There Are Four Major Forms of Traditional Japanese Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander It is a truth universally acknowledged that the plays of Menander owe a great debt to Classical Athenian drama: connections between plays such as Aristophanes’ Cocalus and Menander were noted in didascalia, and similarly the thematic and structural similarities between New Comedy and the works of Euripides were already recognized in Hellenistic scholarship (Arnott 1972; Csapo 2000; Hunter 2011). Sophocles, on the other hand, is rarely included in this discussion of dramatic influence, more often regarded solely for his role as the pinnacle of tragic poets. It is the purpose of this paper to reanalyze possible connections between the corpus of Sophocles and that of Menander by examining both the Antigone and the Dyscolus as plays employing one of the most familiar stock characters of ancient comedy: the “blocking” father figure. This father figure—whose earliest incarnation arguably belongs to Old Comedy, such as Strepsiades from Clouds—is perhaps best known for his characterization in the plays of Greek New Comedy and their later, Latin iterations. Generally an old and intransigent father, the “blocking” figure is generically defined by his interference in the life of his young offspring; in New Comedy, this interference takes the form of intervention in the budding romance of two young lovers, whose inconvenient marriage will inevitably bring about the typical finale. This character, at first glance, may appear to be a creature created solely for light-hearted drama. Creon of the Antigone, however, whose stubborn and belligerent character has been carefully surveyed for his role within the tragedy itself (see Roisman 1996), additionally shares many features with the father of Menander’s only intact play, Knemon of the Dyscolus. -

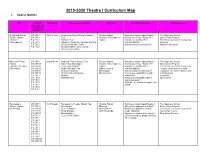

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I. Course Outline Unit Current Timeframe Assessments/Activities Big Idea Essential Questions Core Resources Arkansas SS Framework Alignment Greek and Roman CR.1.TH.1 1st 9 Weeks Greeks and Roman Theatre History Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School Theatre History P.4.THI.2 Test Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character P.4.THI.3 Antigone Test Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Development P.4.THI.5 Napoleon Dynamite Character Analysis characterization? Antigone P.5.THI.2 Life Size Character Poster How do characters affect plot? Napoleon Dynamite P.6.THI.2 Character Observation Journal Greek Theatre Mask Medieval Theatre CR.1.TH.1 2nd 9 Weeks Medieval Theatre History Test Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School History CR.2.THI.1 Solo Acting Monologue Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character Creation CR.2.THI.2 Theme Assessment Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Solo Acting CR.1.THI.3 Modern Morality Play Acting Theories characterization? Veggies Tales used as modern CR.1.THI.4 Character Analysis Monologues How do characters affect plot? (examples of mystery, miracle, and CR.3.THI.1 Character Design Morgue Memorization How do you establish believable morality plays) P.5.THI.1 Audition characters? Everyman P.5.THI.2 Self Reflection How does memorization affect Monologues P.5.THI.4 characterization? P.5.THI.5 -

Baltimore Symphony Open Rehearsals

Baltimore Symphony Open Rehearsals Thank you for your interest to attend the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) Open Rehearsal series for students at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. The BSO Open Rehearsal series is an incredible opportunity to listen in to a working rehearsal of a professional symphony orchestra. This is a fantastic experience for young musicians (HS, MS, & college) to hear the process of the orchestra and conductor as they prepare for a performance. It can provide valuable insight for students who are already classical music lovers and performers. Each rehearsal is 2.5 hours, with a 20-minute break, about half-way through the rehearsal. The conductor may opt to stop and start the music. Some pieces may not be played in their entirety, and some pieces may be skipped altogether. Oftentimes, when the conductor stops, there will be dialogue between the conductor and the musicians, or between the musicians. Unfortunately, this dialogue is often difficult to hear in the audience. We suggest reviewing rehearsal/concert etiquette with your students before arriving at the hall. Any distractions are very disruptive to the musicians on stage and jeopardize our ability to offer this exclusive opportunity to students in the future. While an incredibly meaningful experience for some, it may not be the ideal listening experience for everyone. It is first and foremost a working rehearsal for the orchestra and offers observers a window into that experience with professionals. Younger students or students without a music background are strongly encouraged to attend the BSO’s Midweek series. The Midweek Concerts are curated performances specifically designed for students, and provide a welcoming, inviting, and encouraging way to experience a symphony orchestra. -

Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music

The Institute for Japanese Cultural Heritage Initiatives (Formerly the Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies) and the Columbia Music Performance Program Present Our 8th Season Concert To Celebrate the Institute’s th 45 Anniversary Glories of the Japanese Music Heritage ANCIENT SOUNDSCAPES REBORN Japanese Sacred Gagaku Court Music and Secular Art Music Featuring renowned Japanese Gagaku musicians and New York-based Hōgaku artists With the Columbia Gagaku and Hōgaku Instrumental Ensembles of New York Friday, March 8, 2013 at 8 PM Miller Theatre, Columbia University (116th Street & Broadway) Join us tomorrow, too, at The New York Summit The Future of the Japanese Music Heritage Strategies for Nurturing Japanese Instrumental Genres in the 21st-Century Scandanavia House 58 Park Avenue (between 37th and 38th Streets) Doors open 10am Summit 10:30am-5:30pm Register at http://www.medievaljapanesestudies.org Hear panels of professional instrumentalists and composers discuss the challenges they face in the world of Japanese instrumental music in the current century. Keep up to date on plans to establish the first ever Tokyo Academy of Japanese Instrumental Music. Add your voice to support the bilingual global marketing of Japanese CD and DVD music masterpieces now available only to the Japanese market. Look inside the 19th-century cultural conflicts stirred by Westernization when Japanese instruments were banned from the schools in favor of the piano and violin. 3 The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies takes on a new name: THE INSTITUTE FOR JAPANESE CULTURAL HERITAGE INITIATIVES The year 2013 marks the 45th year of the Institute’s founding in 1968. We mark it with a time-honored East Asian practice— ―a rectification of names.‖ The word ―medieval‖ served the Institute well during its first decades, when the most pressing research needs were in the most neglected of Japanese historical eras and disciplines— early 14th- to late 16th-century literary and cultural history, labeled ―medieval‖ by Japanese scholars. -

Unpacking the Rehearsal Practices of Theatre Professionals and the Significance for the Teaching of Reading and Writing

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2001 It's not as thick as it looks: Unpacking the rehearsal practices of theatre professionals and the significance for the teaching of reading and writing Dale Lorraine Wright University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Wright, Dale Lorraine, "It's not as thick as it looks: Unpacking the rehearsal practices of theatre professionals and the significance for the teaching of eadingr and writing" (2001). Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts Leah Zuidema

Language Arts Journal of Michigan Volume 29 Article 9 Issue 2 Location, Location, Location 4-2014 Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts Leah Zuidema Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lajm Recommended Citation Zuidema, Leah (2014) "Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts," Language Arts Journal of Michigan: Vol. 29: Iss. 2, Article 9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.2013 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language Arts Journal of Michigan by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRACTICE Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts LEAH A. ZUIDEMA ne of the greatest challenges that could help them in visualizing the taken place in somewhat crowded class- of teaching plays in English action of the play. This is problematic, rooms, typically with about 35 students Olanguage arts courses is the as the cognitive work of visualization per section and little room to move fact that scripts are intended for the is a stepping stone to comprehension: about. The lesson sequence continues stage, not the page. While the plots, practiced readers use visualization to to evolve each year with small changes themes, and dialogue of the best scripts help them understand, make connec- and additions, often inspired by stu- are ripe for intensive literary study, care- tions with, and interpret literary texts dents’ suggestions about “what else” we ful attention to dramatic elements— (Wilhelm, 2008). -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

Stage Manager & Assistant Stage Manager Handbook

SM & ASM HANDBOOK Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre STAGE MANAGER & ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER HANDBOOK December 12, 2008 Proposed changes and updates to the Producer Handbook can be submitted in writing or by email to the General Manager. The General Manager and Active Production Chair will enter all approved changes. VTG SM HANDBOOK: December 12, 2008 1 SM & ASM HANDBOOK Stage Manager & Assistant SM Handbook CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. AUDITIONS a) Pre-Audition b) Auditions and Callbacks c) Post Auditions / Pre First Rehearsal 3. REHEARSALS a) Read Through / First Rehearsal b) Subsequent Rehearsals c) Moving to the Mainstage 4. TECH WEEK AND WEEKEND 5. PERFORMANCES a) The Run b) Closing and Strike 6. SM TOOLS & TEMPLATES 1. Scene Breakdown Chart 2. Rehearsal Schedule 3. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Guidelines for Stage Management 4. The Prompt Book VTG SM HB: December 12, 2008 2 SM & ASM HANDBOOK 5. Production Technical Requirements 6. Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 7. Rehearsal Attendance Sheet 8. Stage Management Kit 9. Sample Blocking Notes 10. Rehearsal Report 11. Sample SM Production bulletins 12. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals on Mainstage – SM Guidelines 13. Rehearsals on the Mainstage – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 14. Sample Preset & Scene Change Schedule 15. Performance Attendance Sheet 16. Stage Crew Guidelines and Information Sheet 17. Sample Prompt Book Cues 18. Use of Theatre during Performances – SM Guidelines 19. Sample Production Information Sheet for FOH & Bar 20. Sample SM Preshow Checklist 21. Sample SM Intermission Checklist 22. SM Post Show Checklist 23. -

