anxiety, Depression, and Pain with Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. Webinar Section 5 of 12 Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 1 • Direct regression to a specific time, context • Imagery of special vehicles • Metaphorical and indirect approaches Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 2 • Orient to hypnosis • Induction • Response set regarding memory • Regression strategy; emphasize positive memory • Interaction (remember to ask neutrally) • PHS (integrate a positive learning from the experience) • Closure and disengagement Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 3 1 5/20/20 •Encoding •Storage •Retrieval Distortions can occur at any stage Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 4 “Memory is reconstructive, not reproductive” Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 5 “I have the feeling…but I don’t have the memory” Stage hypnosis: “What’s so funny about your movie?” Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 6 2 5/20/20 That’s why hypnotically obtained testimony is generally excluded from court proceedings In Search of Memory by Eric Kandel Searching for Memory by Daniel Schacter The Seven Sins of Memory by Daniel Schacter The Memory Illusion by Julia Shaw Memory by Bennett Schwartz Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 8 And a whole new generation of therapists is starting to make some of the same mistakes all over again… Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 9 3 5/20/20 See “Divided Memories,” a PBS 4-hour documentary on the subject you’ll find on YouTube Also watch the demonstration of implanting a false memory on YouTube by Dr. -

Serial Position Effects and Forgetting Curves: Implications in Word

Studies in English Language Teaching ISSN 2372-9740 (Print) ISSN 2329-311X (Online) Vol. 2, No. 3, 2014 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/selt Original Paper Serial Position Effects and Forgetting Curves: Implications in Word Memorization Guijun Zhang1* 1 Department of Foreign Languages, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China * Guijun Zhang, E-mail:[email protected] Abstract Word memorization is important in English learning and teaching. The theory and implications of serial position effects and forgetting curves are discussed in this paper. It is held that they help students understand the psychological mechanisms underlying word memorization. The serial position effects make them to consider the application the chunking theory in word memorization; the forgetting curve reminds them to repeat the words in long-term memory in proper time. Meanwhile the spacing effect and elaborative rehearsal effect are also discussed as they are related to the forgetting curve. Keywords serial position effects, forgetting curves, word memorization 1. Introduction English words are extraordinarily significant for English foreign language (EFL) learners because they are the essential basis of all language skills. As Wilkins said, “...while without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (Wilkins, 1972). Effective word memorization plays a significant role in the process of vocabulary learning. Researchers have and are still pursuing and summarizing the effective memory methods. Schmitt, for example, classified vocabulary memory strategies into more than twenty kinds (Schmitt, 1997, p. 34). However, it is hard to improve the efficiency of the vocabulary memory in that different students remember the huge amount of words with some certain method or methods that may not suit them. -

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

A Critical Skill for Learning Scott Barry Kaufman in Recent Years, Schools

Imagination: A Critical Skill for Learning Scott Barry Kaufman In recent years, schools have become increasingly focused on developing “executive functions” in students. These functions—which include the ability to concentrate, ignore distractions, regulate emotions, and integrate complex information in working memory—are certainly important contributors to learning. However, I believe that in our school’s excitement over executive functions, we’ve missed out on the why of education. Another class of functions have been recently discovered by cognitive neuroscientists that-- when combined with executive functioning—contribute to deep, personally meaningful learning, long-term retention, compassion, and creativity. Dubbed the “default mode network” by cognitive scientists, the following imagination-related functions have been associated with this network: daydreaming, imagining and planning the future, retrieving deeply personal memories, making meaning out of experiences, monitoring one’s emotional state, reading fiction, reflective compassion, and perspective taking. This is an important set of skills to fall by the wayside among our students! In fact, by constantly demanding the executive attention of students for the purposes of abstract learning, we are actively robbing students of the opportunity to use the limited resource of attention for the purposes of personal reflection, meaning-making, and compassionate perspective taking. Let’s be clear: both executive functions and imagination-related cognitive processes are critical to learning. However, when these networks couple together, we can get the best learning outcomes out of students. People who live a meaningful life of creativity and accomplishment combine dreaming with doing. A common thread that runs through both grit and imagination is trial-and-error: the ability to dream, to set concrete goals, to construct various strategies to reach the goal, to tinker with alternative approaches to reaching the goal, and to constantly revise approaches where necessary. -

