HUKOU) (1998-2004) February 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues for the 117Th Congress

Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues for the 117th Congress March 31, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46750 SUMMARY R46750 Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues March 31, 2021 for the 117th Congress Thomas Lum U.S. concern over human rights in China has been a central issue in U.S.-China relations, Specialist in Asian Affairs particularly since the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989. In recent years, human rights conditions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have deteriorated, while bilateral tensions related to trade Michael A. Weber and security have increased, possibly creating both constraints and opportunities for U.S. policy Analyst in Foreign Affairs on human rights. After consolidating power in 2013, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary and State President Xi Jinping intensified and expanded the reassertion of party control over society that began toward the end of the term of his predecessor, Hu Jintao. Since 2017, the government has enacted new laws that place further restrictions on civil society in the name of national security, authorize greater controls over minority and religious groups, and further constrain the freedoms of PRC citizens. Government methods of social and political control are evolving to include the widespread use of sophisticated surveillance and big data technologies. Arrests of human rights advocates and lawyers intensified in 2015, followed by party efforts to instill ideological conformity across various spheres of society. In 2016, President Xi launched a policy known as “Sinicization,” under which the government has taken additional measures to compel China’s religious practitioners and ethnic minorities to conform to Han Chinese culture, support China’s socialist system as defined by the Communist Party, abide by Communist Party policies, and reduce ethnic differences and foreign influences. -

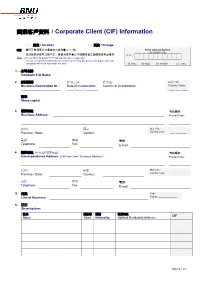

Customer Name

商業客戶資料 / Corporate Client (CIF) Information □ 開立 / Creation □ 更改 / Change 注意: - 請用正楷填寫並在適當的方格內劃上“”號。 PARA USO DO BANCO FOR BANK USE 如所提供作答的空間不足,請使用附有貴公司機構名稱之信函提供有關資料。 C.I.F.: Note : - Please fill in BLOCK LETTERS and tick where applicable In case the space provided for any answer is not enough, please use paper with your company letterhead to provide the data 日期 Date:___ (日 day) ____ (月 month) ______ (年 year) 1. – 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 2. 註冊號碼: 註冊日期: 註冊地: 國家代碼 Business Registration Nr. : Date of Incorporation: Country of Incorporation: Country Code: _______________________ ____ /____ / ________ ___ ___ ___ 資本: Share capital ____________________________ 3. 營業地址: 郵政編號: Business Address: Postal Code: 省/州: 國家 國家代碼 Province / State: Country: Country Code: ___ ___ ___ 電話: 傳真 電郵 Telephone Fax: E-mail: 4. 通訊地址: (若有異於營業地址) 郵政編號: Correspondence Address: (if different from “Business Address”) Postal Code: 省/州: 國家 國家代碼 Province / State: Country: Country Code: ___ ___ ___ 電話: 傳真 電郵 Telephone Fax: E-mail: 5. 行業: Code: Line of Business: Código ___________ 6. 股東 Shareholders 姓名: 持股權 國籍 常居地址: CIF Name: Share Nationality: Habitual Residential Address: Page 頁 1 of 4 7. 董事會成員及有效簽署人: Directors & Authorized Signatories: 姓名: 職位 國籍 常居地: CIF Name: /Title Nationality: Habitual Residential Address: 8. 持有其他公司股權 (如有) Shareholdings in other companies – if applicable 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 註冊地址 Registered Address: 註冊日期 持股金額 持股量 Date of incorporation Share Capital Capital _________________________________________________ ____ / ____ / _________ ___________________ _______ _________________________________________________ 公司名稱: Company Full Name: 註冊地址 Registered Address: 註冊日期 持股金額 所佔率% Date of incorporation Share Capital Capital _________________________________________________ ____ / ____ / _________ ___________________ _______ _________________________________________________ 9. 擁有之不動產(如有): Real Estate owned by the Company – if applicable 註冊地址: 地點: 市值: 負擔(抵押 / 按揭) Description/Registration details: Location: Value: Pledge / Mortgage: Page 頁 2 of 4 10. -