![E.F. Rhythm Section & Ensemble Setup[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9789/e-f-rhythm-section-ensemble-setup-2-1229789.webp)

E.F. Rhythm Section & Ensemble Setup[2]

The Rhythm Section: Basics All players are “timekeepers” Each instrument needs to know its role & typical function Flexibility to function as part of a combo or a big band In general, the rhythm section dynamics are the cornerstone for the ensemble Use proper rhythm section set-up to facilitate eye/ ear contact for all As always, listening is important, not only for solos, but also the art of comping Rhythm Section: Set-up Trumpets… Amp Trombones... Amp Saxophones… The Rhythm Section: Piano Basics Reading parts & chord symbols Provide harmony, color, rhythmic interest All chords on the chart are not necessarily meant to be played all the time Generally speaking, do not use the pedal, unless indicated or for specific sustain use Piano establishes rhythm section volume The Rhythm Section: Piano Comping Avoid root position chords, use shell voicings at first, for example: • Voicing chords using 3rd and 7th in l.h. • Adding root, fifth, root (roots & fifths are optional) or use color tone substitutions (9 or 6) in r.h. • Open voicings that span over an octave • Generally, stay within an octave of middle C • Move from chord to chord as efficiently as possible Leave space for ensemble and soloist Begin with pre-conceived rhythmic patterns that are idiomatic, then devise your own The Rhythm Section: Piano Players for Comping Red Garland Herbie Hancock Chick Corea Bill Evans Duke or Count Wynton Kelly McCoy Tyner The Rhythm Section: Basic Bass Establish rhythm (groove), time, and harmony Reading parts & chord symbols Pulse vs. feel or tempo vs. -

Nora's Performance in China

Nora’s Performance in China (1914-2010): Inspiration, Communities and Political Theatre By Xiaofei Chen Master thesis Center for Ibsen Studies UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Spring semester, 2010 Acknowledgements I came to Oslo University by serendipity. When I was searching the resources for my thesis Nora’s rewriting in China(1914-1948), by accident the website of Ibsen Center jumped out. Then I came to Norway and studied at Ibsen Center. Whether in Norway or in China, many people asked me why I had chosen Ibsen studies and had come to Norway. I always said because I liked Ibsen’s plays and Norway has an Ibsen Center. It turned out that I had chosen correctly. At the Ibsen Center, professors and students from all over the world gave me lots of chances to access different ideas and insights into Ibsen studies, especially from theatre and performance aspects. I could access the original Ibsen’s texts and understand Norwegian society in Ibsen’s times, and I could watch Ibsen’s performances from different countries either in the National Theatre or through DVDs in class. Thanks to Ibsen Center for giving me the opportunity to study here, and I also want to show my appreciation for all the professors at the Ibsen Center: especially Frode Helland, Astrid Sæther, Jon Nygaard, Atle Kittang, Erika Fischer-Lichte and Nilu Kamaluddin, Julie Holledge, Knut Brynhildsvoll, who gave me the latest information about Ibsen studies through lectures and seminars. My special thanks for my professor, Jon Nygaard, who gave me the inspiration to write this topic with fresh insight. -

Asian-American Media Skills Handbook. INSTITUTION Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Md

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 261 099 UD 024 382 AUTHOR Haines, Roberta M., Comp. TITLE Asian-American Media Skills Handbook. INSTITUTION Montgomery County Public Schools, Rockville, Md. PUB DATE 84 NOTE 107p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) -- Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Americans; Class Activities; Cultural Activities; *Cultural Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Evaluation Criteria; Geography Instruction; Information Sources; Learning Activities; Library Skills; Map Skills; *Skill Development IDENTIFIERS *Asia; Maryland (Montgomery County); *Media Skills ABSTRACT This handbook is for teachers to use in the classroom and as a reference source for information about Asia and Asian-Americans. The handbook uses information about geography and culture to teach skills such as almanac, atlas, and encyclopediause. Other student exercises include: how to sequence a Chinese fairy tale and present it to the class, how to research a Chinese holiday using various reference sources and how to plan its celebration, and how to give a slide presentation using Asian subject matter. The handbook includes a guide to evaluation of materials about Asian-Americans,a list of the countries included in the category "Asia," anda listing of Asian embassies, information services, and organizations in the United States. The handbook closes with listings of the artifacts contained in a "Chinese'Traveling Trunk" and a "New Americans Traveling Trunk," available on loan to district teachers foruse in enhancing understanding of Asian culture. There is alsoa 20 page bibliography arranged by country. (CG) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document.