A Dam, Regional Chauvinism, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Know-More-About-Wayanad.Pdf

Imagine a land blessed by the golden hand of history, shrouded in the timeless mists of mystery, and flawlessly Wayanad adorned in nature’s everlasting splendor. Wayanad, with her enchanting vistas and captivating Way beyond… secrets, is a land without equal. And in her embrace you will discover something way beyond anything you have ever encountered. 02 03 INDEX Over the hills and far away…....... 06 Footprints in the sands of time… 12 Two eyes on the horizon…........... 44 Untamed and untouched…........... 64 The land and its people…............. 76 04 05 OVER THE ayanad is a district located in the north- east of the Indian state of Kerala, in the southernmost tip of the WDeccan Plateau. The literal translation of “Wayanad” is HILLS AND “Wayal-nad” or “The Land of Paddy Fields”. It is well known for its dense virgin forests, majestic hills, flourishing plantations and a long standing spice trade. Wayanad’s cool highland climate is often accompanied by sudden outbursts of torrential rain and rousing mists that blanket the landscape. It is set high on the majestic Western Ghats with altitudes FAR AWAY… ranging from 700 to 2100 m. Lakkidi View Point 06 07 Wayanad also played a prominent role district and North Wayanad remained The primary access to Wayanad is the Thamarassery Churam (Ghat Pass) in the history of the subcontinent. It with Kannur. By amalgamating North infamous Thamarassery Churam, which is often called the spice garden of the Wayanad and South Wayanad, the is a formidable experience in itself. The south, the land of paddy fields, and present Wayanad district came into official name of this highland passage is the home of the monsoons. -

IDRB Report.Pdf

Irrigation Department Government of Kerala PERFORMANCE PROGRESSION POLICIES Irrigation Design and Research Board November 2020 PREFACE Water is a prime natural resource, a basic human need without which life cannot sustain. With the advancement of economic development and the rapid growth of population, water, once regarded as abundant in Kerala is becoming more and more a scarce economic commodity. Kerala has 44 rivers out of which none are classified as major rivers. Only four are classified as medium rivers. All these rivers are rain-fed (unlike the rivers in North India that originate in the glaciers) clearly indicating that the State is entirely dependent on monsoon. Fortunately, Kerala receives two monsoons – one from the South West and other from the North East distributed between June and December. Two-thirds of the rainfall occurs during South West monsoon from June to September. Though the State is blessed with numerous lakes, ponds and brackish waters, the water scenario remains paradoxical with Kerala being a water –stressed State with poor water availability per capita. The recent landslides and devastating floods faced by Kerala emphasize the need to rebuild the state infrastructure ensuring climate resilience and better living standards. The path to be followed to achieve this goal might need change in institutional mechanisms in various sectors as well as updation in technology. Irrigation Design and Research Board with its functional areas as Design, Dam Safety, Hydrology, Investigation etc., plays a prominent role in the management of Water Resources in the State. The development of reliable and efficient Flood Forecasting and Early Warning System integrated with Reservoir Operations, access to real time hydro-meteorological and reservoir data and its processing, etc. -

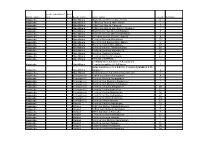

District Name Booth Correction, If Any Boot H No Booth Name

booth correction, if boot district_name any h_no booth_name office_name count Remarks Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Transmission Division,Mavelikkara 5 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara 110kV Sub Station, Mavelikkara 5 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara 220kV Sub Station, Edappon 7 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara 220kV Sub Station Sub Division, Edappon 1 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Transmission Sub Division,Edappon 2 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Transmission Sub Division Mavelikara 1 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Line Maintenance Section,Edappon 4 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Division Mavelikkara 15 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Sub Division Mavelikkara 2 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Section Mavelikkara 37 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Section Thattarambalam 32 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Section Charummood 28 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Section Kattanam 31 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Electrical Section Nooranadu 33 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara PET S/D, EDAPPON 1 Communication Sub Division K S E B S/S Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara ComplexAyranikkudi P O Edapon 2 Relay Sub Division K S E B S/S Complex Ayranikkudi P O - Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Edappon 2 Alappuzha 1 Mavelikkara Communication Sub Section Kayamkulam 1 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor 110KV Sub Station Chengannur 4 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor Electrical Division Chengannoor 15 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor Electrical Sub Division Chengannoor 1 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor Electrical Sub Division Kollakadavu 1 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor Electrical Section Chengannoor 30 Alappuzha 2 Chengannoor Electrical Section Kallisserry 25 Alappuzha -

