Tau (Or No) Leptons in Top Quark Decays at Hadron Colliders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decays of the Tau Lepton*

SLAC - 292 UC - 34D (E) DECAYS OF THE TAU LEPTON* Patricia R. Burchat Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University Stanford, California 94305 February 1986 Prepared for the Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC03-76SF00515 Printed in the United States of America. Available from the National Techni- cal Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161. Price: Printed Copy A07, Microfiche AOl. JC Ph.D. Dissertation. Abstract Previous measurements of the branching fractions of the tau lepton result in a discrepancy between the inclusive branching fraction and the sum of the exclusive branching fractions to final states containing one charged particle. The sum of the exclusive branching fractions is significantly smaller than the inclusive branching fraction. In this analysis, the branching fractions for all the major decay modes are measured simultaneously with the sum of the branching fractions constrained to be one. The branching fractions are measured using an unbiased sample of tau decays, with little background, selected from 207 pb-l of data accumulated with the Mark II detector at the PEP e+e- storage ring. The sample is selected using the decay products of one member of the r+~- pair produced in e+e- annihilation to identify the event and then including the opposite member of the pair in the sample. The sample is divided into subgroups according to charged and neutral particle multiplicity, and charged particle identification. The branching fractions are simultaneously measured using an unfold technique and a maximum likelihood fit. The results of this analysis indicate that the discrepancy found in previous experiments is possibly due to two sources. -

J = Τ MASS Page 1

Citation: P.A. Zyla et al. (Particle Data Group), Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 083C01 (2020) J 1 τ = 2 + + τ discovery paper was PERL 75. e e− → τ τ− cross-section threshold behavior and magnitude are consistent with pointlike spin- 1/2 Dirac particle. BRANDELIK 78 ruled out pointlike spin-0 or spin-1 particle. FELDMAN 78 ruled out J = 3/2. KIRKBY 79 also ruled out J=integer, J = 3/2. τ MASS VALUE (MeV) EVTS DOCUMENT ID TECN COMMENT 1776..86 0..12 OUR AVERAGE ± +0.10 1776.91 0.12 1171 1 ABLIKIM 14D BES3 23.3 pb 1, Eee = ± 0.13 − cm − 3.54–3.60 GeV 1776.68 0.12 0.41 682k 2 AUBERT 09AK BABR 423 fb 1, Eee =10.6 GeV ± ± − cm 1776.81+0.25 0.15 81 ANASHIN 07 KEDR 6.7 pb 1, Eee = 0.23 ± − cm − 3.54–3.78 GeV 1776.61 0.13 0.35 2 BELOUS 07 BELL 414 fb 1 Eee =10.6 GeV ± ± − cm 1775.1 1.6 1.0 13.3k 3 ABBIENDI 00A OPAL 1990–1995 LEP runs ± ± 1778.2 0.8 1.2 ANASTASSOV 97 CLEO Eee = 10.6 GeV ± ± cm . +0.18 +0.25 4 Eee . 1776 96 0.21 0.17 65 BAI 96 BES cm= 3 54–3 57 GeV − − 1776.3 2.4 1.4 11k 5 ALBRECHT 92M ARG Eee = 9.4–10.6 GeV ± ± cm +3 6 Eee 1783 4 692 BACINO 78B DLCO cm= 3.1–7.4 GeV − We do not use the following data for averages, fits, limits, etc. -

Search for Rare Multi-Pion Decays of the Tau Lepton Using the Babar Detector

SEARCH FOR RARE MULTI-PION DECAYS OF THE TAU LEPTON USING THE BABAR DETECTOR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ruben Ter-Antonyan, M.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Richard D. Kass, Adviser Klaus Honscheid Adviser Michael A. Lisa Physics Graduate Program Junko Shigemitsu Ralph von Frese ABSTRACT A search for the decay of the τ lepton to rare multi-pion final states is performed + using the BABAR detector at the PEP-II asymmetric-energy e e− collider. The anal- 1 ysis uses 232 fb− of data at center-of-mass energies on or near the Υ(4S) resonance. + 0 In the search for the τ − 3π−2π 2π ν decay, we observe 10 events with an ex- ! τ +2:0 pected background of 6:5 1:4 events. In the absence of a signal, we calculate the − + 0 6 decay branching ratio upper limit (τ − 3π−2π 2π ν ) < 3:4 10− at the 90 % B ! τ × confidence level. This is more than a factor of 30 improvement over the previously established limit. In addition, we search for the exclusive decay mode τ − 2!π−ν ! τ + 0 +1:0 with the further decay of ! π−π π . We observe 1 event, expecting 0.4 0:4 back- ! − 7 ground events, and calculate the upper limit (τ − 2!π−ν ) < 5:4 10− at the B ! τ × 90 % confidence level. This is the first upper limit for this mode. -

