Terrain Tribes and Terrorists: Pakistan, 2006-2008 (Extract from the Accidental Guerrilla, Chapter 4, Oxford University Press, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Db List for 04-02-2020(Tuesday)

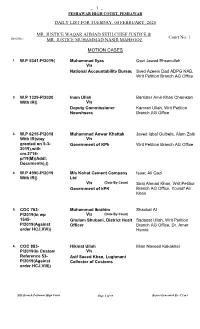

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE MUHAMMAD NASIR MAHFOOZ MOTION CASES 1. W.P 5341-P/2019() Muhammad Ilyas Qazi Jawad Ehsanullah V/s National Accountability Bureau Syed Azeem Dad ADPG NAB, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2. W.P 1329-P/2020 Inam Ullah Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani With IR() V/s Deputy Commissioner Kamran Ullah, Writ Petition Nowshsera Branch AG Office 3. W.P 6215-P/2018 Muhammad Anwar Khattak Javed Iqbal Gulbela, Alam Zaib With IR(stay V/s granted on 5-3- Government of KPk Writ Petition Branch AG Office 2019),with cm.2715- p/19(M)(Addl: Documents),() 4. W.P 4990-P/2019 M/s Kohat Cement Company Isaac Ali Qazi With IR() Ltd V/s (Date By Court) Siraj Ahmad Khan, Writ Petition Government of kPK Branch AG Office, Yousaf Ali Khan 5. COC 763- Muhammad Ibrahim Shaukat Ali P/2019(in wp V/s (Date By Court) 1545- Ghulam Shubani, District Health Sadaqat Ullah, Writ Petition P/2019(Against Officer Branch AG Office, Dr. Amer order HCJ,XVI)) Hamid 6. COC 883- Hikmat Ullah Mian Naveed Kakakhel P/2019(in Custom V/s Reference 53- Asif Saeed Khan, Lughmani P/2019(Against Collector of Customs order HCJ,VIII)) MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 88 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR TUESDAY, 04 FEBRUARY, 2020 MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. -

Dr Javed Iqbal Introduction IPRI Journal XI, No. 1 (Winter 2011): 77-95

An Overview of BritishIPRI JournalAdministrativeXI, no. Set-up 1 (Winter and Strategy 2011): 77-95 77 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH ADMINISTRATIVE SET-UP AND STRATEGY IN THE KHYBER 1849-1947 ∗ Dr Javed Iqbal Abstract British rule in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, particularly its effective control and administration in the tribal belt along the Pak-Afghan border, is a fascinating story of administrative genius and pragmatism of some of the finest British officers of the time. The unruly land that could not be conquered or permanently subjugated by warriors and conquerors like Alexander, Changez Khan and Nadir Shah, these men from Europe controlled and administered with unmatched efficiency. An overview of the British administrative set-up and strategy in Khyber Agency during the years 1849-1947 would help in assessing British strengths and weaknesses and give greater insight into their political and military strategy. The study of the colonial system in the tribal belt would be helpful for administrators and policy makers in Pakistan in making governance of the tribal areas more efficient and effective particularly at a turbulent time like the present. Introduction ome facts of history have been so romanticized that it would be hard to know fact from fiction. British advent into the Indo-Pakistan S subcontinent and their north-western expansion right up to the hard and inhospitable hills on the Western Frontier of Pakistan is a story that would look unbelievable today if one were to imagine the wildness of the territory in those times. The most fascinating aspect of the British rule in the Indian Subcontinent is their dealing with the fierce and warlike tribesmen of the northwest frontier and keeping their land under their effective control till the very end of their rule in India. -

Islam-2010/06/24 1

ISLAM-2010/06/24 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION JOURNEY INTO AMERICA: THE CHALLENGE OF ISLAM Washington, D.C. Thursday, June 24, 2010 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction and Moderator: STEPHEN GRAND Fellow and Director, U.S. Relations with the Islamic World The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: AKBAR AHMED Nonresident Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, American University Panelist: IMAM MOHAMED MAGID Vice President Islamic Society of North America * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 ISLAM-2010/06/24 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. GRAND: Welcome, everyone. We are very pleased that so many of you were able to join us today, for what I think is going to be a fascinating Journey into America, to paraphrase from the book, to quote from the book. And what I hope will also be a fascinating discussion here today. My name is Steve Grand. For those who don’t know me, I’m the director of the project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World here at Brookings, and it is our great honor, along with Brookings Press, to be able to hold this book launch even today for Professor Ahmed’s Journey into America. Copies of the book I should mention will be available for sale after this outside, and Professor Ahmed will be kind enough to sign books as people leave. This Journey into America that Professor Ahmed takes us through today, will take us through today and takes us through in his book, is really a sequel. -

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, Phd Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies School of International Service, American University

