Amd Inventory in Wv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pohick Creek Watershed Management Plan Are Included in This Section

Watershed Management Area Restoration Strategies 5.0 Watershed Management Area Restoration Strategies The Pohick Creek Watershed is divided into ten smaller watershed management areas (WMAs) based on terrain. Summaries of Pohick Creek’s ten WMAs are listed in the following WMA sections, including field reconnaissance findings, existing and future land use, stream conditions and stormwater infrastructure. For Fairfax County planning and management purposes the WMAs have been further subdivided into smaller subwatersheds. These areas, typically 100 – 300 acres, were used as the basic units for modeling and other evaluations. Each WMA was examined at the subwatershed level in order to capture as much data as possible. The subwatershed conditions were reviewed and problem areas were highlighted. Projects were proposed in problematic subwatersheds. The full Pohick Creek Draft Watershed Workbook, which contains detailed watershed characterizations, can be found in the Technical Appendices. Pohick Creek has four major named tributaries (see Map 3-1.1 in Chapter 3). In the northern portions of the watershed two main tributaries converge into Pohick Creek stream. The Rabbit Branch tributary begins in the highly developed areas of George Mason University and Fairfax City, while Sideburn Branch tributary begins in the highly developed area southwest of George Mason University. The confluence of these two headwater tributaries forms the Pohick Creek main stem. The Middle Run tributary drains Huntsman Lake and moderately-developed residential areas. The South Run tributary drains Burke Lake and Lake Mercer, as well as the low-density southwestern portion of the watershed. The restoration strategies proposed to be implemented within the next ten years (0 – 10-year plan) consist of 90 structural projects. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Base-Flow Yields of Watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia

Base-Flow Yields of Watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia By Ronald D. Evaldi and Katherine S. Paybins Prepared in cooperation with the Berkeley County Commission Data Series 216 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Evaldi, R.D., and Paybins, K.S., 2006, Base-flow yields of watersheds in the Berkeley County Area, West Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 216, 4 p., 1 pl. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

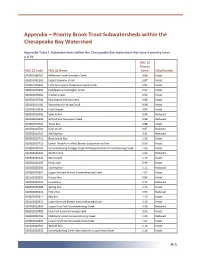

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication was made possible by the support of the following organizations and individuals: Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center West Virginia Assistive Technology System (WVATS) West Virginia Division of Natural Resources West Virginia Division of Tourism Partnerships in Assistive Technologies, Inc. (PATHS) Special thanks to Stephen K. Hardesty and Brittany Valdez for their enthusiasm while working on this Guide. 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 3 • How to Use This Guide ......................................... 4 • ADA Sites .............................................................. 5 • Types of Fish ......................................................... 7 • Traveling in West Virginia ...................................... 15 COUNTY INDEX .......................................................... 19 ACTIVITY LISTS • Public Access Sites ............................................... 43 • Lakes ..................................................................... 53 • Trout Fishing ......................................................... 61 • River Float Trips .................................................... 69 SITE INDEX ................................................................. 75 SITE DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 83 APPENDICES A. Recreation Organizations ......................................207 B. Trout Stocking Schedule .......................................209 -

Class a Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class

Class A Wild Trout Waters Created: August 16, 2021 Definition of Class A Waters: Streams that support a population of naturally produced trout of sufficient size and abundance to support a long-term and rewarding sport fishery. Management: Natural reproduction, wild populations with no stocking. Definition of Ownership: Percent Public Ownership: the percent of stream section that is within publicly owned land is listed in this column, publicly owned land consists of state game lands, state forest, state parks, etc. Important Note to Anglers: Many waters in Pennsylvania are on private property, the listing or mapping of waters by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission DOES NOT guarantee public access. Always obtain permission to fish on private property. Percent Lower Limit Lower Limit Length Public County Water Section Fishery Section Limits Latitude Longitude (miles) Ownership Adams Carbaugh Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Carbaugh Reservoir pool 39.871810 -77.451700 1.50 100 Adams East Branch Antietam Creek 1 Brook Headwaters to Waynesboro Reservoir inlet 39.818420 -77.456300 2.40 100 Adams-Franklin Hayes Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 31 Bedford Bear Run 1 Brook Headwaters to Mouth 40.207730 -78.317500 0.77 100 Bedford Ott Town Run 1 Brown Headwaters to Mouth 39.978611 -78.440833 0.60 0 Bedford Potter Creek 2 Brown T 609 bridge to Mouth 40.189160 -78.375700 3.30 0 Bedford Three Springs Run 2 Brown Rt 869 bridge at New Enterprise to Mouth 40.171320 -78.377000 2.00 0 Bedford UNT To Shobers Run (RM 6.50) 2 Brown -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. -

