Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre As Alternative Planning Model for Mosque Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Musée Aga Khan Célèbre La Créativité Et Les Contributions Artistiques Des Immigrants Au Cours D’Une Saison Qui Fait La Part Belle À L’Immigration

Le Musée Aga Khan célèbre la créativité et les contributions artistiques des immigrants au cours d’une saison qui fait la part belle à l’immigration Cinquante-et-un artistes plasticiens, 15 spectacles et 10 orateurs représentant plus de 50 pays seront à l’honneur lors de cette saison dédiée à l’immigration. Toronto, Canada, le 4 mars 2020 - Loin des gros-titres sur l’augmentation de la migration dans le monde, le Musée Aga Khan célèbrera les contributions artistiques des immigrants et des réfugiés à l’occasion de sa nouvelle saison. Cette saison dédiée à l’immigration proposera trois expositions mettant en lumière la créativité des migrants et les contributions artistiques qu’ils apportent tout autour du monde. Aux côtés d’artistes et de leaders d’opinion venant du monde entier, ces expositions d’avant-garde présenteront des individus remarquables qui utilisent l’art et la culture pour surmonter l’adversité, construire leurs vies et enrichir leurs communautés malgré les déplacements de masse, le changement climatique et les bouleversements économiques. « À l’heure où la migration dans le monde est plus importante que jamais, nous, au Musée Aga Khan, pensons qu’il est de notre devoir de réfuter ces rumeurs qui dépeignent les immigrants et les réfugiés comme une menace pour l’intégrité de nos communautés », a déclaré Henry S. Kim, administrateur du Musée Aga Khan. « En tant que Canadiens, nous bénéficions énormément de l’arrivée d’immigrants et des nouveaux regards qu’ils apportent. En saisissant les occasions qui se présentent à eux au mépris de l’adversité, ils incarnent ce qu’il y a de mieux dans l’esprit humain. -

Newsletter Sample4

Notes & News Notes & News www.vivanext.com April 2012 Edition News New Viva Bus Depot in Markham The City of Vaughan’s downtown core will undergo a transformation over the next several years. Encompass- ing 125-acres, development plans include oce and residential towers, shopping and entertainment complexes, plenty of green spaces and pedestrian walkways, and, of course, vivaNext rapid transit connec- tions. In recognition of all the exciting changes to come, Vaughan City Council determined that a change of name – from Vaughan Corporate Centre – was in order to better reect the true vision and future of this key hub. This summer, the City held a contest where people were encouraged to submit their suggestions. Almost 1,600 entries were received, including Central Vaughan, Vaughan Gateway, Vaughan Mosaic Centre and Vaughan Nexus. In the end, Vaughan Metropolitan Centre was chosen as the winning entry by the City subcommittee. Davis Drive Rapidway Construction - Ready, Set, GO! Last year we accomplished a lot on Davis Drive, and as of this spring we’ll be moving full speed ahead on construc- tion to build the rapidway. Starting soon, you’ll see a lot of utility companies along the corridor working to relocate gas, power, telecommunications, etc. Later this summer, we’ll be working on the Keith Bridge near the Tannery and doing some work near Southlake hospital. Watch for updates about all of this work, with more details to come. The Davis Drive rapidway will be complete in 2015, and we’re bringing an exceptional rapid transit system that will connect to other parts of York Region and help shape Newmarket’s growth. -

The Vaughan Mills Centre Secondary Plan

Clause No. 13 in Report No. 11 of Committee of the Whole was adopted, as amended, by the Council of The Regional Municipality of York at its meeting held on June 26, 2014. 13 AMENDMENT NO. 2 TO THE VAUGHAN OFFICIAL PLAN (2010) – THE VAUGHAN MILLS CENTRE SECONDARY PLAN Committee of the Whole recommends: 1. Receipt of the deputation by Mark Flowers, Davies Howe Partners LLP, on behalf of a number of landowners who own lands between Weston Road and Highway 400, in the City of Vaughan. 2. Receipt of the following communications: 1. Jeffrey A. Abrams, City Clerk, City of Vaughan, dated March 24, 2014. 2. Michael Bissett, Bousfields Inc., on behalf of Rutherford Land Development Corporation, dated June 9, 2014. 3. A. Milliken Heisey, Papazian Heisey Myers, on behalf of Canadian National Railway, dated June 10, 2014. 4. Nima Kia, Lakeshore Group, on behalf of Stronach Trust, dated June 11, 2014 5. Steven Zakem, Aird & Berlis LLP, on behalf of Granite Real Estate Investment Trust and Magna International Inc., dated June 11, 2014 6. Mark Flowers, Davies Howe Partners LLP, on behalf of H & L Tile Inc. and Ledbury Investments Ltd., dated June 11, 2014 7. Meaghan McDermid, Davies Howe Partners LLP, on behalf of Tesmar Holdings Inc., dated June 11, 2014. Clause No. 13, Report No. 11 2 Committee of the Whole June 12, 2014 3. Adoption of the following recommendations in the report dated May 29, 2014 from the Commissioner of Transportation and Community Planning, with the following amendment to Recommendation 2: 2. Council protect for the potential re-establishment of a minor collector road connection to Weston Road opposite Astona Boulevard, to be reviewed by staff no sooner than 2019. -

