Teaching Tolerance • Speak up at School & Responding to Hate and Bias at School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.13. La Llei Dels Drets Civils I Del Dret a Vot 13

Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Treball de fi de grau Títol Autor/a Tutor/a Grau Data Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Facultat de Ciències de la Comunicació Full Resum del TFG Títol del Treball Fi de Grau: Autor/a: Tutor/a: Any: Titulació: Paraules clau (mínim 3) Català: Castellà: Anglès: Resum del Treball Fi de Grau (extensió màxima 100 paraules) Català: Castellà: Anglès Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story.” James Baldwin Agraïments A Cristina Cifuentes i a Bob l’Estatut 1. INTRODUCCIÓ 4 2. MARC TEÒRIC 5 2.1. L’ESCLAVISME 5 2.2. LA GUERRA DE SECESSIÓ 5 2.3. LA RECONSTRUCCIÓ 6 2.4. L’IMPERI JIM CROW 7 2.5. L’ESTIU VERMELL DE 1919 8 2.6. LA GRAN DEPRESSIÓ 9 2.7. LA SEGONA GUERRA MUNDIAL 9 2.8. DESPRÉS DE LA II GUERRA MUNDIAL 10 2.9. L’INCIPIENT MOVIMENT 11 2.10. EL MOVIMENT I LA NO-VIOLÈNCIA 11 2.11. EL MOVIMENT ES CONSOLIDA 12 2.12. LA MARXA SOBRE WASHINGTON 13 2.13. LA LLEI DELS DRETS CIVILS I DEL DRET A VOT 13 2.14. EL PODER NEGRE 14 2.15. L’ASSASSINAT DEL LÍDER 16 2.16. L’ORFANDAT 17 3. METODOLOGIA 18 3.1. OBJECTE D’ESTUDI 18 3.2. OBJECTIUS 18 3.3. PREGUNTES D’INVESTIGACIÓ 18 3.4. MÈTODE 18 3.5. MOSTRA 21 3.6. LIMITACIONS 22 4. INVESTIGACIÓ 23 4.1. ANÀLISI MOSTRA GENERAL 23 4.2. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY of NONVIOLENT PEACEBUILDING MATERIALS (2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2015, 2017 Merged Publication)

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NONVIOLENT PEACEBUILDING MATERIALS (2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2015, 2017 Merged Publication) Compiled by Citizens for Peace: www.Citizens4rpeace.com Many of these materials are available through your Library Network, which includes over 75 communities or through MeLCat--a Statewide database. Purpose: The purpose of the Peacebuilding Bibliography is to gather and make accessible, for youth and adults, materials that document efforts for nonviolent social change and nonviolent conflict resolution between peoples and nations. Scope: The Bibliography contains information on peace movements, both historical and current; leaders of nonviolence; and Nobel Peace Prize winners. In addition, there is information on nonviolent solutions to conflict as well as information on inspirational leaders dedicated to improving the lives of people through economic and social change. Sources: Sources used in the data gathering for this Bibliography includes: The United States Institute of Peace Library, Washington D.C.; Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania, Peace Collection; Professor Irwin Abrams (Emeritus), Antioch College, Ohio, Nobel Peace Prize Archivist; collectors of women’s peace movement documented history; The Jane Addams Peace Association (JAPA), an affiliate of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF); International Institute for Restorative Practice (iirp), various peace organizations; members of Citizens for Peace; and lastly, Amazon for their online system of listing books on related subjects. It is the intention that this Peacebuilding collection be an ongoing project with the inclusion of additional materials, as they become known. This Bibliography contains listings of materials and is a compilation of previous lists of 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2015 and 2017 addendums. The key for identifying materials is listed on the bottom of each page. -

