The Theatre of Affect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage Violence, Power and the Director an Examination

STAGE VIOLENCE, POWER AND THE DIRECTOR AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE by Jordan Matthew Walsh Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh May 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jordan Matthew Walsh It was defended on April 13th, 2012 and approved by Jesse Berger, Artistic Director, Red Bull Theater Company Cynthia Croot, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Annmarie Duggan, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department 2 Copyright © by Jordan Matthew Walsh 2012 3 STAGE VIOLENCE AND POWER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE Jordan Matthew Walsh, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This exploration of stage violence is aimed at grappling with the moral, theoretical and practical difficulties of staging acts of extreme violence on stage and, consequently, with the impact that these representations have on actors and audience. My hypothesis is as follows: an act of violence enacted on stage and viewed by an audience can act as a catalyst for the coming together of that audience in defense of humanity, a togetherness in the act of defying the truth mimicked by the theatrical violence represented on stage, which has the potential to stir the latent power of the theatre communion. I have used the theoretical work of Antonin Artaud, especially his “Theatre of Cruelty,” and the works of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Sarah Kane in conversation with Artaud’s theories as a prism through which to investigate my hypothesis. -

The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

The Theatre of the Real MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb i 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:32:40:32 PPMM MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim G INA MASUCCI MACK ENZIE THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiiiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM Copyright © 2008 by Th e Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKenzie, Gina Masucci. Th e theatre of the real : Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim / Gina Masucci MacKenzie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4 (cd-rom) 1. English drama—Irish authors—History and criticism—Th eory, etc. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Dramatic works. 3. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Dramatic works. 4. Sondheim, Stephen—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Th eater—United States—History— 20th century. 6. Th eater—Great Britain—History—20th century. 7. Ireland—Intellectual life—20th century. 8. United States—Intellectual life—20th century. I. Title. PR8789.M35 2008 822.009—dc22 2008024450 Th is book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4) Cover design by Jason Moore. Text design by Jennifer Forsythe. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Th omson-Shore, Inc. Th e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

An Artaudian and Brechtian Analysis of the Living Theatre's the Brig

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto An Artaudian and Brechtian Analysis of The Living Theatre’s The Brig: A Study of Contradictory Theories in Practice On a January evening in 1963 the stage director Julian Beck received a play entitled The Brig and immediately decided that it would be the next production his avant-garde troupe, The Living Theatre, was to produce. Written by Kenneth Brown, The Brig is a semi-autobiographical account of Brown’s harrowing experience in a Marine Corps prison while he was stationed at Mt. Fujiyama in Japan between 1954-1957.1 The production opened on May 15, 1963 under the direction of Beck’s wife and company co- founder, Judith Malina, and would ultimately become a signature work in The Living Theatre’s repertoire. Theatre critics readily recognized the piece’s use of a highly visceral and emotionally engaging theatrical form in dialectic conjunction with a socio/political content that attacked society’s various systems of hierarchical authority. New York Newsday described the performance as, “Shattering! Picasso’s Guernica or a Hiroronymous Bosch painting come to life,” while Variety magazine pointed out that it was “written with relentless fury…a searing indictment of man’s inhumanity to man.” The acclaimed theatre academic Robert Brustein perhaps captured the evening best when he wrote: An activist play designed to arouse responsibility…This ruthless documentary becomes an act of conscience, decency, and moral revolt in the midst of apathy and mass inertia. If you can spend a night in THE BRIG, you may start a jailbreak of your own.2 The Brig left its mark on the American theatre, as it was seminal in the development of the New York City avant-garde of the 1960s, and demonstrated The Living Theatre’s effective use of experimental performance as a source of political action. -

Women Surrealists: Sexuality, Fetish, Femininity and Female Surrealism

WOMEN SURREALISTS: SEXUALITY, FETISH, FEMININITY AND FEMALE SURREALISM BY SABINA DANIELA STENT A Thesis Submitted to THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to challenge the patriarchal traditions of Surrealism by examining the topic from the perspective of its women practitioners. Unlike past research, which often focuses on the biographical details of women artists, this thesis provides a case study of a select group of women Surrealists – chosen for the variety of their artistic practice and creativity – based on the close textual analysis of selected works. Specifically, this study will deal with names that are familiar (Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim, Frida Kahlo), marginal (Elsa Schiaparelli) or simply ignored or dismissed within existing critical analyses (Alice Rahon). The focus of individual chapters will range from photography and sculpture to fashion, alchemy and folklore. By exploring subjects neglected in much orthodox male Surrealist practice, it will become evident that the women artists discussed here created their own form of Surrealism, one that was respectful and loyal to the movement’s founding principles even while it playfully and provocatively transformed them. -