List of Dams and Reservoirs in India 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs in India

List of dams and reservoirs in India 1 List of dams and reservoirs in India This page shows the state-wise list of dams and reservoirs in India.[1] It also includes lakes. Nearly 3200 major / medium dams and barrages are constructed in India by the year 2012.[2] This list is incomplete. Andaman and Nicobar • Dhanikhari • Kalpong Andhra Pradesh • Dowleswaram Barrage on the Godavari River in the East Godavari district Map of the major rivers, lakes and reservoirs in • Penna Reservoir on the Penna River in Nellore Dist India • Joorala Reservoir on the Krishna River in Mahbubnagar district[3] • Nagarjuna Sagar Dam on the Krishna River in the Nalgonda and Guntur district • Osman Sagar Reservoir on the Musi River in Hyderabad • Nizam Sagar Reservoir on the Manjira River in the Nizamabad district • Prakasham Barrage on the Krishna River • Sriram Sagar Reservoir on the Godavari River between Adilabad and Nizamabad districts • Srisailam Dam on the Krishna River in Kurnool district • Rajolibanda Dam • Telugu Ganga • Polavaram Project on Godavari River • Koil Sagar, a Dam in Mahbubnagar district on Godavari river • Lower Manair Reservoir on the canal of Sriram Sagar Project (SRSP) in Karimnagar district • Himayath Sagar, reservoir in Hyderabad • Dindi Reservoir • Somasila in Mahbubnagar district • Kandaleru Dam • Gandipalem Reservoir • Tatipudi Reservoir • Icchampally Project on the river Godavari and an inter state project Andhra pradesh, Maharastra, Chattisghad • Pulichintala on the river Krishna in Nalgonda district • Ellammpalli • Singur Dam -

Beth Haran Serviced Villa

+91-9961820934 Beth Haran Serviced Villa https://www.indiamart.com/bethharan-serviced-villa/ Beth Haran is a serviced villa in Wayanad District, the enchanting hill station of North Kerala. Beth Haran is a serviced villa in Wayanad District, the enchanting hill station of North Kerala. Beth Haran is in a village called ... About Us Beth Haran is a serviced villa in Wayanad District, the enchanting hill station of North Kerala. Beth Haran is a serviced villa in Wayanad District, the enchanting hill station of North Kerala. Beth Haran is in a village called Ambalavayal, the home town of historic Edakkal Caves surrounded by many ridges and malas (Rocky hills). Beth Haran captures the beauty and serenity of Cheengeri mala and Manjappara. It offers a place for peaceful and comfortable stay, an ideal base for exploring the wild, enticing and wooing nature of wayanad. Easily accessible from NH 212 (Kozhikode – Mysore), which passes through Kalpetta the District capital and S.Bathery one of the oldest town of Wayanad (Ambalavayal is at equal distance from each town) and Kozhikode – Ooty State Highway. Beth Haran is only 850 mts from Ambalavayal town en route to Karapuzha Dam. Beth Haran has 4 spacious rooms choicefully adorned with modern amenities. Villa is serviced by the owner who stays in the same compound. We are focused on providing high quality service and customer satisfaction. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/bethharan-serviced-villa/aboutus.html OTHER SERVICES P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Dinning Table AC Room Accommodation Service For Luxury Room Tourist P r o OTHER SERVICES: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Home Stay Single Bed Room Service AC Room Service Bathroom F a c t s h e e t Nature of Business :Service Provider CONTACT US Beth Haran Serviced Villa Contact Person: Lovely John Kadam Kulam,Ambalavayal Wayanad - 673593, Kerala, India +91-9961820934 https://www.indiamart.com/bethharan-serviced-villa/. -

Central Water Commission Hydrological Studies Organisation Hydrology (S) Directorate