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed Curriculum Vitae Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, PhD Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies School of International Service, American University Address School of International Service, American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20016 Office: (202) 8851641/1961 Fax: (202) 8852494 EMail: [email protected] Education 2013 Honorary Doctorate, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan 2007 Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. 1994 Master of Arts, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 1978 Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, London, UK. 1965 Diploma Education, Selwyn College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (2 Distinctions). 1964 Bachelor of Social Sciences, Honors, Birmingham University, Birmingham, UK (Economics and Sociology). 1961 Bachelor of Arts, Punjab University, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan (Gold Medal: History and English). 195759 Senior Cambridge (1st Division, 4 Distinctions)/Higher Senior Cambridge (4 'A' levels, 2 Distinctions), Burn Hall, Abbottabad. Professional Career 2012 Diane Middlebrook and Carl Djerassi Visiting Professor, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Michaelmas Term). 2009 Distinguished Visiting Affiliate, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 1 Ambassador Akbar Ahmed Curriculum Vitae 20082009 First Distinguished Chair for Middle East/Islamic Studies, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 20062013 NonResident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC. 20052006 Visiting Fellow at Brookings Institution, Washington DC Principal Investigator for “Islam in the Age of Globalization”, a project supported by American University, The Brookings Institution, and The Pew Research Center. 2001 Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. -

Curriculum Vitae 1 Akbar Ahmed, Phd Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic

Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae Akbar Ahmed, PhD Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies School of International Service, American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20016 Office: (202) 885-1641/1961 Fax: (202) 885-2494 E-Mail: [email protected] Education 2007 Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. 1994 Master of Arts, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 1978 Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, London, UK. 1965 Diploma Education, Selwyn College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (2 Distinctions). 1964 Bachelor of Social Sciences, Honors, Birmingham University, Birmingham, UK (Economics and Sociology). 1961 Bachelor of Arts, Punjab University, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan (Gold Medal: First in History and English). 1957-59 Senior Cambridge (1st Division, 4 Distinctions)/Higher Senior Cambridge (4 'A' levels, 2 Distinctions), Burn Hall, Abbottabad. Professional Career 2012 Diane Middlebrook and Carl Djerassi Visiting Professor, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Michaelmas Term). 2009- Distinguished Visiting Affiliate, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2008-2009 First Distinguished Chair for Middle East/Islamic Studies, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2006- Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington DC. 2005-2006 Visiting Fellow at Brookings Institution, Washington DC -- Principal Investigator for “Islam in the Age of Globalization”, a project supported by American University, The Brookings Institution, and The Pew Research Center. 2001- Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. 1 Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae 2000-2001 Visiting Professor, Department of Anthropology, and Stewart Fellow of the Humanities Council at Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. -

2.5 Akbar Ahmed, Ibn Khaldun's Understanding of Civilizations And

Ibn Khaldun's Understanding of Civilizations and the Dilemmas of Islam and the West Today Author(s): Akbar Ahmed Source: Middle East Journal, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Winter, 2002), pp. 20-45 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4329719 Accessed: 07/02/2009 09:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mei. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal. http://www.jstor.org Ibn Khaldun'sUnderstanding of Civilizationsand the Dilemmasof Islamand the WestToday AkbarAhmed In the wakeof the September11 attacks,new attentionis beingpaid to bothsides of the debateover the competingideas of a "clashof civilizations"and thatof a "dialogueof civilizations;" in thisarticle, Ibn Khaldun's analysis of civilizations is examinedin the contextof the dilemmasfaced by Islam and the Westtoday. -

Genetic Analysis of the Major Tribes of Buner and Swabi Areas Through Dental Morphology and Dna Analysis

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS MUHAMMAD TARIQ DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA 2017 I HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA Department of Genetics GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS By Muhammad Tariq This research study has been conducted and reported as partial fulfillment of the requirements of PhD degree in Genetics awarded by Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Mansehra The Friday 17, February 2017 I ABSTRACT This dissertation is part of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) funded project, “Enthnogenetic elaboration of KP through Dental Morphology and DNA analysis”. This study focused on five major ethnic groups (Gujars, Jadoons, Syeds, Tanolis, and Yousafzais) of Buner and Swabi Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, through investigations of variations in morphological traits of the permanent tooth crown, and by molecular anthropology based on mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analyses. The frequencies of seven dental traits, of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) were scored as 17 tooth- trait combinations for each sample, encompassing a total sample size of 688 individuals. These data were compared to data collected in an identical fashion among samples of prehistoric inhabitants of the Indus Valley, southern Central Asia, and west-central peninsular India, as well as to samples of living members of ethnic groups from Abbottabad, Chitral, Haripur, and Mansehra Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and to samples of living members of ethnic groups residing in Gilgit-Baltistan. Similarities in dental trait frequencies were assessed with C.A.B. -

Taliban and Anti-Taliban

Taliban and Anti-Taliban Taliban and Anti-Taliban By Farhat Taj Taliban and Anti-Taliban, by Farhat Taj This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Farhat Taj All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2960-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2960-1 Dedicated to the People of FATA TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Preface........................................................................................................ xi A Note on Methodology...........................................................................xiii List of Abbreviations................................................................................. xv Chapter One................................................................................................. 1 Deconstructing Some Myths about FATA Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 Lashkars and Anti-Taliban Lashkars in Pakhtun Culture Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