7080 Yonge Street in the City of Vaughan – Official Plan and Zoning By-Law Amendment Applications – Request for Direction Report

REPORT FOR ACTION 7080 Yonge Street in the City of Vaughan – Official Plan and Zoning By-law Amendment Applications – Request for Direction Report Date: February 5, 2021 To: Planning and Housing Committee From: Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning Wards: All SUMMARY This report responds to applications filed in the City of Vaughan to amend the City of Vaughan Official Plan and the City of Vaughan Zoning By-law which have been circulated to the City of Toronto in accordance with the requirements of the Planning Act given the proximity to the City of Toronto. The report identifies the concerns of City Planning staff and makes recommendations on future steps to protect the City's interests concerning the applications. The applications are on the west side of Yonge Street, north of Steeles Avenue West. The applications propose two mixed-use buildings with a total of 652 residential units. The towers would be forty and twenty storeys in height and overall the proposal has a Floor Space Index ("FSI") of 9.84. The Deputy City Manager, Infrastructure Development for the City of Vaughan has written a report to the City of Vaughan's Committee of the Whole regarding each application outlining some preliminary concerns with the applications including the proposed heights and densities. RECOMMENDATIONS The Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning, recommends that: 1. City Council endorse the January 18, 2021 letter from the Director, Community Planning, North York District (Attachment 3) to the City of Vaughan's Committee of the Whole which identify the concerns with the application at 7080 Yonge Street, including height and density. -

Final Report RECOMMENDED WARD ALIGNMENT

Final Report RECOMMENDED WARD ALIGNMENT DECEMBER 2016 VAUGHAN WARD BOUNDARY REVIEW FINAL REPORT RECOMMENDED WARD ALIGNMENT DECEMBER 2016 CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 7 3. WHY A VAUGHAN WARD BOUNDARY REVIEW (VAUGHAN WBR)? ......... 9 3.1 Purpose of the Vaughan WBR.................................................................................... 9 3.2 What is Effective Representation ............................................................................... 9 3.3 Examining the Status Quo ........................................................................................ 12 3.4 The Role of the OMB ............................................................................................... 13 4. VAUGHAN WBR STEP-BY-STEP .......................................................................... 14 5. VAUGHAN WBR COMMUNICATION & OUTREACH ..................................... 15 6. DEVELOPING THE OPTIONS ............................................................................... 17 7. THE PREFERRED OPTION .................................................................................... 22 7.1 Round 1 Civic Engagement and Public Consultation .............................................. 22 7.2 The Preferred Option and Refinements .................................................................... 22 7.3 Refinements -

Interim Dividend

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form IEPF‐2 CIN/BCIN L34101PN1961PLC015735 Prefill Company/Bank GABRIEL INDIA LIMITED Date of AGM 13‐AUG‐2019 FY‐1 FY‐2 FY‐3 FY‐4 FY‐5 FY‐6 FY‐7 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 984364.70 Number of underlying Shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of matured deposits 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposits 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of Other Investment Types 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Validate Clear Is the shares Is the transfer from Proposed Date of Investment Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id‐Client Id‐ Amount Joint Holder unpaid Investor First Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF PAN Date of Birth Aadhar Number Nominee Name Remarks (amount / Financial Year Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred Name suspense (DD‐MON‐YYYY) shares )under account any litigation. -

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

![Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5083/diamond-jubilee-his-highness-the-aga-khan-iv-1957-2017-145083.webp)

Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]