Detection of the Tau-Neutrino at The

DETECTION OF THE TAIPNEIITRINO AT me LI·IC* Klaus Winter CERN. Geneva. Switzerland I. Introduction Following the discovery of the tau-lepton in e+e` collisions by M. Perl and collabo rators [1 ], all evidence today favours the hypothesis that it is a sequential heavy lepton belonging to a third lepton Family [2]. From measurements of the forward-bacl< ward angular asymmetry of tau produced in e+e` annihilations [3], [4] e+e* +* ft a value of the axial-vector neutral current coupling constant of ga = — 0.—l5 1 0.05 was deduced in agreement with ga = -1 /2 for the assignment of lel’t—handed tau leptons as the "down" state (I3 = -1 /2) of a weak isospin doublet. Hence, the most natural assignment of the "up" state (I3 = +1/2) would be to a neutrino with the same lepton flavour. the tau-neutrino. Further indirect evidence about the tau—neutrino can be obtained from leptonic tau decays [4]. e.g. 1:- Q u_v,,X. The muon energy spectrum has the familiar [2] Michel shape suggesting that the par ticle X is a spin l /2 particle. Its mass has been constrained to less than 35 MeV by analysing semi-leptonic tau—deca)s with multipion final states [5]. Hence, the particle Xmay be a neutrino. Is it a sequential neutrino, with a flavour property which distin guishes it from the electron- and the muon-neutrino? The possibility of a complete identity with we or uu can indeed be excluded. Searches for charged current neutrino reactions which produce a tau-lepton UN ·=* T_X have given negative results. -

Physics with Tau Lepton Final States in ATLAS

EPJ Web of Conferences 49, 18022 (2013) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/ 20134918022 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2013 Physics with Tau Lepton Final States in ATLAS Almut M. Pingel1,a, on behalf of the ATLAS Collaboration 1Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen Abstract. The ATLAS detector records collisions from two high-energetic proton beams circulating in the LHC. An integral part of the ATLAS physics program are analyses with tau leptons in the final state. Here an overview is given over the studies done in ATLAS with hadronically-decaying final state tau leptons: Standard Model cross-section measurements of Z ⌧⌧, W ⌧⌫ and tt¯ bbe¯ /µ⌫ ⌧ ⌫; ⌧ polarization measurements ! ! ! had in W ⌧⌫ decays; Higgs searches and various searches for physics beyond the Standard Model. ! 1 Introduction 2 Standard Model cross-section measurements The ATLAS [1] physics program covers a wide range of analyses with tau leptons in the final state, which are The SM processes W ⌧⌫ and Z ⌧⌧ are backgrounds ! ! important both to test the Standard Model (SM) and in in many studies with final state tau leptons, in particular in searches for new physics. In 2010 and 2011, the LHC [2] searches for the Higgs boson. It is therefore important to was operated at a center-of-mass energy of ps = 7 TeV, study and measure the cross-sections precisely. Further- and at ps = 8 TeV in 2012. Physics searches presented more, deviations from predicted SM cross-sections are an 1 here are based on the full 2011 dataset of 4.7 fb− if not indicator for new physics processes. -

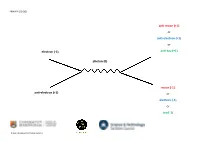

Feynman Diagrams (Pdf)

PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-muon (+1) or anti-electron (+1) or electron (-1) anti-tau (+1) photon (0) muon (-1) anti-electron (+1) or electron (-1) or tau (-1) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-muon (……...) or anti-electron (……..) or electron (…….) anti-tau (……...) ………...…... (…...) muon (…….) anti-electron (……...) or electron (…….) or tau (……..) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-up (-2/3) or anti-down (+1/3) or anti-strange (+1/3) or anti-beauty (+1/3) or anti-top (-2/3) or charm quark (+2/3) anti-charm (-2/3) gluon (0) up (+2/3) or down (-1/3) anti-charm quark (-2/3) or strange (-1/3) or beauty (-1/3) or top (+2/3) or charm (+2/3) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-up (……….) or anti-down (……...) or anti-strange (……...) or anti-beauty (……...) or anti-top (……...) or charm quark (……...) anti-charm (……...) ………...…... (…...) up (……...) or down (……...) or anti-charm quark (……..) strange (……...) or beauty (……...) or top (……...) or charm (……...) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL anti-up (-2/3) or anti-charm (-2/3) muon (-1) W minus (-1) down (-1/3) muon neutrino (0) or strange (-1/3) or beauty (-1/3) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL anti-up (……...) or anti-charm (……...) muon (……...) ………...…... (…...) down (……...) muon neutrino (……...) or strange (……...) or beauty (……...) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni PRIMARY SCHOOL electron neutrino (0) or muon neutrino (0) or tau neutrino (0) tau (-1) Z (0) electron anti-neutrino (0) anti-tau (+1) or muon anti-neutrino (0) or tau anti-neutrino (0) Dr Maria Pavlidou, Prof Cristina Lazzeroni HIGH SCHOOL electron neutrino (……...) or muon neutrino (……...) or tau neutrino (……...) tau (……...) …………. -