Government of India Central Water Commission Hydrological Studies Organisation Hydrology (S) Directorate STUDY REPORT KERALA FLOODS OF AUGUST 2018 September, 2018 Contents Page No. 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Earlier floods in Kerala 2 2.0 District wise rainfall realised during 1st June 2018 to 22nd August 3 2018 3.0 Analysis of rainfall data 3 3.1 Analysis of rainfall records of 15th to 17th August 2018 5 3.2 Reservoirs in Kerala 6 4.0 Volume of runoff generated during 15th to 17th August 2018 rainfall 7 4.1 Runoff computations of Periyar sub-basin 7 4.1.1 Reservoir operation of Idukki 10 4.1.2 Reservoir operation of Idamalayar 12 4.2 Runoff computations for Pamba sub-basin 13 4.2.1 Reservoir operation of Kakki 16 4.2.2 Combined runoff of Pamba, Manimala, Meenachil and Achenkovil 18 rivers 4.3 Runoff computations for Chalakudy sub-basin 21 4.4 Runoff computations for Bharathapuzha sub-basin 25 4.5 Runoff computations for Kabini sub-basin 28 5.0 Rainfall depths realised for entire Kerala during 15-17, August 2018 31 and estimated runoff 6.0 Findings of CWC Study 32 7.0 Recommendations 35 8.0 Limitations 36 Annex-I: Water level plots of CWC G&D sites 37-39 Annex-II: Rasters of 15-17 August 2018 rainfall 40-43 Annex-III: Isohyets of Devikulam storm of 1924 44-46 Central Water Commission Hydrology (S) Dte Kerala Flood of August 2018 1.0 Introduction Kerala State has an average annual precipitation of about 3000 mm. -

Kerala Wi-Fi, Digital Life to All a Digital Kerala Initiative by Government of Kerala

Kerala Wi-Fi, Digital Life To All A Digital Kerala Initiative by Government of Kerala SL NO DISTRICT KERALA WI-FI LOCATIONS 1 Trivandrum Amboori Panchayath Office 2 Trivandrum Anad Panchayath Office 3 Trivandrum Andoorkonam Panchayath Office 4 Trivandrum Aruvikkara Grama Panchayat Office 5 Trivandrum Aryanadu Bus Stand 6 Trivandrum Aryancode Panchayat 7 Trivandrum Athiyanoor block panchayath office 8 Trivandrum Attingal Bus Stand 9 Trivandrum Attingal municipality 10 Trivandrum Attingal Munsif court 11 Trivandrum Ayurveda College 12 Trivandrum Ayurveda Marma Hospital- Kanjiramkulam 13 Trivandrum Azhoor Grama Panchayat 14 Trivandrum Chemmaruthy Grama Panchayat 15 Trivandrum Chenkal Grama Panchayat 16 Trivandrum Chirayinkeezh Grama Panchayat 17 Trivandrum Chirayinkeezhu Block Panchayath office 18 Trivandrum Chirayinkeezhu Taluk Hospital 19 Trivandrum Chirayinkeezhu Taluk Office 20 Trivandrum Civil Station 1 21 Trivandrum Commissioner office thycaud 22 Trivandrum District Model Hospital, Peroorkada 23 Trivandrum East Fort Bus stand 24 Trivandrum Fort Hospital 25 Trivandrum General Hospital Thiruvananthapuram 26 Trivandrum Govt. Homeopathic Medical college Hospital Iranimuttom 27 Trivandrum Kadakkavoor Grama Panchayat 28 Trivandrum Kadinamkulam Panchayath Office 29 Trivandrum Kallara Grama Panchayath Office 30 Trivandrum Kallikkad Grama Panchayat 31 Trivandrum Kalliyoor Grama Panchayat 32 Trivandrum Kanakakunnu Palace 33 Trivandrum Kaniyapuram Bus Stand 34 Trivandrum Karakulam Grama Panchayat 35 Trivandrum Karode Grama Panchayat office 36 -

List of Hotels for Paid Quarantine for NRK's

List of Hotels for paid quarantine for NRK's Single Double Sl Hotel Name Full Address with Taluk Category Phone no: (mob & land) & email id Room charges(Rs) Room charges(Rs) Number of rooms Number of rooms Total No. (incl gst) (incl gst) Remarks Rooms A/c Non A/c A/c Non A/c A/c Non A/c A/c Non A/c Poomala PO, Manichira, 04936 -221900, 9400008664 1 KTDC Pepper Grove. S. Bathery Hotel 2000/2500 2400/2900 11 Incl food Sultan Bathery, Kerala 673592 [email protected] Karapuzha Dam, 2 Vistara Resort , Sulthan Bathery Kalathuvayal, Ambalavayal, Resort 9072111299 [email protected] 2000 3000 15 Food charges extra Kerala 673593 Vythiri -Tharuvana Rd, 3 Seagot Banasura Resorts, Kalpetta Resort 9747440404 [email protected] 2000 2500 6 Food charges extra Padinjarathara, Kerala 673575 1500 2000 34 Food charges extra T.B. Road, Kalpetta, 8281 554 015 , 4 Green Gates Hotel , Kalpetta Hotel Wayanad, Kerala 673122 [email protected] 2500 5000 Food charges extra Abad Brookside Lakkidi, Wayanad Lakkidi , Wayanad Kerala 5 Resorts 9746411601, [email protected] 4000 4000 30 Food charges extra 673576 Contour Island Resort and Spa , Kuttiyamvayal Varambetta 9562056777 6 Resort 6000 7000 22 Food charges extra Wayanad, Kerala PO, Kerala 673575 [email protected] near Edakkal Caves, 7 Edakkal Hermitage Resorts Resorts 9847001491 [email protected] 2000 15 Food charges extra Ambalavayal, Kerala 673592 WAYANAD SILVER WOODS- Manjoora P.O, Vythiri - 8 Resort 9447666011 [email protected] 4000 5000 21 Food charges extra Vythiri Tharuvana Rd, Kerala 673575 0th Mile ,Thariode PO, Vythiri 9 Petals Resorts, Vythiri -Tharuvana Rd, near St.Jude Resort 8111862888 [email protected] 2000 16 Food charges extra Church, Kerala 673575 Annapoorna Estate, Survey No. -