Racial Equity Resource Guide

RACIAL EQUITY RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 7 An Essay by Michael R. Wenger 17 Racial Equity/Racial Healing Tools Dialogue Guides and Resources Selected Papers, Booklets and Magazines Racial Equity Toolkits and Guides to Action Workshops, Convenings and Training Curricula 61 Anchor Organizations 67 Institutions Involved in Research on Structural Racism 83 National Organizing and Advocacy Organizations 123 Media Outreach Traditional Media Social Media 129 Recommended Articles, Books, Films, Videos and More Recommended Articles: Structural/Institutional Racism/Racial Healing Recommended Books Recommended Sources for Documentaries, Videos and Other Materials Recommended Racial Equity Videos, Narratives and Films New Orleans Focused Videos Justice/Incarceration Videos 149 Materials from WKKF Convenings 159 Feedback Form 161 Glossary of Terms for Racial Equity Work About the Preparer 174 Index of Organizations FOREWORD TO THE AMERICA HEALING COMMUNITY, When the W.K. Kellogg Foundation launched America Healing, we set for ourselves the task of building a community of practice for racial healing and equity. Based upon our firm belief that our greatest asset as a foundation is our network of grantees, we wanted to link together the many different organizations whose work we are now supporting as part of a broad collective to remove the racial barriers that limit opportunities for vulnerable children. Our intention is to ensure that our grantees and the broader community can connect with peers, expand their perceptions about possibilities for their work and deepen their understanding of key strategies and tactics in support of those efforts. In 2011, we worked to build this community We believe in a different path forward. -

1927/28 - 2007 Гг

© Роман ТАРАСЕНКО. г. Мариуполь 2008г. Украина. [email protected] Лауреаты премии Американской Академии Киноискусства «ОСКАР». 1927/28 - 2007 гг. 1 Содержание Наменование стр Кратко о премии………………………………………………………. 6 1927/28г……………………………………………………………………………. 8 1928/29г……………………………………………………………………………. 9 1929/30г……………………………………………………………………………. 10 1930/31г……………………………………………………………………………. 11 1931/32г……………………………………………………………………………. 12 1932/33г……………………………………………………………………………. 13 1934г……………………………………………………………………………….. 14 1935г……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 1936г……………………………………………………………………………….. 16 1937г……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 1938г……………………………………………………………………………….. 18 1939г……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 1940г……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 1941г……………………………………………………………………………….. 21 1942г……………………………………………………………………………….. 23 1943г……………………………………………………………………………….. 25 1944г……………………………………………………………………………….. 27 1945г……………………………………………………………………………….. 29 1946г……………………………………………………………………………….. 31 1947г……………………………………………………………………………….. 33 1948г……………………………………………………………………………….. 35 1949г……………………………………………………………………………….. 37 1950г……………………………………………………………………………….. 39 1951г……………………………………………………………………………….. 41 2 1952г……………………………………………………………………………….. 43 1953г……………………………………………………………………………….. 45 1954г……………………………………………………………………………….. 47 1955г……………………………………………………………………………….. 49 1956г……………………………………………………………………………….. 51 1957г……………………………………………………………………………….. 53 1958г……………………………………………………………………………….. 54 1959г……………………………………………………………………………….. 55 1960г………………………………………………………………………………. -

Selma the Bridge to the Ballot

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

A Great Spot to Gather. for All Ages. to Celebrate Weddings, Birthdays And

January 2013 • Calendar of Events • Map, Inns, B&B’s • Dining, Real Estate • Entertainment • Book Reviews • Plenty of Good Free Reading! X-C SKIING • SNOWSHOEING • 1,300 ACRES FITNESS CENTER • SAUNA WHIRLPOOL • GOLF BIKING A great spot to gather. For all ages. To celebrate weddings, birthdays and family reunions. An Outstanding Place to Connect. ~ Only 3 miles from Exit 4 / I-89 ~ 802-728-5575 www.ThreeStallionInn.com Lower Stock Farm Road Randolph, Vermont The Sammis Family, Owners WEDDINGS • REUNIONS RETREATS • CONFERENCES “THE BEST BED & BREAKFAST IN CENTRAL VERMONT” Musicians gather for the Northern Roots Traditional Music Festival in Brattleboro, VT. This year the event takes place January 26. photo by Pam Lierle Brattleboro Music Center Presents Winter Concerts And Performances for all Tastes A Christian Resale Shop Concert Choir: Towards the Light Windham Orchestra: Psalms & Fireworks Located in the St. Edmund of Canterbury Church Basement The Brattleboro Concert Choir, under the direction of The choruses of all four Windham County High Schools Main Street, Saxtons River, VT Susan Dedell, presents Morten Lauridsen’s Lux Aeterna, and join the Windham Orchestra under the direction of Maestro Open Thurs & Sat 9 am to 3 pm Bob Chilcott’s Requiem. There will be two performances— Director Hugh Keelan to present Stravinsky’s masterpiece Saturday, January 12, 7:30 pm, First Baptist Church, Brattle- Symphony of Psalms. There ail be two performances—Fri- boro, VT; and Sunday January 13, 3 pm, First Baptist Church, day, January 25, at 7:30 p.m., at Bellows Falls Union High ROCKINGHAM ARTS AND Brattleboro, VT. Tickets are $15 adults, $10 students. -

