COUNTRYSIDE for ALL? the IMPLICATIONS for PLANNING and RESEARCH 1 Panel Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CCW Over Its 22 Year Existence

As the Countryside Council for Wales was completing its 2012-2013 programme of work towards targets agreed with Welsh Government, Chair, Members of Council and Directors felt that it would be appropriate to record key aspects of the work of CCW over its 22 year existence. This book is our way of preserving that record in a form that can be retained by staff and Council Members past and present. CCW has had to ‘learn while doing’, and in many instances what we understand today is the fruit of innovation over the past two decades. Little of the work of CCW has been done alone. Many of the achievements in which we take pride were made in the face of formidable difficulties. Rising to these challenges has been possible only because of the support, advice and active involvement of others who share our passion for the natural environment of Wales. They, like we, know that our ecosystems, and the goods and services that stem from their careful stewardship, are our most valuable asset: our life support system. Together with our many partners in non-governmental organisations, from local community groups of volunteers through to national and international conservation bodies as well as central and local government, we have endeavoured to conserve and protect the natural resources of Wales. We are therefore offering copies of this book to our partners as a tribute to their involvement in our work – a small token of our gratitude for their friendship, support and wise counsel. There is still a great deal to learn, and as we now pass the baton to the new single environment body, Natural Resources Wales, we recognise that the relationships with partners that have been invaluable to the Countryside Council for Wales will be equally crucial to our successor. -

Route Master

magazine autumn 2012 magazine autumn 2012 Wales Wales Aberhosan, Powys Trawsfynydd, Gwynedd 09/08/2012 17:20 Route 05 Route 06 master G Distance 10½km/6½ miles G Time 3½hrs G Type Hill master G Distance 18km/11 miles G Time 7hrs G Type Mountain NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL Plan your walk Plan your walk G Snowdonia Chester G GWYNEDD POWYS TRAWSFYNYDD ABERHOSAN G Shrewsbury G G Newtown Rhayader G Aberystwyth G Lampeter G G Llandrindod Wells Brecon WHERE: Circular walk WHERE: Circular walk from Aberhosan via the from Trawsfynydd, in Vaughan-Thomas memorial central Snowdonia’s PHOTOGRAPHY: NEIL COATES PHOTOGRAPHY: viewpoint and Glaslyn. FIONA BARLTROP PHOTOGRAPHY: Rhinogydd mountains. START/END: Aberhosan The village of Aberhosan is The spot was a favourite START/END: Trawsfynydd This is Snowdonia at its most handgate and up a walled track village bus stop (SN810974). situated a few miles south-east viewpoint of his. village car park (SH707356). remote, with few people and past a stone barn to a stile. Drift TERRAIN: Stony and grassy of Machynlleth, off the scenic TERRAIN: Lanes, rough even fewer paths. But the rewards R, roughly parallel to the wall, upland tracks, mountain paths and pathless mountain mountain road that goes via 1. START From the bus stop for your perseverance are an to a higher stile. Climb over and road and country lanes with terrain, which can be the old mining settlement at at the top of Aberhosan incredible Bronze Age monument, aim ahead-L to walk up beside some pathless stretches. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Beck Farm, Rocks Lane Burniston YO13 0HX an Exceptional Stone Built Farmhouse in the Outskirts of Burniston

Burniston YO13 0HX YO13 Burniston Beck Farm, Rocks Lane Rocks Farm, Beck You may download, store and use the material for your own personal use and research. You may not republish, retransmit, redistribute or otherwise make the material available to any party or make the same available on any website, online service or bulletin board of your own or of any other party or make the same available in hard copy or in any other media without the website owner's express prior written consent. The website owner's copyright must remain on all reproductions of material taken from this website. An exceptional stone built farmhouse in the outskirts of Burniston • Exceptional Stone Farmhouse • Three Double Bedrooms • Character Features • Beautiful Rural Position 25 Northway, Scarborough, • Gas Central Heating North Yorkshire, YO11 1JH • Available Now 01723 341557 • Unfurnished [email protected] • Council Tax Band E £1,100 Per calendar month www.harris-shieldscollection.uk Description Beck Farmhouse is a stunning and spacious stone built home retaining many character features yet boasting a contemporary interior. Part of the Duchy Of Lancaster's Cloughton Estate, it is set within a semi rural and tranquil position within the sought-after village of Burniston. The property benefits from gas central heating and part double glazing. The accommodation briefly comprises; entrance hall with under-stairs cupboard, large fitted kitchen/dining room with integrated washing machine and dish-washer, separate utility room leading to a WC. Formal dining area and sitting room with log burner. On the first floor are three generously sized double bedrooms and a large bathroom with white three piece suite and separate shower. -