Kenneth Andrew Norman

Kenneth Norman August 24, 2013 page 1 of 18 Kenneth Andrew Norman Department of Psychology Princeton University Green Hall, Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08540 email: [email protected] work phone: (609) 258-9694 work fax: (609) 258-1113 Employment July 2012 – present Associate Chair Department of Psychology, Princeton University July 2013 – present Professor Department of Psychology and Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Princeton University July 2008 – June 2013 Associate Professor Department of Psychology and Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Princeton University July 2002 – June 2008 Assistant Professor Department of Psychology, Princeton University Education June 1999 Ph.D. in Psychology, Harvard University Advisor: Daniel Schacter, Ph.D. Thesis: "Differential Effects of List Strength on Recollection and Familiarity" June 1996 MA in Psychology, Harvard University June 1993 BS with distinction, Stanford University Advisors: John Gabrieli, Ph.D., Fred Dretske, Ph.D. Honors Thesis: "Is Consciousness the Gatekeeper of Memory?" Additional Education June 1999 – June 2002 NIH NRSA postdoctoral fellow, University of Colorado, Boulder Mentor: Randall O’Reilly, Ph.D. 1995 Fellow, McDonnell Summer Institute in Cognitive Neuroscience, Davis, CA Kenneth Norman August 24, 2013 page 2 of 18 Research Interests Using computational models to explore the neural basis of learning and memory Testing the predictions of these models, using behavioral and neuroimaging measures Developing multivariate methods for extracting information about cognitive states -

Osmosis Study Guide

How to Study in Medical School How to Study in Medical School Written by: Rishi Desai, MD, MPH • Brooke Miller, PhD • Shiv Gaglani, MBA • Ryan Haynes, PhD Edited by: Andrea Day, MA • Fergus Baird, MA • Diana Stanley, MBA • Tanner Marshall, MS Special Thanks to: Henry L. Roediger III, PhD • Robert A. Bjork, PhD • Matthew Lineberry, PhD About Osmosis Created by medical students at Johns Hopkins and the former Khan Academy Medicine team, Os- mosis helps more than 250,000 current and future clinicians better retain and apply knowledge via a web- and mobile platform that takes advantage of cutting-edge cognitive techniques. © Osmosis, 2017 Much of the work you see us do is licensed under a Creative Commons license. We strongly be- lieve educational materials should be made freely available to everyone and be as accessible as possible. We also want to thank the people who support us financially, so we’ve made this exclu- sive book for you as a token of our thanks. This book unlike much of our work, is not under an open license and we reserve all our copyright rights on it. We ask that you not share this book liberally with your friends and colleagues. Any proceeds we generate from this book will be spent on creat- ing more open content for everyone to use. Thank you for your continued support! You can also support us by: • Telling your classmates and friends about us • Donating to us on Patreon (www.patreon.com/osmosis) or YouTube (www.youtube.com/osmosis) • Subscribing to our educational platform (www.osmosis.org) 2 Contents Problem 1: Rapid Forgetting Solution: Spaced Repetition and 1 Interleaved Practice Problem 2: Passive Studying Solution: Testing Effect and 2 "Memory Palace" Problem 3: Past Behaviors Solution: Fogg Behavior Model and 3 Growth Mindset 3 Introduction Students don’t get into medical school by accident. -

Year 12 SELF Cognition Memory

Year 12 SELF Cognition Memory U3ATPSY Except where indicated, this content © Department of Education Western Australia 2020 and released under Creative Commons CC BY NC Before re-purposing any third party content in this resource refer to the owner of that content for permission. Year 12 SELF | Cognition Memory | © Department of Education WA 2020 U3ATPSY Year 12 SELF – Cognition Memory Syllabus points covered: • psychological concepts and processes associated with memory and their relationship to behaviour • multi store model of memory – Atkinson and Shiffrin, 1968 • sensory register o duration, capacity, encoding • short-term memory (working memory) o duration, capacity and encoding o working memory model – Baddeley and Hitch, 1974 • long-term memory o duration, capacity and encoding o procedural memory o declarative memory – semantic and episodic • recall, recognition, re-learning • forgetting: retrieval failure, interference, motivated forgetting, decay. Instructions: Carefully read and make notes on the following material. Complete all activities. Except where indicated, this content © Department of Education Western Australia 2020 and released under Creative Commons CC BY NC Before re-purposing any third party content in this resource refer to the owner of that content for permission. 1 U3ATPSY MEMORY Memory is the organisation, storage and retrieval of information. There are three main ways of measuring what a person has remembered: • recall – retrieving information from memory without prompts • recognition – identifying information from a number of alternatives (recognition is easier than recall – e.g. multiple choice questions easier than short answer questions) • relearning – involves relearning information previously learned. If the information is learned quickly it is assumed that some information has been retained from previous learning. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33).