DIAMOND JUBILEE HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN IV [1957 – 2017] . The Diamond Jubilee What is the Diamond Jubilee? The Diamond Jubilee marks the 60th anniversary of His Highness the Aga Khan’s leadership as the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslim Community. On 11th July, 1957, the Aga Khan, at the age of 20, assumed the hereditary office of Imam established by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family), following the passing of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. Why is the Community celebrating His Highness the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee? The commemoration of the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee is in keeping with the Ismaili Community’s longstanding tradition of marking historic milestones. Over the past six decades, the Aga Khan has transformed the quality of life of hundreds of millions of people around the world. In the areas of health, education, cultural revitalisation, and economic empowerment, he has inspired excellence and worked to improve living conditions and opportunities in some of the world’s most remote and troubled regions. The Diamond Jubilee is an opportunity for the Shia Ismaili Muslim community, partners of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), and government and faith community leaders in over 25 countries to express their appreciation for His Highness’s leadership and commitment to improve the quality of life of the world’s most vulnerable populations. It is also an occasion for His Highness to recognise the friendship and longstanding support of leaders of governments and partners in the work of the Imamat and to set the direction for the future. -

Longines Turf Winner Notes- Owner, Aga Khan

H.H. Aga Khan Born: Dec. 13, 1936, Geneva, Switzerland Family: Children, Rahim Aga Khan, Zahra Aga Khan, Aly Muhammad Aga Khan, Hussain Aga Khan Breeders’ Cup Record: 15-2-0-2 | $3,447,400 • Billionaire, philanthropist and spiritual leader, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV is also well known as an owner and breeder of Thoroughbreds. • Has two previous Breeders’ Cup winners – Lashkari (GB), captured the inaugural running of Turf (G1) in 1984 and Kalanisi (IRE) won 2000 edition of race. • This year, is targeting the $4 million Longines Turf with his good European filly Tarnawa (IRE), who was also cross-entered for the $2 million Maker’s Mark Filly & Mare Turf (G1) after earning an automatic entry via the Breeders’ Cup Challenge “Win & You’re In” series upon winning Longines Prix de l’Opera (G1) Oct. 4 at Longchamp. Perfect in three 2020 starts, the homebred also won Prix Vermeille (G1) in September. • Powerhouse on the international racing stage. Has won the Epsom Derby five times, including the record 10-length victory in 1981 by the ill-fated Shergar (GB), who was famously kidnapped and never found. In 2000, Sinndar (IRE) became the first horse to win Epsom Derby, Irish Derby (G1) and Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe (G1) the same season. In 2008, his brilliant unbeaten filly Zarkava (IRE) won the Arc and was named Europe’s Cartier Horse of the Year. • Trainers include Ireland-based Dermot Weld, Michael Halford and beginning in 2021 former Irish champion jockey Johnny Murtagh, who rode Kalanisi to his Breeders’ Cup win, and France-based Alain de Royer-Dupre, Jean-Claude Rouget, Mikel Delzangles and Francis-Henri Graffard • Almost exclusively races homebreds but is ever keen to acquire new bloodlines, evidenced by acquisition of the late Francois Dupre's stock in 1977, the late Marcel Boussac’s in 1978 and Jean-Luc Lagardere’s in 2005. -

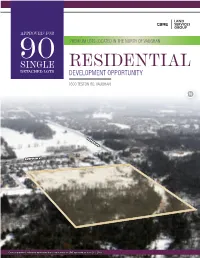

Premium Lots Located in the North of Vaughan

PREMIUM LOTS LOCATED IN THE NORTH OF VAUGHAN 1600 TESTON RD, VAUGHAN TESTON RD DUFFERIN ST 1 Council approved settlement agreement that is expected to be LPAT approved on June 26th, 2019. DEVELOPMENT STATUS DEVELOPMENT BREAKDOWN In July 2018, the Mackenzie Ridge Ratepayers Group appealed Type Unit Area (ac.) City Council’s decision on the Official Plan Amendment (OPA), Favourable Demographics in 40 ft. Single Detached 79 8.55 Zoning By-Law Amendment (ZBLA) and Draft Plan application for a High Demand Area the Property to the LPAT. The concerns of the ratepayers group 59 ft. Single Detached 3 0.42 was addressed through an added 10 metre wide, open space 1600 TESTON RD, VAUGHAN At $127,000, the average income 65 ft. Single Detached 8 1.21 landscape buffer adjacent to the existing homes on Giorgia within 3 km of the Site is $15,000 Crescent and Germana Place. On March 4th, 2019, a settlement Natural Heritage 13.91 higher than the average income of agreement was approved between Vaughan City Council and the The Land Services Group is pleased to offer for sale the property located at 1600 $112,000 in the City of Vaughan. owner. A Case Management Meeting is scheduled for June 26th, Vegetation Protection Zone 1.6 Teston Road (the “Property” or “Site”) in the City of Vaughan. The Site has a Council 2019, where the LPAT is expected to sign off on the settlement Stormwater Management Block 2.57 approved settlement agreement for 90 single detached lots, following an appeal to the agreement. A revised draft plan has been created to ensure a Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) by the Mackenzie Ridge Ratepayers Group over buffer between the existing residential lots and the development. -