NLCA06 Snowdonia - Page 1 of 12

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA06 Snowdonia Eryri – Disgrifiad cryno Dyma fro eang, wledig, uchel, sy’n cyd-ffinio’n fras â Pharc Cenedlaethol Eryri. Ei nodwedd bennaf yw ei mynyddoedd, o ba rai yr Wyddfa yw mynydd uchaf Cymru a Lloegr, yn 3560’ (1085m) o uchder. Mae’r mynyddoedd eraill yn cynnwys y Carneddau a’r Glyderau yn y gogledd, a’r Rhinogydd a Chadair Idris yn y de. Yma ceir llawer o fryndir mwyaf trawiadol y wlad, gan gynnwys pob un o gopaon Cymru sy’n uwch na 3,000 o droedfeddi. Mae llawer o nodweddion rhewlifol, gan gynnwys cribau llymion, cymoedd, clogwyni, llynnoedd (gan gynnwys Llyn Tegid, llyn mwyaf Cymru), corsydd, afonydd a rhaeadrau. Mae natur serth y tir yn gwneud teithio’n anodd, a chyfyngir mwyafrif y prif ffyrdd i waelodion dyffrynnoedd a thros fylchau uchel. Yn ddaearegol, mae’n ardal amrywiol, a fu â rhan bwysig yn natblygiad cynnar gwyddor daeareg. Denodd sylw rhai o sylfaenwyr yr wyddor, gan gynnwys Charles Darwin, a archwiliodd yr ardal ym 1831. Y mae ymhell, fodd bynnag, o fod yn ddim ond anialdir uchel. Am ganrifoedd, bu’r ardal yn arwydd ysbryd a rhyddid y wlad a’i phobl. Sefydlwyd bwrdeistrefi Dolgellau a’r Bala yng nghyfnod annibyniaeth Cymru cyn y goresgyniad Eingl-normanaidd. Felly, hefyd, llawer o aneddiadau llai ond hynafol fel Dinas Mawddwy. O’i ganolfan yn y Bala, dechreuodd y diwygiad Methodistaidd ar waith trawsffurfio Cymru a’r ffordd Gymreig o fyw yn y 18fed ganrif a’r 19eg. Y Gymraeg yw iaith mwyafrif y trigolion heddiw. -

Protected Landscapes: the United Kingdom Experience

.,•* \?/>i The United Kingdom Expenence Department of the COUNTRYSIDE COMMISSION COMMISSION ENVIRONMENT FOR SCOTLAND NofChern ireianc •'; <- *. '•ri U M.r. , '^M :a'- ;i^'vV r*^- ^=^l\i \6-^S PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from UNEP-WCIVIC, Cambridge http://www.archive.org/details/protectedlandsca87poor PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Prepared by Duncan and Judy Poore for the Countryside Commission Countryside Commission for Scotland Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Published for the International Symposium on Protected Landscapes Lake District, United Kingdom 5-10 October 1987 * Published in 1987 as a contribution to ^^ \ the European Year of the Environment * W^O * and the Council of Europe's Campaign for the Countryside by Countryside Commission, Countryside Commission for Scotland, Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources © 1987 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Avenue du Mont-Blanc, CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Additional copies available from: Countryside Commission Publications Despatch Department 19/23 Albert Road Manchester M19 2EQ, UK Price: £6.50 This publication is a companion volume to Protected Landscapes: Experience around the World to be published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, -