Fishing Guide

TROUT STOCKING Rivers and Streams Trout Stocking Code No. Stockings .........Period Code No. Stockings .........Period Code No. Stockings .........Period River or Stream: County Code: Area Q One .................... 1st week of March One ................................... February CR Varies .................................... Varies BW South Branch of the Potomac River: W-F: from 0.5 miles north of the Virginia line downstream (about 20 miles) to approximately One .....................................January M One each month .....February-May Pendleton (Franklin Section) 2 miles south of Upper Tract, near the old Poor Farm One every two weeks ..... March-May W Two................................... February MJ One each month ..... January-April South Branch of the Potomac River: One .....................................January Pendleton (Smoke Hole Section) W-F: from U.S. Route 220 bridge downstream to Big Bend Recreation Area One each week .............March-May BA Y One ...........................................April One ........................................ March One................................ The two weeks after Tilhance Creek: Berkeley BW: from one mile below Johnstown upstream 3 miles to state secondary Route 9/7 bridge X After April 1 or area is open to public F Columbus Day week Trout Run: Hardy W: from mouth at Wardensville upstream 7 miles Tuscarora Creek: Berkeley BW: from Martinsburg upstream 5 miles Trout Stocking River or Stream: County Waites Run: Hardy W: from state Route 55 bridge at Wardensville upstream 6.5 miles Code: Area Big Bullskin Run: Jefferson W: from near Wheatland 5 miles downstream to Kabletown Dillons Run: Hampshire BW: from state secondary Route 50/25 bridge upstream 4 miles Evitts Run: Jeferson W-F: from the Charles Town Park upstream to a point 0.5 miles west of town, along state Route 51 W-F: Lost City and Lost River bridges and downstream along state Route 259 to one mile above Lost River: Hardy the U.S. -

2018-Fcps-Honors-Program.Pdf

RECEPTION AND RECOGNITION CEREMONY Wednesday, June 6, 2018 George Mason University Center for the Arts FCPS HONORS 1 2 FAIRFAX COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Schedule of Events | Wednesday, June 6, 2018 Reception 6 p.m. Music Gypsy Jazz Combo West Springfield High School Keith Owens, Director Awards Ceremony 7 p.m. Opening Herndon High School Choir Dana Van Slyke, Director Welcome R Chace Ramey Recognition of the Foundation for Scott Brabrand Fairfax County Public Schools Division Superintendent Remarks on behalf of the Foundation Kevin Reynolds Regional President, Director of Sales, United Bank Chair, Foundation for Fairfax County Public Schools Employee Award Introductions R Chace Ramey Employee Award Presentations Scott Brabrand and Fairfax County School Board and Leadership Team Members Outstanding Elementary New Teacher Outstanding Secondary New Teacher Outstanding New Principal Student Performance Kishan Rao Vocalist, Herndon High School, Senior Employee Award Presentations Continue Outstanding School-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding School-Based Support Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Support Employee Student Performance Allie Lytle Vocalist, Herndon High School, Senior Employee Award Presentations Continue Outstanding School-Based Leader Outstanding Nonschool-Based Leader Outstanding Elementary Teacher Outstanding Secondary Teacher Outstanding Principal Closing Remarks R Chace Ramey FCPS HONORS 3 The Foundation for Fairfax County Public Schools is dedicated to Signature Sponsor recognizing and celebrating the accomplishments and contributions of FCPS employees through the annual FCPS Honors event. Our Mission The Foundation for FCPS seeds strategic initiatives of FCPS that will engage and inspire students to thrive. Highest Honors Sponsor Our Initiatives State of Education Luncheon, November, 2018 Teacher Grants Program, launched May, 2018. -

SLEEPY CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT Morgan County, WV

SLEEPY CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT Morgan County, WV Sponsored by: Sleepy Creek Watershed Association USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Eastern Panhandle Conservation District Shepherd University March 2006 Acknowledgements: The Sleepy Creek Watershed Association is indebted to Shepherd University’s Institute for Environmental Studies, the Eastern Panhandle Conservation District, the West Virginia Conservation Agency, West Virginia Division of Forestry, and the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service for their assistance with this study. The work and guidance of these institutions and agencies were invaluable in carrying out the investigations and compiling data that went into this report. Principal authors: Holly Boyer, Shepherd University Wendy Lee Maddox, Shepherd University Gale Foulds, Sleepy Creek Watershed Association Rebecca MacLeod, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Herb Peddicord, WV Division of Forestry Additional assistance: Barbara Elliott, West Virginia Conservation Agency Dr. Ed Snyder, Shepherd University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 WATERSHED AREA........................................................................................................ 6 Major Tributaries ......................................................................................................... -

Appendix D: Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) – Jan 2015

Appendix D: Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) – Jan 2015 Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - Jan 2015 Lower Lower Length County Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Limit Lat Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Marsh Creek Not Recorded Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 7.91 Armstrong Bullock Run North Fork Pine Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.879723 -79.441391 1.81 Armstrong Cornplanter Run Buffalo Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.754444 -79.671944 1.76 Armstrong Crooked Creek Allegheny River Headwaters to conf Pine Rn 40.722221 -79.102501 8.18 Armstrong Foundry Run Mahoning Creek Lake Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.910416 -79.221046 2.43 Armstrong Glade Run Allegheny River Headwaters dnst to second trib upst from mouth 40.767223 -79.566940 10.51 Armstrong Glade Run Mahoning Creek Lake Headwaters