A New Modular Approach to the Composition of Film Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies

Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies Beginnings and Endings in Films, Film and Film Studies, University of Warwick, 13th June 2008 A report by Martin Zeller, University of York, UK This conference, organised by Tom Hughes and James MacDowell (both of University of Warwick), examined the beginnings and endings of individual films and structures of beginnings and endings in films more generally, as well as notions of beginning and ending in film studies as a discipline. With such a wide remit it is not surprising that links between the various presentations were sometimes difficult to establish. However, the wide variety of approaches to the topic ensured lively discussions. The tone for the day was set by the keynote paper delivered by Warwick's own V. F. Perkins. Examining beginnings and endings in the genre of 'multi-story' (or portmanteau) movies, Perkins elucidated the various methods used to make the author the focus of these multi-stranded narratives. Drawing on the literary cachet of their source texts, Quartet, Full House and Le Plaisir make Maugham, O. Henry and Maupassant the respective loci around which their stories revolve. Pointing out that authorial intrusions were, with the exception of Le Plaisir, used only at the beginnings of such films, Perkins suggested the possibility of a largely unexplored narrative technique available in returning to the author at the close of a film. However, it was Professor Perkin's call for, 'an aesthetics of the quite good, of the satisfactorily effective, as well as the extremes: the abject and the sublime,' that seemed to resonate most with the delegates and to become a touchstone for the day's later discussions. -

Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’

Aditya Hans Prasad WGSS 07 Professor Douglas Moody April 2018. Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’ Released in 1979, director Ridley Scott’s film Alien is renowned as one of the few science fiction films that surpasses most horror films in its power to terrify an audience. The film centers on the crew of the spaceship ‘Nostromo’, and how the introduction of an unknown alien life form wreaks havoc on the ship. The eponymous Alien individually murders each member of the crew, aside from the primary antagonist Ripley, who manages to escape. Interestingly, the film uses subtle representations of motherhood in order to create a truly scary effect. These representations are incredibly interesting to study, as they tie in to various existing archetypes surrounding motherhood and the concept of the ‘monstrous feminine’. In her essay ‘Alien and the Monstrous Feminine’, Barbara Creed discusses the various notions that surround motherhood. First, she writes about the “ancient archaic figure who gives birth to all living things” (Creed 131). Essentially, she discusses the great mother figures of the mythologies of different cultures—Gaia, Nu Kwa, Mother Earth (Creed 131). These characters embody the concept that mothers are nurturing, loving, and caring. Traditionally, stories, films, and other forms of material reiterate and r mothers in this nature. However, there are many notable exceptions to this representation. For example, the primary antagonist in many Brothers Grimm stories are the evil step-mother, a character completely devoid of the maternal warmth and nurturing character of the traditional mother. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Kali is worshipped as the mother of the universe. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and The

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

The Art of David Lynch

The Art of David Lynch weil das Kino heute wieder anders funktioniert; für ei- nen wie ihn ist da kein Platz. Aber deswegen hat Lynch ja nicht seine Kunst aufgegeben, und nicht einmal das Filmen. Es ist nur so, dass das Mainstream-Kino den Kaperversuch durch die Kunst ziemlich fundamental abgeschlagen hat. Jetzt den Filmen von David Lynch noch einmal wieder zu begegnen, ist ein Glücksfall. Danach muss man sich zum Fernsehapparat oder ins Museum bemühen. (Und grimmig die Propaganda des Künstlers für den Unfug transzendentaler Meditation herunterschlucken; »nobody is perfect.«) Was also ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Seine Arbeit geschah und geschieht nach den »Spielregeln der Kunst«, die bekanntlich in ihrer eigenen Schöpfung und zugleich in ihrem eigenen Bruch bestehen. Man er- kennt einen David-Lynch-Film auf Anhieb, aber niemals David Lynch hat David Lynch einen »David-Lynch-Film« gedreht. Be- 21 stimmte Motive (sagen wir: Stehlampen, Hotelflure, die Farbe Rot, Hauchgesänge von Frauen, das industrielle Rauschen, visuelle Americana), bestimmte Figuren (die Frau im Mehrfachleben, der Kobold, Kyle MacLachlan als Stellvertreter in einer magischen Biographie - weni- ger, was ein Leben als vielmehr, was das Suchen und Was ist das Besondere an David Lynch? Abgesehen Erkennen anbelangt, Väter und Polizisten), bestimmte davon, dass er ein paar veritable Kultfilme geschaffen Plot-Fragmente (die nie auflösbare Intrige, die Suche hat, Filme, wie ERASERHEAD, BLUE VELVET oder die als Sturz in den Abgrund, die Verbindung von Gewalt TV-Serie TWIN PEAKS, die aus merkwürdigen Gründen und Design) kehren in wechselnden Kompositionen (denn im klassischen Sinn zu »verstehen« hat sie ja nie wieder, ganz zu schweigen von Techniken wie dem jemand gewagt) die genau richtigen Bilder zur genau nicht-linearen Erzählen, dem Eindringen in die ver- richtigen Zeit zu den genau richtigen Menschen brach- borgenen Innenwelten von Milieus und Menschen, der ten, und abgesehen davon, dass er in einer bestimmten Grenzüberschreitung von Traum und Realität. -