Tackling a Deluge. Wayanad 2020

Tackling a deluge. Wayanad 2020 The report illustrates how District Administration and DDMA , Wayanad studied, analyzed the disasters and designed solutions to save lives un- der the leadership of Dr. Adeela Abdulla I A S, Chairperson of DDMA. Page 1 of 13 REPORT ON ACTIVITIES BY DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION & DDMA in 2019 and 2020 Table of Contents Sl no Content Page no 1 Abstract 3 2 Wayanad at a glance 4 3 Brief Disaster Profile 5 4 General aspect of the District 6 5 Initiatives at a glance 7 6 Dam Management 8 7 Rain gauge data collection 9 8 Debris removal 11 9 Sustainability 12 10 Conclusion 13 DEOC WAYANAD 2021 2 REPORT ON ACTIVITIES BY DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION & DDMA in 2019 and 2020 Abstract: The disasters are not a new phenomenon for Wayanad anymore. The deluge, landslide, land subsidence or any other monsoon related mayhem is usual in Wayanad during the South West monsoon which usually commence from the first week of June. The heavy rainfall makes the situation tougher and danger- ous in most of the parts of the District. The DDMA has been taking up various Disaster mitigation measures to safeguard the General Public from any even- tuality after close observation of past incidents. The learning and assessment from the past disasters helped the Administration to take proactive measures to reduce the impact of the natural disaster. This report is an attempt to bring all the novel initiatives before the public. In the ensuing years this will help the District Administration to replicate the activities in the eve of disasters and catastrophes of various natures. -

Download E Brochure (Cloudscape)

Get a bird’s eye view of naTURE THEY SAY, REACH FOR THE STARS. HERE, YOU LITERALLY DO. Tucked away at an altitude of 2296 feet above sea level, the air is fresh and crisp. It’s where you come face to face with the milky way. Waynad Pass : Commisioned by NATH construction on 2014) MAKE YOURSELF AT HOME. Immerse yourself in nature’s offerings, at one of the highest locations and the only ‘Gateway of Wayanad’-Lakkidi. Perched on the high mist-clad mountains where the gurging streams and springs, fresh green vegetation and the dense forests lay, it is here, where a real lifestyle originates. Where luxury is seen in the glory of nature. BE ON TOP OF THE VANTAGE POINT. Lakkidi. A true rainforest destination. Popularly known as the “chirapunjee of Kerala”. With an average rainfall ranging from 6000–6500 mm or above, makes Lakkidi the second highest location receiving maximum rainfall in the world, as well as one of coldest in Kerala. Cloudscape cloud·scape (kloud′skāp′) n. A WORK OF ART REPRESENTING A 1. A work of art representing a view of clouds: an Impressionist painting that is a vast cloudscape of buoyant, floating forms. 2. A photograph showing a view of clouds, such as those surrounding a planet. VIEW OF CLOUDS American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2011 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. cloudscape (′kla′dske′p) n 1. (Physical Geography) a picturesque formation of clouds 2. a picture or photograph of such a formation With the most mesmerizing aspect of Lakkidi, the mist, the entire project is precisely placed here inorder to let you experience the reality of the location and lifestyle. -

