Anthropology, Race and Evolution: Rethinking the Legacy of Wilhelm Bleek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Développement De La Linguistique Bantu

Développement de la PREAMBULE Plan linguistique bantu Figures, approches, repr ésentations G. Philippson , L. van der Veen Séminaire linguistique bantu 2 Introduction Sources, premières références Emergence et développements INTRODUCTION Premiers travaux Sources, premières références De 1860 à 1940 De 1940 à nos jours Classification Représentations Conclusion Bibliographie Séminaire linguistique bantu 3 Séminaire linguistique bantu 4 1 Introduction Introduction • Sélection de publications sur l’histoire de la linguistique bantu : • Premières références – Doke & Cole (1961) – L’hiéroglyphe égyptien punt ?? (2500 av. J.-C.) – Bastin (1978), Guarisma (1978), Leroy & Voorhoeve (1978) • Anachronisme… – Vansina (1979, 1980) – Sources arabes à partir de 902 : attestations de mots recueillis le – Flight (1980, 1988) long du littoral oriental – Alexandre (1959, 1968) – Andrea Corsali , navigateur italien (1487-?) : « même langue – Chrétien (1985) parlée du Cap de Bonne Espérance jusqu’à la mer Rouge » – Williamson & Blench (2000) – Ecrits portugais à partir du 16 ème siècle : toponymes, anthro- – Blench (2006) ponymes (côtes ouest et, surtout, est) Séminaire linguistique bantu 5 Séminaire linguistique bantu 6 Introduction – Ecrit du mathématicien italien Antonio Pigafetta (à partir de données rapportées par Lopez en 1588) : un grand nombre de EMERGENCE ET DEVELOPPEMENTS mots de la côte ouest (langue : kongo) Figures, approches – Ouvrages des Anglais Battel (début 17 ème ) et Herbert (1677) Intérêt historique réel, mais pas de véritables études -

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY of REGULATION of REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES an Experimental Approach Using a Multi-Agent Based Simulation System

SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES An experimental approach using a multi-agent based simulation system Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät I Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg und Facultat de Lletres i Filosofia Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona von Frau Juana Maria Olives Pons geb. am 04.04.1991 in Maó Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Assumpció Vila Mitja Prof. Dr. Raquel Piqué Huerta Dr. Pablo Cayetano Noriega Blanco Vigil Dr. Jordi Sabater Mir Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Datum der Verteidigung: 18.10.2019 Doctoral thesis __________________ Departament de Prehistòria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Prähistorische Archäologie und Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit von Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg SOCIAL NORMS AS STRATEGY OF REGULATION OF REPRODUCTION AMONG HUNTING-FISHING-GATHERING SOCIETIES AN EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH USING A MULTI-AGENT BASED SIMULATION SYSTEM Juana Maria Olives Pons Prof. Dr. François Bertemes Prof. Dr. Jordi Estévez Escalera 2019 Table of Contents Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................................. i Resum .............................................................................................................................................. xi Summary ....................................................................................................................................... -

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER and PRECURSOR of ROCK ART CONSERVATION Today George William Stow Is Remembered Chiefly As

CHAPTER 1 GEORGE WILLIAM STOW, PIONEER AND PRECURSOR OF ROCK ART CONSERVATION One thing is certain, if I am spared I shall use every effort to secure all the paintings in the state that I possibly can, that some record may be kept (imperfect as it must necessarily be .... ). I have never lost an opportunity during that time of rescuing from total obliteration the memory of their wonderful artistic labours, at the same time buoying myself up with the hope that by so doing a foundation might be laid to a work that might ultimately prove to be of considerable importance and value to the student of the earlier races of mankind. George William Stow to Lucy Lloyd, 4 June 1877 Today George William Stow is remembered chiefly as the discoverer of the rich coal deposits that were to lead to the establishment of the flourishing town of Vereeniging in the Vaal area (Mendelsohn 1991:11; 54-55). This achievement has never been questioned. However, his considerable contribution as ethnographer, recorder of rock art and as the precursor of rock art conservation in South Africa, has never been sufficiently acknowledged. In the chapter that follows these achievements are discussed against the backdrop of his geological activities in the Vereeniging area and elsewhere. Inevitably, this chapter also includes a critical assessment of the accusations of fraud levelled against him in recent years. Stow was a gifted historian and ethnographer and during his geological explorations he developed an abiding interest in the history of the indigenous peoples of South 13 Africa and their rich rock art legacy. -