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES in PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES IN PHYSICS 1 Elementary Particles in Physics S. Gasiorowicz and P. Langacker Elementary-particle physics deals with the fundamental constituents of mat- ter and their interactions. In the past several decades an enormous amount of experimental information has been accumulated, and many patterns and sys- tematic features have been observed. Highly successful mathematical theories of the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions have been devised and tested. These theories, which are collectively known as the standard model, are almost certainly the correct description of Nature, to first approximation, down to a distance scale 1/1000th the size of the atomic nucleus. There are also spec- ulative but encouraging developments in the attempt to unify these interactions into a simple underlying framework, and even to incorporate quantum gravity in a parameter-free “theory of everything.” In this article we shall attempt to highlight the ways in which information has been organized, and to sketch the outlines of the standard model and its possible extensions. Classification of Particles The particles that have been identified in high-energy experiments fall into dis- tinct classes. There are the leptons (see Electron, Leptons, Neutrino, Muonium), 1 all of which have spin 2 . They may be charged or neutral. The charged lep- tons have electromagnetic as well as weak interactions; the neutral ones only interact weakly. There are three well-defined lepton pairs, the electron (e−) and − the electron neutrino (νe), the muon (µ ) and the muon neutrino (νµ), and the (much heavier) charged lepton, the tau (τ), and its tau neutrino (ντ ). These particles all have antiparticles, in accordance with the predictions of relativistic quantum mechanics (see CPT Theorem). -

Measurement of the Top-Antitop Production Cross Section in the Tau+

EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR NUCLEAR RESEARCH (CERN) CERN-PH-EP/2012-374 2018/11/08 CMS-TOP-11-004 Measurement of the tt production crossp section in the t+jets channel in pp collisions at s = 7 TeV The CMS Collaboration∗ Abstract The top-quark pair production cross section in 7 TeV centre-of-mass energy proton proton collisions is measured using data collected by the CMS detector at the LHC. The measurement uses events with one jet identified as a hadronically-decaying t lepton and at least four additional energetic jets, at least one of which is identified as coming from a b quark. The analysed data sample corresponds to an integrated luminosity of 3.9 fb−1 recorded by a dedicated multijet plus hadronically-decaying t trigger. A neural network has been developed to separate the top-quark pairs from the W+jets and multijet backgrounds. The measured value of stt = 152 ± 12 (stat.) ± 32 (syst.) ± 3 (lum.) pb is consistent with the standard model predictions. Submitted to the European Physical Journal C arXiv:1301.5755v2 [hep-ex] 13 May 2013 c 2018 CERN for the benefit of the CMS Collaboration. CC-BY-3.0 license ∗See Appendix A for the list of collaboration members 1 1 Introduction Top-quark pairs (tt) are copiously produced at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) primarily through gluon-gluon fusion. The measurements of the tt production cross section and branch- ing fractions are important tests of the standard model (SM), since the top quark is expected to play a special role in various extensions of the SM due to its high mass (see for example [1, 2]). -

Measurement Definitions Based on Truth Particles Tancredi Carli Fabio Cossuti

Measurement definitions based on truth particles Tancredi Carli Fabio Cossuti We have contacted representatives of experimental and theoretical “communities” for input to the session. Many thanks to all contributions to the session (see indico agenda). We have linked all contributions on the conference agenda Aim is to introduce the problem, initiate a discussion at the start of the conference We hope that during the conference you think and discuss We have a summary discussion at the last day where your contribution can go in Both sessions are in workshop style, so, please, interact. Motivation ● Measurements at LHC become increasingly precise ● Fast progress on theory side in many areas: ME+PS merging, N(N)LO+PS matching, e.w. corrections etc. full description of final state instead of narrow width approximation e.g. pp -> l l l l vs pp-> Z Z ● Need accurate definitions of measurements to facilitate the comparison of data to theory predictions ● Suitable definition is based on the particle entering the detector ● Use of particle-based definition already standard methodology in HEP ● Standardized tools to compare data and predictions (Hztool, Rivet etc.) 1 Aim ● The following will not necessarily report on what is presently done, but aim to provide “baseline definitions” after discussion in the community as default starting point for refined definitions in dedicated measurements ● There will always be modifications for special analyses ● Proposals are based on informal discussions in and between the experiments (ATLAS and CMS). Work ongoing in the experiments. ALICE has contributed some informal answers where relevant (see contributions to this session) 2 Guiding Principles ● Define observable in theoretical safe and unambiguous way ● Measure observables correcting for detector effects minimizing the dependence on the MC model used ● Measure within detector acceptance (fiducial region) to avoid model dependent large extrapolations ● Define “truth” objects, e.g. -

