Courtship, Hostile Behavior, Nest-Establishment and Egg Laying in the Eared Grebe (Podiceps Caspicus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

Breeding of the Leach's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma Leucorhoa at Santa Catalina Island, California

Carter et al.: Leach’s Storm-Petrel at Santa Catalina Island 83 BREEDING OF THE LEACH’S STORM-PETREL OCEANODROMA LEUCORHOA AT SANTA CATALINA ISLAND, CALIFORNIA HARRY R. CARTER1,3,4, TYLER M. DVORAK2 & DARRELL L. WHITWORTH1,3 1California Institute of Environmental Studies, 3408 Whaler Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA 2Catalina Island Conservancy, 125 Clarissa Avenue, Avalon, CA 90704, USA 3Humboldt State University, Department of Wildlife, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, USA 4Current address: Carter Biological Consulting, 1015 Hampshire Road, Victoria, BC V8S 4S8, Canada ([email protected]) Received 4 November 2015, accepted 5 January 2016 Among the California Channel Islands (CCI) off southern California, Guadalupe Island, off central-west Baja California (Ainley 1980, the Ashy Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma homochroa (ASSP) is the Power & Ainley 1986, Ainley 2005, Pyle 2008, Howell et al. most numerous and widespread breeding storm-petrel; it is known 2009). Alternatively, these egg specimens may have been from to breed at San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, and dark-rumped LESP, which are known to breed at the Coronado San Clemente islands (Hunt et al. 1979, 1980; Sowls et al. 1980; and San Benito islands, Baja California (Ainley 1980, Power & Carter et al. 1992, 2008; Harvey et al. 2016; Fig. 1B; Appendix 1, Ainley 1986). available on the website). Low numbers of Black Storm-Petrels O. melania (BLSP) also breed at Santa Barbara Island (Pitman Within this context, we asked the following questions: (1) Were the & Speich 1976; Hunt et al. 1979, 1980; Carter et al. 1992; 1903 egg records the first breeding records of LESP at Catalina and Appendix 1). -

(82) FIELD NOTES on the LITTLE GREBE. the Following Observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps R. Ruficollis) Were Made at Fetch

(82) FIELD NOTES ON THE LITTLE GREBE. BY P. H. TRAHAIR HARTLEY. THE following observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps r. ruficollis) were made at Fetcham Pond, near Leatherhead, in Surrey, during the last three years. TERRITORY. Little Grebes begin to defend territories in the middle of February. These are small areas—about |- acre—situated in the parts of the very shallow lake that are overgrown with marestail (Hippuris vulgaris). Where several territories border on an open space, free from weeds, this constitutes a neutral area where paired birds can meet and associate with others, without fighting. The actual territories are strictly protected. Both sexes defend their borders, sometimes working together. Terri torial demonstrations-—far more often than not they do not end in actual fighting—take place many times daily between pairs whose marches adjoin. One bird makes a series of short rushes towards his neighbours' territory, flapping his raised wings, and keeping his head and neck outstretched ; at the same time he utters the shrill, tittering call. The owner of the territory advances in the same set style ; between each rush, both birds float with heads drawn in, flank feathers fluffed out, and wings slightly raised. So they approach each other, until they float about a foot apart, and strictly on the territorial border. As they face one another, I have seen one, or both birds peck with an almost nervous movement at the surface of the water, as though picking something up. On one occasion the bird which had started the encounter splashed the water with its beak, and snatched at a weed stem. -