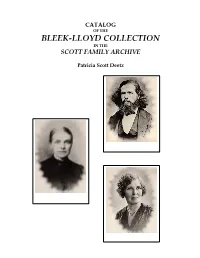

Bleek-Lloyd Collection in the Scott Family Archive

CATALOG OF THE BLEEK-LLOYD COLLECTION IN THE SCOTT FAMILY ARCHIVE Patricia Scott Deetz © 2007 Patricia Scott Deetz Published in 2007 by Deetz Ventures, Inc. 291 Shoal Creek, Williamsburg, VA 23188 United States of America Cover Illustrations Wilhelm Bleek, 1868. Lawrence & Selkirk, 111 Caledon Street, Cape Town. Catalog Item #84. Lucy Lloyd, 1880s. Alexander Bassano, London. Original from the Scott Family Archive sent on loan to the South African Library Special Collection May 21, 1993. Dorothea Bleek, ca. 1929. Navana, 518 Oxford Street, Marble Arch, London W.1. Catalog Item #200. Copies made from the originals by Gerry Walters, Photographer, Rhodes University Library, Grahamstown, Cape 1972. For my Bleek-Lloyd and Bright-Scott-Roos Family, Past & Present & /A!kunta, //Kabbo, ≠Kasin, Dia!kwain, /Han≠kass’o and the other Informants who gave Voice and Identity to their /Xam Kin, making possible the remarkable Bleek-Lloyd Family Legacy of Bushman Research About the Author Patricia (Trish) Scott Deetz, a great-granddaughter of Wilhelm and Jemima Bleek, was born at La Rochelle, Newlands on February 27, 1942. Trish has some treasured memories of Dorothea (Doris) Bleek, her great-aunt. “Aunt D’s” study was always open for Trish to come in and play quietly while Aunt D was focused on her Bushman research. The portraits and photographs of //Kabbo, /Han≠kass’o, Dia!kwain and other Bushman informants, the images of rock paintings and the South African Archaeological Society ‘s logo were as familiar to her as the family portraits. Trish Deetz moved to Williamsburg from Charlottesville, Virginia in 2001 following the death of her husband James Fanto Deetz. -

Prison and Garden

PRISON AND GARDEN CAPE TOWN, NATURAL HISTORY AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATION HEDLEY TWIDLE PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JANUARY 2010 ii …their talk, their excessive talk about how they love South Africa has consistently been directed towards the land, that is, towards what is least likely to respond to love: mountains and deserts, birds and animals and flowers. J. M. Coetzee, Jerusalem Prize Acceptance Speech, (1987). iii iv v vi Contents Abstract ix Prologue xi Introduction 1 „This remarkable promontory…‟ Chapter 1 First Lives, First Words 21 Camões, Magical Realism and the Limits of Invention Chapter 2 Writing the Company 51 From Van Riebeeck‟s Daghregister to Sleigh‟s Eilande Chapter 3 Doubling the Cape 79 J. M. Coetzee and the Fictions of Place Chapter 4 „All like and yet unlike the old country’ 113 Kipling in Cape Town, 1891-1908 Chapter 5 Pine Dark Mountain Star 137 Natural Histories and the Loneliness of the Landscape Poet Chapter 6 „The Bushmen’s Letters’ 163 The Afterlives of the Bleek and Lloyd Collection Coda 195 Not yet, not there… Images 207 Acknowledgements 239 Bibliography 241 vii viii Abstract This work considers literary treatments of the colonial encounter at the Cape of Good Hope, adopting a local focus on the Peninsula itself to explore the relationship between specific archives – the records of the Dutch East India Company, travel and natural history writing, the Bleek and Lloyd Collection – and the contemporary fictions and poetries of writers like André Brink, Breyten Breytenbach, Jeremy Cronin, Antjie Krog, Dan Sleigh, Stephen Watson, Zoë Wicomb and, in particular, J. -

An Overview Translation History South Africa 1652

An Overview of Translation History in South Africa 1652–1860 By Birgitt Olsen A research report submitted to the Faculty of the Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts: Translation Adelaide, South Australia, 2008 i Abstract This research report comprises an outline of South African translation history in the years 1652 – 1860. The report is divided into three chapters, covering scriptural and secular translation history across two time periods, namely 1652-1750 (scriptural and secular), 1750-1860 (scriptural) and 1750-1860 (secular). A catalogue of translations done in these time periods is also included. The research methodology is based on hermeneutical principles, and therefore seeks to interpret and represent historical material in a way that makes it relevant for contemporary circumstances, always focusing on the individuals involved in events as well as taking into account the subjectivity of the researcher. In conclusion, but also as a part of the overall rationale for performing the research, the report discusses the immediate importance to modern society of understanding the historical linguistic dynamics between cultures, as represented in translation activity. ii Declaration I declare that this research report is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts: Translation, in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. ________________________________ Birgitt Olsen 20th day of November, 2008 iii Acknowledgements My sincere and warm thanks go to my supervisor, Dr Elizabeth Meintjes, for her perspicacious, patient and humorous assistance in the years it to me took complete this research report. -