The Role of the Theatre Audience: a Theory of Production and Reception

THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE: A THEORY OF PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION By SUSAN BENNETT, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Parial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University January 1988 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Role of the Theatre Audience: A Theory of Production and Reception AUTHOR: Susan Bennett, B.A. (University of Kent at Canterbury) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Linda Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 389 ii ABSTRACT Th thesis examines the reception of theatrical performanc by their audience. Its starting points are (i) Brech s dramatic theory and practice, and (ii) theories 0 reading. These indicate the main emphases of the th ,is--theoretical approaches and performance practices, rather than the more usual recourse to dramatic ;xts. Beyond Brecht and reader-response criticism, other studies of viewing are explored. Both semiotics lnd post-structuralism have stimulated an intensity )f interest in theatrical communication and such inves ~gations provide an important impetus for my work. In suggesting a theory of reception in the theatre, examine _theatre's cultural status and the assumption underlying what we recognize as the theatrical event. The selection of a particular performanc is explored and from this, it is suggested that there _s an inevitable, inextricable link between the produc ~ve and receptive processes. The theory then looks to lore immediate aspects of the performance, including 1e theatre building (its geographic location, architectu 11 style, etc.), the performance itself, and the post-p :formance rituals of theatre-going. -

Librairie Le Galet

1 Librairie le galet FLORENCE FROGER 01 45 27 43 52 06 79 60 18 56 [email protected] DECEMBRE 2016 LITTERATURE - SCIENCES HUMAINES - BEAUX-ARTS Vente uniquement par correspondance Adresse postale : 18, square Alboni 75016 PARIS Conditions générales de vente : Les ouvrages sont complets et en bon état, sauf indications contraires. Nos prix sont nets. Les envois se font en colissimo : le port est à la charge du destinataire. RCS : Paris A 478 866 676 Mme Florence Froger IBAN : FR76 1751 5900 0008 0052 5035 256 BIC : CEPA FR PP 751 2 1 JORN (Asger). AFFICHES DE MAI 1968 : Brisez le cadre qi etouf limage / Aid os etudiants quil puise etudier e aprandre en libert / Vive la révolution pasioné de lintelligence créative / Pas de puissance dimagination sans images puisante. Paris, Galerie Jeanne Bucher. Collection complète des 4 affiches lithographiées en couleurs à 1000 exemplaires par Clot, Bramsen et Georges, et signées dans la pierre par Jorn. Ces affiches étaient destinées à couvrir les murs de la capitale. Parfait état. 1500 € 3 2 [AEROSTATION] TRUCHET (Jean- 6 [ANTI-FRANQUISME] VAZQUEZ Marc). L’AEROSTAT DIRIGEABLE. Une DE SOLA (Andrès). ALELUYAS DE LA vieille idée moderne… COLERA CONTRA LAS BASES Lagnieu, La Plume du temps, 2006. In-4, YANQUIS. broché, couverture illustrée, 119 pages. E.O. Nombreuses illustrations. 20 € Madrid, Supplément au n° 7-8 de Grand Ecart, 1962. Un feuillet A4 3 ALECHINSKY (Pierre), REINHOUD imprimé au recto, plié et TING. SOLO DE SCULPTURE ET DE en 4. Charge DIVERTISSEMENT arrangé pour peinture antifranquiste dénonçant la collaboration à quatre mains. militaire hispano-américaine. -

What Is a Dance? in 3 Dances, Gene Friedman Attempts to Answer Just That, by Presenting Various Forms of Movement. the Film Is D

