The Blue Koran Revisited*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Musée Aga Khan Célèbre La Créativité Et Les Contributions Artistiques Des Immigrants Au Cours D’Une Saison Qui Fait La Part Belle À L’Immigration

Le Musée Aga Khan célèbre la créativité et les contributions artistiques des immigrants au cours d’une saison qui fait la part belle à l’immigration Cinquante-et-un artistes plasticiens, 15 spectacles et 10 orateurs représentant plus de 50 pays seront à l’honneur lors de cette saison dédiée à l’immigration. Toronto, Canada, le 4 mars 2020 - Loin des gros-titres sur l’augmentation de la migration dans le monde, le Musée Aga Khan célèbrera les contributions artistiques des immigrants et des réfugiés à l’occasion de sa nouvelle saison. Cette saison dédiée à l’immigration proposera trois expositions mettant en lumière la créativité des migrants et les contributions artistiques qu’ils apportent tout autour du monde. Aux côtés d’artistes et de leaders d’opinion venant du monde entier, ces expositions d’avant-garde présenteront des individus remarquables qui utilisent l’art et la culture pour surmonter l’adversité, construire leurs vies et enrichir leurs communautés malgré les déplacements de masse, le changement climatique et les bouleversements économiques. « À l’heure où la migration dans le monde est plus importante que jamais, nous, au Musée Aga Khan, pensons qu’il est de notre devoir de réfuter ces rumeurs qui dépeignent les immigrants et les réfugiés comme une menace pour l’intégrité de nos communautés », a déclaré Henry S. Kim, administrateur du Musée Aga Khan. « En tant que Canadiens, nous bénéficions énormément de l’arrivée d’immigrants et des nouveaux regards qu’ils apportent. En saisissant les occasions qui se présentent à eux au mépris de l’adversité, ils incarnent ce qu’il y a de mieux dans l’esprit humain. -

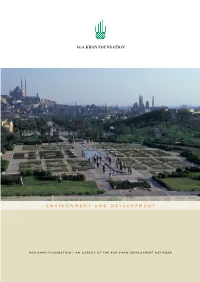

Environment and Development AGA KHAN FOUNDATION

AGA KHAN FOUNDATION E N V I R ON ME NT A ND D EVEL O PME NT AG A K H A N F O U N D AT I O N – A N A G E N C Y O F TH E A G A K H A N D EVEL O PME NT N E T W O RK 1 COver: AL-AZHar Park, CAIRO, EGypT THE CREATION OF A PARK FOR THE CITIZENS OF THE EGYPTIAN CAPITAL, ON A 30-HECTARE (74-ACRE) MOUND OF RUBBLE ADJACENT TO THE HISTORIC CITY, HAS EVOLVED WELL BEYOND THE GREEN SPACE OF THE PARK TO INCLUDE A VARIETY OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC INITIATIVES IN THE NEIGHBOURING DARB AL-AHMAR DISTRICT. THE PARK ITSELF ATTRACTS AN AVERAGE OF 3,000 PEOPLE A DAY AND AS MANY AS 10,000 DAILY DURING RAMADAN. 2 CONTENTS 2 Foreword 3 About the Aga Khan Foundation 5 The Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Fund for the Environment Case Studies: 9 • A “Green Lung” for Cairo 10 • Environmental Water and Sanitation 11 • Reforestation and Land Reclamation 12 • Environmentally Friendly Tourism Infrastructure 14 • Water Conservation 16 • Sustainable Energy for Developing Economies 18 • Fuel-Saving Stoves and Healthier Houses 19 • A University for Development in Mountain Environments 20 Environmental Awards for AKDN Programmes 24 About Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan and His Highness the Aga Khan 24 About the Aga Khan Development Network 26 AKDN Partners in Environment and Development 1 FOREWORD RiGHT: QESHLAQ-I-BAIKH VILLAGE, AFGHANISTAN IN recent Years, A DROught has COmpOunded difficulties EXperienced due TO the large-scale destructiON OF the agricultural infrastruc- ture and the sudden influX OF Afghan returnees frOM ABROad. -