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED by the FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOL. 37, NO. 4 NOVEMBER 2009 PAGES 115-170 Florida Field Naturalist 37(4):115-120, 2009. FIRST RECORD OF LEAST GREBES (Tachybaptus dominicus) NESTING IN FLORIDA LEE M. HASSE AND O. DAVID HASSE 398 N.E. 24th Street, Boca Raton, Florida 33431 The Least Grebe (Tachybaptus dominicus), the smallest New World member of the grebe family (Podicipedidae), occurs from the southwestern United States and Mexico to Chile, Argentina and in the West Indies (Trinidad, Tobago, the Bahamas, and Greater Antilles; Ogilvie and Rose 2003). This is a plump grebe with yellowish eyes, a thin bill, and fluffy white tail coverts, ranging in length from 22-27 cm (8.25-10.5 inches). In basic plumage Least Grebes are brownish to blackish above with a white throat; in alternate plumage the throat is black. Their wetland habitats are varied and include fresh and brack- ish ponds, lakes, slow-flowing rivers, and mangrove swamps that have good vegetative cover along the edges. There are reports of nesting in temporary bodies of water (Storer 1992). Their compact floating nest is made of aquatic vegetation and anchored to rooted plants. The eggs are incubated by both adults and hatch in about 21 days (Palmer 1962). The Least Grebe is reported to nest year-round in the tropics. Although considered non-migratory, they have been found to move long distances (Storer 1992). Norton et al. (2009) report that the Least Grebe has been expanding its range in the Greater and Lesser Antilles in the last de- cade. -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Little Grebe

A CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF SAADANI. Little Grebe Black-chested Snake Eagle Redshank Little Swift White Pelican Bateleur Terek Sandpiper Eurasian Swift Pink-backed Pelican African Goshawk Sanderling White-rumped Swift Long-tailed Cormorant Steppe Eagle Curlew Sandpiper Palm Swift Darter Tawny Eagle Little Stint Bohm's Spinetail Little Bittern Augur Buzzard Black-tailed Godwit Speckled Mousebird Grey Heron Lizard Buzzard Ruff Blue-naped Mousebird Goliath Heron Pale Chanting Goshawk Turnstone Narina Trogon Cattle Egret Martial Eagle Black-winged Stilt Pied Kingfisher Green-backed Heron Crowned Eagle Avocet Malachite Kingfisher Great White Egret Fish Eagle Water Thicknee Brown-hooded Kingfisher Black Heron Black Kite Temminck's Courser Striped Kingfisher Little Egret Osprey Lesser Black-backed Gull Chestnut-bellied Kingfisher Yellow-billed Egret African Hobby White-winged Black Tern Mangrove Kingfisher Night Heron Hobby Gull-billed Tern Pygmy Kingfisher Hamerkop Kestrel Little Tern White-throated Bee-eater Open-billed Stork Red-necked Spurfowl Lesser Crested Tern Eurasian Bee-eater Woolly-necked Stork Crested Francolin Swift Tern Swallow-tailed Bee-eater Yellow-billed Stork Crested Guineafowl Caspian Tern Northern Carmine Bee-eater Hadada Ibis Helmeted Guineafowl Common Tern Blue-cheeked Bee-eater Sacred Ibis Black Crake Ring-necked Dove Little Bee-eater African Spoonbill Black-bellied Bustard Red-eyed Dove Madagascar Bee-eater Lesser Flamingo Jacana Emerald-spotted Wood Dove Lilac-breasted Roller Greater Flamingo Ringed Plover Tambourine -

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and Area

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and area Reproduced with kind permission of Etienne Marais of Indicator Birding Visit www.birding.co.za for more info and details of birding tours and events Endemic birds KEY: SA = South African Endemic, SnA = Endemic to Southern Africa, NE = Near endemic (Birders endemic) to the Southern African Region. RAR = Rarity Status KEY: cr = common resident; nr = nomadic breeding resident; unc = uncommon resident; rr = rare; ? = status uncertain; s = summer visitor; w = winter visitor r Endemicity Numbe Sasol English Status All Scientific p 30 Little Grebe cr Tachybaptus ruficollis p 30 Black-necked Grebe nr Podiceps nigricollis p 56 African Darter cr Anhinga rufa p 56 Reed Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax africanus p 56 White-breasted Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax lucidus p 58 Great White Pelican nr Pelecanus onocrotalus p 58 Pink-backed Pelican ? Pelecanus rufescens p 60 Grey Heron cr Ardea cinerea p 60 Black-headed Heron cr Ardea melanocephala p 60 Goliath Heron cr Ardea goliath p 60 Purple Heron uncr Ardea purpurea p 62 Little Egret uncr Egretta garzetta p 62 Yellow-billed Egret uncr Egretta intermedia p 62 Great Egret cr Egretta alba p 62 Cattle Egret cr Bubulcus ibis p 62 Squacco Heron cr Ardeola ralloides p 64 Black Heron uncs Egretta ardesiaca p 64 Rufous-bellied Heron ? Ardeola rufiventris RA p 64 White-backed Night-Heron rr Gorsachius leuconotus RA p 64 Slaty Egret ? Egretta vinaceigula p 66 Green-backed Heron cr Butorides striata p 66 Black-crowned Night-Heron uncr Nycticorax nycticorax p -