Immigration Manual

Immigration Manual November 2006 Baker & McKenzie International is a Swiss Verein with member law firms around the world. In accordance with the common terminology used in professional service organizations, reference to a “partner” means a person who is a partner, or equivalent, in such a law firm. Similarly, reference to an “office” means an office of any such law firm. © 2006 Baker & McKenzie All rights reserved. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study or research permitted under applicable copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or transmitted by any process or means without prior written permission. IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER. The material in this booklet is of the nature of general comment only. It is not offered as advice on any particular matter and should not be taken as such. The firm and the contributing authors expressly disclaim all liability to any person in respect of anything and in respect of the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done wholly or partly in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this booklet. No client or other reader should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any matter contained in it without taking specific professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances in issue. Immigration Manual Immigration Manual INTRODUCTION This manual is designed to provide a general overview of the immigration laws and procedures of various countries. Please note that the immigration laws and procedures are constantly changing and are subject to new policies and developments. Therefore, this manual is not intended to be exhaustive and specific questions should be directed to the Executive Transfer and Immigration Department of Baker & McKenzie, Hong Kong. -

China: Procedure and Requirements to Obtain a Biometric Passport

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 3 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. 6 May 2013 CHN104415.E China: Procedure and requirements to obtain a biometric passport, including date they started to be issued; indicators that the passport is biometric, including symbols Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Date of First Issue for Biometric Passports Sources indicate that China began to issue biometric passports on 15 May 2012 (China 16 May 2012; Dalian Municipal Government 17 May 2012). The identity-document checking service operated by Keesing Reference Systems writes that a passport that "contains a contactless chip in the back cover" was first issued in February 2012 (n.d.a). According to the official web portal of the Chinese government, traditional passports may continue to be used for as long as they are valid (China 16 May 2012). People's Daily Online, a Chinese news website founded in 1997 (People's Daily Online n.d.), reports that electronic passports for public affairs were first issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 1 July 2011 (5 July 2011). These passports contain a "'component layer,' consisting of microchips, electronic circuits, and other parts" inside the back cover, which includes "the passport owner's name, sex and personal photo as well as the passport's term of validity and [the] digital certificate of the chip" (ibid.). -

Copy of Cibtvisas Coronavirus Global Information.Xlsx

Travel Restrictions on China Coronavirus Outbreak The governments of China and additional countries have implemented restrictions to slow the spread of coronavirus including limitations on entry and exit, visa and work permit issuance, closed ports, tightened quarantine rules, and other rules. These restrictions may affect international business travel and assignment plans. The information displayed below is the most up‐to‐date that we have been able to gather from multiple sources around the world. Government responses, entry regulations, and quarantine rules may change at any time during this is a dynamic situation so please return to CIBTvisas.com for more information. If your destination is not listed below and you have been to China within the past 14 days or a country or a region affected by coronavirus you should expect additional questions upon entry, a medical evaluation, and may be denied entry. We strongly recommend that anyone who has traveled to China recently consult with their transportation provider (airline, cruise, etc.) to ensure that he or she will be permitted boarding and entry into their destination before departing. We will continue to update this document as we gather more information. Last Updated: February 10, 2020 ©2020 CIBTvisas, All Rights Reserved Last Updated: February 10, 2020 Page 1 cibtvisas.com/contact‐us Travel Restrictions on China Coronavirus Outbreak Countries/ Regions Travel Restrictions Afghanistan All travelers arriving from or having recently visited China will have their temperatures checked and may be subject to additional medical screening. Suspected cases will be quarantined. Chinese passport holders and recent travelers to China may be required to complete a health questionnaire and provide it upon arrival. -

Alien Resident Certificate (ARC) and Re-Entry Permit Application Process for International Students and Overseas Chinese Student