GENE FRIEDMAN 3 Dances What is a dance? In 3 Dances, Gene Friedman attempts to answer just that, by presenting various forms of movement. The film is divided into three sections: “Public” opens with a wide aerial shot of The Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden and visitors walking about; “Party,” filmed in the basement of Judson Memorial Church, features the artists Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Robert Rauschenberg, and Steve Paxton dancing the twist and other social dances; and “Private” shows the dancer Judith Dunn warming up and rehearsing in her loft studio, accompanied by an atonal vocal score. The three “dances” encompass the range of movement employed by the artists, musicians, and choreographers associated with Judson Dance Theater. With its overlaid exposures, calibrated framing, and pairing of distinct actions, Friedman’s film captures the group’s feverish spirit. WORKSHOPS In the late 1950s and early 1960s, three educational sites were formative for the group of artists who would go on to establish Judson Dance Theater. Through inexpensive workshops and composition classes, these artists explored and developed new approaches to art making that emphasized mutual aid and art’s relationship to its surroundings. The choreographer Anna Halprin used improvisation and simple tasks to encourage her students “to deal with ourselves as people, not dancers.” Her classes took place at her home outside San Francisco, on her Dance Deck, an open-air wood platform surrounded by redwood trees that she prompted her students to use as inspiration. In New York, near Judson Memorial Church, the ballet dancer James Waring taught a class in composition that brought together different elements of a theatrical performance, much like a collage. -

Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion Oana Carmina Cimpean Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Cimpean, Oana Carmina, "Louis Aragon and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle: Servility and Subversion" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2283. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOUIS ARAGON AND PIERRE DRIEU LA ROCHELLE: SERVILITYAND SUBVERSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Oana Carmina Cîmpean B.A., University of Bucharest, 2000 M.A., University of Alabama, 2002 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 August, 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation advisor Professor Alexandre Leupin. Over the past six years, Dr. Leupin has always been there offering me either professional advice or helping me through personal matters. Above all, I want to thank him for constantly expecting more from me. Professor Ellis Sandoz has been the best Dean‘s Representative that any graduate student might wish for. I want to thank him for introducing me to Eric Voegelin‘s work and for all his valuable suggestions. -

Confrontation, Simulation, Admiration

Confrontation, Simulation, Admiration The Wooster Group’s Poor Theater Kermit Dunkelberg The punning title of The Wooster Group’s Poor Theater, shown as a work-in- progress in the spring and late fall of at the Performing Garage on Wooster Street in New York, invites many interpretations. Does it suggest the- atre that is: Poorly executed? Poorly funded? To be lamented? All of the above? Is this the Wooster Group’s retort to Grotowski’s “poor theatre” of reduced means and monastic discipline (Grotowski ), or their own version of it? The Wooster Group’s self-mocking, reverent/irreverent, high-tech/low-tech, nostalgic/derisive production questions the state of contemporary performance by trying on the styles of a vanished group (the Polish Laboratory Theatre, dis- solved in ) and a vanishing one (the Ballett Frankfurt, disbanded in August —half a year after Poor Theater had its first showing). My focus in this article is on the sections of Poor Theater that deal with Grotowski’s Polish Laboratory Theatre (–). I see the Wooster Group’s production in light of the history of reception/rejection/appropriation of Grotowski’s work in the United States. In the wake of Grotowski’s first American workshop at New York University in , Richard Schechner founded The Performance Group. In the mid-s, the Wooster Group grew out of The Performance Group, be- coming an independent entity in . Poor Theater is in part a confrontation with an ancestor. In the spring program, “The Director” noted the importance of ancestors: The writers, the great writers of the past, have been very important to me, even if I have struggled against them. -

Sretenovic Dejan Red Horizon

Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON EDITION Red Publications Dejan Sretenović RED HORIZON AVANT-GARDE AND REVOLUTION IN YUGOSLAVIA 1919–1932 kuda.org NOVI SAD, 2020 The Social Revolution in Yugoslavia is the only thing that can bring about the catharsis of our people and of all the immorality of our political liberation. Oh, sacred struggle between the left and the right, on This Day and on the Day of Judgment, I stand on the far left, the very far left. Be‑ cause, only a terrible cry against Nonsense can accelerate the whisper of a new Sense. It was with this paragraph that August Cesarec ended his manifesto ‘Two Orientations’, published in the second issue of the “bimonthly for all cultural problems” Plamen (Zagreb, 1919; 15 issues in total), which he co‑edited with Miroslav Krleža. With a strong dose of revolutionary euphoria and ex‑ pressionistic messianic pathos, the manifesto demonstrated the ideational and political platform of the magazine, founded by the two avant‑garde writers from Zagreb, activists of the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia, after the October Revolution and the First World War. It was the struggle between the two orientations, the world social revolution led by Bolshevik Russia on the one hand, and the world of bourgeois counter‑revolution led by the Entente Forces on the other, that was for Cesarec pivot‑ al in determining the future of Europe and mankind, and therefore also of the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Cro‑ ats and Slovenes (Kingdom of SCS), which had allied itself with the counter‑revolutionary bloc. -