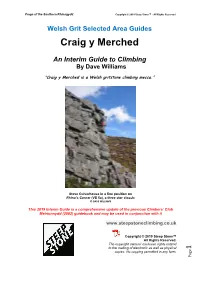

Craig Y Merched

Crags of the Southern Rhinogydd Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ - All Rights Reserved Welsh Grit Selected Area Guides Craig y Merched An Interim Guide to Climbing By Dave Williams “Craig y Merched is a Welsh gritstone climbing mecca.” “Imbued with a delightful sense of isolation, this is a wonderful place to get away from it all” Steve Culverhouse in a fine position on Rhino’s Corner (VS 5a), a three star classic © DAVE WILLIAMS This 2019 Interim Guide is a comprehensive update of the previous Climbers’ Club Meirionnydd (2002) guidebook and may be used in conjunction with it www.steepstoneclimbing.co.uk Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ All Rights Reserved. The copyright owners’ exclusive rights extend to the making of electronic as well as physical 1 copies. No copying permitted in any form. Page Crags of the Southern Rhinogydd Copyright © 2019 Steep Stone™ - All Rights Reserved The Rhinogydd The Rhinogydd are a range of mountains located in Central Snowdonia, south of the Afon Dwyryd, east of Harlech, west of the A470 and north of the Afon Mawddach. Rhinogydd is the Welsh plural form of Rhinog, which means ‘threshold’. It is thought that the use of Rhinogydd derives from the names of two of the higher peaks in the range, namely Rhinog Fawr and Rhinog Fach. The Rhinogydd are notably rocky towards the central and northern end of the range, especially around Rhinog Fawr, Rhinog Fach and Moel Ysgyfarnogod. This area is littered with boulders, outcrops and large cliffs, all composed of perfect gritstone. The southern end of the range around Y Llethr and Diffwys has a softer, more rounded character, but this does not mean that there is an absence of climbable rock. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Temple Hill Wind Farm

TEMPLE HILL WIND FARM ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT VOLUME 1: MAIN TEXT Produced by Stephenson Halliday September 2013 VOLUME 1: MAIN TEXT Contents 1 Introduction 2 Approach to the Environmental Impact Assessment 3 Site Selection and Design 4 Project Description 5 Planning Policy 6 Landscape and Visual 7 Ecology 8 Ornithology 9 Noise 10 Historic Environment 11 Ground Conditions 12 Hydrology and Hydrogeology 13 Access, Traffic and Transportation 14 Aviation 15 Telecommunications and Television 16 Socio-Economic Effects 17 Shadow Flicker 18 Summary of Predicted Effects and Conclusions RWE Npower Renewables Ltd Temple Hill Wind Farm Environmental Statement 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1.1.1 This Environmental Statement (ES) has been prepared by Stephenson Halliday (SH) on behalf of RWE Npower Renewables Ltd (RWE NRL) to accompany an application for planning permission submitted to South Kesteven District Council (SKDC). 1.1.2 The application seeks consent under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 for the erection of 5 wind turbines up to 126.5m to blade tip and construction of associated infrastructure on land at Temple Hill, between Grantham and Newark-on-Trent (‘the Development’). Further detail on the Development is provided in Chapter 4: Project Description. 1.1.3 The ES assesses the likely significant effects of the Development in accordance with the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2011. 1.1.4 The site is located in the South Kesteven administrative area approximately 7km south east of Newark-on-Trent and 9km north of Grantham (unless otherwise stated, distances are measured from the closest turbine as the primary element of the Development and assessment). -

Hill Walking & Mountaineering

Hill Walking & Mountaineering in Snowdonia Introduction The craggy heights of Snowdonia are justly regarded as the finest mountain range south of the Scottish Highlands. There is a different appeal to Snowdonia than, within the picturesque hills of, say, Cumbria, where cosy woodland seems to nestle in every valley and each hillside seems neatly manicured. Snowdonia’s hillsides are often rock strewn with deep rugged cwms biting into the flank of virtually every mountainside, sometimes converging from two directions to form soaring ridges which lead to lofty peaks. The proximity of the sea ensures that a fine day affords wonderful views, equally divided between the ever- changing seas and the serried ranks of mountains fading away into the distance. Eryri is the correct Welsh version of the area the English call Snowdonia; Yr Wyddfa is similarly the correct name for the summit of Snowdon, although Snowdon is often used to demarcate the whole massif around the summit. The mountains of Snowdonia stretch nearly fifty miles from the northern heights of the Carneddau, looming darkly over Conwy Bay, to the southern fringes of the Cadair Idris massif, overlooking the tranquil estuary of the Afon Dyfi and Cardigan Bay. From the western end of the Nantlle Ridge to the eastern borders of the Aran range is around twenty- five miles. Within this area lie nine distinct mountain groups containing a wealth of mountain walking possibilities, while just outside the National Park, the Rivals sit astride the Lleyn Peninsula and the Berwyns roll upwards to the east of Bala. The traditional bases of Llanberis, Bethesda, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed and Beddgelert serve the northern hills and in the south Barmouth, Dinas Mawddwy, Dolgellau, Tywyn, Machynlleth and Bala provide good locations for accessing the mountains. -