Alien Resident Certificate (ARC) and Re-entry Permit Application Process for International Students and Overseas Chinese Students (excluding students from Macau and Hong Kong) International students including Overseas Chinese Students are required to apply for ARC within 15 days upon arrival to Taiwan. Bring all the necessary documents to the National Immigration Agency in Kaohsiung City and apply for ARC. The ARC is valid for one (1) year. Students should apply for their ARC annually until they graduate. The re-entry permit is included in the ARC. Please remember to bring your valid ARC and passport when leaving or entering Taiwan. ARC Application Process: Before arrival Apply for resident visa After arrival Enroll to CSU Prepare necessary Get your ARC documents Apply for ARC Required documents (first time applicants): 1. Application form (Appendix 1: Sample of ARC Application Form for Foreigners) 2. Passport (original and copy) (valid for 6 months) 3. Visa (original and copy) 4. Letter of acceptance and letter of enrollment (original and copy) 5. Most recent 4.5cm X 3.5cm phot with white background 6. Proof of accommodation (or residential lease agreement) (original) 7. Application fees: International student: NTD 1,000; Overseas Chinese student: NTD 500 8. Other documents (e.g. proof of Taiwan scholarship, etc.) ※ PHOTO REQUIREMENT: The photo should be 4.5cm X 3.5cm with an image of the head that should not be shorter than 3.2cm or longer than 3.6cm from the top of the head to the chin, should not be wearing a hat or a pair of color glasses, with clear facial features not covered and identifiable, and should not be modified or composed. -

Criminal Background Check Procedures

Shaping the future of international education New Edition Criminal Background Check Procedures CIS in collaboration with other agencies has formed an International Task Force on Child Protection chaired by CIS Executive Director, Jane Larsson, in order to apply our collective resources, expertise, and partnerships to help international school communities address child protection challenges. Member Organisations of the Task Force: • Council of International Schools • Council of British International Schools • Academy of International School Heads • U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools • Association for the Advancement of International Education • International Schools Services • ECIS CIS is the leader in requiring police background check documentation for Educator and Leadership Candidates as part of the overall effort to ensure effective screening. Please obtain a current police background check from your current country of employment/residence as well as appropriate documentation from any previous country/countries in which you have worked. It is ultimately a school’s responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate police background documentation for their Educators and CIS is committed to supporting them in this endeavour. It is important to demonstrate a willingness and effort to meet the requirement and obtain all of the paperwork that is realistically possible. This document is the result of extensive research into governmental, law enforcement and embassy websites. We have tried to ensure where possible that the information has been obtained from official channels and to provide links to these sources. CIS requests your help in maintaining an accurate and useful resource; if you find any information to be incorrect or out of date, please contact us at: [email protected]. -

The Impact of Human Rights on Business Investors in China

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 14 Issue 1 Fall Fall 1993 Public Law, Private Actors: The mpI act of Human Rights on Business Investors in China Symposium: Doing Business in China Diane F. Orentlicher Timothy A. Gelatt Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Diane F. Orentlicher, Timothy A. Gelatt, Public Law, Private Actors: The mpI act of Human Rights on Business Investors in China Symposium: Doing Business in China, 14 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 66 (1993-1994) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Public Law, Private Actors: The Impact of Human Rights on Business Investors in China Diane F. Orentlicher* Timothy A. Gelatt** INTRODUCTION 1 The astonishing brutality of Beijing's clampdown on pro-democracy advocates near Tiananmen Square four years ago placed human rights in the forefront of U.S. policy concerns in the People's Republic of China (PRC). Perhaps inevitably, the debate over U.S. human rights policy toward Beijing has had a profound impact on the expanding web of trade and investment between the United States and China-itself a central concern of U.S. policy. The Tiananmen incident thus wove together two strands of U.S. policy toward the PRC that had previously been thought to be unrelated, raising a raft of complex policy dilemmas to which satis- factory solutions still remain to be fashioned. -