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746

The Inventory of the Sam Shepard Collection #746 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Shepard, Srun Sept,1~77 - Jan,1979 Outline of Inventory I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays B. Poetry c. Journal D. Short Prose E. Articles F. Juvenilia G. By Other Authors II. NOTES III. PRINTED MATTER A, By SS B. Reviews and Publicity C. Biographd:cal D. Theatre Programs and Publicity E. Miscellany IV. AWARDS .•, V. FINANCIAL RECOR.EB A. Receipts B. Contracts and Ageeements C. Royalties VI. DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS VII. CORRESPONDENCE VIII.TAPE RECORDINGS Shepard, Sam Box 1 I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Plays 1) ACTION. Produced in 1975, New York City. a) Typescript with a few bolo. corr. 2 prelim. p., 40p. rn1) b) Typescript photocopy of ACTION "re-writes" with holo. corr. 4p. marked 37640. (#2) 2) ANGEL CITY, rJrizen Books, 1976. Produced in 1977. a) Typescript with extensive holo. corr. and inserts dated Oct. 1975. ca. 70p. (ft3) b) Typescript with a few holo. corr. 4 prelim. p., 78p. (#4) c) Typescript photocopy with holo. markings and light cues. Photocopy of r.ouqh sketch of stage set. 1 prelim. p., 78p. ms) 3) BURIED CHILD a) First draft, 1977. Typescript with re~isions and holo. corr. 86p. (#6) b) Typescript revisions. 2p. marked 63, 64. (#6) 4) CALIFORNIA HEART ATTACK, 1974. ,•. ' a) Typescript with holo. corr. 23p. (#7) ,, 5) CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS, Urizen Books, 1976. a) Typescript with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p., 104p. ms) b) Typescript photocopy with holo. corr. 1 prelim. p. 104p. (#9) c) Typescript dialogue and stage directions, 9p. numbered 1, 2, and 2-8. -

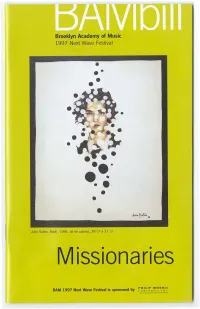

Missionaries

Brooklyn Academy of Music 1997 Next Wave Festival .•- •• • •••••• ••• • • • • Julio Galan, Rado, 1996, oil on canvas, 39 '/>" x 31 W' Missionaries PHILIP MORRIS BAM 1997 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by COMPANIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Harvey Lichtenstein President and Executive Producer presents Missionaries Running time: BAM Majestic Theater approximately November 4-8, 1997 at 7:30pm two hours and twenty minutes Conceived, composed and directed by Elizabeth Swados including one intermission Produced by Ron Kastner, Peter Manning and New York Stage and Film Cast Dorothy Abrahams, Vanessa Aspillaga, Carrie Crow, Josie de Guzman, Pierre Diennet, Marisa Echeverria, Abby Freeman, Peter Kim, Gretchen Lee Krich, Fabio Polanco, Nick Petrone, Heather Ramey, Nina Shreiber, Tina Stafford, Rachel Stern, Amy White Musical direction and piano David Gaines Percussion Genji Ito, Bill Ruyle Guitar Ramon Taranco Cello / keyboards J. Michael Friedman Lighting design Beverly Emmons Costu me design Kaye Voyce Production manager Jack O'Connor General manager Christina Mills Production stage manager Judy Tucker Co-commissioned by Brooklyn Academy of Music Major support provided by ==:ATaaT and The Ford Foundation ~ Missionaries is meant to honor the memory of those who were killed in EI Salvador during the terrible times of the 1970s and 1980s. I hope it will also bring attention to the extraordinary efforts being made today by the MADRES and other groups devoted to stopping violence and bringing freedom and dignity to the poor. Jean Donovan, Dorothy Kazel, Ita Ford, and Maura Clarke were murdered because of their beliefs and dedication to the women and children of EI Salvador.