United Nations Archives

- \ • <\ � Cj \Cl OL � I \.L �- � � l Date arrived date departed Purp:>se I Freetown 5 June 6 June Official visit witH Mrs. Perez de CUellar. Weds. 5 une: ar i ed by private plane frcm Al::uja, Ni ria. t at airp:>rt by Vice- depart by helicopter for guest President lial � c;;;Qerif and.FM �1 /** house. Kar .i.m Korcma. 1 �Hdga �g8gpfiORSffi9iOR&r of SG by Vice es. Cherif (with Mrs. Perez de CUellar) , fo �owed by dinner by Mr. Onder Yucer (UNDP -Res. Coordinator) in honour of SG and Mrs. Pere-z de CUellar, and attended by reps. of UN System and Specialized - • 6 Formal welco,ing ceranony at State House, Agencies Thurs. June : * *� with Pres • folloY.ed by rreeting with: Jos� � f:iaroh (S� � .. .. s t� �); encies ; f ; Wn� � HADPRESS ENCOUNTER; � �· L� Conakry, Guinea. Conakry 6 June 1991 8 June 1991 Official visit with Mrs. Perez de CUellar. Thurs. 6 June: arrived frcm Freetown by private plane. Met at ai rt by . President Conte (GUJNEA) , ilas�®i1�d ** andmet �iefly with of Honour. *!NStaxiak�n . press. met/w1 ��es. Conte; and FM �. Private d· er. Fri. 7 June ..... _ ...... Had rreeting with H.E, • Sylla (Min. for LiEut. "·-.p..J_�ing and Cooperll'tion) and H. E. Mx¥. 6fiji� Col. traore (Fr.'i)-1- met with reps. of UN Specialzied agenci es; priv:�te luncheon;. Boat trip to !les de Loos (wi��s. Perez de CUellar); Briefing by �-�ekio (�R· �-n.,ur;mP) on Technical. �ting �t...._ UN and/tfffli8f"als.� Attended 5)tld made toast""-at- banquet in his honour bf FM 'Fraore (with Mrs. -

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

s t a t u t e of the office of the united nations high commissioner Published by: for refugees UNHCR Communications and Public Information Service P.O. Box 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland www.unhcr.org For information and inquiries, please contact: Communications and Public Information Service [email protected] General Assembly Resolution 428 (V) of 14 December 1950 statute of the office of the united nations high commissioner for refugees with an Introductory Note by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees s t a t u t e o f t h e o f f i c e o f t h e u n h c r 1 introductory note by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) In ResolutIon 319 (IV) , of 3 December 1949, the United Nations General Assembly decided to establish a High Commissioner’s Office for Refugees as of 1 January 1951. The Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees was adopted by the General Assembly on 14 December 1950 as Annex to Resolution 428 (V).n I this Resolution, reproduced on page 4, the Assembly also called upon the Governments to cooperate with the High Com- missioner in the performance of his or her functions concerning refugees fall- ing under the competence of the Office. In accordance with the Statute, the work of the High Commissioner is humanitarian and social and of an entirely non-political character. The functions of the High Commissioner are defined in the Statute and in various Resolutions subsequently adopted by the General Assembly. -

Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre As Alternative Planning Model for Mosque Development

Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre as alternative planning model for mosque development. Haris S. Khan A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. April 12, 2021 ABSTRACT Multiculturalism is widely celebrated in Toronto as a cornerstone of our society. When multiculturalism moves outside festivals and food, groups make spatial claims of citizenship and identity, the experience is somewhat different. There is no doubt that some racialized minorities have fared well in the Greater Toronto Area. Their growth is no longer confined to low-income enclaves within the City of Toronto but into city suburbs. This growth comes with the increased demand for spatial citizenship through culturally suited social, recreational, commercial and religious space. It is here where the experience of multiculturalism changes. The inherently political and contentious process of land use planning and its response to individual groups needs for certain type of developments is the broad focus of this paper. The paper looks at how the practice of planning in the Greater Toronto Area has responded to social diversity in cities by studying the specific process of mosque development for Muslim Canadians. Mosque development has faced challenges in the planning arena through staunch opposition that often hides behind legitimate planning technicalities to express the personal distaste for a group of people. My goal was to understand the role of planning departments in recognizing and responding to the rise of these conflicts in land use development. -