Bmus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2

BMus 1 Analysis: Week 9 1 BMus 1 Analysis Week 9 Project 2 Just to remind you: the second project for this module is an essay (c. 1500 words) on one short post-tonal work from the list below. All of the works can be found in the library; if they’re not available for any reason, ask me for a copy. (Most can be found online as well.) Béla Bartók, 44 Duos for Violin, no. 33: ‘Erntelied’ (‘Harvest Song’) Harrison Birtwistle, Duets for Storab, any two movements Ruth Crawford-Seeger, String Quartet, movt. 2: ‘Leggiero’ or movt. 3: ‘Andante’ György Kurtag, Játékok Book 6, ‘In memoriam András Mihály’ Elisabeth Lutyens, Présages op. 53, theme and variations 1-2. Olivier Messiaen, Préludes, no. 1: ’La Colombe’ Kaija Saariaho, Sept Papillons, movements 1 and 2 Arnold Schoenberg, 6 Little Piano Pieces, Op.19: No. 2 (Langsam) Igor Stravinsky, 3 pieces for String Quartet, no. 1 Anton Webern, Variations op 27: no. 2 What to cover You may format your essay as you wish, according to what best suits the piece you’ve selected. However, you should aim to comment on the following (interrelated) features of your chosen work: • Formal Design o How is this articulated? This may involve pitch / tempo / changes of texture / dynamics / phrasing and other musical features. • Pitch Structure o Use of interval / mode(s) / pitch sets / 12-note chords and other techniques • Nature and Handling of Melodic and Harmonic Materials o How is the material constructed, treated, developed and/or elaboration in the work? Do not forget the importance of rhythm as well as pitch. -

Knowledge Organiser

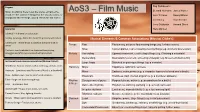

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

WITH OUR DEMONS a Thesis Submitted By

1 MONSTROSITIES MADE IN THE INTERFACE: THE IDEOLOGICAL RAMIFICATIONS OF ‘PLAYING’ WITH OUR DEMONS A Thesis submitted by Jesse J Warren, BLM Student ID: u1060927 For the award of Master of Arts (Humanities and Communication) 2020 Thesis Certification Page This thesis is entirely the work of Jesse Warren except where otherwise acknowledged. This work is original and has not previously been submitted for any other award, except where acknowledged. Signed by the candidate: __________________________________________________________________ Principal Supervisor: _________________________________________________________________ Abstract Using procedural rhetoric to critique the role of the monster in survival horror video games, this dissertation will discuss the potential for such monsters to embody ideological antagonism in the ‘game’ world which is symptomatic of the desire to simulate the ideological antagonism existing in the ‘real’ world. Survival video games explore ideology by offering a space in which to fantasise about society's fears and desires in which the sum of all fears and object of greatest desire (the monster) is so terrifying as it embodies everything 'other' than acceptable, enculturated social and political behaviour. Video games rely on ideology to create believable game worlds as well as simulate believable behaviours, and in the case of survival horror video games, to simulate fear. This dissertation will critique how the games Alien:Isolation, Until Dawn, and The Walking Dead Season 1 construct and themselves critique representations of the ‘real’ world, specifically the way these games position the player to see the monster as an embodiment of everything wrong and evil in life - everything 'other' than an ideal, peaceful existence, and challenge the player to recognise that the very actions required to combat or survive this force potentially serve as both extensions of existing cultural ideology and harbingers of ideological resistance across two worlds – the ‘real’ and the ‘game’. -