Communities and Rites of Passage

Cambridge University Press 0521554853 - A History of South African Literature Christopher Heywood Excerpt More information chapter 1 Introduction: communities and rites of passage south african communities: conflict and literature Amidst confusion, violence, and conflict, South African literature has arisen out of a long tradition of resistance and protest.∗ In order of their arrival, four main communities have emerged in the course of settlement over the past millennia. These are: (a) the ancient hunter-gatherer and early pastoralist Khoisan (Khoi and San∗) and their modern descendants, the Coloured community of the Cape; (b) the pastoralist and agricul- tural Nguni and Sotho (Nguni–Sotho), arriving from around the eleventh century ce; (c) the maritime, market-oriented and industrialised Anglo- Afrikaner settlers, arriving since the seventeenth century; and (d) the Indian community, arriving in conditions of servitude in the nineteenth century. All these and their sub-communities are interwoven through creolisation, the result of daily contacts varying from genocide to love-making. The result of the interweaving is a creolised society and an abundance of oral and written literatures. Super-communities have been formed by women, gays or male and female homosexuals, and religious and political groups. Distinctive literary movements have grown around all these community divisions. A literary example from the earliest community relates to the exter- mination and assimilation of the Khoisan community. Kabbo, a San (‘Bushman’∗) performer from South Africa’s most ancient community, with an oral literary tradition that goes back many thousand years, narrated his journey to imprisonment in Cape Town after his arrest for stealing sheep: We went to put our legs into the stocks; another white man laid another piece of wood upon our legs. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Background to the project This book had its origins in an extraordinary discovery in 2007 by Mike Besten,1 that two or three elderly people in and around Bloemfontein and Bloemhof still remembered fragments of the old language of the Korana people, which was referred to by its speakers as ǃOra. Until then, it had simply been assumed that the language must long ago have disappeared – and with it, the last traces of the Khoekhoe variety known to have been closest to the language spoken by the original Khoi inhabitants of Table Bay when European sailing ships began to appear around the Cape coastline towards the end of the 15th century. The historical and cultural significance of this discovery was immense. Besten, who was an historian rather than a linguist, did not lose time in calling for the help of colleagues, and some of us were privileged to accompany him on a preliminary visit to one of these speakers, Oupa Dawid Cooper, in December 2008. Even though Oupa Dawid recollected only a little of the language, it was clear that his variety had all the well-known signature features of Kora (or ǃOra),2 in terms of its phonetics, morphology and lexis. (The use of the name Kora rather than ǃOra in an English medium context is explained in a note on nomenclature elsewhere in this introduction.) While the different dialects of Khoekhoe formerly spoken throughout much of South Africa are reported to have been more or less mutually intelligible, the differences between Kora and Nama involved far more than a mere question of ‘accent’ or minor aspects of local vocabulary, but extended to significant aspects of phonology, tonology, morphology, and syntax. -

An Overview Translation History South Africa 1652–1860

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE An Overview of Translation History in South Africa 1652–1860 By Birgitt Olsen A research report submitted to the Faculty of the Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts: Translation Adelaide, South Australia, 2008 i Abstract This research report comprises an outline of South African translation history in the years 1652 – 1860. The report is divided into three chapters, covering scriptural and secular translation history across two time periods, namely 1652-1750 (scriptural and secular), 1750-1860 (scriptural) and 1750-1860 (secular). A catalogue of translations done in these time periods is also included. The research methodology is based on hermeneutical principles, and therefore seeks to interpret and represent historical material in a way that makes it relevant for contemporary circumstances, always focusing on the individuals involved in events as well as taking into account the subjectivity of the researcher. In conclusion, but also as a part of the overall rationale for performing the research, the report discusses the immediate importance to modern society of understanding the historical linguistic dynamics between cultures, as represented in translation activity. ii Declaration I declare that this research report is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts: Translation, in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. ________________________________ Birgitt Olsen 20th day of November, 2008 iii Acknowledgements My sincere and warm thanks go to my supervisor, Dr Elizabeth Meintjes, for her perspicacious, patient and humorous assistance in the years it to me took complete this research report. -