Glaze Production at an Early Islamic Workshop in Al-Andalus

Glaze production at an Early Islamic workshop in al-Andalus Elena Salinas1, Trinitat Pradell1 Judit Molera 2 1Physics Department and Barcelona Research Centre in Multiscale Science and Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Campus Diagonal Besòs, Av. Eduard Maristany, 10-14 08019 Barcelona, Spain 2GR-MECAMAT, Universitat de Vic-Universitat Central de Catalunya (UVIC-UCC), Campus Torre dels Frares, C/ de la Laura 13, 08500, Vic, Spain Abstract The study and analysis of the materials found in one of the earliest Islamic glazed ceramics workshop in al-Andalus (Pechina) dating from the second half of the 9th century, including fritting vessels, kiln furniture, wasters and slags, and a glass chunk, has revealed the materials used and methods of production. Galena was oxidised to obtain PbO in the workshop. Fritting of the glaze involved a two-stage process for which two different types of vessels were used. The fritting process ended with a melt which was poured to obtain a high lead glass. The ground glass was applied over the biscuit fired ceramics, and fired to a temperature high enough to soften the glaze and adhere it onto the ceramic surface. Evidences of a similar process was found in a later workshop in San Nicolas (10th century) which demonstrates the persistence of the technique in al-Andalus during the caliphal period. There is little evidence of early Islamic glaze manufacture at kiln sites and in contrast to the glass workshops the glazed ceramics workshops have not been studied. Consequently, this study adds valuable information to the currently very limited knowledge about the early glaze technology in Dar al-Islam. -

Timeline / 400 to 1550 / TUNISIA

Timeline / 400 to 1550 / TUNISIA Date Country | Description 533 A.D. Tunisia Byzantine reconquest of Africa led by the Byzantine general Belisarius. End of the Vandal kingdom. 534 - 548 A.D. Tunisia Berber insurrections threaten the Byzantine army, which suffered repeated setbacks. 582 - 602 A.D. Tunisia Reorganisation of the Byzantine Empire and institution of the Exarchate of Carthage, consolidating the pre-eminence of the military. 647 A.D. Tunisia First expedition of Muslim Arabs in Ifriqiya. Victory at Sufetula (Sbeitla). 665 A.D. Tunisia Second Arab expedition. Victory at Hadrumetum (Sousse). 670 A.D. Tunisia Third Arab expedition led by ‘Uqba (Okba) ibn Nafi, who founds the town of Kairouan. 698 A.D. Tunisia Carthage conquered by the Arabs under the leadership of Hassan ibn Numan. 705 A.D. Tunisia Musa ibn Nossayr becomes the first governor of Ifriqiya. 711 A.D. Tunisia The Muslims begin the conquest of Spain under the leadership of Tarik ibn Ziyad. 739 - 742 A.D. Tunisia Berber insurrections shake the country. Arab pacification puts an end to the insecurity and prompts economic growth. 827 A.D. Tunisia The Aghlabids begin the conquest of Sicily. Date Country | Description 836 A.D. Tunisia Construction of the Great Mosque of Kairouan. 863 A.D. Tunisia Construction of the Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis. 876 A.D. Tunisia Foundation of the town of Raqqada a few kilometres outside Kairouan. 921 A.D. Tunisia Foundation of the town of Mahdia, capital of the Fatimids. 947 A.D. Tunisia Foundation of princely town of Sabra-al Mansuriya. 971 - 973 A.D. -

Holy Coverings in the Tareq Rajab Museum the Origin of the Tradition of Covering the Ka'aba with Cloth Is Lost In

About the journal Contents 02 18 April 2011 The Journey to the Centre Aly Gabr 09 9 May 2011 China and the Islamic World: The evidence of 12th and 13th century Northern Syria Martine Muller-Weiner 22 26 September 2011 Holy Coverings in the Tareq Rajab Museum Ziad T Alsayed Rajab 27 17 October 2011 A Brief History of the Ismaili D’awa Adel Salem al-Abdul Jader 31 28 November 2011 The Kingdom of Saba: Current Research by the German Archaeological Institute in South Arabia (Yemen) Iris Gerlach 38 5 December 2011 The Oriental Pearl in the Maritime Trade Annie Montigny 43 13 December 2011 Raili and Reima Pietilä Jarno Paltonen 49 9 January 2012 Islamic Heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina Kenan Musić This publication is sponsored in part by: LNS 1785 J Fabricated from gold, worked in kundan technique and set with rubies and emeralds Height 9 mm; diameter 100 mm India, Mughal, c. 1st quarter 17th century AD Hadeeth ad-Dar 1 Volume 37 The Journey to the Centre be performed in congregation in a mosque although as opposed to a physical one, meaning that he the whole earth that we know is a potential place for employed his intuition with what he dealt with. the performance of that daily activity. This notion He saw himself as a tripartite being composed of makes the earth a potential vast mosque. body (jism), soul (nafs), and spirit (rouh). Without the union of these three parts he believed he/ I am sure that the question arises in some of she would be demeaned in his/her existence and your minds: does God really expects us to show unbalanced. -