Lighting Plan

Exterior Lighting Master Plan Ver.05 -2015 Snowdonia National Park – Dark Sky Reserve External Lighting Master Plan Contents 1 Preamble 1.1.1 Introduction to Lighting Master Plans 1.1.2 Summary of Plan Policy Statements 1.2 Introduction to Snowdonia National Park 1.3 The Astronomers’ Point of View 1.4 Night Sky Quality Survey 1.5 Technical Lighting Data 1.6 Fully Shielded Concept Visualisation 2 Dark Sky Boundaries and Light Limitation Policy 2.1 Dark Sky Reserve - Core Zone Formation 2.2 Dark Sky Reserve - Core Zone Detail 2.3 Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E0's 2.4 Energy Saving Switching Regime (Time Limited) 2.5 Dark Sky Reserve – Buffer Zone 2.5.1 Critical Buffer Zone 2.5.2 Remainder of Buffer Zone 2.6 Light Limitation Plan - Environmental Zone E1's 2.7 Environmental Zone Roadmap in Core and Critical Buffer Zones 2.8 External Zone – General 2.9 External Zone – Immediate Surrounds 3 Design and Planning Requirements 3.1 General 3.2 Design Stage 3.2.1 Typical Task Illuminance 3.2.2 Roadmap for Traffic and Residential Area lighting 3.3 Sports Lighting 3.4 Non-photometric Recipe method for domestic exterior lighting 4 Special Lighting Application Considerations 5 Existing Lighting 5.1 Lighting Audit – General 5.2 Recommended Changes 5.3 Sectional Compliance Summary 5.4 Public Lighting Audit 5.5 Luminaire Profiles 5.6 Public Lighting Inventory - Detail Synopsis Lighting Consultancy And Design Services Ltd Page - 1 - Rosemount House, Well Road, Moffat, DG10 9BT Tel: 01683 220 299 Exterior Lighting Master Plan Ver.05 -2015 APPENDICES -

Site Assessments

SHELAA Site Assessments Scarborough Borough Council February 2015 1 Contents Final SHELAA Calculations by Area 3 Site Assessments by Area 4 - Reighton and Speeton 4 - Hunmanby 11 - Filey 17 - Folkton / Flixton 24 - Muston 25 - Gristhorpe 26 - Lebberston 27 - Cayton 28 - Scarborough 37 - Newby and Scalby 45 - Osgodby 50 - Eastfield 51 - Seamer 54 - Irton 61 - East / West Ayton 62 - Wykeham / Ruston 65 - Snainton 68 - Burniston 72 - Cloughton 76 - Whitby 81 - Eskdaleside 88 Sites Post 2030 90 Sites taken out of SHELAA for 2014 Update 124 Maps of Sites by Area - Reighton and Speeton - Hunmanby - Filey and Muston - Folkton and Flixton - Gristhorpe - Eastfield, Cayton and Lebberston - Scarborough (Map 1) - Scarborough (Map 2) - Newby and Scalby - Seamer, Irton, East and West Ayton - Wykeham, Brompton, Ruston and Snainton - Cloughton and Burniston - Whitby and Sleights *Please note that the references in this document are different to those in subsequent LDP/Local Plan documents as sites have been combined to reduce the overall number of assessments. The site references which correspond to the LDF/Local Plan have been included for clarity and cross reference purposes 2 Final SHELAA Calculations by Settlement Area Housing Land1 Employment Land2 0-5 Years 6-10 Years 11 - 16 Years Beyond 2030 0-17 Years Beyond 2030 Reighton 0 0 592 0 - - Hunmanby 0 182 275 184 24,500 - Filey 52 53 490 0 - - Folkton / Flixton 0 0 10 150 - - Muston 12 0 0 48 - - Gristhorpe 45 0 0 0 - - Lebberston 0 0 26 0 - - Cayton 95 1533 1835 503 80,500 - Osgodby 58 0 0 0 - -