The Khoisan Languages of Southern Africa: a Brief Introduction

Angola Botswana Zimbabwe Namibia South Africa The Khoisan languages of southern Africa: a brief introduction. Dr Menán du Plessis, Research Associate in the Dept of Linguistics, Stellenbosch University Program • Our eight workshops will cover general aspects of the typology of the three main families collectively referred to as southern African Khoisan. By the end of this short course, participants should have a good idea of the diversity of the languages commonly referred to under the umbrella term ‘Khoisan’. • The presentations will include copious amounts of data to illustrate aspects of the phonetics, morphology and syntax of these little-known and for the most part highly endangered African languages. Program • We will also touch on their present-day status and community efforts at conservation and revitalization. • We will note various controversial issues (theoretical linguistics) as well as some thorny topics in current documentary linguistics. • Lastly, and as a bonus, participants should by the end of the series be able to produce at least some of the clicks for which these languages are famous! Program Workshop 1 (Fri): Introduction Workshop 2 (Tues): KHOE – Khoekhoe Workshop 3 (Fri): KHOE – Kalahari Workshop 4 (Tues): JU (and ǂ’Amkoe?) Workshop 5 (Fri): TUU - Taa Workshop 6 (Tues): TUU – ǃUi NB: Assessment exercise should be manageable at this point. Workshop 7 (Fri): Current issues in documentary linguistics Workshop 8: Review. Course resources and evaluation • Resources (all available via Canvas) Handouts Readings* • Assessment (on Canvas) Data-based assignment * You may like to consult Rainer Vossen (ed.), The Khoesan Languages (Routledge, 2013). Workshop 1: Introduction • African context • Terminology and nomenclature • Distribution and status • Diversity of families • A few notes on tones, vowel features and clicks Africa: home to c. -

367 Trich Feathers, and Horns. Instead, the Areas North of Nǁuis Were Said

Who Were the Ancestors of the Namibian !Xoon? 367 trich feathers, and horns. Instead, the areas north of point worth consideration is that, also in the first Nǁuis were said to have been occupied by other San decade of the 20th century, the German colonial groups, namely Naro, Haiǁom, and Gainǂaman. The government run a model settlement scheme for few Taa speakers who nowadays live at the commu- Bushmen at Oas with the intention to slowly adapt nal area of Tjaka Ben Hur, which is located only a them to a sedentary lifestyle and farm labor (NAN few farms west of Tsachas, came there during the 1911–1913). However, old !Xoon claimed that they past four decades either together with their Tswana had nothing to do with that scheme and that they patrons or after a career as farm laborers in order only heard about Koukou (ǂKx‘au-ǁen) people be- to live with the relatives of their spouses. Several ing settled there while their own parents had kept reasons might account for the fact that Bleek met away from it out of fear (interviews with SM, JT, Taa speakers as far north as Tsachas and Uichenas. and JK, 06. 02. 2006 and 13. 02. 2006). This seems First, Tsachas is located on the Chapman’s River to be confirmed by Rudolf Pöch, who traveled in in the immediate neighborhood of Oas,9 an impor- Southern Africa between 1907 and 1909 and who tant station on the 19th-century trade routes from reported that two San groups were living at Oas: the south along the Nossob River and from the the Hei//um (Haiǁom), who spoke Nama, and the west coast through Gobabis to Lake Ngami in Bo- ǂAunin (ǂKx‘au-ǁen) who spoke their own language tswana. -

Oratures, Oral Histories, Origins

Trim: 152mm × 228mm Top: 10.544mm Gutter: 16.871mm CUUK1609-01 cuuk1609 ISBN: 978 0 521 19928 5 August 19, 2011 15:43 part i * ORATURES, ORAL HISTORIES, ORIGINS South Africa’s indigenous orature is marked, on one hand, by its longevity, since it includes the oral culture of hunter-gatherer societies now known collectively as the San; on the other hand it is marked by its modernity, because oral performance in South Africa is continually being reinvented in contemporary, media-saturated environments. This range is fully represented in the research collected in Part i, as is the linguistic and generic variety of the oral cultures of the region. These chapters bear out Liz Gunner’s observation about recent research in African orature in The Cambridge History of African and Caribbean Literature: the older model of freestanding oral genres, manifested in the often very fine collections of single or relatively few genres of ‘oral literature’ from a particular African society such as those published by the pathbreaking Oxford Library of African Literature series in the late 1960sandthe1970s...hasbeen superseded by theories of orality that embrace a far more interactive and interdependent sense of cultural practices and ‘text’. (F. Abiola Irele and S. Gikandi, eds., Cambridge University Press, 2004,p.11) The research collected here demonstrates this trend, with each chapter paying particular attention to the ways in which prevailing social, cultural, economic and political conditions have shaped the genres under discussion. Whilst the chapters are organised on a linguistic basis in an effort to cover all the major 15 Trim: 152mm × 228mm Top: 10.544mm Gutter: 16.871mm CUUK1609-01 cuuk1609 ISBN: 978 0 521 19928 5 August 19, 2011 15:43 Oratures, oral histories, origins indigenous languages of the region, the authors have been concerned to move awayfromnotionsoforalcultureastiedtofictionsofstableethnicidentities,or to an understanding of oral genres as being passed down from one generation to the next in a state relatively untouched by historical circumstance.