Chinese Diplomacy, Western Hypocrisy and the U.N. Human Rights Commission

March 1997 Vol. 9, No. 3 (C) CHINA Chinese Diplomacy, Western Hypocrisy and the U.N. Human Rights Commission I. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................2 II. THE EUROPEAN UNION AND THE UNITED STATES ..................................................................................4 III. LATIN AMERICA ...............................................................................................................................................5 IV. AFRICA ...............................................................................................................................................................7 V. CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE................................................................................................................9 VI. ASIA...................................................................................................................................................................11 VII. WAFFLING IN 1997 ........................................................................................................................................12 VIII. CONCLUSION................................................................................................................................................14 I. SUMMARY China appears to be on the verge of ensuring that no attempt is made ever again to censure its human rights practices at the United Nations. It is an extraordinary feat -

Smarter Aadhaar Card for a Smarter and Meticulous India

PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Smarter Aadhaar Card For A Smarter And Meticulous India Dr. Samson. R. Victor1, Candida Grace Dsilva N2, Pooja Tiwari 3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Education, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak (M.P.) India 2Teacher, National Public School, Bangalore, India 3Research Scholar, Department of Linguistics and Contrastive Study of Tribal Languages, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak (M.P.) India Email: [email protected], [email protected] ,[email protected] Dr. Samson. R. Victor, Candida Grace Dsilva N, Pooja Tiwari: Smarter Aadhaar Card For A Smarter And Meticulous India -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: India - Unique identification number, UIDAI, Aadhaar card & a smart card ABSTRACT The Unique Identification Number (UIDAI) – Aadhaar, is a unique number that is derived to identify every citizen of India, including the Non Residential Indians (NRI). This document was introduced to serve as an authentic identity proof for individuals. UIDAI is a secure document which consists of iris scan and fingerprint scan, that is person specific and identity theft is not very easy, making it a robust and versatile document.Exploring the robustness and versatility of this document this paper focuses on venturing out to identify the diverse applicability of the UIDAI to benefit both the government and the Indian citizens. In order to widen the scope of Aadhaar card, this paper proposes to use the Aadhaar card number to collect and store data such as demographic, health, education, employment, financial, police records of every resident of India so that the government can utilise the information, in order to monitor, analyse and frame policies and schemes in the field of education, employment,pension, scholarship, health schemes, dole, subsidiaries to farmers 10085 PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) and low income people,in order to up-lift the beneficiaries thus helping India to become a developed country. -

Guidebook for Entry for Training in Hong Kong

Immigration Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region ************************ Guidebook for Entry for Training in Hong Kong ID(E) 993 (5/2020) CONTENTS Paragraphs I. Introduction 1-2 II. Eligibility Criteria 3 III. Application Procedures 4-6 IV. Travel Documentation Requirement 7-8 V. Entry of Dependants 9-11 VI. Other Information 12-20 VII. Checklist of Forms and Documents to be Submitted I. Introduction This guidebook sets out the entry arrangements for persons who wish to enter the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) for training. 2. This entry arrangement does not apply to: (a) nationals of Afghanistan, Cuba, Laos, Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of) and Nepal; and (b) Chinese residents of the Mainland (other than Mainland employees and business associates of well-established and multi-national companies based in Hong Kong). II. Eligibility Criteria 3. An application for a visa/entry permit to enter the HKSAR for a limited period (not more than 12 months) of training to acquire special skills and knowledge not available in the applicant’s country/territory of domicile may be favourably considered if: (a) there is no security objection and no known record of serious crime in respect of the applicant; (b) the bona fides of the applicant and the sponsoring company are satisfied; (c) the sponsoring company is a well-established company, capable of providing the proposed training; (d) there is a contract signed between the sponsoring company and the applicant; (e) the sponsoring company guarantees in writing the maintenance and repatriation of the applicant and that the applicant will receive training in the sponsor’s premises until the end of the agreed period, after which the applicant will return to his/her place of residence; and (f) the proposed duration and content of the training programme can be justified.