Karapuzha Irrigation Project

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FINAL REPORT KARAPUZHA IRRIGATION PROJECT LAND ACQUISITION Muppainadu, Ambalavayal and Thomattuchal Villages of Wayanad District Don Bosco Arts & Science College Angadikadavu, Iritty, Kannur – 670 706 Phone: (0490) 2426014; Mob: 9961200787 Email: [email protected] SIA Unit 9495903108 August 2019 i CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 01 1.2 Project Location and Alternatives considered 02 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 02 1.4 Searches for Alternative Route 03 1.5 Social Impact 03 1.6 Inventory Details of the Affected Property 04 1.7 Social Impact Mitigation Plan (SIMP) 10 1.8 Mitigation Measures 11 1.9 Suggestions by the affected for Mitigating the Impacts 12 CHAPTER 2 - DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background and Rationale of the Project 14 2.2. Project Size & Location 14 2.3. Examination of Alternatives 14 2.4 The Project Construction Progress 15 2.5 Details of Environment Impact Assessment 15 2.6 Workforce Requirement 15 2.7 Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 15 2.8 Applicable Rules and Statutes 15 CHAPTER 3 – TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH, METHODOLOGY AND SCHEDULE 3.1 Background 17 3.2 SIA Team 17 3.3 SIA and SIMP Preparation Process 18 3.4 Methodology and Data Collection 19 3.5 Site Visits and Information Gathering 20 3.6 Schedule of Activities 21 3.7 List of Key Informants Contacted & Interacted 22 3.8 Summary of Public Hearing 22 CHAPTER 4 - VALUATION OF LAND 4.1 Background 28 4.2 Village-wise Land Detail 28 4.3 Type of Land Affected 28 -

Q" Ocsccncolceioa Ggorffdlc{O C!A,G Oqpjl) @1

oto'lcDcerco oe(oe (r)'lqDocruG GIO5IOI Co flUO4IDPOo 11. 05. 2017- oa 0qolsl6)" {r)resa@) a11orDol1! GolcGJo cn.. i 5 2 (o o ojl o cnc ocnr srq c @ oo ol elsD'lo el oros'lcruom cruc e ojlacnrcn GolSGJo PCOrOoo mJcco(goa q,,oi. c. <aroJd. coq E)il. a,sa,..'rgg| (@il oil. cucot ( m"l.na,o amqo ojlcmc omlerol coq" ocsccncolceioA GGorffDlc{o c!a,g oqpjl) @1. "0t.. pc crudmcd rarourlocoorojloE ocrnG(ooeo .,0) g-r2c crud,otcd crouJlacoonrjloE "0) GroslcrDocm o JcmGco(r9lo oilccnc cm-)erol co oilccncccruelolco eoelpltoiloel 161..Jo-DojlauEal" coelocoiloor rsadlcruncm olJlcooJ crilom:cnorollmcojl maflailoilgene". (dcrB(o) r:r u'rrlloJ oilomrmoroilcnc(oil reo6mc(ooojl "l'rDctil Grdco6Dff\Do '"0' rorqdl eoorrccroolo'i moEailcol olc])ctil6ua 6gos oilcloesBuA ()dl orDc oe)(a) 3o5m cnd. po cojlr6E G-"rd(omilol6rcrro. pcrLcoiloE crgco.Gl4 60 aralro oqos olcrco cro(oorBl 4 .lr?r)ojlouA o{lo(o)som 6ru cnD enil' icrg coi c dd tirrdt @1 6 crro. aOSO6fDffoo ct{61ot oS6lGOc; 6sBUa Gocro "' o8 .Jr2l)(di6ua orgo.releccmoilcri cc1]6rclqg g (C3ooe ms.Jslloud oilojlo "el5oroilelc em" 6riill (clolo) orc])ojl6crE corlo c mrocolo ,1d oroilcorca::crnojlcn cojl 6T'il) rl^) sors'l6uA ffull6col eil 3c61te3: q. ms.'-rs1 m;llao1 4 crto:crro. r.l .-,tl gr)(oil6)(t Gs(')o JCol djccoc m)l) .rrc!(otocolqo ocii4e€ q" tt;roorcorcscn cco3trl5gBUa (a)ro3Clu0l(oJo colo:cmoilcoo ppoccoll 6ucrrl>oes Qre.daCos @ord(orom" aco5asaoocol jl co. ms;s1 "6coc -jleocmojl .rull6col6rcoc? }.rye offua,sara cc"rilmld IWA\ a,v o"vtravb ao,filrlm.orcIob "*'fu-t'b' "g'"'*"d udZ LTSTOF sANcrroNED FoR Tr{E FINANCIAi w4,n zorcrz c zorz-ra SI AS Amount No.