A Case Study of the Bazaar Valley Expedition in Khyber Agency 1908

Journal of Law and Society Law College Vol. 40, No. 55 & 56 University of Peshawar January & July, 2010 issues THE BRITISH MILITARY EXPEDITIONS IN THE TRIBAL AREAS: A CASE STUDY OF THE BAZAAR VALLEY EXPEDITION IN KHYBER AGENCY 1908 Javed Iqbal*, Salman Bangash**1, Introduction In 1897, the British had to face a formidable rising on the North West Frontier, which they claim was mainly caused by the activities of ‘Mullahs of an extremely ignorant type’ who dominated the tribal belt, supported by many disciples who met at the country shrines and were centre to “all intrigues and evils”, inciting the tribesmen constantly against the British. This Uprising spread over the whole of the tribal belt and it also affected the Khyber Agency which was the nearest tribal agency to Peshawar and had great importance due to the location of the Khyber Pass which was the easiest and the shortest route to Afghanistan; a country that had a big role in shaping events in the tribal areas on the North Western Frontier of British Indian Empire. The Khyber Pass remained closed for traffic throughout the troubled years of 1897 and 1898. The Pass was reopened for caravan traffic on March 7, 1898 but the rising highlighted the importance of the Khyber Pass as the chief line of communication and trade route. The British realized that they had to give due consideration to the maintenance of the Khyber Pass for safe communication and trade in any future reconstruction of the Frontier policy. One important offshoot of the Frontier Uprising was the Tirah Valley expedition during which the British tried to punish those Afridi tribes who had been responsible for the mischief. -

The Other Battlefield Construction And

THE OTHER BATTLEFIELD – CONSTRUCTION AND REPRESENTATION OF THE PAKISTANI MILITARY ‘SELF’ IN THE FIELD OF MILITARY AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE PRODUCTION Inauguraldissertation an der Philosophisch-historischen Fakultät der Universität Bern zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde vorgelegt von Manuel Uebersax Promotionsdatum: 20.10.2017 eingereicht bei Prof. Dr. Reinhard Schulze, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Bern und Prof. Dr. Jamal Malik, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Erfurt Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Webserver der Universitätsbibliothek Bern Dieses Werk ist unter einem Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz Lizenzvertrag lizenziert. Um die Lizenz anzusehen, gehen Sie bitte zu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ oder schicken Sie einen Brief an Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. 1 Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Dokument steht unter einer Lizenz der Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ Sie dürfen: dieses Werk vervielfältigen, verbreiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen Zu den folgenden Bedingungen: Namensnennung. Sie müssen den Namen des Autors/Rechteinhabers in der von ihm festgelegten Weise nennen (wodurch aber nicht der Eindruck entstehen darf, Sie oder die Nutzung des Werkes durch Sie würden entlohnt). Keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Dieses Werk darf nicht für kommerzielle Zwecke verwendet werden. Keine Bearbeitung. Dieses Werk darf nicht bearbeitet oder in anderer Weise verändert werden. Im Falle einer Verbreitung müssen Sie anderen die Lizenzbedingungen, unter welche dieses Werk fällt, mitteilen. Jede der vorgenannten Bedingungen kann aufgehoben werden, sofern Sie die Einwilligung des Rechteinhabers dazu erhalten. Diese Lizenz lässt die Urheberpersönlichkeitsrechte nach Schweizer Recht unberührt. -

Islamist Militancy in the Pakistan-Afghanistan Border Region and U.S. Policy

= 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38 +,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= _=1&3=74389&)9= 5*(.&1.89=.3=4:9-=8.&3=++&.78= *33*9-=&9?2&3= 5*(.&1.89=.3=.))1*=&89*73=++&.78= 4;*2'*7=,+`=,**2= 43,7*88.43&1= *8*&7(-=*7;.(*= 18/1**= <<<_(78_,4;= -.10-= =*5479=+47=43,7*88 Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38+,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= = :22&7>= Increasing militant activity in western Pakistan poses three key national security threats: an increased potential for major attacks against the United States itself; a growing threat to Pakistani stability; and a hindrance of U.S. efforts to stabilize Afghanistan. This report will be updated as events warrant. A U.S.-Pakistan relationship marked by periods of both cooperation and discord was transformed by the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States and the ensuing enlistment of Pakistan as a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. Top U.S. officials have praised Pakistan for its ongoing cooperation, although long-held doubts exist about Islamabad’s commitment to some core U.S. interests. Pakistan is identified as a base for terrorist groups and their supporters operating in Kashmir, India, and Afghanistan. Since 2003, Pakistan’s army has conducted unprecedented and largely ineffectual counterterrorism operations in the country’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) bordering Afghanistan, where Al Qaeda operatives and pro-Taliban insurgents are said to enjoy “safe haven.” Militant groups have only grown stronger and more aggressive in 2008.