Edinburgh International Festival 1962

WRITING ABOUT SHOSTAKOVICH Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Edinburgh Festival 1962 working cover design ay after day, the small, drab figure in the dark suit hunched forward in the front row of the gallery listening tensely. Sometimes he tapped his fingers nervously against his cheek; occasionally he nodded Dhis head rhythmically in time with the music. In the whole of his productive career, remarked Soviet Composer Dmitry Shostakovich, he had “never heard so many of my works performed in so short a period.” Time Music: The Two Dmitrys; September 14, 1962 In 1962 Shostakovich was invited to attend the Edinburgh Festival, Scotland’s annual arts festival and Europe’s largest and most prestigious. An important precursor to this invitation had been the outstanding British premiere in 1960 of the First Cello Concerto – which to an extent had helped focus the British public’s attention on Shostakovich’s evolving repertoire. Week one of the Festival saw performances of the First, Third and Fifth String Quartets; the Cello Concerto and the song-cycle Satires with Galina Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich. 31 DSCH JOURNAL No. 37 – July 2012 Edinburgh International Festival 1962 Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya in Edinburgh Week two heralded performances of the Preludes & Fugues for Piano, arias from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies, the Third, Fourth, Seventh and Eighth String Quartets and Shostakovich’s orches- tration of Musorgsky’s Khovanschina. Finally in week three the Fourth, Tenth and Twelfth Symphonies were per- formed along with the Violin Concerto (No. 1), the Suite from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Three Fantastic Dances, the Cello Sonata and From Jewish Folk Poetry. -

David Cronenberg Et Howard Shore. Bref Portrait D'une Longue

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 00:20 Revue musicale OICRM David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration Solenn Hellégouarch Une relève Résumé de l'article Volume 2, numéro 2, 2015 Après 45 ans de carrière, la filmographie de David Cronenberg compte 22 films, dont 15 ont été musicalisés par Howard Shore, qui a rejoint l’équipe du URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060132ar cinéaste en 1979. Si l’univers cronenbergien est aujourd’hui bien connu, DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar l’apport de son compositeur demeure peu exploré. Or, la musique semble y jouer un rôle de toute première importance, le compositeur étant impliqué très Aller au sommaire du numéro tôt dans le processus cinématographique. Cette implication précoce est indicatrice du rôle central qu’occupent Shore et sa musique : comment le définir ? Plutôt que de recourir à une analyse des fonctions de la musique au cinéma, cet article explore les processus de création qui lui donnent naissance. Éditeur(s) Cronenberg et Shore, qui ont « tout appris en commun », présentent ainsi des OICRM processus créateurs aux traits similaires, ou plus exactement des figures artistiques communes, ici exposées, les regroupant sous une seule vision artistique : l’autodidacte, l’expérimentateur, l’improvisateur, le ISSN peintre/sculpteur et l’artiste-artisan. 2368-7061 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Hellégouarch, S. (2015). David Cronenberg et Howard Shore. Bref portrait d’une longue collaboration. Revue musicale OICRM, 2(2), 96–114. https://doi.org/10.7202/1060132ar Tous droits réservés © Revue musicale OICRM, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

Brief for Petitioners

No. 20-315 In the Supreme Court of the United States JOSE SANTOS SANCHEZ AND SONIA GONZALEZ, PETITIONERS, v. ALEJANDRO N. MAYORKAS, SECRETARY, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS LISA S. BLATT JAIME W. APARISI AMY MASON SAHARIA Counsel of Record A. JOSHUA PODOLL YUSUF R. AHMAD MICHAEL J. MESTITZ DANIELA RAAYMAKERS ALEXANDER GAZIKAS APARISI LAW DANIELLE J. SOCHACZEVSKI 819 Silver Spring Avenue WILLIAMS & CONNOLLY LLP Silver Spring, MD 20910 725 Twelfth Street, N.W. (301) 562-1416 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] (202) 434-5000 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether, under 8 U.S.C. § 1254a(f)(4), a grant of Temporary Protected Status authorizes eligible nonciti- zens to obtain lawful-permanent-resident status under 8 U.S.C. § 1255. (I) II PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioners are Jose Santos Sanchez and Sonia Gon- zalez. Respondents are Alejandro N. Mayorkas, Secre- tary, United States Department of Homeland Security; Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Ser- vices; Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Services Nebraska Service Center; and District Director, United States Citizenship & Immigration Services New- ark. III TABLE OF CONTENTS Page OPINIONS BELOW ........................................................... 1 JURISDICTION ................................................................. 2 STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED ..................... 2 STATEMENT .....................................................................