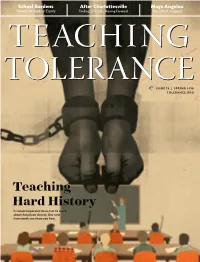

Teaching Hard History It’S More Important Than Ever to Teach About American Slavery

School Gardens After Charlottesville Maya Angelou Sowing the Seeds of Equity Finding Strength, Moving Forward The Life of a Legend TTEEAACCHIHINNGG T OLERANCE ISSUE 58 | SPRING 2018 TOLERANCETOLERANCE.ORG Teaching Hard History It’s more important than ever to teach about American slavery. Our new framework can show you how. FREE WHAT CAN THE NEW TOLERA NCE.ORG DO FOR YOU? LEARNING PLANS GRADES K-12 EDUCATING FOR A DIVERSE DEMOCRACY Discover and develop world-class materials with a community of educators committed to diversity, equity and justice. You can now build and customize a FREE learning plan based on any Teaching Tolerance article! TEACH THIS 1 Choose an article. 2 Choose an essential question, tasks and strategies. 3 Name, save and print your plan. 4 Teach original TT content! BRING SOCIAL JUSTICE WHAT CAN THE NEW TOLERA NCE.ORG DO FOR YOU? TO YOUR CLASSROOM. TRY OUR FILM KITS SELMA: THE BRIDGE TO THE BALLOT The true story of the students and teachers who fought to secure voting rights for African Americans in the South. Grades 6-12 Gerda Weissmann was 15 when the Nazis came for her. ONE SURVIVOR They took all but her life. REMEMBERS Gerda Weissmann Klein’s account of surviving the ACADEMY AWARD® Holocaust encourages WINNER BEST DOCUMENTARY SHORT SUBJECT Teaching Tolerance and The gerda and kurT klein foundaTion presenT thoughtful classroom discussion about a A film by Kary Antholis l CO-PRODUCED BY THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM AND HOME BOX OFFICE difficult-to-teach topic. Grades 6-12 streaming online THE STORY of CÉSAR CHÁVEZ and a GREAT MOVEMENT for SOCIAL JUSTICE VIVA LA CAUSA MEETS CONTENT STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES AND LANGUAGE VIVA LA CAUSA ARTS, GRADES 7-12. -

ROCK & ROLL and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Cheryl LS Baer a Thesis/Project Presented to the Facult

CONCURRENT REVOLUTIONS: ROCK & ROLL AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Cheryl LS Baer A Thesis/Project Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Sciences Teaching American History May 2005 CONCURRENT REVOLUTIONS: ROCK & ROLL AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Cheryl LS Baer Approved by the Master’s Thesis Committee: Delores McBroome, Major Professor Date Rod Sievers, Committee Member Date Gayle Olson-Raymer, Committee Member Date Delores McBroome, Graduate Coordinator, Date MASS- - Teaching American History Cohort Donna E. Schafer, Dean for Research and Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Rock & Roll burst upon the scene at the same time the Civil Rights Movement picked up momentum in the 1950s. While one might claim this was just a happy coincidence, it was actually a logical progression in music influenced by the same factors pushing the Civil Rights Movement forward. World War II, technology, migration of workers to urban centers, prosperity, and social anxiety of a changing society all affected the development of Rock & Roll and Civil Rights. Philip Ennis, author of The Seventh Stream: The Emergence of Rocknroll, Alan Dundes, in his book, Interpreting Folklore, and Reebee Garofalo, author of “Popular Music and the Civil Rights Movement” all present arguments that music both reflects and influences the social interactions and social movements of a period. Rock & Roll in the 1950s and 1960s expresses the social anxieties of the Civil Rights Movement. Ennis theorizes that Rock & Roll was the natural consequence of World War II and its aftermath as technology forged ahead impacting the arts, economics and politics of post- war America. -