Amendment No. 744 to the Vaughan Official Plan – the Block 40/47 Secondary Plan

Clause No. 7 in Report No. 13 of Committee of the Whole was adopted, without amendment, by the Council of The Regional Municipality of York at its meeting held on September 11, 2014. Council also received the following communications: 1. Gillian Evans and David Toyne, Landowners, City of Vaughan, dated September 10, 2014. 2. Quinto Annibale, Partner, Loopstra Nixon LLP, on behalf of Maria Pandolfo, Yolanda Pandolfo, Laura Pandolfo, Giuseppe Pandolfo and Cathy Campione, dated September 10, 2014. 7 AMENDMENT NO. 744 TO THE VAUGHAN OFFICIAL PLAN – THE BLOCK 40/47 SECONDARY PLAN Committee of the Whole recommends: 1. Receipt of the following communications: 1. David Donnelly, Barrister & Solicitor, Donnelly Law, on behalf of Ms. Gillian Evans and Mr. David Toyne, dated August 7, 2014. 2. Quinto Annibale, Partner, Loopstra Nixon LLP, on behalf of Maria Pandolfo, Yolanda Pandolfo, Laura Pandolfo, Giuseppe Pandolfo and Cathy Campione, dated September 3, 2014. 2. Receipt of the following deputations: 1. Quinto Annibale, Partner, Loopstra Nixon LLP, on behalf of Maria Pandolfo, Yolanda Pandolfo, Laura Pandolfo, Giuseppe Pandolfo and Cathy Campione regarding 10390 Pine Valley Drive, City of Vaughan. 2. Mark Yarranton, Partner, KLM Planning Partners Inc. on behalf of Block 40/47 Developers Group regarding the Block 40/47 lands. 3. Gillian Evans, Landowner, City of Vaughan, regarding 10240 Pine Valley Drive, City of Vaughan. Clause No. 7, Report No. 13 2 Committee of the Whole September 4, 2014 3. Receipt of the private verbal update from the Regional Solicitor. 4. Adoption of the following recommendations contained in the report dated August 13, 2014 from the Commissioner of Transportation and Community Planning: 1. -

Aga Khan Museum Set to Reopen After Three-Month Closure with New Safety Measures and Reinvented Programming

PRESS RELEASE Aga Khan Museum Set to Reopen after Three-Month Closure with New Safety Measures and Reinvented Programming The Museum’s Rebuild 2020 program features three exhibitions highlighting human stories of strength and resilience Toronto — Monday, June 22, 2020 — The Aga Khan Museum is set to reopen its door with a slew of new programming and safety measures encouraging visitors to reconnect with art and culture in an inspiring, physical-distancing-friendly environment. Following a provincial directive allowing the reopening of museums and galleries in Toronto, the Museum, including all galleries, the Shop, and the Diwan restaurant, will open its doors on Saturday, June 27, 2020. A host of new safety measures is already in place. All visitors, staff, and volunteers will be expected to follow new guidelines designed to protect everyone who steps inside the building. The flow of visitors will be controlled through the use of timed-entry ticketing, and new signage will help prevent clustering and remind visitors to maintain proper distance. The Museum has implemented enhanced cleaning protocols, installed touch-free automatic doors, and added new hand-sanitizing stations to limit the spread of germs. “The safety of our visitors and staff is our primary focus,” said Henry Kim, the Museum’s Director and CEO. “Our intention is to make their return to the Museum a safe and enjoyable experience. For this reason, we have instituted a number of measures that don’t just comply with public health directives, but exceed them to ensure the highest standards for keeping people safe.” In addition, the Museum has announced its redeveloped slate of programming for the year.