The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: an Introduction

Please provide footnote text Chapter 1 The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: An Introduction Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick, and Mariam Rosser-Owen This book takes an interdisciplinary and transregional approach to the Aghlabid dynasty and ninth-century North Africa, to highlight the region’s im- portant interchange with other medieval societies in the Mediterranean and beyond. It comprises new invited essays alongside revised versions of select papers presented at the symposium, “The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa,” held in London in May 2014 under the aegis of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.1 This event was originally intended as a small interdisciplinary workshop on the his- tory and material culture of the Aghlabid dynasty of Ifriqiya and its immediate neighbors in the region, but it rapidly became a larger event when we real- ized the scale of scholarly interest in the topic. The workshop brought scholars together from different national as well as disciplinary traditions to consider the Aghlabids and their neighbors, with the aim of moving toward a more in- tegrated understanding of this crucial dynasty and period within the Islamic world. Our stated aim in the call for papers was to consider North Africa not as a peripheral frontier whose artistic production was inferior to or derivative of trends in the Abbasid heartlands of Iraq and Egypt, which is how it has long been situated in the history of Islamic art, but as one of the vibrant centers of the early medieval dār al-Islām. In doing so, we hoped not only to reevaluate problematic yet persistent notions of the region’s peripherality in Islamic (art) history and archaeology, but also to illuminate processes of acculturation and interaction between ninth-century North Africa, Iberia, Sicily/Italy, and other regions. -

Coloured Dots and the Question of Regional Origins in Early Qur'ans: Part II', Journal of Qur’Anic Studies, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Coloured dots and the question of regional origins in early Qur'ans Citation for published version: George, A 2015, 'Coloured dots and the question of regional origins in early Qur'ans: Part II', Journal of Qur’anic Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 75-102. https://doi.org/10.3366/jqs.2015.0196 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/jqs.2015.0196 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Qur’anic Studies General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Coloured dots and the question of regional origins in early Qurʾans: Part II Part I of the present article (Journal of Qurʾanic Studies, 17:1) began with a summary of remarks about regional patterns of vocalisation offered by the Andalusī scholar of the Qurʾan al-Dānī (371-444/982-1053), primarily in al-Muḥkam fī naqṭ al-maṣāḥif. These assertions were then confronted with extant manuscripts of the third to fourth/ninth to tenth centuries that can be ascribed to the broad region between Syria, Iraq and Iran. -

KT 3-4-2014 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, APRIL 3, 2014 JAMADA ALTHANI 3, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait, Chileans Qatar emir Real overwhelm NATO to return homes visits Sudan Dortmund as strengthen after huge at time of Ronaldo equals cooperation5 quake kills7 6 Gulf15 tensions scoring20 record Commercial Bank votes to Max 22º become sharia-compliant Min 16º High Tide 02:27 & 13:46 Most shareholders approve conversion to Islamic banking Low Tide 08:16 & 20:53 40 PAGES NO: 16124 150 FILS KUWAIT: Commercial Bank of Kuwait (also known Basel III,” Mousa disclosed. conspiracy theories as Al-Tijari) announced yesterday it will convert On the financial results of 2013, Mousa affirmed from a conventional bank to a sharia-compliant the bank’s commitment to the principles of corpo- one. The decision was approved by a majority of 85 rate governance in all its policies and activities that It’s not a percent of the shareholders who attended ordi- are subject to constant revision. “The shareholders’ nary and extraordinary meetings of the general equity in the bank grew by 1.8 percent to KD 562 one-man show assembly, Board Chairman Ali Mousa Al-Mousa million compared to the previous year, the third announced. largest in Kuwait. The total value of assets grew by “Although the majority of the shareholders vot- 7.1 percent year on year to KD 3.9 billion, the fifth ed for the move which was on the top of the agen- largest in the country’s banking sector,” Mousa said. da of the ordinary meeting, the decision does not The bank’s operating and net profits hit KD 102 take effect immediately - it is just a first step in a million and KD 23.5 million respectively in 2013, By Badrya Darwish legal process involving several studies and he added.