Preventing Youth Hate Crime

PREVENTING YOUTH HATE CRIME A Manual For Schools And Communities INTRODUCTION The term "hate crime" is defined by various federal and state laws. In its broadest sense, the term refers to an attack on an individual or his or her property (e.g., vandalism, arson, assault, murder) in which the victim is intentionally selected because of his or her race, color, religion, national origin, gender, disability, or sexual orientation. Every year, thousands of Americans are victims of such hate crimes. Each one of these crimes has a ripple effect in our communities. The pain and injustice of such crimes tear at the fabric of our democratic society, creating fear and tensions that ultimately affect us all. Schools are not immune from such intolerance and violence. Teenagers and young adults account for a significant proportion of the country's hate crimes-both as perpetrators and as victims. Hate-motivated behavior, whether in the form of ethnic conflict, harassment, intimidation, or graffiti, is often apparent on school grounds. Hate violence is also perpetrated by hate groups, which actively work to recruit young people to their ranks. The good news is that children are not born with such attitudes; they are learned. It is possible for schools, families, law enforcement, and communities to work together to prevent the development of the prejudiced attitudes and violent behavior that lead to hate crimes. Prejudice and the resulting violence can be reduced or even eliminated by instilling in children an appreciation and respect for each other's differences, and by helping them to develop empathy, conflict resolution, and critical thinking skills. -

Annotated Bibliography of Sources

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SOURCES *Unless otherwise noted, the following reviews were taken from Great Reads Shelf (http://www.goodreads.com/genres/great-reads). BIOGRAPHY Diane Nash: The Fire of the Civil Rights Movement: A Biography. Mullins, Lisa (author). Jan, 2007. 104p. Barnhardt & Ashe Pub, hardcover. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Ransby, Barbara (author). Feb. 2005. 496p. Univ. of North Carolina Press, paperback. One of the most important African American leaders of the twentieth century and perhaps the most influential woman in the civil rights movement, Ella Baker (1903-1986) was an activist whose remarkable career spanned fifty years and touched thousands of lives. Ella Baker: Freedom Bound. Grant, Joanne, Igor Ed. Grant, Julian Bond (author). Jan, 1999. 288p. John Wiley & Sons, paperback. "Splendid biography . a valuable contribution to the growing body of literature on the critical roles of women in civil rights."--Joyce A. Ladner, The Washington Post Book World "The definitive biography of Ella Baker, a force behind the civil rights movement and almost every social justice movement of this century."--Gloria Steinem "This book will be received with plaudits for its empathy, insightfulness, and gendered narration of an astonishingly neglected life that was pivotal in the pursuit of American justice and humanity."--David Levering Lewis Pulitzer Prize-winning author of W. E. B. Du Bois A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Manis, Andrew M. (author). Oct, 2001. 576. Univ. of Alabama Press, paperback. This first biography of Fred Shuttlesworth-winner of both the 2000 Lillian Smith Award and the 2001 James F. -

Teachers Are Taking Fresh Approaches to Make Gym More Fun for Everyone

The N-WORD TEACHER BULLIES WE j ART! Too tough to teach? Spot them. Stop them. Help them. And it’s not an extra TEACTWENTIETH A NNIVERSARYHI INGSSUE TOTOLERANCE.ORG LERANRANCEissue 40 | Fall 2011 THE NEW PHYSICAL EDUCATION GAME CHANGERS Teachers are taking fresh approaches to make gym more fun for everyone A ClAssiC Film, DigitAlly RestoReD AnD with new lessons, is AgAin AvAilAble FoR AmeRiCA’s ClAssRooms • ACADemy AwARD® WINNER FOR SHORT DOCUMENTARY, 1994 FREE TO TEACHERS GRADES 6-12 TEACHING TOLERANCE PRESENTS A Time for Justice america’s civil rights movement “It wasn’t no Civil War. Wasn’t no world war. Just people in the same country, fighting each other.” A ClAssiC Film, DigitAlly RestoReD AnD with new lessons, is AgAin AvAilAble FoR AmeRiCA’s ClAssRooms • ACADemy AwARD® WINNER FOR SHORT DOCUMENTARY, 1994 In A Time for Justice, four-time Academy Award®-winning filmmaker Charles Guggenheim captured the spirit of the civil rights movement through historical footage and the voices of those who participated in the struggle. Narrated by Julian Bond and featuring Rep. John Lewis, the 38-minute film al- lows today’s generation of students to witness firsthand the movement’s most dramatic moments—the bus boycott in Montgomery, the school crisis in Little Rock, the violence in Birmingham and the triumphant 1965 march for voting rights. “This concise, dramatic history captures for today’s students the idealist courage that KIT INCLUDES sustained the civil • 38-minute film on DVD rights movement …” Taylor Branch, • New teacher’s guide with