Discovery of the Tau Lepton

Discovery of the tau lepton Sai Neha Santpur 290E Spring 2020 26 February 2020 <footer> 1 Outline ● World in 1974 ● Motivation to look for third generation leptons ● Discovery of the tau lepton ○ Mark I detector at SPEAR e+e- collider ○ Physics analysis ● Confirmation of tau discovery ● Tau research today Feb 26, 2020 S.<footer> N. Santpur 2 2 World in 1974 ● Feb 26, 2020 S.<footer> N. Santpur 3 3 Motivation for third generation of leptons ● Two leptons then: ○ Electron: m=0.5MeV, discovered in 1897 ○ Muon: m=105MeV, discovered in 1937 ● 1968-1974 time period ● The e-μ problem: ○ How does the muon differ from electrons? ○ Studies compared e-p vs. μ-p inelastic differential crosssections but did not show any anamolies. i.e. the muon interaction with hadrons was exactly similar to electron ○ Same is true for elastic scattering of e-p vs. μ-p ○ These results were not helpful in figuring out the differences between electron and muon ● Proposition(?): ○ May be there is another charged lepton out there that will explain what is different between electron, muon and this new lepton Feb 26, 2020 S.<footer> N. Santpur 4 4 Varieties of leptons considered ● Sequential leptons (tau like lepton) ● Excited leptons ● Paraleptons ● Ortholeptons ● Long-lived particles ● Stable leptons Feb 26, 2020 S.<footer> N. Santpur 5 5 How to search for sequential leptons? ● Searches in particle beams ● Production of new leptons by e+e- annihilation ● Photoproduction of new leptons ● Production of new leptons in p - p collisions ● Searches in lepton bremsstrahlung ● Searches in charged lepton-proton inelastic scattering ● Searches in neutrino-nucleon inelastic scattering - l Something like + l Feb 26, 2020 S.<footer> N. -

Particle Physics

Particle Physics 12.3.1 Outline the concept of antiparticles and give examples 12.3.2 Outline the concepts of particle production and annihilation and apply the conservation laws to these processes. Every known particle has an associated anti-particle. That is a particle that has all the opposite quantum numbers, electric charge, lepton or baryon number, strangeness etc. As far as we know anti-matter does not have negative mass and still falls down. Tests have been done to see if anti-matter “falls up.” No conclusion test has been done to show that anti-matter falls up. When a particle and its associated antiparticle collide they completely and totally annihilate turning into pure energy, in accordance to Einstein’s relation of E = mc2. An example of this is the annihilation of an electron and a positron (positively charged electron, basically). When they collide their mass is turned into energy in the form of two high energy gamma rays. During the annihilation mass-energy and momentum are conserved. If a photon has a higher energy than the rest mass of the electron and positron, it is possible for a electron and positron to be spontaneously created. 12.3.4 List the three classes of fundamental particle 12.3.5 State that there are three classes of observed particle There are over 240 subatomic particles. We classify them by how they interact with forces. There are 3 classes of observed particles. Class of Description Example Particle Fundamental particles. Not effected by the strong Electron, Muon, Tau, force. There are 3 particles and associated Electron Neutrino, Lepton neutrinos. -

What Is a Muon?

What is a Muon? A muon is a type of subatomic particle. The name is pronounced “myoo-on,” and comes from the Greek letter µ, which we spell “mu” and pronounce “myoo.” A muon is a type of particle very much like an electron. In fact, it is exactly the same as an electron – except heavier. The mass of a muon is 207 times the mass of an electron. You can remember or look up (or take our word for it) that the mass of a proton, by contrast, is about 1,800 times the mass of an electron. So a muon has all the properties of an electron, but is more similar in mass to the big clunkiness (in relative terms) of a proton or other nuclear particle. A muon, however, is not made up of any other particles. It is not a bag of electrons or of anything else, but appears to be its own elementary or fundamental particle. It’s just a heavier version of an ordinary electron. If the existence of the muon seems strange and unnecessary to you, you are in good company. The world-famous physicist I. I. Rabi, when first told of the discovery of the muon, said in response, “Who ordered that?” There’s a good reason why the muon is such an unfamiliar particle: muons are radioactive, and they decay with a half-life of 1.52 microseconds. That’s 1.52 x 10-6 seconds, or 1.52 millionths of a second. Not 5,700 years, like 14C, but 1.52 millionths of a second! Muons don’t stick around long enough for anything ordinary to be made out of them.