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

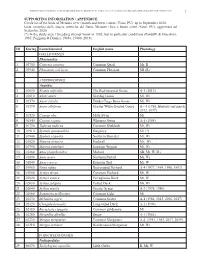

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p. -

A Synopsis of the Pre-Human Avifauna of the Mascarene Islands

– 195 – Paleornithological Research 2013 Proceed. 8th Inter nat. Meeting Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution Ursula B. Göhlich & Andreas Kroh (Eds) A synopsis of the pre-human avifauna of the Mascarene Islands JULIAN P. HUME Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Tring, UK Abstract — The isolated Mascarene Islands of Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues are situated in the south- western Indian Ocean. All are volcanic in origin and have never been connected to each other or any other land mass. Despite their comparatively close proximity to each other, each island differs topographically and the islands have generally distinct avifaunas. The Mascarenes remained pristine until recently, resulting in some documentation of their ecology being made before they rapidly suffered severe degradation by humans. The first major fossil discoveries were made in 1865 on Mauritius and on Rodrigues and in the late 20th century on Réunion. However, for both Mauritius and Rodrigues, the documented fossil record initially was biased toward larger, non-passerine bird species, especially the dodo Raphus cucullatus and solitaire Pezophaps solitaria. This paper provides a synopsis of the fossil Mascarene avifauna, which demonstrates that it was more diverse than previously realised. Therefore, as the islands have suffered severe anthropogenic changes and the fossil record is far from complete, any conclusions based on present avian biogeography must be viewed with caution. Key words: Mauritius, Réunion, Rodrigues, ecological history, biogeography, extinction Introduction ily described or illustrated in ships’ logs and journals, which became the source material for The Mascarene Islands of Mauritius, Réunion popular articles and books and, along with col- and Rodrigues are situated in the south-western lected specimens, enabled monographs such as Indian Ocean (Fig. -

FEEDING BEHAVIOR of the LEAST GREBE (Tachybaptus Dominicus) UPON NEOTROPICAL RANIDS in COSTA RICA

Florida Field Naturalist 44(2):59-62, 2016. FEEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE LEAST GREBE (Tachybaptus dominicus) UPON NEOTROPICAL RANIDS IN COSTA RICA VÍCTOR J. ACOSTA-CHavES1,2,3 AND DANIEL JIMÉNEZ3 1Fundación Rapaces de Costa Rica, P.O. Box 1626-3000 Heredia, Costa Rica 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, Costa Rica E–mail: [email protected] 3Unión de Ornitólogos de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica Avian predation on amphibians can be considered an important evolutionary force for both taxa, and its documentation helps to elucidate aspects of evolution, ecology, and even conservation (Shea 1987, Wells 2010). But because these interactions are difficult to observe and quantify, the role of amphibians as dietary items of birds is still barely known in the Neotropics (Acosta and Morún 2014). For example, even when grebes (Podicipedidae) have been anecdotally reported to prey on aquatic amphibians (Shea 1987, Stiles and Skutch 1989, Kloskowski et al. 2010), data on habitat selection, diet, and feeding behavior of grebes are primarily from Old World and Nearctic regions (e.g., Shea 1987, Forbes and Sealy 1990, Wiersma et al. 1995, Kloskowski et al. 2010). In Neotropical areas, such as Costa Rica, both natural and artificial lagoons and ponds provide habitat for waterbirds, including grebes (Stiles and Skutch 1989). The Least Grebe (Tachybaptus dominicus) is a widespread waterbird ranging from the southern United States of America to northern Argentina, including the Bahamas and Greater Antilles. In Costa Rica the subspecies T. d. brachypterus is distributed from lowlands to 1525 m ASL, but it is most common in the Central Valley and San Vito Region (Stiles and Skutch 1989).